Last week we discussed how Baptist and Bootlegger coalitions have taken the wind out of the sails of the charter school movement. The term “Baptists and Bootleggers” comes from regulatory economics and in the context of charter schools describes how elements of the charter school movement (in this case large CMOs) have effectively partnered with the anti-charter usual suspects to limit competition-900 page applications, charter laws hewing closely to sponsored “model” bills but mysteriously producing few charter schools, etc.

Private choice laws are not immune to this danger. The most obvious path involves requiring accredited private schools.

For example, Oklahoma lawmakers recently passed by far the most robust personal use tax credit policy in the nation. All previous programs of this type pale by comparison, and thus is both a highly laudable move that will provide opportunities for thousands of Oklahoma families. The law however reserves the large credit for tuition and fees at accredited private schools, and Oklahoma has a limited supply of such schools.

An Oklahoma parent wishing to use the credit must find a seat at an accredited private school with seats available in their grade level appropriate for their child. The universe of accredited private schools however is limited- perhaps an eighth of the size numerically of the 1,700 public schools in Oklahoma.

The current stock of private schools in Oklahoma will only go so far in creating a demand driven K-12 system, which will require the onboarding of new private school seats if demanded. Oklahoma has a commission focused on private school accreditation, and snooping around various approved accreditation websites makes accreditation sound like a multi-year process.

Until a school receives accreditation, they will be in competition with schools whose students can receive credits. I have no idea whether lawmakers included this provision at the behest of incumbent accredited private schools, but you do not need a graduate degree in political science to figure out who might lobby against changing this rule (both Baptists and Bootleggers). Fortunately, this Baptist and Bootlegger adjacent provision has straightforward fixes, such as including schools in the process of seeking accreditation, or (better yet) eliminating the accreditation provision entirely.

A great many teachers have had it with administration and bureaucracy and yearn to run a school of their own. Our policies must avoid anti-competitive provisions if we are going to give them the opportunity they deserve. Bootlegger provisions, including provisions that require accredited schools, or require ESA families to spend money at private schools before anything else, should be held in suspicion.

As late as the early 1990s, many Americans thought of going to see European films as desirably highbrow. European movies commanded 10% of the American box office. The problem with this was that European governments subsidized cinema, and the results were, well, uneven.

I recall going to see such a film titled “King Lear” as a university student only to be greeted by an old man sitting on a beach with the sounds of the waves coming ashore and (maybe?) someone whispering Shakespeare in the background. I decided that I had better ways to spend my cultural dollars, and so did many of my fellow Americans. European film viewership in the USA collapsed a few years later. Needless to say, there have been many fantastic European films, but the life lesson for me: never assume that the adjective European is a synonym for optimal.

All of which is prologue to the topic at hand, which is an opinion piece by Patrick T. Brown that effusively praises the European model of choice (whereby there is some but in which everyone must follow national academic standards and give national tests). Brown sums up his piece:

The parents’ rights and school choice movements aim to improve students’ academic, social and moral formation. That won’t automatically follow from a few policy wins. The new landscape for K-12 education will require the kind of studied, technocratic approach that doesn’t necessarily garner applause on a debate stage but is essential to making the permanent and lasting change conservatives would like to see.

A “studied, technocratic approach” is what we (allegedly) receive in American school districts. Democratically elected boards hire “expert” superintendents, principals and (usually) “certified” teachers. Sadly, we awake every day from our technocratic dream to a reality of widespread illiteracy, civic ignorance and philosopher-kings coronated by regulatory capture. If a “studied, technocratic approach” were the solution to our K-12 problems, we wouldn’t have them.

Over the years, school choice advocates have learned the hard way what not to do, or have we? Louisiana, for instance, enacted a heavily regulated school voucher program in 2008 that places onerous admission and curriculum restrictions on participating private schools, as well as a requirement to administer the state annual assessment. Accordingly, most of the state’s private schools chose not to participate, and many that did participate had falling enrollments before the advent of the program. When scholars published an academic evaluation of the Louisiana program, it was the first program to show negative results.

A basic flaw of technocracy is that the proponents imagine virtuous rule by disinterested philosopher-kings, but we wind up with politicized messes. For instance, we have witnessed a decline in the American charter school movement wherein incumbent operators team with charter opponents to throttle charter school growth. The proponents claimed that they were ensuring “quality,” but the correlation between technocracy and a vanishingly small number of charter seats is strong, quality non-existent.

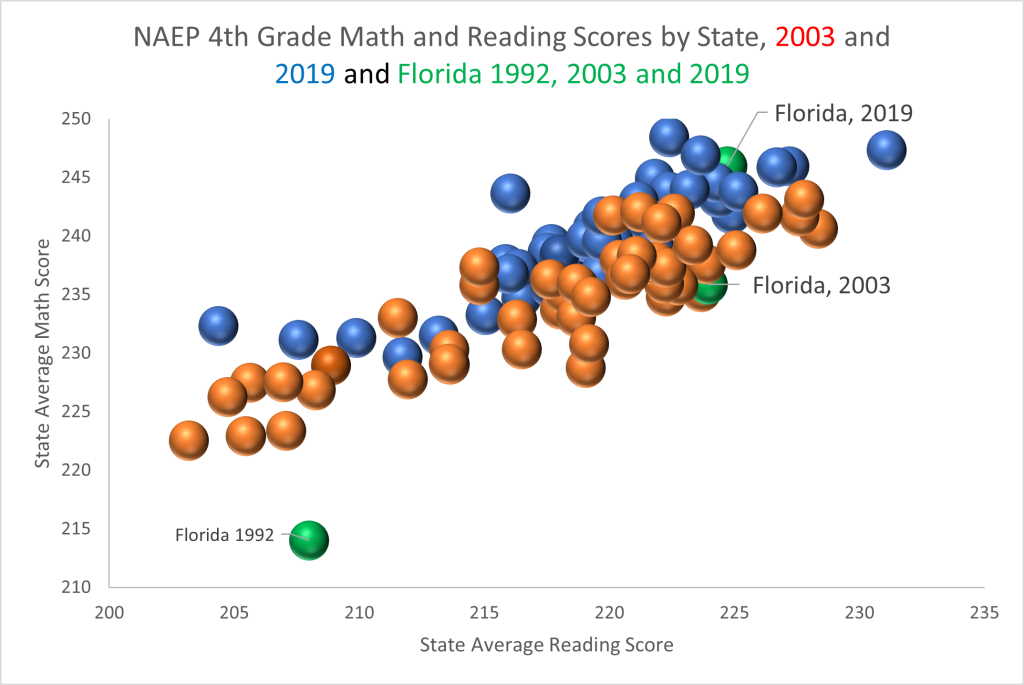

Finally, we have home-grown in the USA examples of choice programs delightfully free of European-style technocracy spurring broad academic improvement. Florida began private choice programs in 1999. Florida choice programs have a testing provision but allow schools to choose from a menu of assessments. This helps ensure a much higher private school participation rate than in Louisiana, which mandated the state test. It also ensures a greater diversity of schools.

Henry Ford once quipped that buyers could have a Model T in any color they liked, as long as it was black. Florida has had no need to offer assistance for families to choose any school they want, as long as they follow state academic standards and tests.

As Douglas Carswell (a wise European) wrote in The End of Politics “The elite gets things wrong because they endlessly seek to govern by design in a world that is best organized spontaneously from below. They constantly underrate the merits of spontaneous, organic arrangement, and fail to recognize that the best plan is often not to have one.” We should view European pluralism as an undesired floor rather than the highest possible ceiling.

Sarrin Warfield received a “flurry” of information from her local district school over the summer on whether her child’s classes would be in-person or online. She was concerned about her daughter, Emerson, “sitting in front of a computer from 7:45 a.m. to 2 p.m., which we’ve really been intentional to not have that be her life,” Warfield said.

Sarrin Warfield received a “flurry” of information from her local district school over the summer on whether her child’s classes would be in-person or online. She was concerned about her daughter, Emerson, “sitting in front of a computer from 7:45 a.m. to 2 p.m., which we’ve really been intentional to not have that be her life,” Warfield said.

Warfield chose to create a learning pod with a group of friends in South Carolina. Instead of seeing a learning pod as a “crazy idea,” Warfield said, she and her friends poured their nervous energy over school re-openings into being “really intentional about doing this and making it happen.”

“We’ve all committed,” Warfield said, and “we’re in it to win it.”

But just as parents like Warfield embarked on this new initiative to continue their children’s education as local schools closed to in-person learning, state regulators began to issue warnings that certain requirements could apply to learning pods. In a new report for the State Policy Network, I explain that some state and even local officials may require families participating in parent-led learning pods to obtain in-home child care licenses or be subject to other child care-related rules such as zoning laws or specific adult-child ratios.

Learning pods are like micro-schools, but micro-school students usually attend private schools (though some micro-schools partner with traditional and charter public schools). Microschool operators such as Acton Academy, based in Texas, establish these small schools in different locations as private schools and charge tuition. Still, Prenda microschool founder Kelly Smith says microschools are “variations on a theme” from each other.

In terms of new regulations, then, the differences between micro-schools and pods and between one micro-school organization and another matter less than the overlapping features, which means new rules should be a concern for families involved with either innovative solution.

The new rules for pods vary from state to state, but regulations or threats of future rule enforcement can be found across the country.

In Maine, the Office of Child and Family services said families that want to form a learning pod to participate in public school e-learning activities may have to acquire a childcare license. If, for example, “instruction and supervision are compensated,” this will require a license if the children are enrolled in a public school.

State officials are not the only policymakers issuing rules.

In Broward County, Florida, district administrators say pods may be operating illegally if they have not been licensed as either a daycare or a private school. In Austin, Texas, city officials say anyone “hosting a pod [must] have a detailed health and safety plan,” including rules for handling everything from “outdoor time” and transportation to meals and snacks. Families hosting pods in their home must get permission from state officials.

Many childcare regulations have little to do with child safety. These rules limit the supply of center-based care and the creation of in-home care arrangements because caretakers find it difficult to obtain the necessary approvals. If these same rules are applied to learning pods, families should expect the same stifling effects.

As I explained in a September post for this blog, most state lawmakers are not in session now, which means legislative answers to state agency overreach may not arrive until next year. Lawmakers should prepare to consider proposals that align learning pods with existing homeschool and private school laws so that pod families do not bear heavier regulatory burdens than families that have made other education choices for their children.

Such support will be crucial because as the Wall Street Journal reported in October, teacher unions are looking for ways to undermine microschools, creating yet another challenge for families and entrepreneurs trying to help students succeed when district e-learning platforms fall short.

Warfield’s learning pod has been exactly what she and Emerson needed this fall. She reports: “Families giving themselves permission to do what is best for our families is the ultimate.”

As she and other pod and microschool families make education a priority, public officials should move regulations out of the way.