The future of education is happening now. In Florida. And public school districts are pushing into new frontiers by making it possible for all students, including those on education choice scholarships, to access the best they have to offer on a part-time basis.

That was the message Keith Jacobs, director of provider development at Step Up For Students, delivered on Excel in Education’s “Policy Changes Lives” podcast A former public school teacher and administrator, Jacobs has spent the past year helping school districts expand learning options for students who receive funding through education savings accounts. These accounts allow parents to use funds for tuition, curriculum, therapies, and other pre-approved educational expenses. That includes services by approved district and charter schools.

“So, what makes Florida so unique is that we have done something that five, 10, even, you know, further down the line, 20 years ago, you would have never thought would have happened,” Jacobs said during a discussion with podcast host Ben DeGrow.

Jacobs explained how the process works:

“I’m a home education student and I want to be an engineer, and the high school up the street has a remarkable engineering professor. I can contract with the school district and pay out of my education savings account for that engineering course at that school.

“It’s something that was in theory for so long, but now it’s in practice here in Florida.”

It is also becoming more widespread in an environment supercharged by the passage of House Bill 1 in 2023, which made all K-12 students in Florida eligible for education choice scholarships regardless of family income. According to Jacobs, more than 50% of the state’s 67 school districts, including Miami-Dade, Orange, Hillsborough and Duval, are either already approved or have applied to be contracted providers.

That’s a welcome addition in Florida, where more than 500,000 students are using state K-12 scholarship programs and 51% of all students are using some form of choice.

Jacobs said district leaders’ questions have centered on the logistics of participating, such as how the funding process works, how to document attendance and handle grades.

Once the basics are established, Jacobs wants to help districts find ways to remove barriers to part-time students’ participation. Those could include offering courses outside of the traditional school day or setting up classes that serve only those students.

Jacobs said he expects demand for public school services to grow as Florida families look for more ways to customize their children’s education. That will lead to more opportunities for public schools to benefit and change the narrative that education is an adversarial, zero-sum game to one where everyone wins.

“So, basically, the money is following the child and not funding a specific system. So, when you shift that narrative from ‘you're losing public school kids’ to ‘families are empowered to use their money for public school services,’ it really shifts that narrative on what's happening here, specifically in Florida.”

Jacobs expects other states to emulate Florida as their own programs and the newly passed federal tax credit program give families more money to spend on customized learning. He foresees greater freedom for teachers to become entrepreneurs and districts to become even more innovative.

“There is a nationwide appetite for education choice and families right now…We have over 18 states who have adopted some form of education savings accounts in their state. So, the message to states outside of Florida is to listen to what the demands of families are.”

Since 2016, Lizette Gonzalez Reynolds has served as vice president of policy for ExcelinEd, launched in 2008 by former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush to pursue education policies for improving student learning and lessening inequities.

Editor’s note: This article appeared Monday on tn.chalkbeat.org.

Penny Schwinn will step down as Tennessee’s education chief at the end of this school year and be replaced by a former Texas administrator who currently oversees policy for the Jeb Bush-founded advocacy group ExcelinEd.

Lizzette Gonzalez Reynolds will become the first Hispanic American to lead Tennessee’s education department when she starts her job on July 1.

Meanwhile, Schwinn told reporters Monday that she plans to continue living in Tennessee and will share her next venture at a later date.

“It’s just the right time for me and my family,” said Schwinn, a mother of three young children, about leaving after more than four years as education commissioner.

The changes, announced Monday by Gov. Bill Lee, come at a critical time for the state’s 1 million public school students and just a few months into the second term of an administration that has been one of the most active in history on changing education policies.

Tennessee is shifting to a new education funding formula, enforcing a controversial new third-grade retention policy for struggling readers, operating large-scale tutoring and summer learning programs to help students catch up from the pandemic, expanding its private school voucher program to a third major city, and fortifying its school buildings after a Nashville school shooting left six people dead on March 27. Replenishing Tennessee’s teacher supply is also a priority.

In Reynolds, Lee has chosen a leader who is heavy on political and policy experience but who has little to no experience leading a classroom. In conjunction with her appointment, she will actively work toward her Tennessee teaching license.

“The governor has full confidence in her ability to serve Tennessee students, families, and teachers,” said Jade Byers, Lee’s spokeswoman.

Reynolds graduated in 1987 with a political science degree from Southwestern University in Georgetown, Texas, before embarking on nearly three decades of policy and legislative work in education at the state and federal levels.

To continue reading, click here.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Ben DeGrow, policy director of education choice at ExcelinEd, appeared Thursday on the ExcelinEd website.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Ben DeGrow, policy director of education choice at ExcelinEd, appeared Thursday on the ExcelinEd website.

Last month, the nation took notice as Florida fully opened the doors of education freedom to K-12 students in the Sunshine State by making all families eligible for an education scholarship account.

On July 1, Florida is set to become the third state in the nation to launch an ESA program with universal eligibility.

Budget negotiations, now underway, will determine the number of scholarships available in the upcoming school year. In recognizing program dollars would be limited, policymakers also ensured that the new law guarantees students from households at the lower end of the spectrum are near the front of the line.

An additional feature of the Sunshine State’s enhanced ESA program will soon benefit many families that receive a scholarship: choice navigation. Florida parents will have the option to use some of their ESA funds for a credentialed consultant, known as a choice navigator, who can help them choose the most effective curricula, academic programming or support services for their child.

Similarly, the state’s education department has been charged with developing an online portal that will be able to recommend specific schools and other resources based on a student’s needs and interests.

The wealth of options unlocked by ESAs can be a huge benefit. Yet a quick look at other states suggests this also can be overwhelming. Arizona’s universal ESA program has approved nearly 3,000 different service providers that parents can select from on the state’s digital direct pay platform. More than 1,000 options are for tutors alone.

In New Hampshire, the state’s Education Freedom Accounts—after less than two years in operation—enable participating families to use their funds at any of more than 650 schools, tutors, therapists, educational programs and retail vendors.

In some states, nonprofit organizations fill the valuable role of informing parents about their options in various school choice programs. Parents for Educational Freedom in North Carolina operates a website that lets users search and compare different kinds of schools. In Texas, Families Empowered is assisting parents of special-needs students who receive a $1,500 microgrant.

There’s also a private initiative created by the founders of the online course platform Outschool. The company’s nonprofit arm is focused on helping low-income and minority families navigate the nontraditional path of customized learning through an innovative approach called Outbridge.

In a partnership with the Engaged Detroit homeschool co-op, Outbridge provides a menu of community-based and virtual learning options for parents to purchase with pre-authorized debit cards. Early results show parents have diverse spending habits, but they tend to favor known local resources over remotely accessed providers.

With on-the-ground partner AmplifyGR, Outbridge has launched a parallel project in Grand Rapids, Michigan, for parents of district and charter school students to identify and purchase supplemental services.

In both of these communities, trained coaches also help to give further guidance to parents who struggle with their decisions. This has proven especially helpful to those long accustomed to having limited resources for their children. Outbridge has seen more parents make spending decisions immediately after holding in-person community events designed to provide more hands-on information.

Florida’s program administrators and prospective navigators may learn some helpful lessons from these pilot efforts to benefit families. Meanwhile, leaders in other states with expansive choice could embrace this kind of assistance as a priority. That’s one way to help ensure the promise of universal ESAs doesn’t leave anyone behind.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Patricia Levesque, chief executive officer for ExcelinEd, appeared recently on the ExcelinEd website.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Patricia Levesque, chief executive officer for ExcelinEd, appeared recently on the ExcelinEd website.

In the span of just a few years, more than a dozen states have gone from nibbling at the edges of school choice to a full-throated embrace of universal education scholarship accounts or targeted ESA programs. These life-changing opportunities offer families the ability to customize a child’s education in ways we policy wonks could only dream of when the parental choice movement first began to take shape decades ago.

With unencumbered choice policy sweeping the nation, there’s no turning back: Families who have access to K-12 options will not have to accept a school that’s assigned to them based on where they live.

For those new to the most flexible form of school choice: Universal ESAs empower parents to pay for myriad educational expenses, including tuition, textbooks, therapies, exam fees, technology and other educational materials.

Universal choice means students can attend a private school, supplement their education with tutoring or technology, participate in a home education program or enroll in public school part-time to access their courses of choice. Unlike traditional voucher programs—which historically were designed to serve low-income families, students with special needs or families with children in failing schools—universal choice programs, including ESAs, are available to all families, regardless of income or school district.

But as we know from states like Florida, Arizona and Indiana, where public and private school choice have been the law of the land for some time, passing a program is just the beginning. I was pleased to recently join advocates from those states for a podcast exploring what comes next for states as they set up their educational choice programs.

The answer is simple: Implementation is everything, and implementation is so much more than setting up an initial framework.

For parents to use ESAs effectively, they must first know that the program exists. There also must be a clear and streamlined process for setting up the scholarship accounts, a user-friendly approach for managing funds and a comprehensive list of eligible schools and providers from which parents can choose.

And beyond these basics, lawmakers and public officials in states that have universal ESAs will likely need to tackle several big policy issues as their implementation of universal school choice moves forward:

SUFFICIENT FUNDING FOR ALL ESA STUDENTS: Is there sufficient funding for the program, especially when it comes to funding that follows low-income students, students with special needs and other at-risk students?

FUNDING AT ALL LEVELS OF GOVERNMENT: Is local funding, not just state funding, following the student? States may need to make up for the local share or require local funds to follow the student to make that student financially whole.

TRANSPORTATION: Are parents able to access the educational options that work best for their children? The physical act of getting to a provider can be an enormous barrier for many families.

PRIVATE SCHOOL SUPPLY: We know that parent demand is growing for private and nontraditional schooling, but in many states the supply side is not keeping up. States might need to consider some supports similar to those created in the charter school space, such as revolving loan funds for school construction, low-interest state-supported financing and access to unused public school facilities.

LOCAL INTERFERENCE: Whenever choice expands, those who wish to maintain the status quo react. Opponents are finding less success with traditional legal challenges lately, as courts continue to find in favor of school choice programs. So, choice opponents are getting creative and turning to the local level, where interference can be less obvious, such as misuse or modification of zoning policy or health code provisions to prevent providers from serving families. States need to be on the lookout for attempts to thwart choice using local rules that were never intended to apply to K-12 education.

NAVIGATING CHOICE: States like Florida are thinking ahead to provide parents, especially low-income families, with navigation services to help them figure out how a program works so they can obtain the outcomes they seek for their children.

The passage of universal ESA programs across the nation means millions more students will be able to access customized learning options. However, in order for these programs to be as effective as possible, policymakers must continue to ensure seamless and smooth implementation that centers on parents, educators and service providers and allows for continued refinement as the program matures.

Editor’s note: This commentary from former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush appeared Friday on wsj.com.

Editor’s note: This commentary from former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush appeared Friday on wsj.com.

It shouldn’t surprise anyone: I’m a proud Floridian.

It’s the state I’ve long called home, where I raised my family and gratefully served two terms as governor. It’s also why I’m proud to boast about a new bill introduced by the Florida legislature to scale and improve school choice in the Sunshine State.

Last month, Speaker Paul Renner introduced House Bill 1, which will make Florida’s school choice program the most expansive, inclusive and dynamic in the country and will accelerate Florida’s leadership in reimagining education.

Since I signed Florida’s first statewide school choice bill into law 25 years ago, we’ve largely led the nation in education freedom. Since then, 31 states, as well as Washington and Puerto Rico, have enacted school choice policies, dramatically expanding the power of parents to exercise control over how their child’s education is provided.

Yet despite having the nation’s largest school choice program, we are beginning to trail other states in offering the most innovative solutions to students.

First, Arizona and West Virginia started nipping at Florida’s heels. Even as Florida made important improvements and expansions to its programs, both of these states enacted universal education savings account programs, or ESAs, surpassing Florida’s reach by delivering educational freedom to all families.

ESAs are a game changer. They empower families to personalize their children’s education. Want to purchase an online math course? ESAs cover that. Extra books? ESAs allow for that. Tutoring to close learning gaps? That’s an allowable ESA expense. Maybe your student needs a blended approach that includes private school tuition and educational therapies. An ESA has your back.

With these flexible and powerful accounts, education dollars are no longer exclusively used to fund systems. Instead, ESAs enable education funding to focus on helping to individualize each student’s learning experience, giving every child his best shot at a great education and lifelong success.

There’s a bona fide movement for educational choice and flexibility sweeping the nation. On Jan. 24, Iowa Gov. Kim Reynolds signed the Students First Act into law, making Iowa the first state this year to enact a school choice bill and becoming the third state in the nation to provide universal ESAs to families.

And only a few days later, on Jan. 28, Utah Gov. Spencer Cox signed school choice legislation into law. All told, bills to establish universal choice are moving in more than a dozen states, including Indiana, Ohio, New Hampshire, Texas and Virginia.

In Arkansas and Nevada, newly elected governors Sarah Sanders and Joe Lombardo have spoken boldly about ensuring their respective states will soon offer or expand school choice.

Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt and newly elected State Superintendent Ryan Walters are committed to creating a universal ESA program for Sooner State families. In South Carolina, Gov. Henry McMaster and newly elected State Superintendent Ellen Weaver have committed to fighting to expand educational opportunity.

With the right leadership, a 21st-century vision and the resolve to put families first, these states in all parts of the nation are moving this student-centered movement into high gear. Even before the pandemic, parents were demanding more autonomy and greater control over their children’s education.

The pandemic accelerated that by shining a light on deficiencies in our education systems. A February 2022 Real Clear Opinion Research poll found that more than 72% of parents supported school choice, including 68% of Democrats, 82% of Republicans and 67% of independents.

Educational choice is popular and empowering parents is the right thing to do. Pennsylvania’s newly elected Democratic Gov. Josh Shapiro has said that traditional public schools can be funded alongside school choice. And he’s right.

Nearly 200 years ago, when the industrialized school system we know today first emerged, it made sense to build massive schools that focused more on “averages” than individuals. For its time, assembly-line education mirrored the successful assembly lines of the unfolding industrial age. And aside from a few private schools, there weren’t many available alternatives.

Today, the U.S. economy is far more advanced, and new options for education abound. So rather than accepting an education system designed to teach to the average, parents are rightfully demanding a system that is individualized and empowers each student to achieve his full potential.

For too long, public-education funding has worked primarily for the special interests that run school systems for their own benefit. Florida’s HB1 is a game changer. Not only will it create the nation’s largest ESA program, it will supercharge flexibility.

Best of all, this student-centered movement is the product of competition among states, free from the grips of special interests, bureaucrats and top-down federal mandates.

This benefits everyone by finally making public education work for the students and families it exists to serve.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Patricia Levesque, chief executive officer for the Foundation for Excellence in Education and former deputy chief of staff for education for Florida Gov. Jeb Bush, appears in the summer issue of Education Next.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Patricia Levesque, chief executive officer for the Foundation for Excellence in Education and former deputy chief of staff for education for Florida Gov. Jeb Bush, appears in the summer issue of Education Next.

There’s a fierce determination among elected officials and education leaders to return our schools to normal. That’s understandable, but the desire for normalcy must not compel us to settle for an education system that was struggling long before the pandemic turned “normal” on its ear.

Right now, parents have a unique and unprecedented opportunity: To emerge from this pandemic with a transformed education system, one that offers more options to families and embraces new policies that build toward reimagining the entire system. It’s incumbent on education advocates, each and every one of us, to harness the energy, frustration and needs of families to create this better education system.

Success requires eliminating the conventional “us versus them” mindset. That friction is often on display between those seeking a student-centered system and advocates of the current system, but there’s often infighting among education reformers themselves. Proponents are criticized for being either too focused on incrementalism or thinking too big picture; too intent on reshaping existing systems or too committed to overhauling everything.

Disagreements can also devolve into reformers moving into camps, rallying around their one best approach. That’s absurd because there’s no such thing. The future of education requires a diversity of thought, as well as a diversity of approaches.

That’s why I see the education work ahead of us focused on three areas, which can truly transform education from system-centered to student-centered.

To continue reading, click here.

Ben DeGrow, new policy director for education choice at ExcelinEd, is pictured with his wife, Marya, who he met at a College Republicans meeting while attending Hillsdale College, and the couple’s three daughters. PHOTO: Mackinac Center for Public Policy

After working for nearly two decades in state-based public policy providing expert analysis in school choice, school finance and more, Ben DeGrow has accepted the position of policy director, education choice, at ExcelinEd. During his tenure at Michigan’s Mackinac Center for Public Policy and Colorado’s Independence Institute, DeGrow led dozens of studies and research project initiatives while managing and supporting coalitions to advance student opportunity through greater parental choice.

A summa cum laude graduate of Hillsdale College, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in history, and The Pennsylvania State University, where he received a master’s degree in history, DeGrow’s classroom experience includes graduate assistance and substitute teaching in public elementary and middle schools in Michigan.

DeGrow spoke with reimaginED recently about how his experience leading state-based initiatives has prepared him to enter the national arena of education choice at ExcelinEd.

Ben DeGrow

reimaginED: In addition to being a policy expert, you’ve spent time in the classroom, both as a university graduate assistant and as a substitute teacher in Michigan public schools. Were your early ambitions to be a classroom teacher?

DeGrow: My early interest and love of history, and particularly American history, convinced me that I would like to be a college professor in that field. When I was a senior in college, I asked five professors what they thought of my academic ambitions. Four out of five basically told me, “You don’t want to do this, this job market is very challenging.” That wasn’t enough to deter me. I went to graduate school and served as an assistant for general requirement classes for undergraduate students. I got to see the less glamorous parts of teaching, like grading blue book exams, as well as the more enjoyable things like leading student discussions.

After deciding to get a terminal master’s degree instead of a Ph.D., I thought the next best thing I could do was teach high school history. I quickly realized it was not my calling. Then when I found the world of public policy, I realized that was a place where I could better put my talents to work.

I worked as a substitute teacher between teaching university students and high school students. That was an experience that allowed me to teach in a rural setting and experience the challenges of classroom management and learn what kinds of issues teachers face at the ground level. That experience is something I always keep in mind as I research and write. I try to think in terms of policies that are designed to help meet a student’s individual needs. To be most effective in public policy, you have to have an understanding of the different aspects of the education system and how it operates.

reimaginED: Before joining the Mackinac Center, you provided analysis on school choice, school finance, collective bargaining and education employment policies at Colorado’s Independence Institute. How did your work there prepare you for what was to come next?

DeGrow: I got on board at the institute because my wife worked there part time. I knew the people at the institute, and when they needed a research project exploring some education topics, I signed on because I had the training from grad school to know how to do research. From my education experience, my research background, I loved the opportunity to explore public policy and have an impact.

I just continued to develop that expertise over time. I learned more from every opportunity and challenge that came along. I had the chance to read, research, speak, and to better understand how the system works. I did that work in Colorado for about 12 years, and over that time we did everything from highlighting innovative school district models to addressing issues related to improved school funding systems, and then working with local school board reformers on ambitious projects to provide greater education choice.

All of that played a role as I moved from Colorado to Michigan, which proved to be a more challenging environment when it comes to education choice. I think it all helped prepare me to do policy work at the Mackinac Center and make an impact on some key challenges there.

reimaginED: What was your role at the Mackinac Center, and of what project launched during your tenure there are you most proud?

DeGrow: In my six years on the great team at the Mackinac Center, I valued the opportunity I had to visit and meet with charter school leaders, to observe them in action and be able to be a voice, an informed voice, that could call on the research, that first-hand experience, and point out that the partisan political attacks against them were unfounded. I was happy when we were able to fend off attacks on parent options at public charter schools.

I was also appreciated getting to participate in a project we called the context and performance report card. That provided another lens to assess how well schools were performing by capturing multiple years of test data and adjusting the data based on the number of students in poverty. I had the chance to visit schools that were beating the odds, some charter schools, some traditional district schools, that were working in either challenging urban or rural environments.

But I would say the capstone, the most important thing I participated in was the work to give Michigan families a breakthrough of education options through Let Kids Learn. We heard the frustrations of parents during COVID, many of whom had taken their children’s schooling experience for granted, and then realized they had at their disposal the chance to push for big policy changes that could help them. I believe the Mackinac Center and our partners were able to make a great deal of progress in raising the profile of Michigan as a place where education choice could grow and flourish to help children and families. Even though it’s not reached the finish line yet, we made a great deal of progress.

reimaginED: What would you cite as a big takeaway from your work at the Mackinac Center?

DeGrow: I think that sometimes we tend to think once a major law is passed, the work is done. You wipe off your hands and move to the next thing. But even then, there are legal battles still to fight to preserve school choice programs, not to mention the challenges with implementation. That is important and challenging work that needs and deserves attention as well. I think Florida is an example of that. You have one of the preeminent private school programs in the country, and yet parents and supporters have had to defend it over and over. Reform is work that’s never finished, as Gov. Bush would say. There is always more to be done to ensure that students have the educational opportunities they deserve.

reimaginED: You’ve appeared before legislative committees in recent years in connection with your school choice work. What do you think you brought to those proceedings, and did you feel your testimony was fruitful?

DeGrow: I’ve testified on a lot of issues over the years. Legislators usually come into the hearing already set in their decisions. That’s just the way it works. Testifying before committees about school choice in particular has given me the opportunity to point to the facts and the data and the track record, which have only grown over time, and allowed me to say, “This is no longer an unknown experience. It works for many, many students and families.”

We have more and more data that show education choice programs work. These programs satisfy parents, they provide positive academic outcomes, and the financial ramifications are negligible or even beneficial. Whenever I’ve had the opportunity to testify, even if the particular legislators in the room were not persuaded, it was an opportunity to get the word out there, to challenge people who are paying attention.

When the spotlight is shining on you at the hearing, you have the opportunity to highlight the growing evidence of success and answer technical questions and deflate some of the myths that are out there. It’s an opportunity to educate a broader audience and to speak on behalf of families who need those options.

reimaginED: You’ve recently started a new chapter in your career as policy director for education choice at ExcelinEd. How did that opportunity come about, and what would you like to accomplish in your new role?

DeGrow: I learned that the Foundation needed to fill a position on its opportunities team. They were looking for someone to provide research and leadership to help advance both public and private school choice options. I was attracted to the opportunity to have an impact in multiple states at a point when many states have recently created or expanded private school choice programs, to help craft effective policies, to make them as effective as possible and to remove as many of the hiccups as possible. That opportunity was very hard to resist.

At the same time, there is the task of implementing these programs, which will be critical. The extent to which I can support those efforts to apply best practices in those states, keeping students at the forefront, will be important. Every time a challenge is successfully met, it’s a feather in the cap for education choice that shows other states that they, too, can help families and do this well. If states are not meeting challenges effectively, it makes it more difficult for other states to implement education choice programs. Having a hand in providing assistance to advance these important policies is an honor, and I’m looking forward to getting to work.

reimaginED: What do you see on the horizon for education choice? How do you see progressive education choice legislation, such as the expansion of education savings accounts, further expanding education choice opportunities for families?

DeGrow: I think we’ve crossed the threshold from just seeing these programs as being beneficial for students with special needs, those who are at risk and those who are from lower-income families, to recognizing that education freedom is an opportunity across the board for all students. I think we’ll see more states follow West Virginia and Arizona and other states that are looking at universal education savings accounts as an opportunity to reach a broader group of students and families who may have been overlooked. So, I think just building the coalition for expanded education choice, universal education savings accounts, and making sure the policies are constructed thoughtfully and implemented effectively will be a big focus of the movement for the next couple of years.

reimaginED: You are the father of three daughters. What kind of educational environment would you like them to inherit?

DeGrow: I started public policy work before my kids were born. When you become a parent, it makes you that much more serious about the work. You understand in a more concrete sense what other parents are going through when their children are in an unsuitable or unhealthy school environment.

Our children have experienced charter schools and homeschooling. We have appreciated the flexibility and opportunity we’ve had to pursue those options. We know some families have that opportunity, but not all do. It gives me even more of a motivation to support things like education savings accounts, hybrid models and microschools that provide more access to families and the sound policies that support them, seeing how this kind of flexibility has helped my kids on their paths.

I hope my daughters will continue to explore their interests and find their place in the world and appreciate all the ways we’ve invested in them, and that wherever they go next, they will benefit from having had education choice.

Editor’s note: Former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush advocates for an “unbundled” education of the future after two years of disrupted schooling in this opinion piece circulated by ExcelinEd, the organization for which he is founder and chairman. The commentary published originally in the Miami Herald.

Editor’s note: Former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush advocates for an “unbundled” education of the future after two years of disrupted schooling in this opinion piece circulated by ExcelinEd, the organization for which he is founder and chairman. The commentary published originally in the Miami Herald.

Last month marked two years since the pandemic swept across the country, causing the largest disruption to our nation’s education system in modern history. But at last, this spring brings an academic revival of sorts.

Schools are remaining open, mask mandates are disappearing and plexiglass dividers between students in their classrooms are coming down. In the rush to return to normal, we owe it to our nation’s children to emerge from this pandemic transformed, not by going backwards, but ready to forge a better future for them with all we’ve learned.

Our starting point is challenging. Prior to the pandemic, America’s public schools were struggling to serve the needs of students, and since the pandemic, a study by McKinsey found students have fallen months behind as a result of school closures and disruptions.

There were severe impacts on student mental health, too. Pew Charitable Trusts found students are reporting significantly increased levels of grief, anxiety and depression. It’s also no surprise that there’s a growing distrust in public education. A survey by Ipsos found trust in teachers declined during the pandemic, and there’s been a subsequent decrease in the number of students enrolling in public school.

Those are serious setbacks, but there are reasons for optimism. The pandemic put a spotlight on a myriad of possibilities for the future of education. Notably, it illustrated a desperate need by families for a broadened ecosystem of options for their children, with funding flexibility to create more equity in choice.

And it elevated the power of parents to blaze new educational pathways for their children. The Associated Press recently reported that homeschooling remains a popular choice for parents, despite schools reopening.

And, private schools and public charter schools have witnessed increased enrollment. But choice, in and of itself, isn’t enough. Policymakers must continue to seek new ways to unbundle education systems, transforming old approaches into new and better learning options.

In Indiana, lawmakers, led by House Speaker Todd Huston, took the first step toward creating the nation’s first “parent-teacher compact” law. This innovative policy would allow parents to directly hire teachers. Educators would continue to be paid by the state and receive their health and retirement benefits, but this policy would enable parents and educators to enter into a peer-to-peer relationship to benefit individual students, without the hurdle of a district middleman.

This individualized approach to education would give educators more freedom, families more flexibility and individual students the personalized experience they may need.

As we unbundle education, we need to reimagine all aspects of how education is delivered to students. One approach is enacting new part-time enrollment policies. Right now, students are defined by the school in which they’re enrolled. Lawmakers can improve the education experience by allowing students to have more flexibility, whereby a student can enroll in their local public school and easily access a portion of their education funding to also enroll part-time in a private school, with an online provider, or engage in another learning experience that benefits the child’s education.

Another approach that complements unbundling is rethinking education transportation options. Last year, Gov. Doug Ducey awarded $18 million in grants to modernize Arizona’s K-12 transportation system, including direct-to-family grants to help close transportation gaps.

In Oklahoma this year, Gov. Kevin Stitt proposed changing Oklahoma’s school transportation funding formula to expand how public school buses can serve students.

And Florida’s Legislature recently passed legislation to create a new $15 million transportation grant program that encourages districts to create innovate approaches to school transportation, including carpooling and ride sharing apps, for both school-of-choice families and traditional school students.

Those are just a few examples, and we must continually look for more ways to unbundle and reimagine education. The pandemic saw an explosion of families, in all communities and from all demographics, embrace micro schools, homeschooling and customized learning pods. Rather than trying to limit these families, we should give them access to direct funds to further personalize and benefit their child’s out-of-school learning experience.

That’s what Gov. Brad Little has championed in Idaho. In response to school closures in 2020, Little used federal emergency COVID relief funds to provide direct grants to families to support students who were no longer learning in school. And this year, Little signed the Empowering Parents Grant Program into law, giving qualifying families up to $3,000 to use for tutoring, educational material, digital devices or internet connectivity.

All of this and more is possible, but it requires policymakers to embrace something many have heard me repeat: Reform is never finished, and success is never final. Transforming our nation’s education system and ensuring students receive the individualized experience to unlock potential and lifelong success require continual forward momentum, especially after two years of disruptions. We have to keep moving, keep reimagining, keep transforming.

This commitment to excellence is a point of pride for Florida. Last year, Florida’s Legislature passed some of the most significant improvements and expansions to the state’s school-choice programs. And this year, lawmakers strengthened the charter school law, expanded the Florida Empowerment scholarship program, created a new financial literacy requirement for high school graduates and ensured parents are better informed of their child’s progress through online diagnostic progress monitoring and end-of-year summative tests.

Settling for familiar, traditional approaches to education shortchanges our children. They deserve more learning options today and skills for a future we’ve yet to imagine. Coming out of this pandemic, lawmakers across the country should embrace every student-centered policy possible and make year-after-year progress in transforming education the guaranteed way to improve their state, serve their constituents and deliver on the promise of a quality education for all their students.

The classic arcade game Punch-Out!! asked players to assume the role of a green-haired boxer named “Little Mac” to box with much larger opponents, like the terrifying Bald Bull. Despite his tiny size, Little Mac could sometimes do things like this to much larger opponents:

The classic arcade game Punch-Out!! asked players to assume the role of a green-haired boxer named “Little Mac” to box with much larger opponents, like the terrifying Bald Bull. Despite his tiny size, Little Mac could sometimes do things like this to much larger opponents:

https://thumbs.gfycat.com/DelightfulNastyAcornbarnacle-small.gif

The story I would like to tell today features my home state of Arizona playing the role of Little Mac in the recent U.S. News & World Report high school rankings to much larger states, including Florida. (Florida, however, has a secret punch in its arsenal – more on that below.)

So: Here is the Little Mac story.

Two Arizona high schools made the top 10 in the recent U.S. News national rankings and 11 made the top 100. While Arizona comprises only 2 percent of the students in the United States, it boasts 11 percent of the top 100 high schools. California, the nation’s most populous state with a public-school system enrolling 6.2 million students (compared to our 1.2 million), tied Arizona with 11 schools in the top 100. Mega-states Texas and New York also landed 11 schools in the top 100 and Florida had 10. No other state scored in the double digits.

“Punching above our weight” would not be an overstatement to describe Arizona’s results in both state and national achievement measures. But … not so fast, my friend!

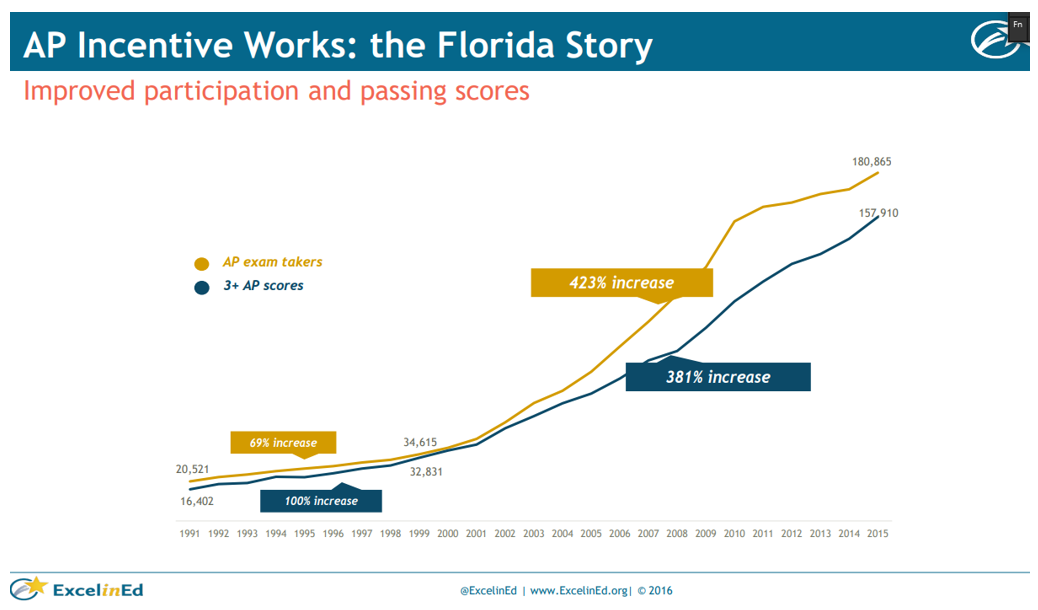

College credit by exam features very prominently in the rankings, which is fine to include, but it’s not a terribly broad measure. The U.S. News & World Report methodology judges individual schools, but the number of schools making a national top 100 list is a very narrow measure. Our friends at ExcelinEd utilize charts like the one below that show broad statewide improvement in students earning credit by exam in Florida:

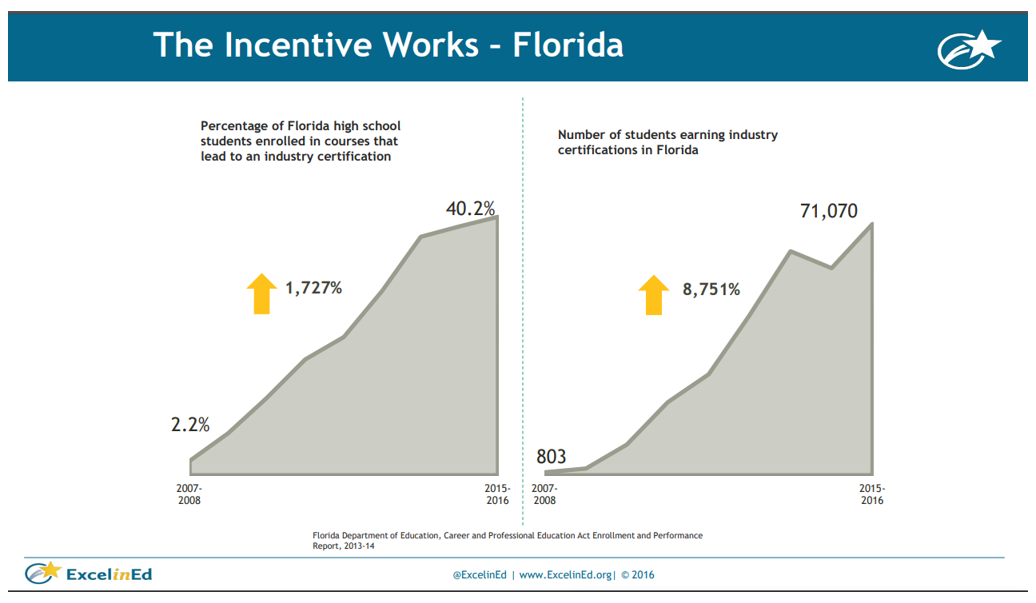

Moreover, there is no reason for high school rankings to credit schools for earning college credit by exam and not for earning high-demand professional certifications. High schools should prepare students for success in college or a career (or both), but how to reach that decision should be made by students and their families. Schools that equip students with high-demand certifications deserve credit as well, in my opinion.

This is not an either-or proposition. Students earning industry certifications often graduate from college. Students earning college credit by exam don’t always finish college and could have benefited from a back-up plan. Ideally, schools would both prepare students to master college-level work and give them the opportunity to earn certifications with value in the labor market.

Florida pioneered a set of policies to encourage schools to earn college credits and later launched a similar effort to encourage high schools to allow students to earn high-demand certifications. If I were ranking high schools, unlike U.S. News & World Report, I’d rank such things equally.

Here is ExcelinEd’s chart showing trends in certifications among Florida high school students.

It appears that in addition to 158,000 passing scores on college credit exams in 2015, Florida high school students earned more than 71,000 certifications. By the way, 166,540 students graduated from Florida public schools at the conclusion of the 2015-16 academic year. We can therefore safely assume that a majority of Florida students either earned college credit by exam or earned a certification in a high demand field – or accomplished both.

So, how would U.S. News and World Report rankings for other states look if certifications were included in the rankings? We can’t be sure, but here’s a guess.

https://gfycat.com/ornerypowerlessazurewingedmagpie

You, dear reader, look as though you could use some distraction from the viral apocalypse. Like many good stories, this one flashes back to the past to inform the present.

You, dear reader, look as though you could use some distraction from the viral apocalypse. Like many good stories, this one flashes back to the past to inform the present.

A decade ago, while an analyst at the Goldwater Institute, I participated in a debate concerning choice versus curriculum reform. Yes, people were confused about whether those things were mutually exclusive a decade ago, as they are today. (Spoiler alert: choice helps curriculum reform).

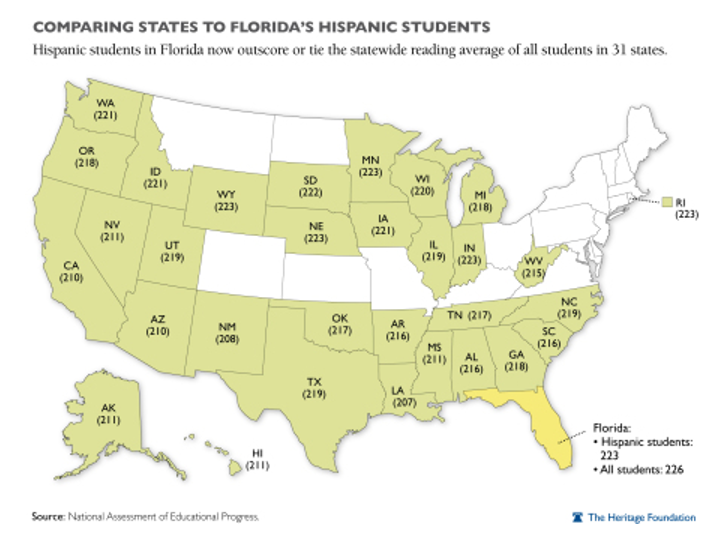

In any case, the debate prompted me to ask myself which states had done a lot of both choice and testing accountability. This in turn led me to look closely at the NAEP scores of Florida and to consider that former Gov. Jeb Bush had aggressively sought to improve literacy instruction by creating a variety of public and private choice mechanisms.

Staring at fourth-grade NAEP scores by race/ethnicity on my computer screen, here is what I discovered.

The conversation around K-12 in Arizona at the time frequently involved an “if you control for student demographics, we are kind of average” story. This was part of a fable with a thousand faces; you will hear different versions of it in different states. In Arizona, the story involved kids immigrating from Mexico who were unable to read Spanish. In Minnesota, I’ve heard tales told in hushed voices about Hmong kids. In more than one southern state, I’ve heard allusions to scores of white kids scoring quite high when they weren’t anything of the sort. The details vary, but the moral is always the same: “We here in state X, we’ve got the really hard-to-educate kids.”

The fact that Florida’s Hispanic students were reading approximately a grade level higher than the average for all students in Arizona required the development of a new rationale. That new rationale was the magic Cuban theory. Florida’s Hispanics are Cubans, the story went, and they are wealthy. “Obviously we can’t expect to do that with our Hispanic students,” the theory concluded.

I related the magic Cuban theory to an audience at the first ExcelinEd conference held in Orlando. Given the advantage of local knowledge held by many audience members, the crowd laughed out loud at the absurdity of the stereotype. Despite living in a distant patch of cactus, I had spent enough time in the Florida Keys with my grandfather to develop a lifelong taste for ropas viejas and to know better.

The magic Cuban theory could never survive scrutiny. First off, Florida’s Hispanic community is vastly more diverse than appreciated by distant stereotypes, with Cubans constituting a minority among Hispanics. Second, Florida saw large increases in literacy among multiple ethnic groups. Magic Haitian theory anyone?

Finally, buried deep in the data explorer, NAEP has a variable that allows you to break down Hispanics by subgroup. NAEP, alas, discontinued this variable, but we do have it for both 1998 (the year before Jeb Bush took office) and 2002. It would have been great to have data from additional years, but note that the 2002 NAEP came before the adoption of the third-grade retention policy. Between 1998 and 2002, Florida policymakers had adopted major education reforms, but not all the reforms.

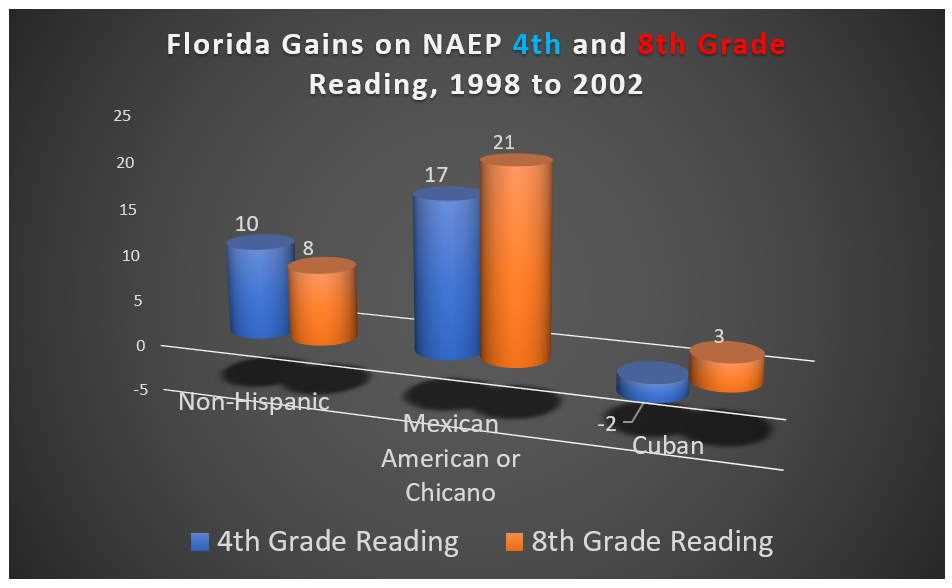

Here is what the gains looked like during the 1998 to 2002 period.

Florida’s Cuban-Americans scored well, but they were not driving gains. As a rough rule of thumb, 10 points on NAEP exams approximately equals an average grade level’s worth of progress. In other words, we would expect a group of fifth-graders given the fourth-grade test to do about 10 points better. The Mexican-American gains were very large, very meaningful and very statistically significant.

By the way, those eighth-graders from 2002 are approaching their mid-30s now. With all of today’s troubles, and considering those around the bend, Florida chose wisely in not succumbing to the soft bigotry of low expectations, instead making an all-out effort to teach literacy. Life is hard, but life is really hard if you can’t read.