MIRAMAR, Fla. – Florida’s explosion in à la carte learning has created space for all kinds of new, state-supported educational experiences, including, improbably, a class in building with power tools that’s tucked inside an ashram, a kind of spiritual retreat, with a grove of mango trees and a colony of especially plump iguanas.

The class is run by Builder’s Workshop, an à la carte provider founded by Marvin and Christine Hernandez. The couple retrofitted an old horse stable on the property into a student workshop, humming with saws, drills, and sanders.

Now, just a few months in, they’re already serving 30 students a week, all in middle and high school. Nearly all of them use education savings accounts (ESAs), the flexible state scholarships that are fueling Florida’s fast-growing universe of à la carte learning.

“They say build it and they will come, and people are coming,” Christine said. “Families are hungry for it.”

The same could be said for à la carte learning in Florida.

Enabled by ESAs, à la carte learning is when families use state support to customize their child’s education completely outside of full-time schools, by picking and choosing from multiple providers. This school year, 140,000 students will do à la carte learning in Florida, up from about 8,000 five years ago, and their families will spend more than $1 billion in ESA funds. As we detail in a new data brief, nothing on this scale is happening anywhere else in America.

As the number of à la carte learners expands, so does the supply of places they can go.

Last year, 4,318 providers received ESA funding in Florida, more than double the year prior. Many of them are tutors and therapists. But a growing number are like Builder’s Workshop, specialized, micro-programs that would have been inconceivable as public education just a few years ago.

Inside Builder’s Workshop, students learn how to operate tools safely and confidently. They build birdhouses, step stools, shoe racks, and in one class I visited, “shields of faith.” Along the way, they pick up habits that rarely come from screens.

“Teaching kids to use tools and build things … builds confidence, responsibility, and real-world skills,” Marvin said. “It teaches them problem-solving, patience, and how to work safely. It also strengthens their math and creativity, gets them off screens, and helps them feel capable of making and fixing things.”

“Plus, from a Christian view,” Marvin continued, “it reflects God’s design for us to create and steward the world around us.”

(Builder’s Workshops offers both secular and Christian classes.)

Some Builder’s Workshop students are members of a Montessori co-op that also uses the property. Some are not. In the rapidly evolving world of à la carte learning, lines blur, and kids, families, and educators cross them freely.

“I just love building stuff,” said student Jasmin Hernandez (no relation to Marvin and Christine), a 16-year-old who wants to be a carpenter. Jasmin spoke briefly between noisy cuts with a band saw.

That DIY attitude is what Builders Workshop wants to cultivate.

“We want them to know they can fix a table if they need to fix a table,” Christine said. But “we also want them to know they can create their own products if they want to.”

Marvin and Christine are fixtures in South Florida’s fine arts scene. Marvin is a longtime artist; Christine has a background in project management. Among other services, their company designs and builds custom display cases, pedestals, and other structures for museums, galleries, and private homes.

So, they know their power tools. They also understand the broader potential.

To date, the expansion of ESAs hasn’t done much to enhance career and technical education. But student interest is growing for those skills and jobs, even as some quarters worry about a lack of qualified teachers. Florida, though, is full of highly trained professionals — builders, craftspeople, men and women skilled in the trades — who could be part of the solution.

Maybe ESAs are the bridge that connects them.

Maybe Builder’s Workshop is a glimpse of what that could look like.

Jasmin’s mom, Michelle Hernandez, said her daughter is already close to graduating because she took so many dual enrollment classes through her prior school. So, Michelle decided to homeschool Jasmin and let her explore more nontraditional classes.

Builder’s Workshop, she said, is “an outlet to be creative but with items that have a purpose. Building things also means not having to wait for others to do it, and she can see her own ideas come to life.”

Jasmin’s 13-year-old brother, Cristian, is also enrolled. Michelle said he looks forward to it because hands-on learning registers more deeply with him. Plus, she said, “He’s a boy. He needs to move.”

Kelly Jacobo said likewise about her son, Malakai, who’s also 13 and taking the class.

Jacobo said her grandfather and great-grandfather were accomplished carpenters, so Builder’s Workshop was perfect. “It kind of runs in the family,” she said. “I’ve been praying for forever that there’d be a woodworking class for kids.”

The backdrop for Builder’s Workshop couldn’t be more colorful. Even though it’s in super urbanized South Florida, it’s hidden down a graded road lined with banana trees. Around the corner is the mango grove, where the iguanas, clearly living their best lives, feast when the fruit is in season.

Alas, this setting is going to fade from the story. The owner recently sold the land, so Marvin and Christine will be looking for new digs soon. They don’t anticipate a problem with demand, however, and the families they serve are devoted.

“We don’t know where or when it will happen,” she said of finding a new place, but “we have an immense amount of faith that more families will join once we open our doors.”

By David Heroux and Ron Matus

In the blink of an eye, à la carte learning in Florida has become one of the fastest-growing education choice options in America.

This school year, 140,000 Florida students will participate in à la carte learning via state-supported education savings accounts, up from 8,465 five years ago. Their parents will spend more than $1 billion in ESA funds.

These families are at the forefront of epic change in public education. Completely outside of full-time schools, they’re assembling their own educational programming, mixing and matching from an ever-expanding menu of providers.

Nothing on this scale is happening anywhere else in America.

To give policymakers, philanthropists, and choice advocates a snapshot, we produced this new data brief. In broad strokes, it shows a more diverse and dynamic system where true customization is within reach for any family who wants it.

ESAs shift what’s possible from school choice to education choice. They give more families access not only to private schools, but tutors, therapists, curriculum, and other goods and services.

Adoption of these more flexible choice scholarships has been booming nationwide; 18 states now have them. But nowhere is their full potential more fully on display than in Florida.

Last year, 4,318 à la carte providers in Florida received ESA funding, more than double the year prior. Many of them are tutors and therapists, but a growing number offer more specialized and innovative services, as we highlighted in our first report on à la carte learning. Former public school teachers are also a driving force in creating them, just as they’ve been with microschools.

How far and fast à la carte learning will grow remains to be seen. For now, check out our brief to get a glimpse of what’s ahead.

MIRAMAR, Fla. — William Ivins moved his family to South Florida ahead of his retirement from the United States Marine Corps and enrolled his children at Mother of Our Redeemer Catholic School, hoping they would reap the same rewards as he did from a faith-based education.

But, as William and his wife, Claudia, would soon learn, that was easier said than done.

A lawyer for much of his 20-year career in the Marines, William needed to pass the Florida Bar Exam before he could enter the private sector. It was a long process that left him unemployed for 19 months.

“It was a struggle,” he said. “My retirement income was not enough to pay for the cost of living and tuition for my children.”

The Ivins' faced a few choices: continue with the financial struggle, homeschool their children, send them to their district school, or move out of state. None were appealing to the Ivins, and fortunately, they didn’t have to act on any.

Florida's education choice scholarships managed by Step Up For Students allow his four children to attend Mother of Our Redeemer, a private K-8 Catholic school near the family’s Miramar home.

“It was a perfect storm of having to retire from the Marines and not really having a job lined up,” William said. “The transition was more difficult than I thought it would be. The income just was not available for us to continue our kids’ education in the way we wanted. Had the scholarship not been there, we would have been forced to move out of state or homeschool them or move them to (their district) school.”

In July 2020, the Ivins moved to South Florida from Jacksonville, N.C., where William had been stationed at Camp Lejeune. William contacted Denise Torres, the registrar and ESE coordinator at Mother of Redeemer, before making the move. She told William the school would hold spaces for his children. She later told him about the education choice scholarships managed by Step Up For Students.

“That was a big relief for him,” Torres said.

At his mother’s urging, William began attending Catholic school in high school.

“That was a life-changer for me,” he said.

He converted to Catholicism and vowed if he ever had children, he would send them to Catholic school for the religious and academic benefits.

Rebekah graduated in May from Mother of Our Redeemer. She had been an honor roll student since she stepped on campus three years ago.

“Rebekah likes to be challenged in school, and she was challenged here,” Claudia said.

Rebekah, who received the High Achieving Student Award in April 2022 at Step Up’s annual Rising Stars Awards event, is in the excelsior honors program as a sophomore at Archbishop McCarthy High School.

“She's an amazing, amazing student,” Torres said. “It’s incredible the way she takes care of her brothers. She's very nurturing. Every single teacher has something positive to say about her.”

Rebekah’s brothers, Joseph (seventh grade) and Lucas (fourth grade), do well academically and are active in Mother of Redeemer’s sports scene, running cross-country and track. Nicholas, the youngest of the Ivins children, is in second grade. He was allowed to run with the cross-country team while in kindergarten, which helped build his confidence.

William had been in the Marines for 20 years, eight months. He served as a Judge Advocate and was deployed to Kuwait in 2003 for Operation Iraqi Freedom, to Japan in 2004, and then to Afghanistan in 2012 for Operation Enduring Freedom.

He retired in May 2021 but didn’t find employment until December 2022. The Florida Bar Exam is considered one of the more challenging bar exams in the United States. He took the exam in July 2021 and didn’t learn he passed until September. It took William more than a year before he landed a position with a small law firm in Pembrook Pines.

Claudia, who has a background in finance, works in that department at Mother of Our Redeemer Catholic Church, located next to the school.

“They have really become part of our community,” Principal Ana Casariego said. “The parents are very involved and are big supporters of our school and church.”

In Mother of Our Redeemer Catholic School and Church, Willian and Claudia found the educational and faith setting they wanted for their children.

“It is a small community environment where you know all the teachers and staff by first name,” William said. “My kids have received a wonderful education in an environment where they don’t have to worry about bullying, and they can really strive to grow and do their best academically.

“The scholarship kept us in the state and kept our kids in the school system that we wanted them to be in. It’s been a great blessing to us.”

JACKSONVILLE, Fla. – Four years ago, Phil and Cathy Watson were distressed and desperate. Their daughter Mikayla, then 12, was born with a rare genetic condition that led to physical and cognitive delays. With her school situation getting worse by the day, they needed options, now.

The Watsons were open to private schools. But they couldn’t find a single one near their home in metro D.C. that met Mikayla’s needs. They even looked in neighboring states. Nothing.

One day, though, Phil varied his keyword search slightly, and something new popped up:

A school for students with special needs that had low student-to-staff ratios, transition programs to help students live independently, even an equine therapy program.

The Watsons feared it was too good to be true. Even if it wasn’t, it was 700 miles away.

A destination for education

Florida has always been a magnet for transplants. It’s tough to beat sunshine, low taxes, and hundreds of miles of beach. But as Florida has cemented its reputation as the national leader in school choice, the ability to have exactly the school you want for your kids is making Florida a destination, too.

In South Florida, Jewish families are flocking from states like New York to a Jewish schools sector that has nearly doubled in 15 years. But they’re not alone. Families of students with special needs are making a beeline for specialized schools, too. The one the Watsons stumbled on has 24 students whose families moved from other states – about 10% of total enrollment.

The common denominator is the most diverse and dynamic private school sector in America, energized by 500,000 students using education choice scholarships.

According to the most recent federal data, the number of private schools in Maryland shrank by 7% between 2011-12 and 2021-22. In Florida, it grew by 40%.

“What Florida is offering is just mind blowing compared to Maryland,” Phil said. “If a story like this ran on the national news, people would be beating the door down.”

‘The kid who never spoke’

Phil and Cathy Watson have six children, all adopted. They range in age from 1 to 39. All have special challenges.

“God picked out the six kids we have,” said Cathy, who, like Phil, is the child of a pastor. “We feel very strongly that we were called to do what we do. Our heart says we have love to give and knowledge to share. These kids need that, so it’s a match.”

Mikayla is their fourth child. She was born with hereditary spastic paraplegia, a condition that causes progressive damage to the nervous system.

She didn’t begin walking until she was 18 months old. Even then, her gait continued to be heavy-footed, and she was prone to falling. Her speech was also, in Phil’s description, “mushy,” and until she was 12, she didn’t talk much.

In many ways, Mikayla is a typical teen. She loves steak and sushi and Fuego Takis. Her favorite books are “The Baby-Sitters Club” series, and her favorite movies include “Beauty and the Beast” and “Beverly Hills Chihuahua.” Many of her former classmates, though, probably had no idea.

In school, Mikayla was “the kid who never spoke.”

Checking a box

As Mikayla got older, she and her parents grew increasingly frustrated with what was happening in the classroom. “She was being pushed aside,” Phil said.

Teachers would tell her to read in a corner. Between the physical pain from her condition and the emotional turmoil of being isolated, she was crushed. Sometimes, Phil said, she’d come home and “unleash this fury on my wife and I.”

The pandemic made things worse. In sixth grade, Mikayla was online with 65 other students. Then, three days before the start of seventh grade, the district said it no longer had the resources to support her with extra staff. Instead, she could be mainstreamed without the supports; enroll in a private school; or do a “hospital homebound” program.

The Watsons chose the latter. Three days a week, a district employee sat with Mikayla, going over worksheets that Phil said were “way over her head.”

“All it was,” he said, “was checking a box.”

Just in the nick of time, the school search turned up a hit.

Florida, the land of sunshine and learning options

What surfaced was the North Florida School of Special Education.

“From just the pictures, I’m thinking, ‘This looks legit,’ “ Phil said. “Both of us are like, ‘Wow.’ “

When the Watsons called NFSSE, as it’s called for short, an administrator answered every question in detail. This was not the experience they had with some of the other private schools they called.

At the time, Phil owned a home building company, and Cathy worked for a counseling ministry. They lived comfortably. But they were also paying tuition for another daughter in college.

Thankfully, the administrator told them Florida had school choice scholarships. For students with special needs, they provided $10,000 or more a year.

The Watsons couldn’t believe it. They were familiar with the concept of school choice but didn’t know the details. Maryland does not have a comparable program.

The administrator also told them NFSSE had a wait list. But the Watsons had heard enough.

A fortuitous phone call

A few weeks later, they were touring the school.

The facilities were stellar. Even better, the administrator leading their tour knew the name of every student they passed in the hallways. “We were blown away,” Phil said. “They truly care. “

At some point, the staff ushered Mikayla into a classroom. As her parents watched from behind one-way glass, another student greeted Mikayla with a flower made of LEGO bricks.

For years, Mikayla had been withdrawn around other students. Not here. The shift was immediate. She and the other students were using tablets to play an interactive academic game, and “you could see her turn and laugh with the kids next to her,” Phil said.

Minutes later, he and Cathy were in the administrator’s office, “bawling our eyes out.”

“We said, ‘We’re all in. We have to be here. We’ll be here next week if that’s what we have to do.’”

Days later, the Watsons were at Disney World when NFSSE called. Unexpectedly, the family of a longtime student was moving. The school had an opening.

New friends, improved skills and boosted confidence

Even without the choice scholarship, the Watsons would have moved. At the same time, the scholarship was invaluable. The cost was not sustainable in the long run, Phil said, especially because he had to re-start his business.

The Watsons rented a long-term Airbnb and then an apartment before buying a house in Jacksonville. They uprooted themselves completely from Maryland, including selling their dream home.

“That was hard,” Cathy said. “You’re leaving everything you love.”

Mikayla’s turnaround, though, has made it all worthwhile.

Mikayla was reading at a first-grade level when she arrived at NFSSE; now she’s at a seventh-grade level. She loves the new graphic design class. She won an award for completing 1,000 math problems. “When she got here, she couldn’t add two plus two,” Phil said.

Her verbal skills have blossomed. She eventually told her parents something she didn’t have the ability to tell them before: In her prior school, she didn’t talk because other students laughed at her.

At NFSSE, the “kid who never spoke” speaks quite a bit.

One day, she served as “teacher for the day” in her personal economics class, delivering a lesson on how to make change.

Mikayla is kind and quick to smile. She is surrounded by friends and admirers. “Mikayla is my best friend,” said a chatty girl with pigtails who waited by her side in the hallway.

One boy held the door for Mikayla as she headed to her next class. A second hung her backpack on the back of her wheelchair. A third walked her to P.E.

Mikayla’s confidence is growing outside of school, too.

In the past, she wouldn’t say hi or order in a restaurant. But at Walmart the other day, Phil needed a card for a friend’s retirement, so Mikayla went to find a clerk. She came back and told him, “Aisle 9.”

Mikayla has a bank account and a debit card. She tracks the money she earns from chores. She routinely uses the notes app on her phone to mitigate challenges with short-term memory.

NFSSE, Cathy said, is constantly reinforcing skills and strategies to foster independence. It “pushes for potential,” just like the families do.

Mikayla “sees that potential now; she’s excited now,” she said.

Before NFSSE, the Watsons didn’t think Mikayla could live independently. Now they do.

The school and the scholarship, Phil said, have “given Mikayla an opportunity for her life that we didn’t know existed.”

He credited the state of Florida, too, for creating an education system where more schools like NFSSE can thrive.

If only every state did that.

TAVERNIER, Fla. – Every year, millions of students across America learn the foundational concept of place value in math. But it’s a safe bet few of them learn it at the beach.

At the first microschool in the Florida Keys, that’s exactly what a handful of kindergartners and first graders were doing with their teacher last week. Standing in the shade of buttonwoods on the edge of the Atlantic, they used mahogany seed pods, mangrove propagules, and sea grape leaves to help their brains grasp the idea.

In Florida, this is public education.

The students all use state-supported school choice scholarships to attend Coastal Glades Microschool, a new elementary school founded by former public school teachers Samantha Simpson and Jennifer Lavoie. Both 13-year educators, Simpson and Lavoie wanted a school that reflected their preferred approach to teaching and learning, as well as the goals and values of the families they sought to serve.

The result: Coastal Glades is Montessori-based, immersed in the outdoors, and deeply tied to the local community.

It’s also totally theirs to run as they see fit.

“We’re free. We own it. We don’t have anyone telling us what to do,” Lavoie said. “That’s priceless.”

Florida is leading the country in education freedom, with more than 500,000 students now using choice scholarships. Coastal Glades is another distinctive example of what that freedom looks like.

Microschools are popping up by the hundreds. Former public school teachers are the vanguard in creating them. All the new learning options are stunning, not just in volume but in diversity. In Florida, at least 150 Montessori schools participate in the choice scholarship programs, and at last count, at least 40 “nature schools” serve Florida families, too.

This movement is self-propelled. It’s driven by parents, teachers, and communities who are realizing more every day that public education is in the middle of a sea change. Now, they get to decide what “a good education” looks like.

For the past six years, Simpson and Lavoie worked together at the same school. As choice options exploded around them, freedom kept tapping them on the shoulder.

“We said, ‘Wouldn’t it be nice if we could just pick up these four walls and move? And it just be us?’” Lavoie said.

To get their bearings, Simpson called a friend, another former public school teacher who founded a microschool. This one happened to be 90 miles north in Broward County, the unofficial microschool capital of America. The friend gave her good advice. She also said starting her own school was “the best thing I’ve ever done.”

Learning at Coastal Glades is proudly “place based.” The colorful communities that populate the islands between the Everglades and the sea are an endless source of exploration and inspiration. Simpson and Lavoie want their students to know and love where they live, so they can grow up to be good citizens and thoughtful stewards.

“Being in the community, being in nature, that’s where you’re going to learn,” Simpson said.

The students learned about bees from a local guy who harvests mangrove honey. They visited a berry farm on the mainland. Even more exotic trips are on tap: To Everglades National Park. To the Keys’ sea turtle hospital. Even to a reef where the students will be able to snorkel near nurse sharks. “We want them to learn that some scary things are not really scary,” Simpson said.

Nearly every day, the students visit natural areas for play-based learning. After the math lesson beneath the buttonwoods, for example, they went hunting for hermit crabs and jellyfish.

“This is just as important as testing, as reading, as anything,” Simpson said. “We want to bring back childhood and the love of learning.”

That’s exactly why Alejandra Reyes enrolled her 5-year-old daughter, Daniella. Daniella’s curiosity is blossoming, Reyes said, because she’s in a small school with more individualized attention and more hands-on learning.

“I didn’t want her to be in class sitting down all day. She’s such a free-spirited little girl,” said Reyes, a stay-at-home mom whose husband is a marine mechanic. “She’s learning so much on her little adventures. It’s, ‘What’s this? What’s that? Let’s look it up.’ “

“We got so lucky that my daughter’s first experience with school is this microschool.”

Simpson and Lavoie like the state of Florida’s academic standards. They use them to guide instruction. But they’re not tethered to pacing guides, and they can switch gears or directions whenever it makes sense. They do that often with their one older student, a fifth grader who was bored in his prior school because he wasn’t being challenged.

At the beach the other day, the older student got to learn about mass, volume, density, and buoyancy while his younger classmates were doing the lesson on place value.

Simpson set out two buckets, one filled with freshwater, one filled with saltwater. The student built a mini boat out of aluminum foil to float on the surface of each, then carefully piled pennies into it to see which boat in which bucket could sustain the most weight. (The one in saltwater won.)

“He loves engineering and problem solving,” Simpson said. And the school has the flexibility to accommodate him with more advanced lessons.

As it becomes even more mainstream, school choice in Florida is experiencing some growing pains. Coastal Glades represents some of those challenges, too.

For classroom space, the school rents a 250-square-foot room in a church. The church meets fire codes for dozens of parishioners, but not for a handful of students. Coastal Glades isn’t the only unconventional learning option to learn about fire codes the hard way – see here, here, and here – but its predicament takes the cake.

In lieu of installing an expensive sprinkler system, which Simpson and Lavoie could not afford, the pair hired a local firefighter, at $37 an hour, to hang out while students were in the building. Since the additional requirements only kick in when there are more than five students, Coastal Glades was able to drop the firefighter as long as it capped enrollment.

Next year, the school will be in another building that shouldn’t have those issues, which means it will be able to serve more families.

Word’s already out on the “coconut telegraph” – that’s Keys-speak for grapevine – that the new school will be growing.

Reyes has no doubt that other parents will respond the same way she did.

“Times have changed. Schools are different,” she said. “What kid doesn’t want to be learning outdoors?”

So last week I related the incredibly weak evidence for the “death” of district schooling in Arizona. That evidence shows flat to gently sloping enrollment district enrollment, all-time highs for spending and remarkable academic improvement. Given that Arizona districts look more like an Olympic gold medalist than a corpse, I decided to check Florida for signs of mortality.

Behold: the “death” of Florida district education:

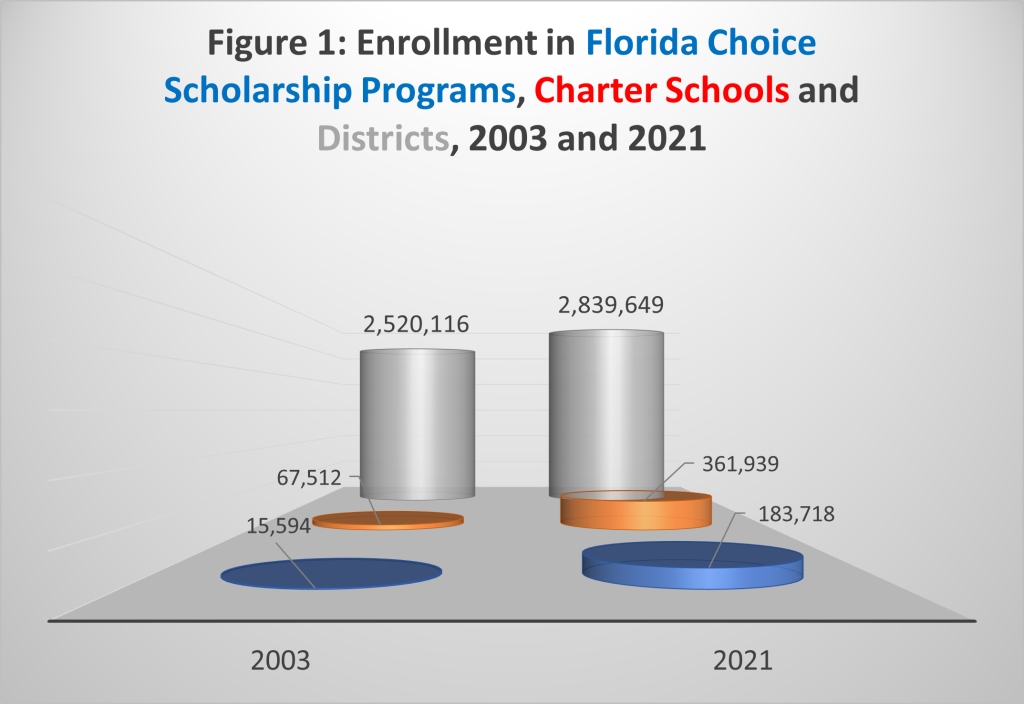

Rather than “dying” Florida school districts have added a number of students more than three times the size of the K-12 enrollment of Wyoming between 2003 and 2021 despite the growth of choice options. Moreover, Florida’s spending per pupil increased faster than inflation during this period, so more students and a higher real spending per pupil is a very odd way to “destroy” school districts.

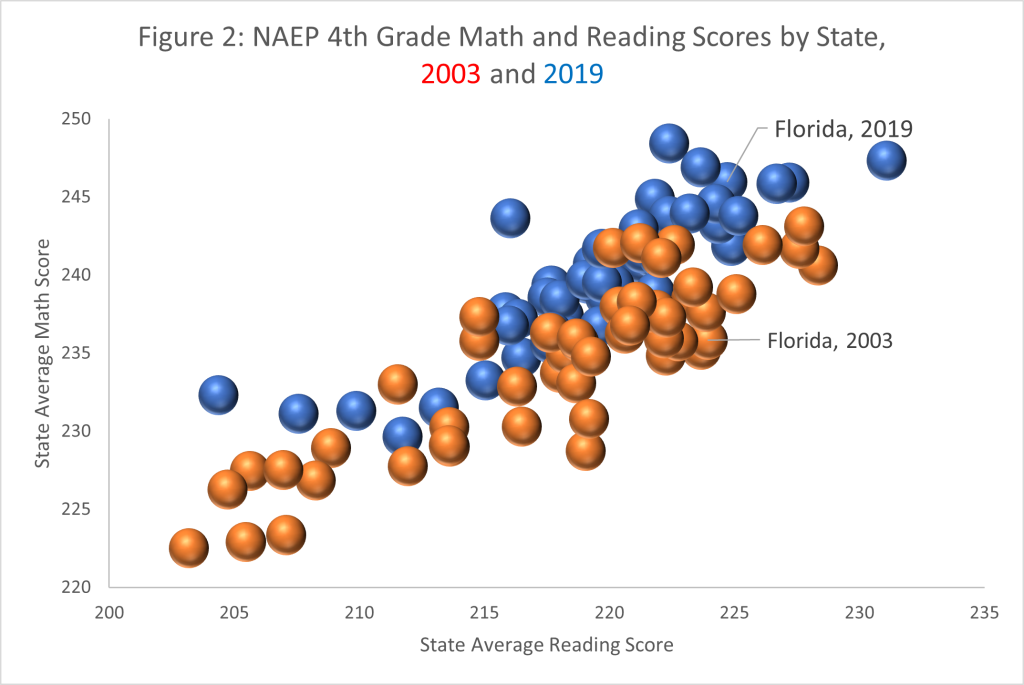

Private choice enrollment has grown since 2021 (the latest data available across sectors) and now is likely slightly above Florida charter school enrollment. That would be because Florida’s lawmakers have (wisely) adopted policies to create a demand-driven K-12 system. Let’s check the NAEP to see how that went pre-pandemic:

Not bad, especially considering that Florida made huge NAEP progress before 2003 (before all states began participating in NAEP). As you can see from Figure 1, a large majority of Florida students still attend district schools, so we can safely infer that those district schools perform far better than they did before the advent of choice in the 1990s.

Fourth graders make volcanoes in science lab at the Children's Reading Center Charter School in Palatka, Florida

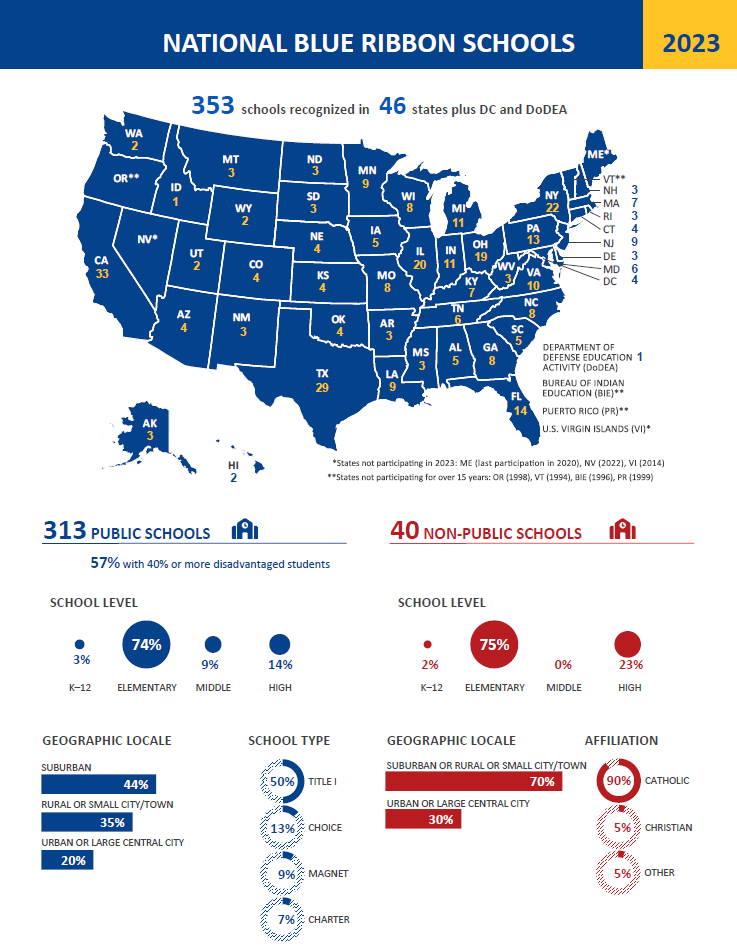

Across Florida, 14 schools received National Blue Ribbon honors this year from the U.S. Department of Education.

Those recognized for exemplary performance include a Catholic school, five magnet or choice schools and five charter schools.

Among the winners is a charter school based in rural Putnam County that focuses on the needs of economically disadvantaged students. The Children’s Reading Center of Palatka uses a self-paced model that rejects traditional textbooks. Instead, teachers design their own lessons based on students’ needs.

“We focus on a standard for as long as needed until children are comfortable moving forward. There are no boxed curriculums at our school!” the school says on its Blue Ribbon profile page. The Title I school serves 257 students in kindergarten through sixth grade.

MAST@FIU was among the Sunshine State’s magnet winners. Situated on Florida International University’s Biscayne Bay campus, it represents a collaboration between the university and the Miami-Dade School District. It offers a blend of face-to-face instruction and community-based projects with a focus on marine and environmental science.

Queen of Peace Catholic Academy of Gainesville, which serves 470 students in kindergarten through sixth grade, was a repeat winner, having made the national list in 2011. It was the only private school on the list this year.

The U.S. Department of Education has given the awards annually for 40 years to more than 9,000 schools across the nation.

All schools are recognized based on test scores for all students, test scores among subgroups and graduation rates for either high performance or closing achievement gaps. The list of gap-closing schools is shorter and includes no Florida schools this year.

Students at St. Lawrence Catholic School in Tampa brought their bright smiles and are ready to start the school year.

School is back in session for Catholic schools across all seven dioceses in Florida.

This year, each of them is seeing another enrollment increase.

This broad, widespread enrollment growth is part of a longer-term trend that makes Florida stand out on the national landscape.

In a recent report published by Step Up For Students, only 10 states showed growth in Catholic school enrollment over the past decade. Of those 10, Florida is the only state with a significant number of students enrolled in Catholic schools.

These numbers may continue to change as some schools are still enrolling new students, but here is a preliminary look at year-over-year enrollment growth by diocese.

Diocese of Venice – 8%

Diocese of Palm Beach – 6%

Diocese of St. Augustine – 5%

Archdiocese of Miami – 3.5%

Diocese of St. Petersburg – 3.5%

Diocese of Orlando – 3%

Diocese of Pensacola/Tallahassee – 2%

Katie Kervi, Assistant Superintendent for the Diocese of Palm Beach, said that over the last three years enrollment in the diocese’s schools has grown by at least 6%.

“We are excited to see our schools flourishing and look forward to welcoming new students and families into our community,” she said. “Our Catholic schools provide a faith-based education paired with high academic standards. I believe the consistent increases in enrollment can be attributed to these strong foundations and because all families now have the opportunity to choose the educational environment that is best for their children.”

Legislation that went into effect on July 1 made the state’s Family Empowerment Scholarships available to all students who are eligible for K-12 public education.

Alina Mychka’s daughter was awarded a scholarship for the 2023-24 school year by Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog.

Her child started the year at Holy Family Catholic School in Jacksonville, and she says she is thankful she can send her child to a safe environment with a rigorous curriculum that reinforces her values.

Mychka immigrated to America from Ukraine eight years ago. She sends any extra dollars her family can spare back to her relatives in their war-ravaged home country.

Without the scholarship, she says, Catholic school would likely not be an option for her family.

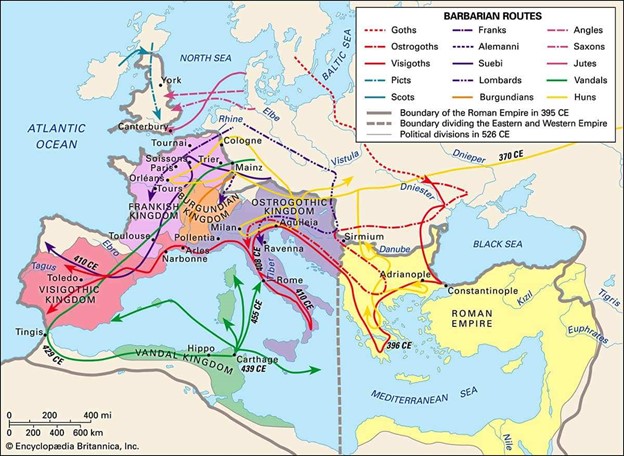

In 410, after years of enough backstabbing, civil wars and barbarian invasions to make a Games of Thrones scriptwriter blush, the Saxons invaded the Roman province of Britannia. The Roman Britons called upon the emperor for aid, which resulted in what is known as the Rescript of Honorius. In this rescript (a formal reply) Emperor Honorius, distracted by internal rebellion and Visigoth invasion, related “Britannia must look to her own defense.” It was not apparent then, but centuries of Roman rule over Britain ended.

Florida families suffered an Honorius-style rescript of their own in 2020 with the closure of schools. One can only describe the damage suffered by students as horrifying, and it could have been worse. The Florida Education Association, for example, pursued litigation all the way to the Florida Supreme Court in the hope of keeping schools closed. The case went against the FEA, but the message was clear: you are on your own.

Florida families evidently have not forgotten, as Step Up for Students has awarded 410,365 full-time scholarships under Florida’s expanded choice policies. Florida families are filing approximately 1,400 new applications daily. Being less dependent on a group of people eager to throw your children overboard when times get tough apparently appeals to many.

That constitutes a promising start, but it understates the significance of Florida’s new universal eligibility: Every Florida student now has an exit option. The ability to leave and take your money with you isn’t just a form of accountability; it’s the ultimate form of accountability. All Florida students will benefit from the universal expansion of choice regardless of whether they use the program.

American families must look to the defense of their children, and states like Florida have empowered them to do just that. Not coincidentally Americans have been moving to Florida in astounding numbers. Dominoes will accordingly continue to fall.

In 2019, just months away from what became the COVID-19 schooling debacle, this blog included a discussion of Robert Pondiscio’s concept of the “Tiffany Test.” Pondiscio defined students as a “Tiffany” if they had bought into the promise of education but had been let down by the system. The post included the following prediction:

"Maybe it’s a little early, maybe the time is not quite yet, but the day is coming when our K-12 policies will fully and appropriately respect the dignity of families to exercise autonomy in schooling. When that day comes, the unfulfilled, the disappointed, the mistreated, the misfit, and the dreamer will seek better situations for themselves.

They won’t ask for permission but rather will be exercising their rights as free people. Pleading with adults to do what is right won’t be the first or only option. When that day comes, “Tiffany” can speak softly, but her voice will be imperial; the system will center around her at last."

There was no shortage of Tiffany students in 2019 but a great many more beginning in 2020. In Florida and many other states, they’ll be in charge of their own education.

When Florida lawmakers debated HB 1 earlier this year, the discussion largely focused on how the legislation would dramatically expand education choice through universal eligibility and flexible spending options for families.

Another part of the bill inspired far less discussion but got the attention of school district leaders across the state: a review of public school regulations.

By Nov. 1, the state Board of Education must develop and recommend “potential repeals and revisions” to the state’s education code “to reduce regulation of public schools.”

“This is a great step towards keeping our public schools competitive” in an era of expanded options, said Bill Montford, a former Democratic state Senator from North Florida who heads the Florida Association of District School Superintendents.

“Traditional, neighborhood public schools have been, and will continue to be, the backbone of our K12 education system,” he

Bill Montford

said. “We want our schools to be the first choice for parents, not the default choice, and to do that we need to reduce some of the outdated, unnecessary, and quite frankly, burdensome regulations that public schools have to abide by,”

Before they propose any changes, state board members must consider feedback from a diverse group that includes teachers, superintendents, administrators, school boards, public and private post-secondary institutions and home educators.

To fulfill that requirement, board members set up a survey link that will accept suggestions through today. A group of superintendents submitted a recommendation list that covers topics that include construction costs, budgets, enrollment, school choice, instructional delivery and accountability. Their pitches included proposals to:

"We’d like for them to recognize all parental choice equally and give school districts the same flexibility and opportunity to innovate provided to other publicly funded options,” said Brian Moore, general counsel for the superintendents association that Montford leads. He added that the superintendents would like to see more cooperation between school districts and the Department of Education.

This effort isn’t the first the state has made to provide school districts with relief from what they see as burdensome regulations. But to some leaders the process seems more like a game of Whac-A-Mole, with new regulations soon replacing the ones that get repealed.

Ten years ago, Gov. Rick Scott signed SB 1096, which repealed some regulations based on the recommendations of a group of superintendents, including Montford. The bill repealed a requirement approved in 2010 that all public schools and universities gather and report statistics showing how much material each had recycled during the year. It also ended a 2002 requirement that schools submit plans for teaching foreign languages to kindergarteners.

Other efforts to ease the regulatory burden have targeted schools that meet certain conditions. Since 2017, schools with strong test scores and consistently high letter grades could be qualified as “Schools of Excellence,” which grants their leaders more flexibility.

Moore said he hopes things work out this time around, but said the key is allowing changes to apply across the board, not to certain schools or districts, and to carefully consider future regulations and their potential effects.