The Brennan Center has released projections of congressional reapportionment following the 2030 Census. The Brennan Center projects Florida and Texas to be the big winners, with each state gaining four (!) congressional seats. Arizona, Idaho, North Carolina, and Utah each gaining one seat in the projections. California loses four (!) seats, with New York losing two seats, Illinois, Minnesota, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island and Wisconsin project to lose one seat each.

Twelve congressional seats and electoral college votes changing hands, if it comes to pass, will be no small thing. Partisans ought not to get too excited yet, as it is quite possible that what constitutes a “swing state” might shift between now and 2032. Viewing this from where things sit at the start of 2025, however, these projections look broadly favorable to Republicans.

Part of the story reflects Florida's long-term rise and New York's long-term decline. Florida gaining seats and New York losing seats accelerate a century-long trend. The chart below uses the Brennan estimates for 2030 and shows the actual number of congressional seats for Florida and New York from 1930 to 2030.

It is not terribly difficult to discern the trends here, what with New York having nine times as many congressional seats as Florida in 1930 but projected to have eight seats fewer than Florida after 2030. As recently as 2000-2010, New York still held a 29 to 25 congressional seat advantage, and the states stood tied at 27 each for the 2010-2020 period. If the Brennan projections prove out, Florida will have gained five seats since the 2010 Census, while New York will have lost three.

Many factors are at play in these trends: weather, business climate, housing prices, taxes etc. California’s projected loss of four seats seems to indicate that policy-related factors can and have overwhelmed even the most favorable climate.

In the case of New York and Florida, Florida has a K-12 system that produces in many ways better results for a fraction of the cost. For the sake of brevity, I will not demonstrate this here, but feel free to visit the NAEP data explorer if you feel skeptical. New Yorkers have not only been surpassed by Florida, but taxpayers must foot a revenue per-pupil bill that is nearly three times higher than that in Florida.

Paying the nation’s highest state and local tax burden is voluntary; you can avoid it, for instance, by moving to Florida. Surveys further indicate that more than four times as many parents desire to enroll their children in private school as those that manage to do so (42% desiring it, 10% practicing.) Florida provides for families wishing to attend private schools. The state also provides a more effective and efficient public school system for those who do not.

This century-long trend may not reverse; it may accelerate.

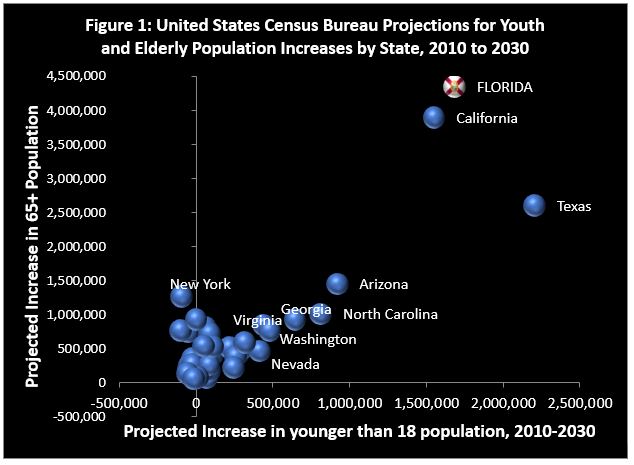

A few years back I visited these pages to discuss Florida’s age demographic change, and the challenges it will pose to policymakers, especially with regards to health care and education. Here’s the abridged version: Florida has lots of elderly people, and lots of young people, and relatively few working-age people paying for health care for the elderly and education for the young. This should not be terribly shocking if you have walked around a bit in Florida. The problem: demographers project Florida is growing large additional populations of elderly and young people. When you use Census projections to plot out all 50 states, it looks like: The Census Bureau made these projections some time ago and decided to leave the task of updating projections to the state. Fortunately, Florida’s Office of Economic and Demographic Research (EDR) has created updated age demography projections for the state. There’s good news and there’s bad news in the updated EDR projections. The good news: They aren’t as scary as the Census projections. The bad news: It’s not by much.

The Census Bureau made these projections some time ago and decided to leave the task of updating projections to the state. Fortunately, Florida’s Office of Economic and Demographic Research (EDR) has created updated age demography projections for the state. There’s good news and there’s bad news in the updated EDR projections. The good news: They aren’t as scary as the Census projections. The bad news: It’s not by much.

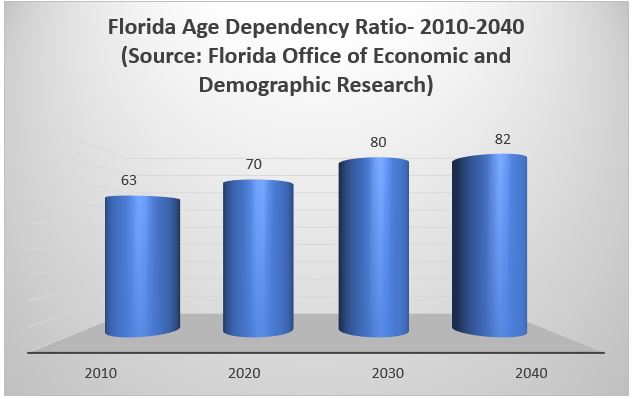

Demographers calculate an “age dependency ratio” as a measure of societal strain. To create an age dependency ratio, you take the under-18 population, add in the 65-and-older population, and then divide that sum by the number of 18- to 64-year-old people. Basically, what you are looking at is the ratio of people less likely to be in the workforce and more likely to be drawing on state services like K-12 education and Medicaid to those more likely to be in the workforce (and thus carrying the bulk of the burden for paying for things like education and health care services).

Here are the age dependency ratios for Florida in 2010, 2020, 2030 and 2040 based on EDR projections. Think of it this way: For every 100 working-age people pushing the cart of Florida’s social welfare state, how many elderly and young people do you have riding in the cart?

Four years from the time of this writing will mark the half-way mark for the massive Baby Boom generation reaching the age of 65. By 2030, all surviving Baby Boomers will have reached the age of 65. From a state budget perspective this is challenging on multiple fronts: retirees live on fixed incomes and have left their peak earning and taxpaying years behind. They also draw upon state health care benefits at a rate far above average.

Four years from the time of this writing will mark the half-way mark for the massive Baby Boom generation reaching the age of 65. By 2030, all surviving Baby Boomers will have reached the age of 65. From a state budget perspective this is challenging on multiple fronts: retirees live on fixed incomes and have left their peak earning and taxpaying years behind. They also draw upon state health care benefits at a rate far above average.

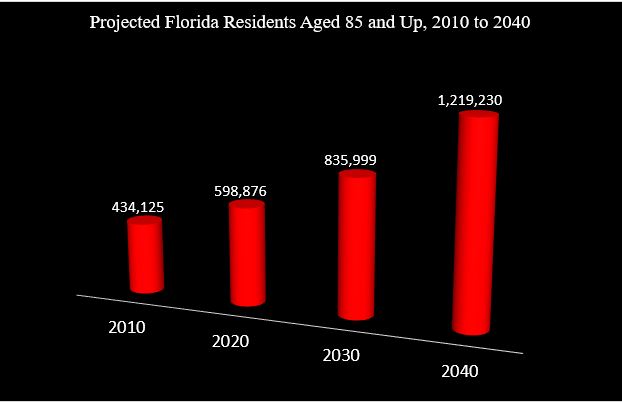

States like Florida and Arizona have an added wrinkle as retirement destinations. Incoming retirees provide a short-term economic boon to a state economy as they make some major purchases (like condos) but then they often live frugally. The state budgetary gain turns to pain with the “super elderly” aged 85+ who tend to draw mightily on state health care spending late in life. Below are the EDR projections for Florida residents age 85 and over.

Using 2010 as the baseline for comparison, that looks like an almost doubling by 2030 and a getting close to tripling by 2040. A fierce battle over limited state resources may loom: a generational battle between the old and the young, education spending versus health care spending.

Using 2010 as the baseline for comparison, that looks like an almost doubling by 2030 and a getting close to tripling by 2040. A fierce battle over limited state resources may loom: a generational battle between the old and the young, education spending versus health care spending.

We should all – left, right and center – seek to avoid such a clash. By far the best solution involves Florida developing a far more productive and innovative workforce to accompany far-reaching policy and medical innovations. Florida K-12 spending is enshrined in the state constitution and won’t be going anywhere, but the need to develop methods to better educate student at the same or lower costs will grow increasingly acute.

Absent substantial productivity/policy/medical innovation:

Many of the Florida taxpayers who will be tasked with paying for the pensions and health care expenses of the Baby Boom retirees of 2020, 2030 and 2040 sit in Florida’s classrooms right about now. Fortunately, there has been an enormous amount of progress made over the last two decades in Florida education, the subject of a forthcoming post.

The United States faces a staggering demographic challenge over the next two decades. Every state in the union faces this problem, and some have it harder than others. Florida faces one of the larger challenges in that the population of both young and old will be vastly increasing at the same time. This challenge will require fundamental rethinking of the social welfare state, including but not limited to K-12, higher education, pensions and health care.

The United States faces a staggering demographic challenge over the next two decades. Every state in the union faces this problem, and some have it harder than others. Florida faces one of the larger challenges in that the population of both young and old will be vastly increasing at the same time. This challenge will require fundamental rethinking of the social welfare state, including but not limited to K-12, higher education, pensions and health care.

The U.S. Census Bureau projects a substantial increase in the school-aged population in Florida (see Figure 1).

Of course, not all children under age 18 will be attending school in 2030 – most notably the children born in 2027 to 2030. So for a more precise measure of the school-aged population likely to be attending public school in 2030, we can consult a different set of Census estimates. This alternate data provides estimates on the population of 5- to 17-year-olds (see Figure 2). This substantially understates the likely size of Florida’s 2030 K-12 population, as it does not include 18-year-olds. The reader should also note the fact that 4-year-olds are eligible to receive public assistance for Voluntary Pre-K. Nevertheless, the same overall trend reveals itself: the Florida public school population is set to expand substantially.

Florida, in short, will need to find a way to educate far more than one million additional students each year by 2030. Note that Florida’s charter school law passed in 1996. The time between 1996 and now is the same at the amount of time between now and 2030. Charter schools educated 203,000 students in 2012-13.

The Step Up for Students and McKay programs educate another 86,000. It will take a very substantial improvement in Florida choice programs simply to get them to absorb a substantial minority of the increase in student population on the way. Otherwise, Florida districts will either find themselves overwhelmed with expensive construction projects, or can start using their facilities in early and late shifts, or both.

A giant new investment in school facilities will prove incredibly difficult because of the other meta-trend in Florida’s demographics: aging. The expansion of Florida’s youth population, while substantial, pales in comparison to that of the elderly population. Florida’s population aged 65 and older projects to more than double between 2010 and 2030, from approximately 3.4 million to almost 7.8 million (see Figure 3). (more…)