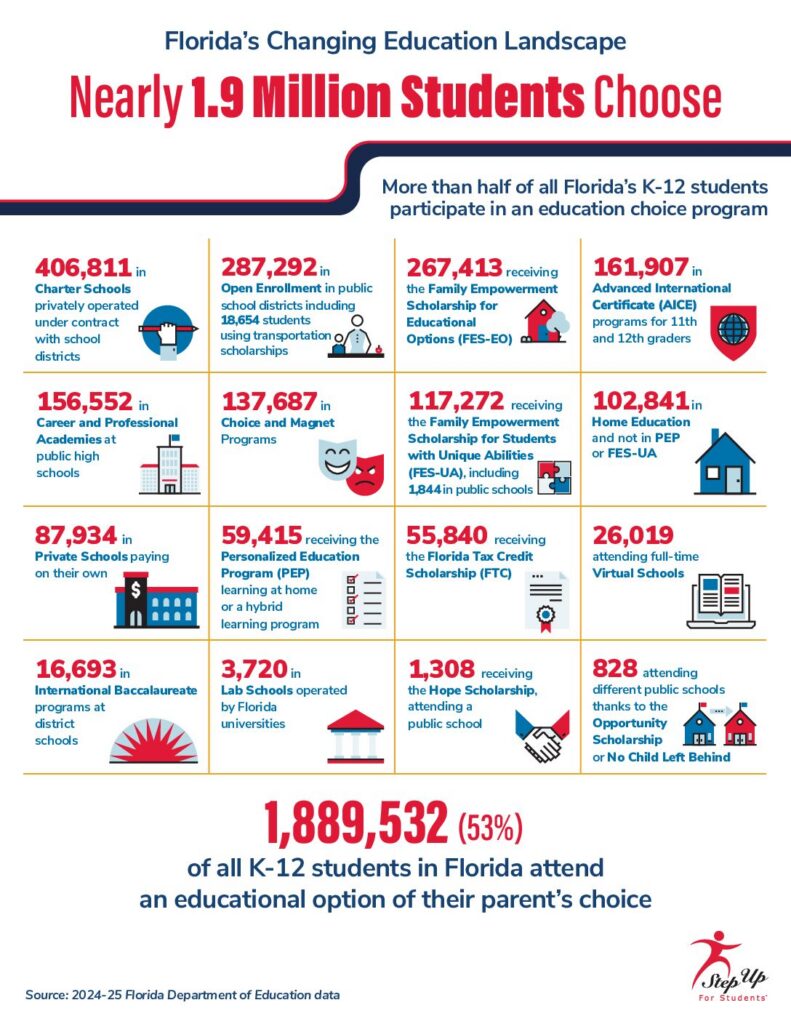

Florida’s K–12 education landscape continues to shift toward choice. During the 2024–25 school year, 53% of all K–12 students — 1,889,532 children — attended a public, private, or home education option of their parents’ or guardians’ choice. Just one year after crossing the 50% threshold for the first time, Florida’s school choice participation grew by nearly 100,000 additional students.

“Each year, Florida families have made it clear that they want more options for their children’s education,” said Gretchen Schoenhaar, CEO of Step Up For Students, the Florida non-profit that administers the state’s education choice scholarship programs.

“Increasingly, parents and guardians are willing to mix and match private and public resources to choose the ones that work best for their family.”

Since the 2008–09 school year, Step Up For Students, in collaboration with the Florida Department of Education, has tracked enrollment across a variety of choice programs. The 2023–24 school year represented a historic milestone: the first time more than half of all K–12 students in the state attended a school of choice. The 2024–25 school year continued that upward trend.

The Changing Landscapes report draws from Florida Department of Education data and removes, where possible, duplicate counts to provide a clearer picture of school choice participation. For example, it adjusts for home education students supported by the Family Empowerment Scholarship for Students with Unique Abilities (FES-UA) and eliminates double-counted students in career and professional programs. It also excludes prekindergarten students in FES-UA and programs such as Voluntary Pre-Kindergarten (VPK), as the report focuses solely on K–12 education.

While many families still choose their neighborhood public schools, Florida’s education system now offers a broad range of options to meet diverse student needs. As in past years, public school choice remains dominant, occupying four of the top five spots in overall enrollment. Charter schools are the most popular single option, followed by district open enrollment programs, the Family Empowerment Scholarship for Educational Options (FES-EO), career and professional academies, and Advanced International Certificate of Education (AICE) programs for upperclassmen.

The largest increases in enrollment occurred in the FES-EO program, which has merged with the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship program, and the Personalized Education Program (PEP), a scholarship that helps fund education at home.

Among public school options, AICE enrollment grew nearly 17%, career and professional academies grew 6.2%, and open enrollment grew 4.6%. While overall district enrollment appeared to decline slightly, these public school choice options still grew more than charter schools (independent public schools), which grew just 2.3%. This may suggest that school districts could benefit from expanding their own menu of diverse school options to better retain families.

Choice remains strong within Florida’s public school system. More than 1.2 million of the state’s 2.9 million public school students attended a school of choice, while another 688,000 students outside the public system enrolled in private schools or home education programs.

A newer option to keep an eye on is district schools offering classes and services to students on an education choice scholarship, paid for with their scholarship funds. Currently 37 of Florida’s 67 districts have been approved as providers with Step Up For Students, and another 11 are in the process of being approved. These arrangements further blur the line between public and private and emphasize that the focus remains on the individual needs of students.

With so many options available, Florida’s education system has entered a new phase. Choice is no longer an alternative; it is the norm. Families routinely evaluate multiple pathways, and whether they select a different option or remain in their assigned public school, they are making an active choice. The result is an education landscape in which public, private, and home education options coexist and evolve together, reflecting the reality that students and families have different needs, and that those differences matter.

A Tampa Bay area morning TV show kicked off National School Choice Week by highlighting a family who benefits from a state K-12 scholarship.

Arielle Frett appeared on Fox 13’s “Good Day Tampa Bay” program on Monday with her son, AnyJah, a ninth grader at The Way Christian Academy in Tampa. She said she moved to Florida from St. Thomas, Virgin Islands, in 2017 to find better educational opportunities for AnyJah, who has severe autism.

“No teachers were able to work with him on his level,” Frett told Fox 13 reporter Heather Healy. “Most of his learning in English and math are on fifth and sixth grade levels now.”

A U.S. military veteran and single mother of two, Frett said she would not have been able to afford a private school for her son without the scholarship.

She said AnyJah, who receives the Family Empowerment Scholarship for students with Unique Abilities, is “loved, protected, and thriving” at his school, where class sizes of 10 to 12 students allow for more individual attention. He can also receive his therapies during school.

The segment also featured information about Florida’s robust education choice options. Those include traditional public schools, district magnet schools, charter schools, private schools, microschools, homeschools, virtual schools, and customized education programs that allow parents to mix and match.

“We’ve gone from education and funding through the system to now empowering families by putting the money in their hands and allowing them to make the most appropriate educational decisions for families,” said Keith Jacobs, director of provider development at Step Up For Students, which administers most of the state’s education choice scholarships.

Jacobs has spent the past year working with school districts to provide individual courses to scholarship families whose students do not attend public or private school full time, paid for with scholarship funds. About 70% of Florida school districts are participating.

The scholarship application season for the 2026-27 school year begins Feb. 1. Visit Step Up For Students to learn more and apply.

During a 1916 football game between Georgia Tech and Cumberland, Georgia Tech coach John Heisman famously urged his players on to victory- “You're doing all right, team, we're ahead. But you just can't tell what those Cumberland players have up their sleeves. They may spring a surprise. Be alert, men! Hit 'em clean, but hit 'em hard!” Cumberland committed 15 turnovers in the game and had one of their players getting tackled for a six-yard loss on an attempt at an offensive rush declared their “play of the game.” Georgia Tech won the game 222 to 0.

This story has repeatedly come to mind repeatedly over the last decade while reading stories about the competition between surging Florida and floundering New York.

The New York Post reports that New York City Schools will spend $42,000 per student this year. Spending $840,000 on a classroom of 20 fourth graders might seem a bit pricey, especially given that judging on their 2024 NAEP performance, nine of them will be reading at “below basic.” New Yorkers must pay sky-high taxes to support the world’s most expensive illiteracy generator/job programs, which is one of the reasons so many New Yorkers keep becoming Floridians. Now, however, it isn’t just people and companies migrating from New York to Florida; New York’s Success Academy schools are also heading south.

Through the wizardry of Stanford’s Educational Opportunity Project graph generator, I’ve placed New York Success Academies (Marked 1-7) in the graph for the overall state of Florida for academic proficiency. Schools are dots; green dots are higher than average, blue below average, etc.

You don’t see many high-poverty schools (graph runs from low poverty on the right to high poverty on the left) with students scoring 3ish grade levels above average, but that is exactly what Success Academy has consistently delivered in New York.

Being a rational human, you might think that New York policymakers would be falling over themselves to get as many Success Academies operating as possible, but that is just you being silly again. New York lawmakers maintain a statewide cap on the number of charter schools. Apparently, New York lawmakers feel the need to keep safe from, well, learning.

Florida, on the other hand, does not have a cap on charter schools. Rather than treating highly successful schools specializing in educating disadvantaged students as a public menace, Florida is rolling out the red carpet for highly effective school models. Success Academy plans to open 40 schools in Florida over the next 10 years, something which New York law prohibits.

Is it too much? Too much winning? No, Florida, you have to win more! Or to paraphrase Coach Heisman “You're doing all right, Florida; you’re ahead. But you just can't tell what those New Yorkers have up their sleeves. They may spring a surprise. Be alert, men! Hit 'em clean, but hit 'em hard!” Capitalizing on the abject folly of New York policymakers is hitting both clean and hard.

Markala was Marlena and John Roland’s first child, and there were more on the way – four more, in all. And Markala was 5, so the Roland children were going to reach school age in quick succession.

This presented a dilemma.

“We wanted our kids in private school, but we didn’t have the money,” Marlena said.

But there was hope.

The year was 2005, and Marlena, a teacher at a private school near their Coral Springs home at the time, learned about a private school scholarship that had been established a few years earlier and was managed by Step Up For Students.

For nearly 20 years, a member of the Roland family attended a private school with the help of a scholarship managed by Step Up For Students.

She applied and was accepted, and for nearly all of the next 20 years, at least one of the Roland children attended a private school with the help of a Step Up scholarship. The exception was the two years the family lived in Georgia.

“It was a blessing for us,” John said. “The best thing we did was give them that education foundation.”

“None of that would have been possible without the scholarship,” Markala said.

Marlena was a teacher at ALCA when the kids began school. Even with the employee discount, she said the cost of tuition would strain the family’s finances. Still, she wanted her children to benefit from ALCA’s educational setting just like the students she was teaching.

“We wanted to set the bar high, to create good study skills and habits. We wanted them to be well-rounded,” said Marlena, who also taught at The Randazzo School for nearly 10 years, including the time Marcia attended.

Marcia, who graduated last May from The Randazzo School, was the last of the Roland children to use a scholarship managed by Step Up For Students.

It was by design that the Roland children split their education between private and district schools. Some were sports-related, but mostly, John wanted their children to experience both educational settings.

“John said, ‘Let’s put them in public school for a little bit and see how it goes,’” Marlena said. “He said they need to have both, and that will build character and build them as individuals.”

And it worked.

The private school experience helped the children excel at their district schools.

“It laid a really good foundation for us,” Markala said. “Just getting us excited to be in the classroom, to learn new things, to collaborate with others.

“I had friends (in high school) ask me, ‘Where did you learn this? Why are you thinking that way?’ All I could say was, ‘Thanks to my teachers at ALCA and Westminster.’ They really set us apart and prepared us for what was coming next. We were leaps and bounds ahead of our peers.”

John credited the private school education his children received but also gave credit to the emphasis he and Marlena placed on education at home.

“When I dropped them off at school, I told them we’ll add to it when you get home,” he said.

“They didn’t play with that,” Markala said. “That was non-negotiable in our house.”

She remembers a time when John sold the family pickup truck to help meet the expenses of her attending Westminster that the scholarship didn’t cover.

“As a kid, you see them doing that, and I'm like, ‘Don't we need that car to get places?’ They really valued education. That was what was important,” she said. “I see that now as an adult, the things that they're willing to do to make sure that we had a good education, putting us into spaces where we could learn and grow have been tremendous to me, even now that I’m in the workforce.”

Kate Payne of the Associated Press wrote a piece about the Madison County School District, a small rural area east of Tallahassee  titled School choice and a history of segregation collide as one Florida county shutters its rural schools.

titled School choice and a history of segregation collide as one Florida county shutters its rural schools.

Madison is closing three low-enrollment schools. Of course, people don’t like closing schools. Of course, the choice programs make for a ready scapegoat for district officials seeking to shift blame, but maybe journalists should thoroughly investigate alternative explanations.

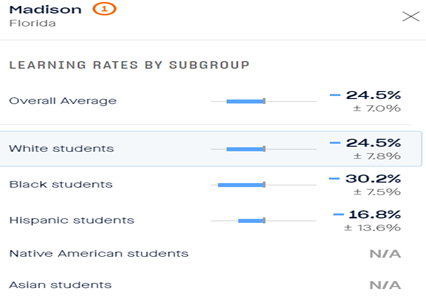

Below, for example, is a chart from the Stanford Educational Opportunity Project demonstrating the overall learning rates for Madison students in grades three through eight from 2008 through 2019, and by student racial/ethnic subgroup:

Unlike academic proficiency rates, academic growth is not strongly correlated with student demographics. An academic growth rate of 0 would indicate students learned a year’s worth of math and reading on average per year. Sadly, Madison students score less than zero, a good deal less. In other words, families have had plenty of reasons to avoid enrolling their children in Madison.

Moreover, the net impact of the school consolidations will be to bring a bit of integration into a school district with high levels of segregation. If the choice programs played a major role in the closure of the three Madison schools, the choice programs would have promoted integration within the traditionally segregated district. The district plans to consolidate the three under-enrolled schools with another district school with a 70% Black student school majority. Black students make up a minority of the three closing schools, meaning the consolidated school would move to 58% Black.

Alas, however, Florida’s choice programs cannot take much credit. Step Up for Students’ own Scott Kent set the record straight in another story regarding the Madison consolidation

Scott Kent, a spokesperson for the organization, said there are only 166 students in the district participating in the program. Since Florida enacted one of the largest private school voucher expansions in the nation in 2023, only 47 additional students signed on to the voucher program, according to Kent, who added that only seven of those students transferred from a district public school.

For the record, the district undoubtedly should have consolidated these schools many years ago, and the seven students transferring out of the district with a scholarship represent a tiny fraction of the district’s enrollment. Madison County Superintendent Shirley Joseph noted that the consolidation will save the district millions of dollars, which it can use to improve teacher pay. Given the district’s dire need for higher quality instruction and learning, this sounds like it could be a splendid outcome.

The Payne article however ends in this fashion:

There's always talk about leaving the public schools, Joseph said, but she believes most families will stay. In the meantime, she’s focused on delivering the best education possible for the students she has — the ones who can’t leave.

A focus on academic achievement would be a welcome change if they manage to pull it off. In the meantime, we should celebrate rather than lament the fact that every single Madison student can leave. If they make the most of freedom, Madison educators will create enough of their own schools to encourage more overdue rational decision making and further district integration.

Welcome to life with liberated families, Madison. Delightfully, there’s no turning back.

A provision that made Florida a national literacy leader 20 years ago could be repealed in an effort to ease the regulatory burden on Florida’s school districts.

A provision that made Florida a national literacy leader 20 years ago could be repealed in an effort to ease the regulatory burden on Florida’s school districts.

A state Senate panel unveiled a package of proposed deregulation legislation. One proposal would end the requirement that public schools hold back third graders who struggle in reading.

House Bill 1, passed earlier this year, created the largest expansion of education choice in the nation’s history.

The legislation also launched a new deregulation effort, championed by Senate President Kathleen Passidomo, designed to create a more level playing field for school districts. The Senate Education Committee this week reviewed survey responses from more than 2,000 people, most of them parents.

Right now, public schools are required to hold back third graders who score below Level 2 on state reading assessments. Students can still move on to fourth grade if they pass an alternative test, present a portfolio of work, or meet specific exemptions.

The Senate proposal would eliminate those provisions and require school districts to provide “specific supports” for students in kindergarten through third grade who are retained because of a reading deficiency.

Other proposals would overhaul the A-F grading formula, ease the state-mandated turnaround timeline for low-performing public schools, and eliminate must-pass math and English exams for 10th graders.

State Sen. Corey Simon

Sen. Corey Simon, R-Tallahassee, and two other senators overseeing the deregulation project did not comment on the proposed legislation, which was outlined at a Senate K-12 Education Committee workshop this week, as well as a separate list of recommendations from the Florida Department of Education that did not include eliminating the retention requirement or other major shakeups of the state accountability system.

Adam Miller, a senior chancellor at the Florida Department of Education, said learning to read well by third grade is critical to success in future grades.

“If we are pushing kids into fourth grade, not only are they struggling in social studies, they struggling in science, and they’re struggling in math, and we’re just putting them on a bad path forward,” Miller told members of the House Education Quality Subcommittee while presenting the department’s recommendations.

A key part of then-Gov. Jeb Bush’s education reform policies, third-grade retention sparked plenty of controversy, with critics saying it would harm children socially and emotionally.

Since it was enacted, Florida’s national reading scores have improved, and about half the nation’s states have adopted similar policies.

As Bush remarked in 2018, “It’s absolutely insidious to suggest that a functionally illiterate kid going from third grade, it’s OK to go to fourth. Really?”

During 2003-04, the initial year of the policy, the state retained 14% of third graders. Six years later, that number dropped 6% as more students met the standard. Martin West, a Harvard Graduate School of Education professor, and other researchers followed 75,000 Florida students who were held back under the law and compared them with students who were near the cutoff score and were promoted as well as classmates now in the same grade as those who were retained. The study showed higher test scores in high school and students taking fewer remedial courses, with no effect on their probability of graduating from high school.

While research on retention policies has shown that middle school retention can raise high school dropout rates, holding younger students back while providing support such as summer school and personalized literacy plans can help them make academic progress.

The proposals from the Florida Department of Education and all three senators will be included in bills to be discussed during the committee’s next meeting on Nov. 15.

Former state Sent. Bill Montford, who is also chief executive officer of the Florida Association of District School Superintendents, praised the deregulation efforts as “music to the ears’ of those who work in district schools.

“Now is the time to make those bold and sometimes controversial decisions that will ensure a level playing field for all choices that parents and students will have,” Montford told the committee “Our traditional neighborhood schools have proven for generations to be highly successful, and the preferred choice of most families, and your efforts can make traditional schools an even better choice for our parents and our students.”

My new year’s resolution is to do a better job explaining myself as a choice supporter. There is apparently a need for this, as evidenced by this recent Tampa Bay Times editorial piece about key players in Tallahassee in 2019. Regarding Florida’s new education commissioner, the Times opined:

Richard Corcoran

The answer to every education conundrum in Florida is not either (a) charter schools or (b) vouchers. In fact, new Education Commissioner Richard Corcoran should remember most students attend traditional public schools, that the state Constitution guarantees a “high quality system of free public schools,” and that his first order of business should be strengthening those schools, not scheming to tear them down or replace them.

This statement could be critiqued in a variety of ways, but today I’ll attempt to demonstrate that expanding educational opportunities however represents a strategy to in fact achieve a “high quality system of free public schools.” Furthermore, it seems to be working.

Florida created the nation’s first choice program for students with disabilities in 1999 with the McKay Scholarship Program. Students with disabilities have had the option of applying for a scholarship to attend a different public or private school statewide since 2001. Rather than representing a scheme to “tear down or replace” public schools, the statewide performance for students with disabilities improved faster than the national average. Florida lawmakers (wisely) further expanded options for students with disabilities in 2015 by creating the Gardiner Scholarship Program-the nation’s second Education Savings Account program.

This seems to be working out relatively well for Florida students with disabilities, the vast majority of whom continue to attend district schools. For you incurable skeptics, things pretty much look like Florida and the 49 dwarves when it considering both gains and overall scores for students with disabilities:

And reading:

Students with disabilities in Florida public schools have had access to full state funded choice since 2001. Students with disabilities have also had access to the other forms of choice-charter schools, the Florida Virtual School, that all Florida students can access, but in addition to that, they have had the option of attending a private school with the state money following the child. The Florida tax credit program provides opportunities for low-income students but is limited by the amount of funds raised and has a waitlist. Florida’s students with disabilities have had the most robust set of choice options for the longest period.

When we compare the gains of student with disabilities (and the fullest access to choice programs) to students without disabilities on all the NAEP exams given consistently since 2003 it looks like this:

Ten points approximately equals an average grade level worth of progress on these NAEP exams (for instance we’d expect a group of 9th graders to do 10 points better than they had as 8th graders). The technical term to describe those red columns: HUGE! In fact, if Florida’s statewide gains had matched those of students with disabilities since 2003, Florida would have matched or beat NAEP champion Massachusetts on all four NAEP exams in 2017.

Impossible you say? Many would have said those academic gains for students with disabilities were impossible in 2003, nevertheless they happened.

“Pacific Rim” is without a doubt the greatest “giant robots smashing giant monsters” movie in the long and storied history of cinema. Okay, so the only real competition was the wretched “Pacific Rim 2” and maybe a few Japanese movies with people wearing rubber suits stomping on model buildings. Honest Trailers described “Pacific Rim” as either “The Most Awesome Dumb Movie of All Time” or “the Dumbest Awesome Movie of All Time.” “Pacific Rim” did indeed have everything your inner 9-year-old craves, including the above “Today we are cancelling the Apocalypse!” speech from the great Idris Elba.

So anyhoo – when do we get to cancel the apocalypse talk with regards to Florida schools?

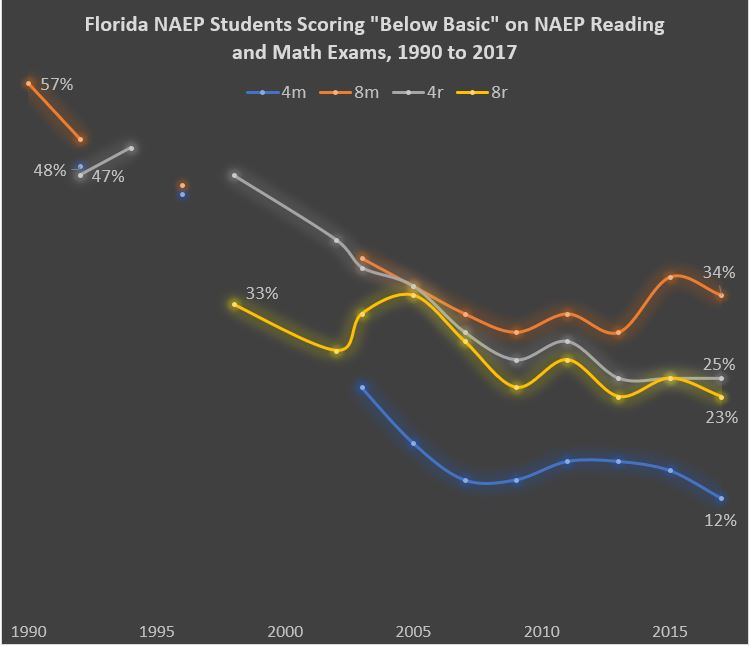

I first started following the K-12 debate in Florida back in the late 1990s. Then, sadly as now, the air was filled with claims about the “destruction of the Florida public school system.” Among the many problems with this fevered story is the fact that the Florida Constitution guarantees public school funding and the public supports that guarantee. A quick perusal of the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) – the most highly respected source of apples-to-apples K-12 data available, shows consistent improvement in outcomes over time. The below chart shows the percentage of Florida students scoring “Basic or Better” (top four lines) and “Proficient or Better” (bottom four lines) from the earliest available results (1990) to the most recent (2017). Note that all the lines are trending up – which in this case is what you want.

The trend in Florida students scoring “Below Basic” is easier to follow. “Below Basic” is the lowest achievement level on NAEP, so what you want to see in this next graph is the numbers trending down. Sure enough:

There are of course things to disagree over and debate, but for those liberally pushing Florida K-12 apocalypse narratives, I simply want to pose the following questions: How do you square this obvious evidence of academic improvement among Florida students with impending predictions of doom? Is there a nefarious plot to improve public schools to death? The comment section awaits. I’ll hang up and listen.

There are of course things to disagree over and debate, but for those liberally pushing Florida K-12 apocalypse narratives, I simply want to pose the following questions: How do you square this obvious evidence of academic improvement among Florida students with impending predictions of doom? Is there a nefarious plot to improve public schools to death? The comment section awaits. I’ll hang up and listen.

Florida schools are being demonized for student SAT performance. But when making an apples-to-apples comparison, controlling for racial and income differences between states - the results do not match the rhetoric.

Routinely underappreciated, Florida’s K-12 schools do outstanding work with what they are given. Despite a relatively large low-income/working-class majority-minority student population and low per-pupil funding compared to other states, Florida performs about middle of the pack on national assessments.

Results look even better when making apples-to-apples comparisons, which include controlling for racial and income differences between states. Unfortunately, that good news is often ignored by many professing anxiety over education quality in the Sunshine State.

The latest concern over the quality focuses on college readiness, specifically SAT scores, and suffers from a flawed apples-to-oranges comparison. (more…)

A new analysis by Reason magazine of Florida's public education system shows that, when focused on actual academic outcomes, the rhetoric of the system being in crisis again does not match the reality.

Is Florida’s public education system as bad as many of its critics suggest? Yet another analysis, focused exclusively on actual academic outcomes, says no. In fact, according to Reason magazine, Florida ranks No. 3 in K-12 educational quality and No. 1 in educational efficiency.

Released this week, Reason’s ranking based on outcomes isn’t that far off from Education Week’s ranking based on outcomes. Last month, Education Week ranked Florida No. 4 in the nation in “K-12 Achievement.”

Reason’s ranking relied on reading, math and science scores from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), also called “The Nation’s Report Card.” Education Week’s achievement ranking is based on NAEP reading and math scores; results on Advanced Placement exams; and graduation rates.

Education Week ranks states on three categories: “Chance For Success,” “School Finance,” and “K-12 Achievement.” These categories are compiled to produce an overall ranking. While Florida ranks No. 4 on K-12 Achievement, according to Education Week, the inclusion of the other categories drops the Sunshine State’s overall ranking to No. 29.

Other outlets, like U.S. News, also use data besides academic outcomes to determine rankings. The Reason study’s authors, Stan Liebowitz and Matthew L. Kelly, are not fans of this approach. They’re also not fans of using raw NAEP data without consideration for racial demographics, which they call “misleading.”

The combined methodological flaws lead to questionable, if not misleading, overall rankings, they write. (more…)