Kansas Gov. Laura Kelly in May signed House Bill 2567, which will allow the state’s students, including those presently attending in the Shawnee Mission School District (pictured above) to attend any public school district in the state as long as the school has space beginning in June 2024.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Jeff Murray, formerly employed at School Choice Ohio and the Greater Columbus Arts Council, appeared today on the Fordham Institute’s website.

What parents are looking for in an ideal school choice scenario is often very different from what they settle for in the real world. Cost, distance, academic quality, safety, extracurricular options, and a host of other factors are all at play, meaning trade-offs are unavoidable.

Recently published research findings try to capture the matrix of compromises being made. Data come from Kansas City, Missouri, from fall 2016 to spring 2017.

School options were widespread in the city, including intradistrict opt-in among all 26 of Kansas City Public Schools’ general education buildings and nine magnet schools, along with 20 public charter schools and 24 private schools.

At the time of the study, more than 8,500 students (23% of all K–12 students) attended private schools, over 6,500 students (18%) attended charters, and more than 4,100 (11%) attended magnets. Around 70% of the remaining students attending general education KCPS buildings opted for a school outside their neighborhood assignment zone.

Aiding parents in their choices: a single application for any KCPS building, including magnets, and a second single application that covered nearly all of the city’s charters.

The Kansas City Area Education Research Consortium recruited parents through multiple avenues in 2016 and 2017 to answer survey questions regarding school preferences. The sample comprised 436 individuals, proportionally representing district attendance zones, racial makeup of the population, and socioeconomic distribution around the city.

Approximately 33% of respondents had a college degree. While no breakdown exists for how many students attended which school type, all types were represented.

Respondents were first asked to rate, on a scale of one to five, how important each of 19 school attributes was to them in choosing a school for their oldest child. Attributes included academic performance, afterschool programs, teacher and student diversity, curriculum, facilities, leadership, parent involvement, and safety.

Most importantly, respondents were asked to rate their preferences “in the context of an ideal world where they were not bound by social, economic, or logistical constraints and concerns.” They were then asked to choose their top three based on their current real-world circumstances and with “personal constraints,” as well as any “systemic obstacles” they have encountered in mind.

Finally, they were asked to rate on a scale from one to five how satisfied they were with their child’s school, and, on a reverse scale, to what extent their child’s school “[fell] short in things that would otherwise make a difference” in their education.

So how far was the ideal from the reality? It depended on the family. No one got everything they wanted because everyone’s ideal ratings put almost every school feature at the top of the list. While teacher quality was highest and social/medical services lowest, there were less than 1.5 ratings points separating them (4.82 out of five vs. 3.37) and all 17 other features were crammed in between.

Parents who were white, who had any education level above high school, and earned over $50,000 per year were more likely to rank their child’s school very highly on their top three attributes than were their peers, marking what the researchers deem a state of lowest “preference compromise.” That is, their children were more likely to attend schools in the real world that ranked highly on the attributes that mattered most to them in an ideal condition.

Parents outside those demographic categories were more likely to report attending schools where their highest-rated attributes are not present or present at a lower level than their peers, indicating a less-than-ideal choice. Hispanic parents were most likely to report compromising on their highest-rated attributes, with Black parents close behind.

Parental satisfaction scores track with level of compromise—the bigger the gap between ideal attributes and real experience, the lower the reported satisfaction level. The researchers thus concluded that these families are least well-served by school choice in Kansas City, but that leap owes more to the ideal than to the real.

On the upside here, all families’ preferences were considered equal in the analysis, with no leeway to consider that parents with lower education or income levels might lack knowledge of important school attributes or available options. This is extremely positive and a better approach than many previous such studies.

On the downside, the methodology assumes that all parents have already chosen—and are reporting their satisfaction with—their best possible option. This is nominally true, but the universe of options for a family with one working parent and two cars is likely to be different—and much larger in the real world—than for a family with two working parents and a single vehicle, even if their incomes are the same and even if they live in the same zip code.

Given modern residential patterns and school zone boundaries’ correlation with historic redlining efforts, the gap between the ideal and the real is already baked into school choice infrastructure in many cities—especially for families with fewer resources. It is true that lower-income families or Hispanic families have less access to school choice, but the researchers’ conclusion that such a fact renders school choice problematic does not logically follow.

While not giving more families a free ticket into the ideal school of their dreams, KC did offer a fairly robust choice environment in 2017. The sheer number of students attending non-assigned district schools at the time is evidence enough of that.

A majority of parents—from all walks of life—likely found for their children a choice they liked better than they would if they had been forced to send their child to their zoned school with no alternatives. And that’s a win.

Chester E. Finn Jr., distinguished senior fellow and president emeritus at the Fordham Institute, authored what is in my opinion the K-12 commentary of the year thus far with Did public education have it coming?

Chester E. Finn Jr., distinguished senior fellow and president emeritus at the Fordham Institute, authored what is in my opinion the K-12 commentary of the year thus far with Did public education have it coming?

Finn’s piece was a reaction to Laura Meckler’s column in the Washington Post titled, “Public education is facing a crisis of epic proportions.” The article, all too common in education journalism, focuses on the concerns of the suppliers of public education.

Alternatively, Finn asks the question: What might the situation look like if we focused on the consumers of public education? He writes:

The schools our kids attended were closed so long that students lost whole years of learning. Those from families with limited means lost even more. Those schools were closed far longer than they needed to be, apparently because the adults who work in them didn’t want (or were scared) to return, and those running them put their employees’ interests ahead of those of their students and parents. We watched the firemen and nurses and utility workers keep coming to work despite the pandemic. Why not the teachers?

Worse, the closed schools’ failure to supply satisfactory forms of remote instruction meant that millions of children forgot how to study, how to get along with other kids, how to relate to grown-ups outside their families. Idleness, lassitude, and frustration took a toll of their physical and mental health and made life extremely difficult for us parents and other caregivers, including messing up our own work lives.

Many of us had no choice but to quit our jobs. No wonder many of us took education into our own hands, seeking out other schools that managed to stay open, getting serious about homeschooling, hiring tutors when we could afford it, and teaming up with neighbors to create quasi-schools. Yes, we’re angry, furious even, and yes, our kids are upset and acting out.

And it didn’t get any better when we got them back into school only to discover that, instead of the Three R’s, our schools were obsessing over racial and political issues. No wonder we’re protesting at school board meetings. No wonder a bunch of politicians are using our unhappiness to get themselves elected. And it’s no help at all when folks in Washington seem more interested in sending money and coddling misbehavers than in whether our children are learning.

To all this, I say, YOMP!

Andrew Rotherham, co-founder and partner at Bellwether Education Partners, also turned in a thoughtful take on the Meckler piece, writing for Eduwonk.com, asking: Is the sky really falling? Rotherham makes a number of valid points, one of which I broadly agree with, that public education, at least in the role of being a source for adult employment, is not at any existential risk. Far from it in fact.

State constitutions still guarantee K-12 funding after all, and we have numerous examples of per-pupil funding increasing despite shrinking public school systems. Rotherham’s list of challenges, however, is lengthy, and these challenges all have worsened simultaneously. What’s more, some of the larger challenges didn’t make Andy’s list.

Based on international exams of academic achievement, we can say that before the pandemic, America’s public schools provided an unremarkable education to affluent kids at high costs. For the less-advantaged student, these schools provided a very low-quality education at high costs. Efforts to change this situation met with fierce resistance, and not only from unionized employee interests preferring the status-quo. Suburban complacency represented a separate challenge.

Post-pandemic, we find ourselves in an altered political scene. Suburban complacency is gone for the reasons cited by Finn. Black families are homeschooling like nobody’s business, as are others. District officials are gasping for air beneath piles of temporary federal dollars that they can’t quite figure out how to spend, while buses go without drivers, special needs students go without helpers, classrooms go without substitutes.

It’s not like these sorts of things go unnoticed; a growing number of families feel they no longer can rely upon school districts.

An unforeseen baby-bust broke out in 2007, and social distancing did not help matters. A school culture war has broken out and looks to rage on indefinitely. Ten thousand baby boomers continue to reach the age of 65 daily and will be competing for the public resources used to inflate per-pupil spending. The massive daily drip of such retirements apparently will be accompanied by background music featuring endless cultural conflict over schools.

But is the sky actually falling? No.

American K-12 is a complete bureaucratized and politicized mess with very real victims. What we should do with the time given to us is push forward to reshape American K-12 education with widely shared values: pluralism, liberalism, and tolerance. We need more effective and more cost-effective school models and methods of education.

Plodding bureaucracies overseen by boards elected in ultra-low turnout elections dominated by incumbent interests (strangely enough) were not ideal for producing such things. We still need them, so let’s get on with it.

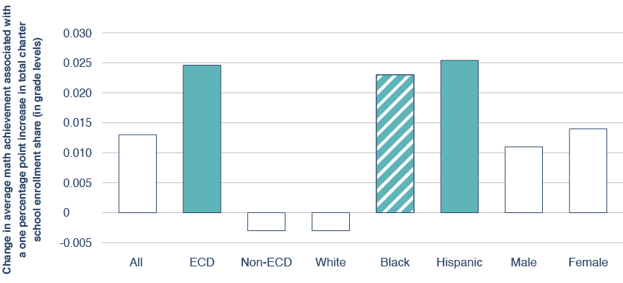

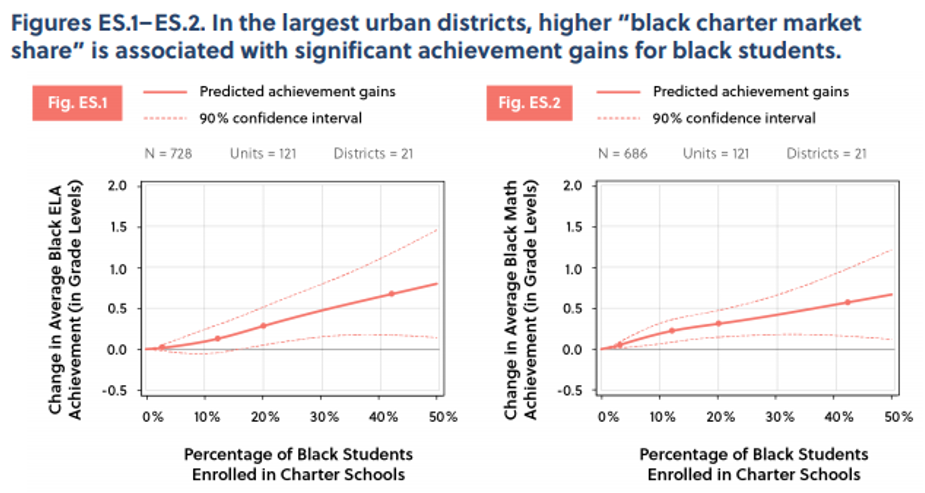

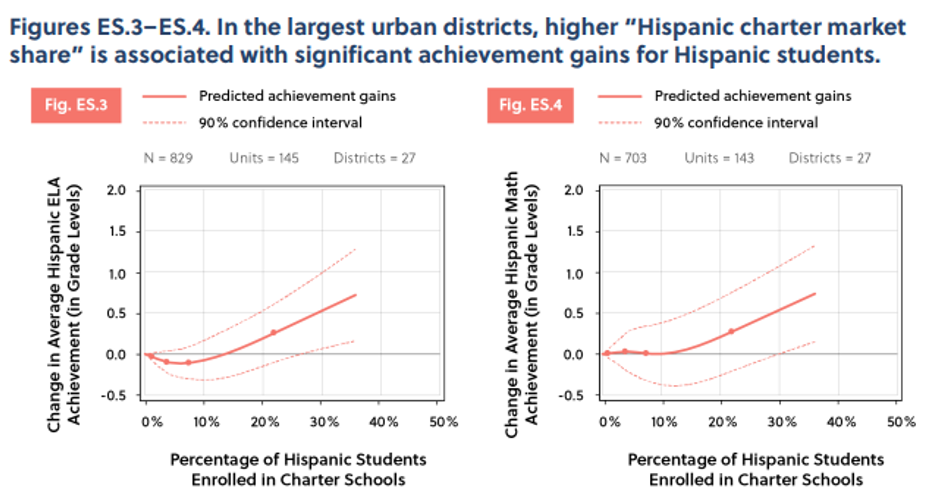

![]() Making use of data from the Educational Opportunity Project at Stanford University, the Fordham Institute has produced a new study of metropolitan area academic achievement. Fordham finds that increased charter school market share is associated with statistically significantly higher scores for disadvantaged student populations.

Making use of data from the Educational Opportunity Project at Stanford University, the Fordham Institute has produced a new study of metropolitan area academic achievement. Fordham finds that increased charter school market share is associated with statistically significantly higher scores for disadvantaged student populations.

The chart below shows differences for math achievement for economically disadvantaged and Hispanic students as significant at the .05 level, and the difference for Black students significant at the .1 level.

The study also found evidence of narrowing achievement gaps in metropolitan areas with larger charter school shares in math, as evidenced below.

The Fordham findings are consistent with a great many studies that have found positive competitive effects associated with choice programs. The benefits are not limited to charter schools. Similar findings have been found with regard to private choice, and for areas with higher levels of choice between district schools.

Choice programs, rather than existing in silos, interact with each other. Charter and private choice programs create incentives for districts to open their doors for open enrollment. Once one district lowers the open enrollment drawbridge, nearby districts feel an increased pressure to follow-suit, and the competitive juices begin to flow.

The Ohio Senate’s education plan for the state budget for 2022–23 would prioritize families’ needs and wants.

Editor’s note: this commentary from Aaron Churchill, the Ohio director for the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, appeared recently on the Institute’s website.

Across the nation, state lawmakers have been heeding the call for parents to have more control over their children’s education.

Recognizing that there is no “one-size-fits-all” model that meets every kid’s need, legislators have been actively strengthening school-choice policies and expanding options for families. Florida, for instance, recently expanded its nation-leading private school scholarship programs. Iowa just significantly improved its charter school law. West Virginia and Kentucky created brand-new educational savings account (ESA) programs that offer parents flexibility in how they meet (and pay for) their kids’ educational needs.

So far this year, Ohio’s education debates have paid scant attention to choice. Lawmakers have focused on technical issues with the school funding formula and overall spending levels. But that changed last week with the unveiling of the Senate’s education plan for the state budget for the fiscal years 2022–23 (HB 110). If enacted, its proposals would be a huge step forward in putting families’ needs and wants at the center of education policy. Here are highlights of the Senate approach:

Removes caps on the number of EdChoice scholarships available. EdChoice, the largest of Ohio’s scholarship programs, allows children from low- and middle-income households to attend private schools of their choice. The program has grown significantly over the past decade, but legislators have limited the number of available scholarships, which in the past has left some children in the lurch. The Senate plan would ensure that any eligible student applying for an EdChoice scholarship receives one.

Increases the EdChoice and Cleveland scholarship amounts. The EdChoice and Cleveland scholarship amounts have fallen well behind public school spending. Today, they’re worth just $4,650 in grades K–8 and $6,000 in grades 9–12, even as Ohio’s public schools spend on average $14,000 per pupil. The Senate plan narrows that gap somewhat by lifting these scholarship amounts to $5,500 and $7,500 in grades K–8 and 9–12, respectively. Importantly, it also ensures that in future budgets, scholarship amounts will automatically rise in proportion to any increase in public schools’ base funding. This provision would create more predictability and fairness for families that rely on these programs.

To continue reading, click here.

![]() For more than a decade, the Thomas B. Fordham Institute has hosted a weekly podcast, the Education Gadfly Show. On this week’s episode, Step Up For Students president Doug Tuthill joins Mike Petrilli, the Fordham Institute’s president and a research fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution, and David Griffith, a senior research and policy associate at the Fordham Institute, to discuss the potential impact of, and lessons learned, from Florida’s new school choice expansion in a segment titled, “Hooray for Florida’s new school choice legislation.”

For more than a decade, the Thomas B. Fordham Institute has hosted a weekly podcast, the Education Gadfly Show. On this week’s episode, Step Up For Students president Doug Tuthill joins Mike Petrilli, the Fordham Institute’s president and a research fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution, and David Griffith, a senior research and policy associate at the Fordham Institute, to discuss the potential impact of, and lessons learned, from Florida’s new school choice expansion in a segment titled, “Hooray for Florida’s new school choice legislation.”

Here’s a taste of what you’ll hear from Tuthill as he reflects on the landmark expansion of education choice in Florida.

“I think the Legislature said, ‘Okay, it’s time to grow up. We can integrate these programs, make them more simple and more elegant, easier for families to access,' and that’s the big message in this bill. It significantly improved access. Over 1 million students were added to the eligibility through this program. The legislation dramatically expands the number of children who have access.”

“These programs have been islands. We’ve now integrated them into the funding system of the state of the normal public education funding mechanism. What you’re really seeing is a simplification over time, making them more user friendly, and sort of a normalization. It’s now a normal part of public education … It’s now normal in Florida.”

“We wanted to make sure no families are left out. Our philosophy has never been that only some kids deserve access to the school that best meets their needs … We’ve never been a pro-private school choice organization. We’ve always been a pro-education choice organization … When we find families who are being priced out or locked out, we try to reduce those barriers to maximize access for every family and every child.”

You can listen to the podcast here.

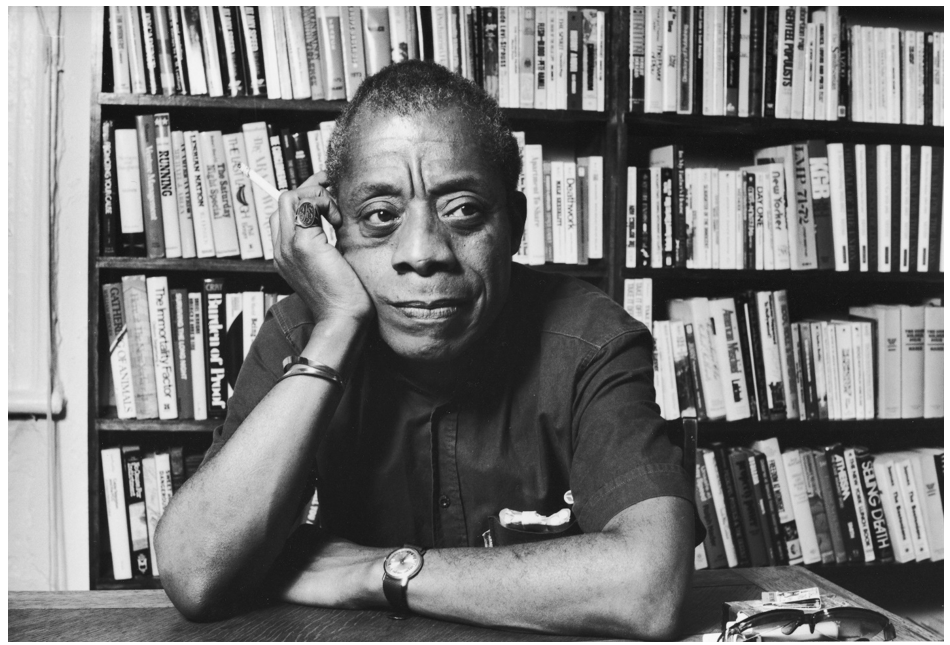

James Arthur Baldwin was an American novelist, playwright, essayist, poet and activist. His essays, as collected in Notes of a Native Son (1955), explore intricacies of racial, sexual, and class distinctions in Western society, most notably in regard to the mid-20th century.

“You were born where you were born and faced the future you faced because you were black and for no other reason,” James Baldwin wrote to his nephew James in 1962.

“The limits to your ambition were thus expected to be settled. You were born into a society which spelled out with brutal clarity and in as many ways as possible that you were a worthless human being. You were not expected to aspire to excellence. You were expected to make peace with mediocrity. Wherever you have turned, James, in your short time on this earth you have been told where you could go and what you could do and how you could do it, where you could live and whom you could marry.”

Nearly 58 years have passed since Baldwin wrote those words. How much has changed?

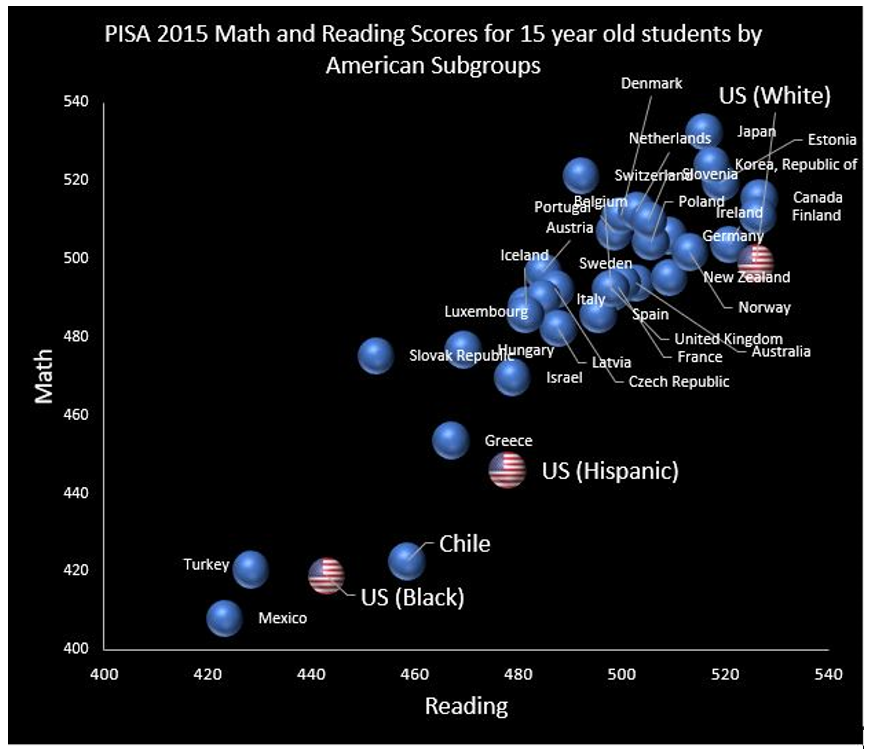

Are Black students still “not expected to aspire to excellence” and to “make peace with mediocrity?” Look at the PISA math and reading exam results and judge for yourself:

Are people still telling Black students “where you could go and what you could do?” Ask Kelly William-Bolar, a Black mom who spent time in jail for sending her children to a better-performing public school in Ohio. Read the Newsday investigation regarding the continuing role of race, income and real estate in segregating families by school.

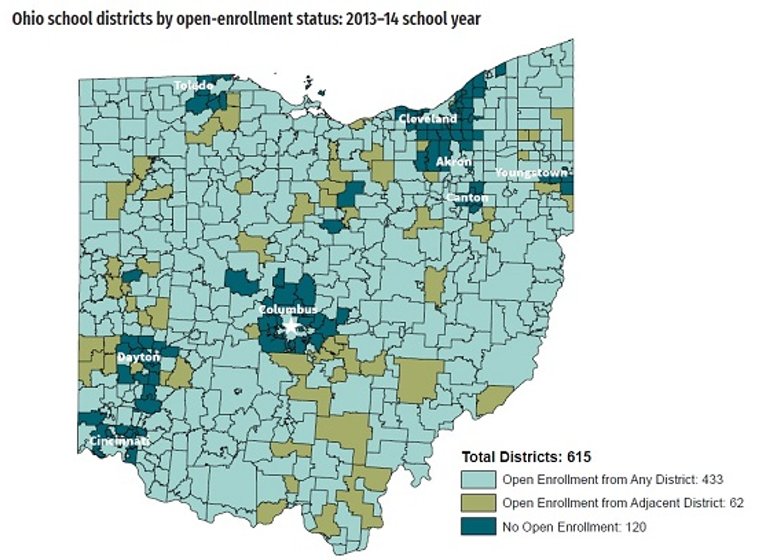

Or look at the report published by the Fordham Institute on interdistrict open enrollment in Ohio, a first-of-its-kind analysis conducted by researchers at Ohio State University and the University of Oklahoma. See any suburban districts volunteering to take urban kids through open enrollment transfers?

Me neither, which leads inevitably to the conclusion that Kelly William-Bolar’s case was anything but a fluke, that those lines were working exactly as intended, and still do today.

Hundreds of thousands of students, many of them students of color, sit on private choice and charter waitlists. Anti-choice interests not only shamelessly do whatever they can to keep those families waiting, but they also sometimes mumble about segregation in a theoretical fashion, attempting to justify their actions. The gigantic and all-too-real sort of segregation on display in the map above does not ever seem to merit their attention.

“The purpose of education,” Baldwin wrote “…is to create in a person the ability to look at the world for himself, to make his own decisions.”

The time is long past for families to make their own decisions about where and how their children will be educated.

Forget about the charter vs. district school debate. The more important question is whether student achievement improves overall. Does a rising tide of charter school enrollment lift the overall achievement boat? The Fordham Institute released a report to address exactly that.

Forget about the charter vs. district school debate. The more important question is whether student achievement improves overall. Does a rising tide of charter school enrollment lift the overall achievement boat? The Fordham Institute released a report to address exactly that.

As charter school enrollment increases as a percentage of the total students within a district (called “market share” by the report’s authors), the achievement gains of all students, within both charter and district, improve. According to the report, urban areas with high concentrations of black and Hispanic enrollment in charter schools saw significant math and reading achievement gains for black and Hispanic students overall.

Note: Figures show the predicted changes in the average ELA and math achievement of grades 3-8 black students in charter and traditional public schools as district-by-grade-level charter market share increases among black students. Estimates were generated using a cubic spline with knots at the 5th, 35th and 95th percentiles (see red dots) and controlling for student demographics, district-by-grade-level unit and year fixed-effects, and district-specific quadratic time-trends. Sample includes all urban units with a 0 to 50 percent black charter market share and average black enrollment >2,500 between 2009 and 2015.

Note: Figures show the predicted changes in the average ELA and math achievement of grades 3-8 Hispanic students in charter and traditional public schools as district-by-grade-level charter market share increases among Hispanic students. Estimates were generated using a cubic spline with knots at the 5th, 35th and 95th percentiles (see red dots) and controlling for student demographics, district-by-grade-level unit and year fixed-effects, and district-specific quadratic time-trends. Sample includes all urban units with a 0 to 35 percent Hispanic charter market share and average Hispanic enrollment >2,500 between 2009 and 2015.

Hispanic students benefit in suburban and rural areas, while black students see achievement gains in rural areas, but not suburban ones. White students see no gains regardless of the location of the charter school or district.

“Increasing the percentage of black and Hispanic students who enroll in charters — especially in the largest urban districts, which educate millions of minority students per year — would significantly reduce the longstanding racial achievement gaps that are ostensibly of concern to policymakers,” the authors wrote.

These are striking results, especially given the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People’s call for a moratorium on charter schools. National teacher unions, which represent a mostly white teaching corps and also oppose charter schools, have been longstanding financial supporters of the civil rights group.

Fordham’s study is not without its limitations. The dataset covers seven years, the research is not randomized, and the results may be due to the fact that charter schools are disproportionately established within low-performing urban districts to begin with.

Still, author David Griffith notes that his report “is consistent with prior research that suggests black and Hispanic students learn more in charter schools, and that competition from charter schools has a positive, or at worst neutral, effect on traditional public schools.”

Two new studies illuminate Florida K-12 funding. The first, from Mike Petrilli, president of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute and research fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution, includes this chart:

So, for those of you squinting at your iPhone, the east-west axis is tracking the percent change in enrollment between 2000 and 2015, while the north-south axis is showing the constant dollar percentage increase in per pupil funding.

There obviously is a negative relationship between rapid enrollment growth and high levels of per pupil spending growth. Most of the states with very large increases saw their student population shrink. Florida looks to have seen population growth of approximately 15 percent during this period and per pupil funding growth of 18 percent.

Petrilli notes a national baby-bust, but in Florida this may simply mean a moderating of enrollment growth, already noted between older Census estimates and more recent state projections. There will be no moderation of the increase in the elderly population. A decade from now this may look like the good ole days of funding increases, so buckle up.

TaxWatch also released a study finding an “all in” per pupil number for Florida schools of $10,856. The analysis compared the traditional district school cost to the cost of two of the largest learning options the state currently provides to parents and their students – charter schools and tax-credit scholarships.

TaxWatch estimated per charter school student funding for fiscal year 2017-18 to be $7,476. The average maximum scholarship available through the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship Program, which allows children from low-income and middle-income families to attend private schools, for fiscal year 2017-18 was $6,447.

A Florida newspaper editorial board that recently editorialized that Florida “could not afford” vouchers may require some remedial math; Florida has a great deal of enrollment growth on the way and can more easily afford to choose charter and private schools than districts, although all three will remain options.

Imagine if parents could pick and choose individual courses for their children, from an endless array of different providers, in the same way they now pick and choose other products online. Michael Brickman, the national policy analyst for the Fordham Institute, says that world may not too far in the future, thanks to a budding parental choice trend folks are calling “course choice.”

“Ideally parents and students can sit down at the computer and "shop" online for courses,” Brickman said during a live chat Wednesday with redefinED. “This is so commonplace and mundane when we go on sites like Amazon.com and add items from different sellers from around the world to our virtual shopping cart. Hopefully through (course choice), education can catch up to the rest of the world in this regard.”

A handful of states are moving ahead with course choice, including Louisiana and Wisconsin, where Brickman served as a policy advisor in Gov. Scott Walker’s office before joining Fordham. Florida is among those taking a close look. Brickman recently authored a policy brief that gives education officials a primer on course choice and the challenges ahead.

Course choice is complementary to parental choice options such as charter schools and vouchers, he said during the chat. But it can spur those options to innovate even more.

“I love traditional school choice and think it's nowhere near obsolete as of now,” he said in response to a question. “But one of the frustrating things about these reforms is how similar the schools look to one another. The point of additional flexibility is to INNOVATE. Some charter and private models are off and running with this but many are still lining up 30 desks in each room, putting a teacher in front of the class for 7 hours a day, etc.”

You can read the entirety of the chat in the transcript below.

Things are changing so fast with parental choice, charter schools and vouchers are starting to look old school. Before you know it, a lot more parents won’t just be choosing schools for their children, they’ll be choosing individual courses.

It’s called course choice. And to help us all get a better handle on it, we’re having a live chat next week with Michael Brickman, national policy director for the Fordham Institute. Brickman authored an excellent primer on course choice that Fordham released last week.

The chat is open to anyone with a fair question. It’s in writing, so we’ll type in questions, you’ll type in questions and our guest will type in answers as fast as his fingers can fly.

To participate, just come back to the blog on Wednesday, May 28. We’ll start promptly at 11 a.m. Just click in to the live chat program, which you’ll find here on the blog.

In the meantime, if you have questions that you’d like to send in advance, you can leave them here in the comments section, email them to rmatus@sufs.org, tweet them to @redefinEDonline and/or post them on our facebook page. See you then!