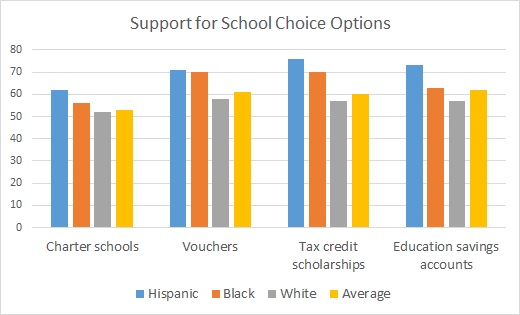

A Friedman Foundation survey shows Hispanics are among the strongest supporters of various school choice options. Note: The survey has a 3.1 percent margin of error, which was larger for subgroups. More methodological details can be found here.

Hispanics strongly support privately operated school choice options, at rates higher than the national average for all groups, according to the results of a new national survey released today.

Hispanic backing for school choice programs exceeds the national average for charter schools, vouchers, tax credit scholarships and education savings accounts, found the survey, which was funded and sponsored by the pro-school-choice Friedman Foundation.

Sixty-two percent of Hispanic respondents favor charter schools, compared to 56 percent of African-Americans and 52 percent of whites. Seventy-one percent favor vouchers. Seventy-three percent favor education savings accounts.

Hispanic support was strongest for tax credit scholarships, with 76 percent in favor and 16 percent opposed. The national split was 60 percent in favor and 29 percent opposed.

The findings are another example of the disconnect between popular support for choice programs and the political divisions that dog them. Other surveys have also found particularly strong support for choice programs in minority communities, even as those communities are disproportionately represented by Democratic lawmakers who are more likely than Republicans to oppose them. (more…)

This is the second post in our series on the Voucher Left.

Way back in 1978, when Bee Gees ruled the radio and kids dumped pinball for Space Invaders, a couple of liberal Berkeley law professors were promoting a variation on “universal” school vouchers that they believed would ensure equity for the poor. Along the way, they foreshadowed a revolutionary twist on parental choice that would make national headlines nearly four decades later.

John E. “Jack” Coons and Stephen Sugarman didn’t use the term “education savings accounts” in their book, “Education by Choice.” But they described a sweeping plan for publicly funded scholarships in terms familiar to those keeping tabs on ESAs. They envisioned parents, including low-income parents, having the power to create “personally tailored education” for their children, using “divisible educational experiences.”

John E. “Jack” Coons and Stephen Sugarman didn’t use the term “education savings accounts” in their book, “Education by Choice.” But they described a sweeping plan for publicly funded scholarships in terms familiar to those keeping tabs on ESAs. They envisioned parents, including low-income parents, having the power to create “personally tailored education” for their children, using “divisible educational experiences.”

To us, a more attractive idea is matching up a child and a series of individual instructors who operate independently from one another. Studying reading in the morning at Ms. Kay’s house, spending two afternoons a week learning a foreign language in Mr. Buxbaum’s electronic laboratory, and going on nature walks and playing tennis the other afternoons under the direction of Mr. Phillips could be a rich package for a ten-year-old. Aside from the educational broker or clearing house which, for a small fee (payable out of the grant to the family), would link these teachers and children, Kay, Buxbaum, and Phillips need have no organizational ties with one another. Nor would all children studying with Kay need to spend time with Buxbaum and Phillips; instead some would do math with Mr. Feller or animal care with Mr. Vetter.

Coons and Sugarman were talking about education, not just schools, in a way that makes more sense every day. They wanted parents in the driver’s seat. They expected a less restricted market to spawn new models. In “Education by Choice,” they suggest “living-room schools,” “minischools” and “schools without buildings at all.” They describe “educational parks” where small providers could congregate and “have the advantage of some economies of scale without the disadvantages of organizational hierarchy.” They even float the idea of a “mobile school.” Their prescience is remarkable, given that these are among the models ESA supporters envision today.

It's also noteworthy given a rush to portray education savings accounts as right-wing.

In June, for example, the Washington Post described the creation of the near-universal ESA in Nevada as a “breakthrough for conservatives.” School choice would likely be a top issue in the 2016 presidential campaign, the story continued, with leading Republicans like Jeb Bush, Scott Walker and Marco Rubio all big voucher supporters and Democratic front-runner Hillary Clinton opposed. The story pointed out Milton Friedman’s conceptualizing of vouchers in 1955, then added, “The idea was long thought to be moribund but came roaring back to life in 2010 in states where Republicans took legislative control.”

It’s true that in Nevada, Republicans took control of the legislative and executive branches in 2014, and then went on to create ESAs. But it’s also true that across the country, expansion of educational choice has been steadily growing for years, and becoming increasingly bipartisan in a back-to-the-future kind of way. Nearly half the Democrats in the Florida Legislature voted for a massive expansion of that state’s tax credit scholarship program in 2010. About a fourth of the Democrats in the Louisiana Legislature voted for creation of that state’s voucher program in 2012. New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo has been fighting for a tax credit scholarship in that bluest of blue states – an effort in which he’s joined not only by many other elected Democrats, but by a long list of labor unions.

These Democrats are sometimes accused of being sellouts – often by teachers unions and their supporters, who have been especially critical of Cuomo. But the truth is, they can draw on a rich history of support for educational choice grounded in the principles of the American left.

The recent history of ESAs isn’t quite as polarizing as the Post suggests, either. (more…)