Editor’s note: Policy expert and redefinED guest blogger Jonathan Butcher wrote this commentary for the Goldwater Institute. It appeared June 18 on the institute’s blog, In Defense of Liberty.

Editor’s note: Policy expert and redefinED guest blogger Jonathan Butcher wrote this commentary for the Goldwater Institute. It appeared June 18 on the institute’s blog, In Defense of Liberty.

As students around the country begin summer break, the status of K-12 school operations is different from state to state—even district to district in some places. Here’s what parents need to know:

Reopenings have started.

Lawmakers in Montana and Wyoming have allowed school buildings to reopen (some schools are currently holding in-person classes). In Illinois, Pennsylvania, and Texas, school buildings are open for summer school. Last week, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis released a plan to reopen schools in August at full capacity.

These decisions should be made as locally as possible. Federal guidance from the Centers for Disease Control will be broad and cautious, not specifically tailored to meet the needs of every school. The national perspective offers general guidelines, but state and district officials must evaluate local needs.

Parents may not send students back.

Surveys indicate parents are still concerned about the pandemic and school officials’ choices in the face of changing conditions. Between 40 and 60 percent of parents have said they are considering homeschooling in the fall. These numbers should be a sign to district administrators that were slow to provide any instruction between March and May that they need to restore parents’ confidence in their child’s school.

Some districts and charter schools, in particular, moved quickly to provide remote learning, but reports reveal that thousands of students in large cities never interacted with teachers. School district officials in Fairfax County, Virginia, prepared no virtual instruction, while district administrators in Pennsylvania, told teachers not to help any students online until the district approved the activity. Meanwhile, students across Detroit and Los Angeles did not touch school assignments during the quarantine.

Parents and students need stability. Officials need to tell parents they are preparing now to reopen at full capacity, barring local COVID-19 outbreaks. Educators should also tell families they will evaluate students at the beginning of the semester to determine where students stand academically.

State and district policymakers and special interest groups such as teacher unions are demanding more money from Washington before schools reopen, but they should be concerned first with regaining parents’ trust. The financial recession will impact all schools, likely prompting school administrators to lobby for spending increases. These officials must demonstrate now that they are putting student needs first—students that have already missed months of instruction.

Private schools are important parts of their communities, and they are suffering.

Private schools are a lifeline to 5.7 million students around the country, but the pandemic and ensuing recession are forcing them to close—permanently—by the dozen. (The Cato Institute is tracking the closings.) Federal spending is not a trust fund to rescue schools. For public and private schools, such spending expands federal influence, which will come back to haunt these communities when federal lawmakers decide standard operational requirements such as testing and admissions criteria are in order.

State lawmakers can help by creating new opportunities for students that want to access private schools, such as Utah’s new scholarships for children with special needs or a proposal in North Carolina to provide scholarships to students from families that received federal relief payments at the pandemic’s outset. Broad eligibility is essential.

Meanwhile, U.S. Department of Education guidance says districts should use federal relief spending on services for K-12 schools to help all private school students in low-income areas. Again, better to not expect federal assistance, but if the resources are already being disbursed, the spending should help all students.

Some public-school officials are resisting, but if a private school closes and parents decide to homeschool, even under difficult conditions, public schools have a tough sell at the ballot box. Traditional schools should not miss an opportunity to demonstrate how valuable their services can be.

Public and private school students, especially those struggling to keep up, cannot afford to lose another semester. The lesson from the Pandemic Spring is that we cannot wait for the virus to disappear before we start living again.

Benjamin Franklin Academy in Salt Lake City is an assistance program to homeschooled children with special needs.

Around the country, talk of closures and quarantine is giving way to plans for re-opening. Despite moving in fits and starts, Utah officials found something unique for families and students to look forward to even if schools are closed for the rest of the year.

On Friday, state lawmakers approved a proposal to provide flexible learning scholarships to children with special needs. The Utah account-style scholarships combine the features of what are commonly known as tax-credit scholarships (like Florida’s scholarships for children from low-income families) and education savings accounts, as found in Arizona, Florida, Mississippi, North Carolina, and Tennessee.

Individuals and corporations will receive a dollar-for-dollar tax credit for donations to scholarship account-granting organizations. The scholarship organizations will use the contributions to award accounts to students. Parents can use a scholarship account to find educational therapists that meet a child’s unique needs, buy textbooks, and pay tuition at a private school or for online classes, to name a few possible uses.

Utah’s new scholarship offers families and students multiple private learning options, similar to education savings accounts. By funding the accounts through charitable contributions, Utah officials connected the scholarships with the private choices of businesses and other donors.

In 2016, Jason Bedrick, now policy director at EdChoice, Clint Bolick, former Goldwater Institute vice president and current Arizona Supreme Court Justice, and I described how such an arrangement could work in our research for the Cato Institute. We wrote, “Tax credits simply leave money in the hands of taxpayers who are free to choose which scholarship organizations to support with their own money,” and by adding the savings account component to the scholarships, Utah families can challenge their students or otherwise design a learning experience for a student.

Utah’s scholarship accounts followed a winding path to approval. Gov. Gary Herbert vetoed the proposal near the end of the legislative session, suggesting the scholarships would require new taxpayer spending. State analysts, however, had already reported that every child that leaves a public school to use a scholarship would save the state $1,871. While estimates were not available for existing homeschool or private school students, children with special needs often require expensive interventions no matter their school or learning routine.

With a global financial crisis settling in, lawmakers everywhere should be looking for effective, cost-saving ideas. The scholarships will be worth different amounts based on a family’s income, similar to K-12 private school scholarships available in Indiana. Utah children from families with income levels at or below 185 percent of the federal poverty line will receive scholarships worth approximately $9,000 per year, according to Utah Policy, while students from wealthier families will receive scholarships worth between $5,000 and $7,000, depending on a family’s income.

States around the country need innovation such as this. Before the pandemic, families of children with special needs were already aware of the kinds of products and assistance their children need to be successful and, if possible, learn to be independent. But during the recent shutdowns, meeting the needs of children diagnosed on the autism spectrum or living with Down syndrome presented a challenge to parents and educators. Families using accounts in North Carolina and Arizona have reported that they can continue many services for their children because the accounts are so versatile. Families of these children celebrate when their students make progress and are justifiably fearful those improvements will be lost when normal routines are interrupted.

Utah’s scholarships will be active in January 2021, which gives officials time to sort out some of the features clearly available to children using education savings accounts, such as the ability to save money from one year to the next to prepare for future expenses. Utah policymakers should look to the states with accounts to find answers to common questions about how students can access more than one product or service.

Good ideas like this have a way of breaking through, despite a governor’s veto pen. And this one arrived just in time for Utah families who are ready for life after the pandemic.

You, dear reader, look as though you could use some distraction from the viral apocalypse. Like many good stories, this one flashes back to the past to inform the present.

You, dear reader, look as though you could use some distraction from the viral apocalypse. Like many good stories, this one flashes back to the past to inform the present.

A decade ago, while an analyst at the Goldwater Institute, I participated in a debate concerning choice versus curriculum reform. Yes, people were confused about whether those things were mutually exclusive a decade ago, as they are today. (Spoiler alert: choice helps curriculum reform).

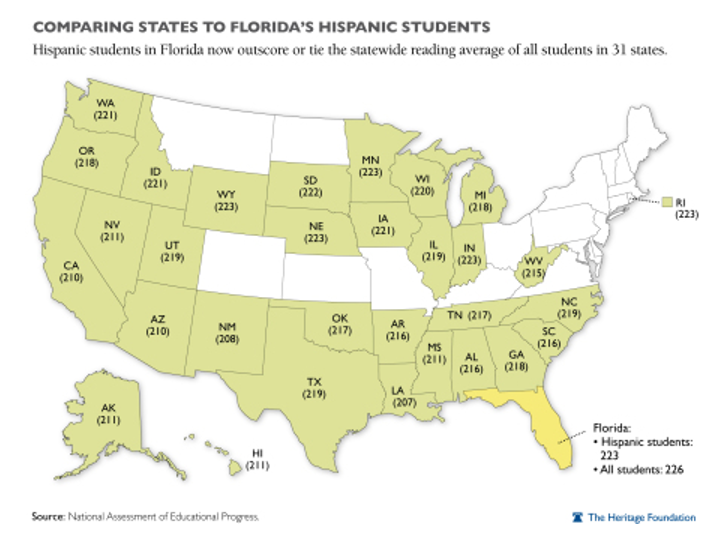

In any case, the debate prompted me to ask myself which states had done a lot of both choice and testing accountability. This in turn led me to look closely at the NAEP scores of Florida and to consider that former Gov. Jeb Bush had aggressively sought to improve literacy instruction by creating a variety of public and private choice mechanisms.

Staring at fourth-grade NAEP scores by race/ethnicity on my computer screen, here is what I discovered.

The conversation around K-12 in Arizona at the time frequently involved an “if you control for student demographics, we are kind of average” story. This was part of a fable with a thousand faces; you will hear different versions of it in different states. In Arizona, the story involved kids immigrating from Mexico who were unable to read Spanish. In Minnesota, I’ve heard tales told in hushed voices about Hmong kids. In more than one southern state, I’ve heard allusions to scores of white kids scoring quite high when they weren’t anything of the sort. The details vary, but the moral is always the same: “We here in state X, we’ve got the really hard-to-educate kids.”

The fact that Florida’s Hispanic students were reading approximately a grade level higher than the average for all students in Arizona required the development of a new rationale. That new rationale was the magic Cuban theory. Florida’s Hispanics are Cubans, the story went, and they are wealthy. “Obviously we can’t expect to do that with our Hispanic students,” the theory concluded.

I related the magic Cuban theory to an audience at the first ExcelinEd conference held in Orlando. Given the advantage of local knowledge held by many audience members, the crowd laughed out loud at the absurdity of the stereotype. Despite living in a distant patch of cactus, I had spent enough time in the Florida Keys with my grandfather to develop a lifelong taste for ropas viejas and to know better.

The magic Cuban theory could never survive scrutiny. First off, Florida’s Hispanic community is vastly more diverse than appreciated by distant stereotypes, with Cubans constituting a minority among Hispanics. Second, Florida saw large increases in literacy among multiple ethnic groups. Magic Haitian theory anyone?

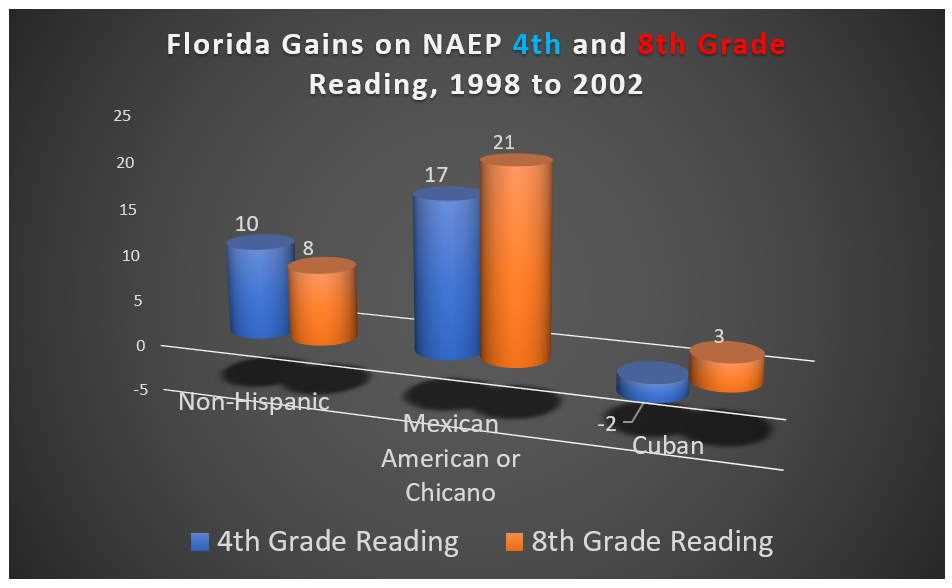

Finally, buried deep in the data explorer, NAEP has a variable that allows you to break down Hispanics by subgroup. NAEP, alas, discontinued this variable, but we do have it for both 1998 (the year before Jeb Bush took office) and 2002. It would have been great to have data from additional years, but note that the 2002 NAEP came before the adoption of the third-grade retention policy. Between 1998 and 2002, Florida policymakers had adopted major education reforms, but not all the reforms.

Here is what the gains looked like during the 1998 to 2002 period.

Florida’s Cuban-Americans scored well, but they were not driving gains. As a rough rule of thumb, 10 points on NAEP exams approximately equals an average grade level’s worth of progress. In other words, we would expect a group of fifth-graders given the fourth-grade test to do about 10 points better. The Mexican-American gains were very large, very meaningful and very statistically significant.

By the way, those eighth-graders from 2002 are approaching their mid-30s now. With all of today’s troubles, and considering those around the bend, Florida chose wisely in not succumbing to the soft bigotry of low expectations, instead making an all-out effort to teach literacy. Life is hard, but life is really hard if you can’t read.

Coronavirus is interrupting life in general and education specifically. As parents in the U.S. adjust to school closures and the potential for their K-12 child’s coursework to continue online, families should come to realize that they will be exposed to more of what their children are learning.

Coronavirus is interrupting life in general and education specifically. As parents in the U.S. adjust to school closures and the potential for their K-12 child’s coursework to continue online, families should come to realize that they will be exposed to more of what their children are learning.

For some, this will be new.

Wall Street Journal editor Serena Ng wrote recently from Hong Kong, where schools have been closed since Feb. 3, that she now can “see every detail of every lesson.” Ng says, “I previously had only a vague idea about what they were learning in school.”

All parents should be able to know what their children are learning, and for those paying attention in the coming weeks, the virus offers a chance for them to do just that. Working parents who juggle jobs and their children’s school activities while managing a home haven’t been neglectful if they don’t know what happened in fourth-period math on a given day (try asking a teenager what happened in class). Some simply have relied on schools to decide on instruction.

For others, this focus on content has been there all along.

March 2-4, the Institute for Classical Education and the Great Hearts Foundation held the National Classical Education Symposium, an event featuring sessions on teaching the Great Books, from “The Confessions of St. Augustine” to “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.” Great Hearts’ charter schools, which started in Arizona and have expanded to Texas, base their curriculum on these works. (You can find a complete list of the books students will be studying here.)

School districts are not always so transparent. As Matt Beienburg at the Goldwater Institute explained earlier this year, even if state law allows parents to review their child’s curriculum, they can do so only on school premises; in some cases and in some districts, there are limits set on when parents can see the material. Again, parents are not lazy if they don’t always know what is in their child’s syllabus.

When parents know what is being taught, they can effectively advocate for meaningful change. The reading wars over phonics versus whole language instruction are still with us today, while the Common Core debates over a national curriculum have simmered in time for everyone to scrutinize the New York Times’ 1619 Project.

The Project, a set of essays accompanied by K-12 curricular materials, “aims to reframe the country’s history by placing the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of our national narrative.” Slavery and the racism that followed are a blight on our nation’s past, but the Times has taken the idea too far according to many scholars. Pulitzer Prize-winning historians, leading intellectuals and even the Times’ own fact-checkers have criticized the essays, citing inaccuracies.

For thousands of parents, the initiative is not just a problem for someone else’s school. The Times and the Pulitzer Center have successfully advocated for integrating the material into some of the nation’s largest and most-high profile school systems, including Chicago, Newark, Buffalo and Washington, D.C. In Florida, Florida A&M University highlighted the Project in September 2019 and has hosted events on the topic with Florida State University.

Critically, the Times on March 11 issued a correction to a central premise of the essays, saying that not all colonial revolutionaries fought the British to protect the institution of slavery. If the Times heeds other warnings from experts, this modest correction should not be the last. Meanwhile, the Times already has disseminated the original curricular materials to schools.

Developments like these are among the many reasons why the next few weeks of school closures and online instruction are an important opportunity for parents to catch up on what is happening at their child’s school. When parents send children back to brick-and-mortar schools, they should do so ready to raise questions, prepared with more information.

Parents practicing “social distancing” in the coming weeks should use this period to get closer to their child’s school assignments.

For as long as there have been public schools, there has been school choice. That was the message Matt Ladner delivered to education choice critics in an interview on KJZZ, a Phoenix-based public radio station.

For as long as there have been public schools, there has been school choice. That was the message Matt Ladner delivered to education choice critics in an interview on KJZZ, a Phoenix-based public radio station.

The station aired interviews this week reflecting both sides of the education choice issue, which has been hotly debated in Ladner’s home state of Arizona. The first featured Diane Ravitch, an education professor, author and former assistant U.S. secretary of education during the George H.W. Bush administration. Ravitch argued that public schools are being hurt by billionaires who champion school choice.

Ladner, former vice president of research at the Goldwater Institute who is presently serving as director of the Center for Student Opportunity at the Arizona Charter Schools Association, responded in a follow-up interview today that education choice is not the result of a sinister plot but rather an attempt to democratize educational opportunities. School choice has always existed, he said, for those who are able to buy homes in well-to-do neighborhoods or afford tuition at pricey private schools.

“As long as school choice was tied to granite countertops, everything was fine,” Ladner said. “What we’re trying to do is extend that same opportunity to all students.”

Click here to listen to a snippet of the interview with Ravitch followed by Ladner’s interview.

Florida's Senate Education Committee just passed a plan that would make a voucher or other money for educational expenses universally accessible to Florida families. Despite its "vouchers-for-all" moniker, the proposed bill creating Education Savings Accounts passed with the support of one Democrat, Bill Montford, who also serves as the chief executive of the Florida Association of District School Superintendents.

"I've got some serious concerns," Montford said. "But this concept is certainly worth exploring."

The support is all the more notable considering Gov. Rick Scott himself backed away from the idea before the state's legislative session began last month. Scott's education transition team recommended the savings account, inspired by the Goldwater Institute, and proposed funding each participating family with an amount equal to 90 percent of what the state would pay per pupil in public schools. A torrent of criticism followed, even from those who favored vouchers in various designs, including from Cato Institute scholar Andrew J. Coulson.

The current plan would pay an amount only equivalent to 40 percent of the per-pupil allocation and there would be no income restriction on eligibility. The account could be used for educational expenses that include private school tuition, private tutoring, textbooks or college savings plans.