David Brooks has a piece in the Atlantic called How the Ivy League Broke America: The meritocracy isn’t working We need something new that is generating a lot of discussion. Brooks recounts the history of how selective American universities transformed from seeing good breeding Episcopalian standing as proper criteria for admission to one based upon meritocracy. Of course, we all like meritocracy in theory, but Brooks makes the case that in practice focusing on things like SAT scores tends to reduce people to a single attribute, which can and has been manipulated. Brooks moves on to proposed remedies that come across as both fuzzy and problematic, but his critique of the Ivy League and similar universities (henceforth Ivy+) certainly stings, although perhaps not as much as it could.

Before discussing the Brooks piece further, you should go read Andy Smarick’s delightful critique of the Brooks hypothesis, which argues that the Ivy+ is not so much destructive as it is overrated. Smarick’s takedown is both insightful and hilarious, but toward the end might begin to argue against the piece’s own hypothesis:

As a columnist for the NY Times, he’s surrounded by other columnists who have undergrad and/or grad degrees from Ivy+ schools: Douthat (Harvard), Dowd (Columbia), Edsall (Brown), French (Harvard Law), Kristoff ((Harvard), Krugman (Yale, MIT), Leonhardt (Yale), and Stephens (Chicago).

So does the Times’ opinion editor, Kingsbury (Columbia).

Moreover, the paper’s publisher (Brown), executive editor (Harvard), and managing editor (Cornell) all have Ivy+ degrees; 54% of the American degrees earned by members of the paper’s editorial board are from Ivy+ schools.

As for The Atlantic: its owner (Penn, Stanford), CEO (Stanford), and editor-in-chief (Penn) all went to Ivy+ schools.

In short, there is an Ivy+ bubble, and for those inside of it, Ivy+ schools loom very, very, very large. I appreciate that some of these folks are willing to criticize aspects of these schools. But they don’t need to feel that bad about it. Honestly. In fact, I bet they’d care much less what we thought of Ivy+ schools if they realized how seldom we did.

A dismissal of the New York Times or Atlantic might seem appropriate and tempting given the obvious waning influence of such publications. Other such Ivy+ echo chambers might prove more worrisome; more on that in a bit.

Both the Brooks critique of the Ivy+ and the Smarick critique of Brooks could have been stronger still if they had included a discussion of the Harvard vs. Penn State outcome research. By tracking the long-term outcomes of students who were admitted into Harvard but chose to attend Penn State, researchers have found that the relative value-added proposition of attending Harvard approximates that of attending Penn State. In other words, the best thing about Harvard seems to be the ability to get in rather than actual attendance.

The Brooks critique of a meritocracy gone wrong rings broadly true. Human beings are more than an ACT score. ACT scores can and have been manipulated in various ways, and some high demand universities seem to expect middle schoolers to found a multimillion-dollar organization to merit consideration. There are sections of our country where people would view it as a grave family dishonor to send their children to the University of State X. Thus, the selection bias might be seen as one toward a particular attribute (intelligence albeit imperfectly measured) and perhaps even more so toward an endurance of admission rituals.

Where does all this land? One might describe this as overrated people desperate to get into overrated institutions. If so, the Smarick critique might ring even more true, but what if another one of the echo chambers of these folks lies within the federal government and academia?

Wile E. Coyote is the patron saint of the American technocratic class. On the rare occasions in which he speaks, Wile E. occasionally would explain to the Looney Tunes audience that he is a “supra-genius” in an upper crust accent. Wile E. would of course constantly make elaborate and complex schemes to capture the Road Runner, only to have them backfire again and again and again. Fortunately, the only victim of Wile E. Coyote’s repeated folly was Wile E. Coyote himself.

This is alas not the case for many of the misbegotten schemes of Ivy Leaguers. Take for example Columbia Teacher College’s Lucy Calkins’ hugely destructive misadventure into reading instruction. Or Harvard’s Franklin Raines who helped bring us the subprime mortgage crisis. Or Cornell’s Anthony Fauci, who by my reading of accounts seems to have evaded prohibitions on gain-of-function research, including that conducted in Wuhan. These things didn’t just blow up in the faces of the “supra-geniuses.” They backfired on all of us.

Personally, I suspect that the selection process Brooks describes as denuded a dangerous number of American grandees of an attribute even more important than intelligence: humility. The lack of humility led previous generations to embrace horrible practices such as eugenics. The creation of the public school system in America also included absurdly overconfident assurances that prisons would be emptied, and innumerable benefits would rush forth.

As Douglas Carswell wrote in The End of Politics, “The elite gets things wrong because they endlessly seek to govern by design in a world that is best organized spontaneously from below. They constantly underrate the merits of spontaneous, organic arrangement, and fail to recognize that the best plan is often not to have one.” Whether Ivy+ universities are destructive or overrated, I propose that they can and have been some of both.

The Wall Street Journal ran an article which had your humble author giggling for hours afterwards called Sorry Harvard Everyone Wants to Go to College in the South Now. Nothing against Harvard, mind you. Some love hanging around with silver spoon kids trying to work out their misplaced guilt over their parents’ success with protests over micro-aggressions. If that is your cup of tea, then sip away. As the Wall Street Journal noted however a growing number of northern students have decided to try a different flavor of tea (sweet) down south:

A growing number of high-school seniors in the North are making an unexpected choice for college: They are heading to Clemson, Georgia Tech, South Carolina, Alabama and other universities in the South.

Students say they are searching for the fun and school spirit emanating from the South on their social-media feeds. Their parents cite lower tuition and less debt, and warmer weather. College counselors also say many teens are eager to trade the political polarization ripping apart campuses in New England and New York for the sense of community epitomized by the South’s football Saturdays. Promising job prospects after graduation can sweeten the pot.

The number of Northerners going to Southern public schools went up 84% over the past two decades, and jumped 30% from 2018 to 2022, a Wall Street Journal analysis of the latest available Education Department data found.

What kind of fun? How about Vanderbilt students carrying a goal post down Nashville’s Honky Tonk Highway in triumph after defeating the top ranked Alabama Crimson Tide? Ever been to the Grove in Oxford on a game day? The Ole Miss folks claim while they may not win every game, they have never lost a party. Take my word for it, you won’t regret putting it on your bucket list:

College students are not the only ones heading south. The Census Bureau has a nifty tool to allow you to track where young adults are leaving and where they are going. As an earlier Wall Street Journal article detailed:

Daniel Brookings Institution demographer William Frey details this in a September report. Describing what he calls “a virtual evacuation from many northern areas,” Mr. Frey writes the “movement is largely driven by younger, college-educated Black Americans, from both northern and western places of origin…But an undeniable reality, emphasized by Gov. DeSantis, is that this movement is overwhelmingly driven by the prospect of greater economic opportunity.

It is not just economic opportunity that might attract young adults south-educational opportunity just might do so as well, and not just of the college sort. What would cause a “virtual evacuation” for northern areas? How about things like the entire Chicago school board resigning in protest as a teacher union affiliated mayor plunges the district into a debt spiral?

In times like these, Chicagoans should ask themselves WWEMD (What Would Eddie Murphy Do?) Here’s a hint: that disembodied demonic voice is not urging you to hang around in Chicago. Quite the opposite:

Ryan graduated from Beacon College as one of five valedictorians.

LEESBURG – Ryan Sleboda is a college graduate with a degree in anthrozoology, a 4.0 GPA, and the distinction of being one of five valedictorians for Beacon College’s Class of 2024.

He’s sailing off to a future where he expects to own a business – a doggy daycare – and live on his own.

“That’s my motivation,” he said.

These are significant milestones for Ryan, who is on the autism spectrum.

Socially shy for most of his life, Ryan, 23, has cleared hurdle after hurdle thanks in part to the Family Empowerment Scholarship for Students with Unique Abilities, managed by Step Up For Students. It enabled him to attend a private school that set him on his journey of success.

He graduated from Pace Brantley Preparatory School in 2020 as valedictorian and senior class president.

“One door opened to another door every time,” his mother, Susan said, “and it all started with that initial door, getting that scholarship.”

***

There was a time when the idea of Ryan attending college and living on campus was a concept his mother didn’t even dare to dream.

“We set our expectations low, honestly,” Susan said. “For a time, we thought Ryan would always live with us. But he’s come so far, and this college has been amazing for him.

Family support played a great role in Ryan's success.

“Now, we're seeing a student who's graduated, who is not just further ahead than we had hoped but has blown away our expectations. He wants to own his own business. He wants to be an entrepreneur. What's better than that? He has truly exceeded our expectations.”

Beacon College is a four-year college in Leesburg. It was founded in 1989 for students with learning differences such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism, and dyslexia.

Its small student body (455 undergraduates) allows for a teacher-student ratio of no more than 1 to 15 and creates a more nurturing learning environment. Its dorm rooms allow students to build the self-confidence that comes with living away from home while attending college.

“There are a number of things we want for our students, and one of them is to be independent, so when they leave, they can be self-sufficient,” said Beacon College Provost Dr. Shelly Chandler. “Of course, we want them to be educated. We want them to be lifelong learners. But the main thing is we want them to find meaningful work and live a fulfilling life.”

***

Two members of Beacon College campus security paused their conversation to greet Ryan as he walked past them on a sunny midweek morning. A trio of coeds did the same as they passed by.

From across the street, a classmate shouted, “Hey, Ryan!”

![]()

“If he were an athlete, he’d be an MVP,” said Bryan Cushing, a Beacon College professor who has taught Ryan since his freshman year.

Ryan returned each greeting with a cheery “Hello.”

“Attending Beacon College has made me an extrovert,” Ryan said.

“That's very true,” Susan said. “He used to be quiet. And I don't want to say afraid, but shy and timid. It was hard for him to make friends. He was afraid of making mistakes. Beacon College has truly turned him into a leader.”

Ryan excelled at Pace Brantley, but that was a familiar, comfortable setting. College would be different. There would be new teachers and classmates. Ryan would have a roommate.

Like his older brothers, Matthew (Florida Atlantic University) and Jason (Florida State University), Ryan wanted to go away to college. He wanted that independence. He researched the universities in Florida but couldn’t find one that would fit his needs.

“They just don't have those best services provided for those with special needs,” Ryan said. “With me, I can't handle being in a big crowd as much because that's where my anxiety rises so much that I can't focus. And that's where my autism starts to overstimulate really crazy, even when it's in a school setting.”

Ryan learned of Beacon College when school president Dr. George J. Hagerty visited Pace Brantley during Ryan’s junior year. The school, located an hour from Sleboda’s home in Sanford, offers anthrozoology as one of its majors, and that appealed to Ryan’s love of animals.

The school also offered a three-week program called Summer for Success, where high school freshmen, sophomores and juniors live on campus and receive the full college experience.

Susan and her husband, Bill, didn’t know what to expect when they dropped Ryan off in Leesburg that summer. They were surprised at what they found when they returned three weeks later.

“Honestly,” Susan said, “I couldn’t believe he was the same person. He entered that Summer of Success program as a young boy, and when we picked him up, he was a young man.”

Ryan walked and talked with a self-confidence they had never seen in him. He was ready to go away to college.

“That's what a lot of families experience,” Chandler said. “And when they come in the first semester, boy, do we see growth. By the time they graduate, they're different people. They really are.”

***

Ryan’s four years at Beacon College weren’t all seashells and balloons. He learned roommates can be challenging. Keeping track of his class schedule and coursework took some getting used to. As did living away from home.

“I have to admit,” he said, “I was homesick at first.”

But he slowly escaped the cocoon he’d built around himself and began meeting daily challenges.

“He took a lot of risks on his own socially and academically to build that confidence,” Cushing said.

Ryan became a leader in the college’s orientation program and gravitated toward new students, eager to show them around and answer their questions.

As a junior, he traveled to Costa Rica to study the local ecology. He interned at a doggy daycare near his home before his senior year. That’s where he developed the idea of owning his own business.

Through all of it, the straight-A student in high school continued to earn top grades.

Cushing said watching Ryan develop during these past four years is why he teaches at Beacon College.

“So many other people would see our students and just dismiss them off the bat, and that's not fair because they all have an equal right to education, and they deserve to get this education and the experiences that come with going to college, the social stuff, the personal growth,” he said. “And if we can provide that, and they take advantage of it, it's really a beautiful thing.”

For the past dozen years, the GEO Foundation nonprofit has offered students enrolled at its high schools access to higher education through its college campus immersion program. A state grant for $8.3 million has allowed it to expand the program statewide.

A new study shows that the lines between K-12 and higher education are getting blurrier.

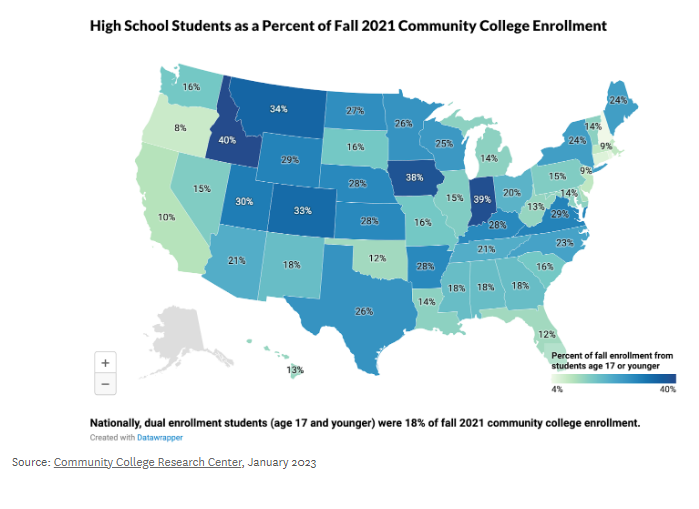

State of play: The Community College Research Center found enrollment declined after the pandemic among all age groups except one: Those younger than 18. A growing share of high school students are participating in dual enrollment programs that allow them to earn college credit. Today, one in five community college students are high school students.

Why it matters: The cost of a college degree continues to rise. So do feelings of boredom among high school students. Getting an early start on a degree can make college less costly and offer high school students more relevant learning opportunities. Some students end up earning associate degrees when they receive their high school diplomas.

Yes, but: Despite the increase in popularity of dual enrollment across the nation, participation remains uneven among states. Idaho, which reported 40% of its high schoolers enrolled in dual enrollment, took the No. 1 spot, followed by Indiana, with 39%. Oregon had the lowest participation, with 8%. Florida reported 12%, which was below the national average of 18% during the fall of 2021.

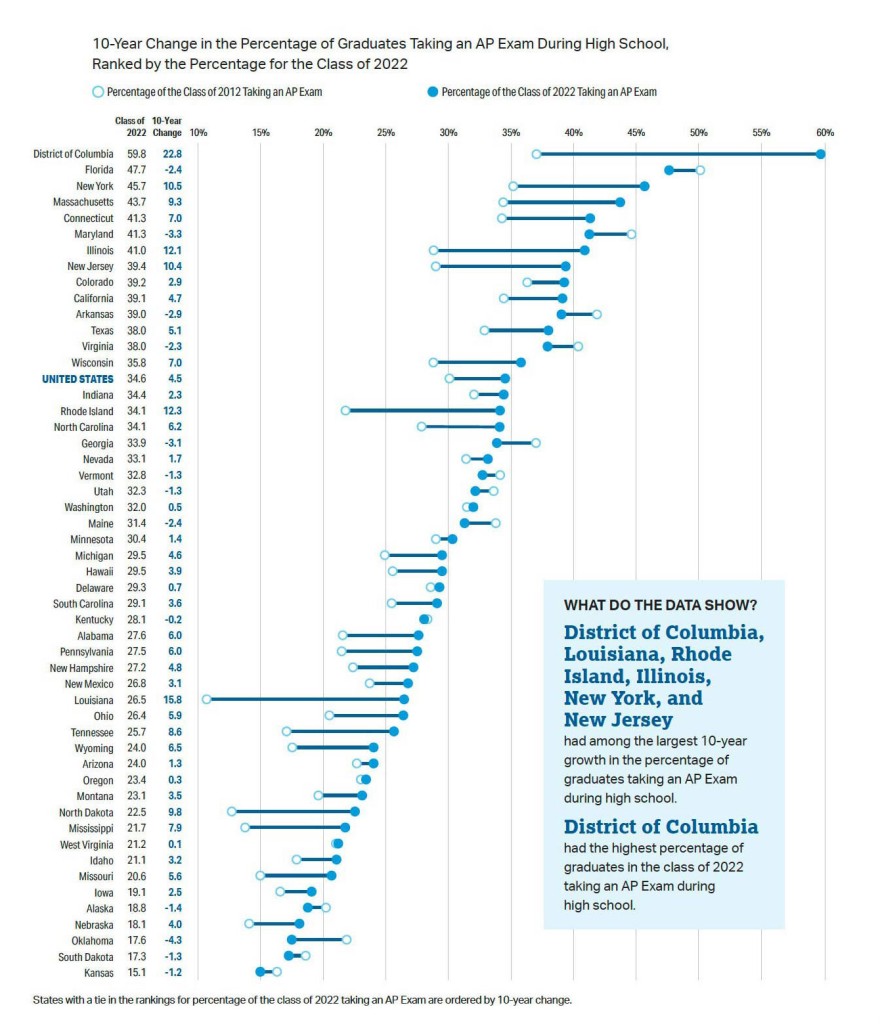

Another way to play: Some states with lower dual enrollment participation rates reported higher participation in Advanced Placement courses, according to the College Board, which administers the AP program. Florida ranked second among the states, with nearly half of the class of 2022 taking an AP exam, another common path to earning college credit during high school.

Everyone wins: Regardless of what that looks like — AP, International Baccalaureate, Cambridge, dual enrollment, or career apprenticeship programs — students are finding new ways to gain affordable access to postsecondary education. Some schools, like the Indiana-based charter network GEO Academies or Florida's collegiate high schools, have designed their models around giving students access to higher education institutions or postsecondary career training.