Hope, Caleb and Mary Hayes attend school on Florida's Family Empowerment Scholarship for Students with Unique Abilities.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Jonathan Butcher, Will Skillman Fellow in Education at the Heritage Foundation and a reimaginED guest blogger, and Jason Bedrick, a research fellow at the Heritage Foundation’s Center for Education Policy, appeared Saturday on orlandosentinel.com. You can listen to reimaginED senior writer Lisa Buie’s podcast with Emily Hayes here.

As a mother of five children, Emily Hayes knows that every child has different needs. And she is keenly aware that these needs change over time.

This means life at home must change as children grow and, so does life at school — or wherever a child is learning.

This is a lot for any parent to handle. Especially parents of children with special needs.

As a mom living in Port St. Lucie, though, Emily had access to K-12 education savings accounts — formerly known as Gardner Scholarships and now called Family Empowerment Scholarships for Students with Unique Abilities (FES-UA).

These flexible scholarship accounts allowed Emily to choose different education products and resources at the same time for her children, from textbooks to personal tutors and beyond.

The accounts “have the flexibility to change with the kid,” Emily says, which has allowed her and her husband to specifically meet each of their children’s needs with personal tutors and therapy services and in recent years, a private school. “Each of [my children] has so many different needs. And it changes year-to-year as they progress year to year,” she says.

Two of her children are on the autism spectrum; another has complications related to brain and spinal development.

Emily’s children are among the 25,000 Florida students using these accounts. Another 84,000 are using vouchers to attend K-12 private schools, and 80,000 more attend private schools using scholarships funded by charitable contributions to scholarship-granting organizations, such as Step Up for Students.

With the breadth and depth of Florida’s private education landscape, the state is ranked first in a new Heritage Foundation survey of all 50 states and Washington, D.C., in the areas of education choice, academic transparency, low regulations on schools, and a high return on investment for taxpayer spending on education. In three of the four categories examined Florida ranks among the top three nationwide.

For education choice, Florida ranks third behind Arizona and Indiana. All three states offer families numerous pathways to choose the learning environment that works best for their children. Studies find that education choice policies lead to higher levels of achievement and educational attainment as well as greater civic participation and tolerance, and lower levels of crime.

But for parents to choose well, they need information. That’s where the Sunshine State truly shines, earning first place for academic transparency. Earlier this year, Gov. Ron DeSantis signed a bill that allows parents to see a list of materials that teachers are using in classrooms and view the catalogue of school library books. State officials also approved a proposal saying teachers and students must be free to engage in debates in class, but no one can be compelled to believe ideas, such as the idea that — because of their skin color — individuals deserve blame for past actions committed by others.

The high degree of transparency enables parents to hold schools accountable directly. Instead of trying to ensure quality through top-down regulations and red tape, Florida relies on bottom-up accountability, which is why it ranks second in the nation for regulatory freedom.

Schools and teachers have a high degree of freedom to operate as they see fit, within the boundaries set by age-appropriateness and civil rights laws, and parents provide accountability through their freedom to choose the schools that work best for their kids.

Florida lawmakers’ embrace of choice, transparency and regulatory freedom has produced one of the highest returns on investment in the nation, ranking seventh nationwide. While keeping spending within reason, Florida has steadily improved its performance on the National Assessment for Education Progress over the past two decades, rising to 17th nationwide in its combined fourth-grade and eighth-grade math and reading scores.

As for Emily, she says that “the kids are thriving.” The school aligns with her family’s values and has provided “targeted therapy” for each child — a winning combination.

But it took more than a single assigned school to help her and her children find success.

“Not every school is going to meet the needs of every kid,” Emily says, which makes education choice essential.

If an assigned school anywhere in the country is not meeting a child’s needs, parents should point to Florida and ask their lawmakers, “Why can’t we have more options, too?”

This 4,468-square-foot South Tampa home, located in the A-rated Mabry Elementary School zone, is listed for sale at $1.8 million.

When my husband and I bought our first home as newlyweds, we didn’t think to ask what public schools served the area. We were young, childless, and hyper-focused on our journalism careers, so our concerns centered on ease of commuting to work and shopping.

Then there was the fact that we had chosen to work in an industry that pays its workers barely a living wage, so our search was limited to a handful of neighborhoods.

We ended up selling that home at a loss but learned a valuable lesson: Because ZIP codes for the most part dictate where kids go to school, performance and reputation of public schools affect home prices, and those prices determine for the most part who gets access to those schools.

We were still childless but wiser as we house hunted after relocating to Florida. We asked questions about the reputations of the schools where students were zoned in our prospective neighborhood. We conducted online research and gleaned information from co-workers. In the end, an important point that factored into our decision: the development we liked was located near a site earmarked for a new elementary school.

I reflected recently on the difference between what I knew 20 years ago and what I know now when a Step Up For Students colleague shared a quarterly report delivered from a South Tampa real estate firm to homeowners in high-income ZIP codes. The report broke down home prices by school zone. No hidden agenda here, as the information is available to anyone with access to the Multiple Listing Service; providing this information is a common practice of real estate firms to help potential sellers time the market.

The report was eye opening, nevertheless. The eight schools it included were in areas with median home prices ranging from $805,455 to $2.37 million. Based on data collected by the Florida Department of Education, these schools had – surprise! – “A” grades from the state for the past three years.

All the schools have white student populations of 60% or higher. The school with the highest percentage of students classified as “economically disadvantaged,” Wilson Middle School, reported 28%, while the lowest, Mabry Elementary School, reported 8.7% as meeting those criteria.

This 1,486-square-foot home, located in the F-rated Kimbrell Elementary School zone, is listed for sale at $230,000.

Compare that with F-rated Kimbrell Elementary School, which is one Hillsborough County’s 39 low-performing schools. Department of Education data show just 10.3% of Kimbrell’s students are white and nearly 95% are classified as economically disadvantaged. More than 6% are homeless. What’s more, the school attracts only 48% of its neighborhood children. The rest attend district-run charter schools, a magnet school, or some other form of education choice.

Jason Bedrick, director of policy for EdChoice, a national nonprofit organization devoted to advocating for education choice, is on the record as saying, “There’s no such thing as a ‘public’ school.” Bedrick wrote about this in an essay for the Cato Institute in which he debunked an oft-cited claim education choice critics use while trying to thwart establishment or expansion of choice programs: Private schools get to pick and choose their students, but public schools must take everyone.

Public schools, he wrote, “are more appropriately termed ‘district schools’ because they serve residents of a particular district, not the public at large. Privately owned shopping malls are more ‘public’ than district schools.”

Bedrick argued this wouldn’t be a problem if every school was of the same high quality, but sadly, that is not the case.

Not all families live in a state with access to education choice. Bedrick and Lindsey Burke, deputy director of the Johns Hopkins Institute for Education Policy, told the story of a Washington, D.C., couple, both law enforcement officers, who lied about where they lived so their three children could attend higher quality district schools.

Though the D.C. Opportunity Scholarship Program, established in 2003, has offered relief to the area’s poorest families, Bedrick and Burke wrote that education savings accounts – accounts parents can use to purchase a wide variety of educational products and services using a portion of the public funding that would have been spent on their child at his or her assigned district school – is a model that allows parents to completely customize their child’s education plan to ensure the best fit.

Eight states, including Florida, have established ESAs, though some, including Florida’s, are available only for students with certain special needs.

Universal ESAs would allow students currently zoned for F-rated Kimbrell Elementary the opportunity to attend a school with a state-designated letter grade closer to those of the south Tampa schools featured in the real estate report, as well as access to tutoring or enrichment programs now available only to families who can afford to pay for them.

Our house is now worth nearly triple what we paid in 1997. The fact that the nearby district schools are consistently A-rated no doubt has contributed to the steady climb in home values. Yet surrounded by A-rated schools, we sent our son to a private kindergarten on a state scholarship, and later to other high-performing district schools outside our zone, because those environments were the best fit for him – and because we could afford transportation.

If only everyone had those options, regardless of their ZIP code.

“That which purifies us is trial, and

“That which purifies us is trial, and

trial is by what is contrary.”

John Milton, Areopagitica

My thanks to those eminent school choice advocates Larry Sand of California and collaborators Robert Enlow and Jason Bedrick of EdChoice in Indiana. I recommend reading their recent critiques here and here of the design of those half-dozen model statutes for choice that Stephen Sugarman and I pumped out from the 1960s until the 21st century.

These critics worry that our models are too complex, hence, self-defeating at the polls or in the legislature; and they fret even more that we are focused principally upon lower-income parents.

For them, the structure must be simple, as Milton Friedman imagined it, with equal subsidy for every child of every family in the same grade and with little or no regulation of private school admission policy or recruitment strategies.

Sugarman and I make them unhappy, because we would have participating schools set aside their unchosen applications for a final random selection of a fraction of its entries, giving the unchosen child of the poor a chance at subsidized admission. We would also require the school to make itself known in the open market, trying thereby to assure that lower-income parents have the chance to learn what their new responsibility requires in the way of sophistication about their options.

Our critics recognize the suffering of the lower-income family under the status quo, but they insist that this problem is best addressed by a Friedman-blessed system of subsidy that includes all parents, even those who least need it. It is this alone, they believe, that will bring the civic liberation of the poor.

They are best, also we hear, because this pure system which they favor is politically the most saleable; any focus upon the poor is unpopular.

I must have overlooked some such rousing success of the pure market approach in capturing the voting hearts of our 50 state electorates. For many years, the Friedman folks in many states have been running ballot initiatives for universal vouchers. Their level of success is unimpressive.

Still, this issue of the universality of any system of subsidized choice seems to me the lesser of two central questions.

So, let us try another plebiscite offering vouchers to the rich and poor alike. The core dispute will then be the nature and extent of state government regulation of participating schools.

Sugarman and I have long felt concern over such matters as admission policy advertising (targeted or universal), procedural rules for expulsion and so on. At least in the short run, parents who have never chosen will need to acquire some of the sophistications of the middle class.

I can understand how pure market minds could continue to draw the line at certain forms and degree of regulation; so would I. But, just maybe, they could help to make it “efficient” in the way least intrusive of the participating private school. What puzzles me is their reluctance even to consider how the untutored parental mind needs help to become a wise consumer and how the seller must rescue such mothers and fathers with simple information about just who and what this particular school is.

Most important, if a school participates, it should be ready at the end of the admission process to take a few children – say 15% – at random, children whom they had not already picked from among their applicant pool. In short, it has seemed fair and rational to ask the seller to undertake a wee bit of “social integration.”

Finally, and most important, we should ask these pure market folks ever to keep in mind that decisions about design will be made by 50 individual state governments. Might it not be to our civic good as a nation to watch and learn from the experience of those states with a variety of statutory models just what is popular and what works?

Editor’s note: Robert Enlow, president and CEO of EdChoice, and Jason Bedrick, director of policy at EdChoice, provided the following response to a post from redefinED columnist John Coons.

In a recent redefinED blog post, school choice icon John Coons proposed finding common ground between two groups of education reformers whom he calls the “Miltonites” or “marketeers” (supporters of a free-market approach to educational choice with universal eligibility in the mold of Milton Friedman) and the “voucher left” (those, like Coons, whose primary concern is improving the well-being of the poor). His point is that what unites the two groups is much more—and more important—than what divides them, so they should find ways to work together as “happy co-conspirators” to advance educational choice.

As two staunch Miltonites, we couldn’t agree more.

Advancing choice and opportunity requires a broad and ideologically diverse coalition, as when the Republican governor of Wisconsin, Tommy Thompson, worked with Democratic legislator Polly Williams to enact the first voucher program of the modern era. More recently we’ve also seen a largely successful coalition of staunch conservatives and ardent liberals working together to advance criminal justice reform.

As with any diverse coalition, however, there is bound to be some healthy disagreement, particularly over the means to achieve shared ends. In the choice coalition, the fault lines have often been over access (universal vs. targeted) and regulations (libertarian vs. equalitarian).

First, the common ground. As with many on the social justice wing of the school choice movement in recent years, Coons now appears ready to support Miltonite universal access—so long as the financial support for the disadvantaged is greater. On this front, today’s Miltonites are already pretty much in agreement in principle though there may be some disagreement over the details.

When it comes to regulations, however, the differences over means are more profound. While well-intended, the regulations Coons proposes are likely to stymie the ability of choice programs to benefit the very people Coons wants to help the most. Instead, we propose that Miltonite means are best to achieve Coonian ends.

Universal Choice

Whereas in the past, Coons and Friedman ran dueling proposals that differed sharply over eligibility, now Coons proposes a universal approach in which “at least a trophy amount to the well-off in recognition of their civic role as parent, while awarding the poor the full economic reality of that same parental responsibility and authority.” It’s not clear what a “trophy amount” means in practice, but while we think it is important that everyone receive a substantial scholarship, we support giving additional aid to disadvantaged populations, such as students with special needs, English Language Learners, and children from low-income families.

Universality is essential for both policy, political, and personal reasons. In terms of policy, targeted choice programs may fill empty seats in existing schools, but only the widespread availability of educational choice will lead to the systemic transformative change that our K-12 system needs.

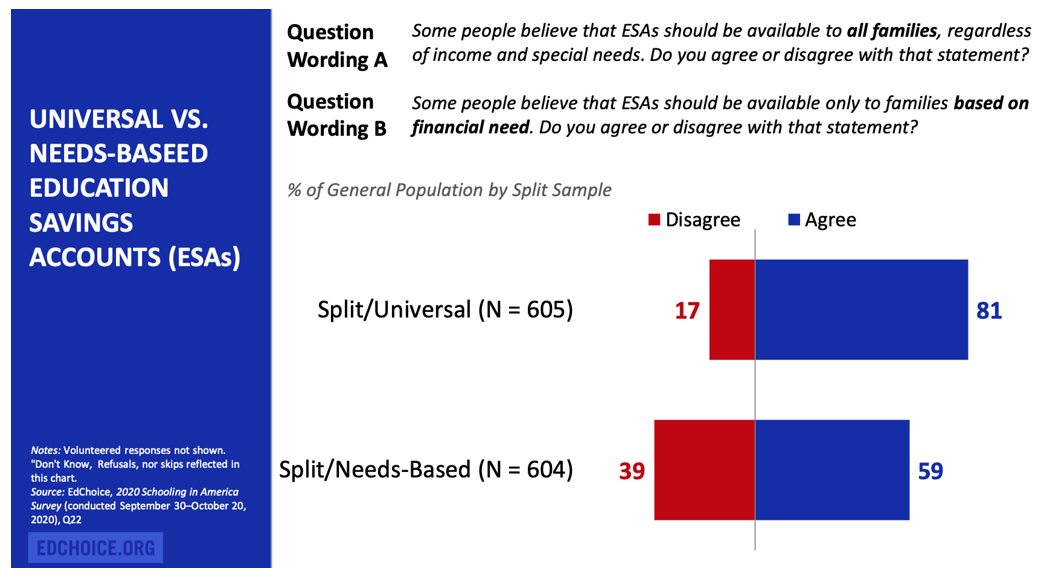

Universality is also more politically sustainable. There is significantly higher public support for universal programs than targeted ones. EdChoice’s latest Schooling in America Survey found that 81 percent of Americans support universal choice policies while only 17 percent oppose them. By contrast, only 59 percent supported making choice programs available based on financial need while 39 percent opposed doing so.

Moreover, as Milton Friedman often observed, “Programs for the poor are poor programs.” Welfare is often on the chopping block, but Social Security never is. Likewise, programs that serve upper-middle-income families who have political capital tend to be better-run than those that serve only the poor. One need look no further than the district schools serving well-off families compared to those that serve lower-income families. The poor are best served by being in the same boat as the more advantaged.

On the personal level, low-income families don’t want to feel like or be seen as charity cases. Families who send their children to a public school are receiving a government subsidy, but they don’t feel like a charity case because everyone gets access. No wonder then that our recent poll found significantly higher support for universal choice among low-income families. Among respondents earning less than $40,000 annually, 92 percent supported universal access while only 66 percent supported means-testing.

As we noted above, we support giving additional aid to disadvantaged families, but we should be clear-eyed about the tradeoffs and wary of pitfalls. Families who must prove their income face additional barriers, including intrusive questions and a significant amount of paperwork. Also, we must be careful that we don’t create a poverty trap that takes away benefits as a household’s income rises. Educational choice programs should assist low-income families by expanding opportunity but should not ever be designed in such a way as to create a disincentive for families to improve their financial situation.

Ultimately, universal access to educational choice is about erasing the invisible but all-too-real lines that divide our nation’s education system into haves and have-nots. A Friedman noted in Free to Choose:

The tragedy, and irony, is that a system dedicated to enabling all children to acquire a common language and the values of U.S. citizenship, to giving all children equal educational opportunity, should in practice exacerbate the stratification of society and provide highly unequal educational opportunity.

Ending this stratification—ending the lines between us all and creating opportunity for all especially the most vulnerable—is the true goal of the Miltonite view of educational opportunity.

The Role of the Market

A well-functioning market is necessary to provide families with a diverse array of educational options and to spur systemic innovation and improvement. Coons is open to the importance of the market to educational choice but takes Friedman to task for taking a “let the market rip” approach, claiming:

It was to [Friedman] an economic sin to favor lower-income families in either the amount of the subsidy or the design of regulation for participating schools. The focus for him was not on the role of the parent, but rather the achievement of simplicity and laissez-faire in the economy.

This does not do justice to Friedman’s views, which were considerably more nuanced.

What Coons calls Friedman’s “let it rip” approach is really Friedman’s sincere belief in parents and their ability to choose. As Friedman wrote in Free to Choose:

Parents generally have both greater interest in their children’s schooling and more intimate knowledge of their capacities and needs than anyone else. Social reformers, and educational reformers in particular, often self-righteously take for granted that parents, especially those who are poor and have little education themselves, have little interest in their children’s education and no competence to choose for them. That is a gratuitous insult. Such parents have frequently had limited opportunity to choose. However, U.S. history has amply demonstrated that, given the opportunity, they have often been willing to sacrifice a great deal, and have done so wisely, for their children’s welfare.

Moreover, Friedman’s opposition to certain regulations stemmed not from a sense that they were a “sin” against a free-market religion but rather from his empirical studies of how markets work and how certain well-intended regulations can have unintended consequences.

As Friedman himself wrote in the Wall Street Journal in 2000:

I have nothing but good things to say about voucher programs, like those in Milwaukee and Cleveland, that are limited to a small number of low-income participants. They greatly benefit the limited number of students who receive vouchers, enable fuller use to be made of existing excellent private schools, and provide a useful stimulus to government schools. They also demonstrate the inefficiency of government schools by providing a superior education at less than half the per-pupil cost.

But such programs are on too small a scale, and impose too many limits, to encourage the entry of innovative schools or modes of teaching. The major objective of educational vouchers is much more ambitious. It is to drag education out of the 19th century – where it has been mired for far too long – and into the 21st century, by introducing competition on a broad scale. Free market competition can do for education what it has done already for other areas, such as agriculture, transportation, power, communication and, most recently, computers and the Internet. Only a truly competitive educational industry can empower the ultimate consumers of educational services – parents and their children.

Coons claims that the Miltonites have “succeeded largely in giving subsidized parental choice the image of Friedman himself,” meaning universal programs that have “nearly zero regulation of the chosen providers.” In reality, the Miltonites have been all too willing to settle for small, targeted programs that often come with regulations that undermine their effectiveness.

As we highlighted in a recent essay for the American Enterprise Institute, markets are essential for creating a feedback loop that organically expands options and improves quality over time. In the words of AEI’s Yuval Levin, markets enable the channeling of “social knowledge from the bottom up” rather than “impos[ing] technical knowledge from the top down” via a Hayekian three-step process of “experimentation, evaluation, and evolution.”

Markets are ideally suited to following these steps. They offer entrepreneurs and businesses a huge incentive to try new ways of doing things (experimentation); the people directly affected decide which ways they like best (evaluation); and those consumer responses inform which ways are kept and which are left behind (evolution).

This three-step process is at work well beyond the bounds of explicitly economic activity. It is how our culture learns and evolves, how norms and habits form, and how society as a general matter “decides” what to keep and what to change. It is an exceedingly effective way to balance stability with improvement, continuity with alteration, tradition with dynamism. It involves conservation of the core with experimentation at the margins to attain the best of both.

Policymakers should be careful to avoid policies that unduly interfere with this process. As Jason Bedrick and Lindsey Burke explained in greater length in chapter nine of School Choice Myths, some of Coons’ proposed regulations have unintended consequences that undermine the ability of choice programs to aid the very people they’re intended to help. For example, as Bedrick and Burke explain, such open-admissions requirements can restrict the diversity of options available to scholarship students:

Open-admissions mandates prevent families from using vouchers at schools with certain missions or those that are oriented around voluntary communities, such as religiously affiliated schools or single sex schools. They also discourage participation among schools that are designed to serve certain types of students, whether the academically gifted, students with particular special needs, or those with a penchant for STEM or drama and the arts.

College voucher programs, like Pell Grants, are publicly funded without imposing open-admissions requirements out of a recognition that the purpose of the public funding is to expand educational opportunities for students to enroll in the learning environments that are the right fit for them. That requires a diversity of options, including schools that are geared toward particular student populations or that have particular missions or religious affiliations.

Such regulations can also affect the quality of available options. Louisiana’s voucher program is the most regulated in the country, imposing open admissions, the state test, and price controls to guarantee low-income families access to high-quality schools. What happened is that most private schools refused to participate, and Louisiana’s voucher program became the first in the nation to produce negative effects in a random-assignment study.

How did that happen?

Well-intentioned regulations are the likely culprit. In a survey by the American Enterprise Institute, three out of four Louisiana private school leaders who opted not to have their school accept voucher students cited concerns about the effects of the open-admissions requirement. As Bedrick and Burke explained, there were important differences between the participating and non-participating schools:

These concerns [about regulations] appear to have dissuaded many of the higher-performing schools from accepting [Louisiana Scholarship Program (LSP)] students, so participating schools were of lower quality, on average. One of the initial LSP studies contained some suggestive evidence of this. In the decade before the LSP was expanded statewide, the non-participating schools experienced modest enrollment growth (about 3 percent, on average). By contrast, over the same period, the participating schools experienced a significant decline in enrollment (about 13 percent, on average). In other words, private schools that had been able to attract students before the LSP expansion tended to reject the vouchers, while voucher-accepting schools tended to be those where enrollment had been falling.

These concerns are not confined to Louisiana. Another multi-state study found that admissions mandates significantly reduced the likelihood that private schools would participate in a potential school choice program. The number of private school principals who were “certain to participate” in a school choice program dropped by around 17 to 21 percentage points, or 70 to 84 percent, if the program had an admissions mandate.

By contrast, Florida eschews admissions mandates and other Louisiana-style regulations yet more than 130,000 low-income students are now attending the schools of their families’ choice. Moreover, far from “creaming,” studies show that Florida private schools are admitting scholarship students who were lower-performing, on average, than their demographic peers before receiving a scholarship. In other words, as Louisiana and Florida show, open-admissions mandates are neither necessary nor sufficient to expand access for lower-income families—and may even have the opposite effect.

Better Together

Miltonites and Coonians are united in a shared desire to improve the lot of “the least among us.” We should also share a commitment to learning from what has and hasn’t worked. The past three decades of experience with educational choice show that Miltonite means are the surest path to achieving Coonian ends.

Civility and respect are core values we promote at redefinED, so we were pleased to read the well-mannered exchange between Jason Bedrick and Kevin Welner about the pros and cons of tax credit scholarships. Readers who missed their back and forth can get caught up beginning here, and continuing here, here, here, here and here.

Unfortunately, their exchange was motivated by a column by Washington Post blogger Valerie Strauss, which was a collection of false assertions and hyperbolic rhetoric. After Bedrick rebutted Strauss’ attacks, she had the good sense to step back and let Professor Welner take over.

Welner has chosen to build his career around opposing tax credit scholarships, and, while some of his previous writings have also suffered from over generalizations and unsubstantiated assertions, his rhetoric has become more measured in recent months, as my colleague Jon East noted last December.

I can’t add much to Bedrick's outstanding rebuttals, but I do wish the parents’ voices could be included in these exchanges. I spend hours every week talking with parents, grandparents, and foster parents about the extraordinary challenges they face raising low-income children. For them the tax credit scholarships are not about ideology or politics; they’re about another tool they can use to keep their children alive, out of jail and on the path to becoming a successful adult.

I suspect Welner would be a lot slower to condemn these scholarships if he spent more time talking to the parents and children who are using them.

Charter schools. Brooksville's first charter school, one with a STEM focus, will open this fall, reports the Tampa Bay Times. Competition from charter schools is forcing the Palm Beach County school district to think harder about its needs and priorities, reports the Palm Beach Post. Charters are also sparking debate among Palm Beach school board members about how much help they should give struggling charters, the Post also reports. An op-ed in the Miami Herald raises concerns about charter schools' diversity and financial incentives. The Sarasota Herald-Tribune profiles the principal of the Imagine charter school that is trying to break free from the parent company.

Magnet schools. The Tampa Tribune applauds the Hillsborough school district for creating a magnet tied to the maritime industry.

Alternative schools. Troubled girls get a fresh start at a sheriffs' youth ranch in Polk County. Orlando Sentinel.

Tax credit scholarships. Great back-and-forth between scholars Kevin Welner at NEPC and Jason Bedrick at Cato, with Florida's program a big part of their debate. Cato at Liberty.

Tax credit scholarships. Great back-and-forth between scholars Kevin Welner at NEPC and Jason Bedrick at Cato, with Florida's program a big part of their debate. Cato at Liberty.

School choice. It's often partisan. Sunshine State News.

Parent trigger. Education Commissioner Tony Bennett raises a constitutional question. The Florida Current. (more…)