This is the latest post in our series on the center-left roots of school choice.

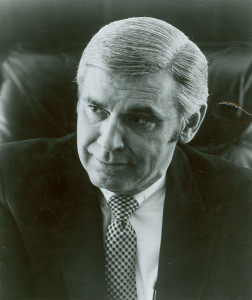

U.S. Congressman Leo Ryan was a popular Democrat who favored school choice. In 1978, he started working with Berkeley law professors Jack Coons and Stephen Sugarman on a plan to put school choice on the statewide ballot in California. An early poll showed 59 percent of voters were in support.

All of us know Lincoln was assassinated. But not many know the twist of fate that left historians asking: What if? Had it not been for a clown of a cop named John Frederick Parker – who was supposed to be protecting the president at Ford’s Theatre, but instead slipped next door to the Star Saloon – America after the Civil War may have coursed in dramatically different directions.

The history of school choice has its own forgotten twist of fate.

It involves Berkeley law professors, a murderous cult, and U.S. Rep. Leo Ryan, a school choice Democrat. Given relentless attempts by choice critics and the press, in this age of Trump and hyper-tribalism, to portray choice as right-wing madness, it’s worth revisiting Ryan and what happened 40 years ago. Would white progressives still view choice as a Red Tribe plot had white progressives been the first to plant the flag? And in big, blue California to boot?

In 1978, Berkeley law professors Jack Coons and Steve Sugarman laid out a social justice case for school choice in “Education by Choice,” a book that also offered a detailed policy blueprint. The prevailing system of assigning students to schools by zip code, they argued, was elitist and dehumanizing to low-income families. Their sweeping alternative included private school vouchers and independent public schools (which we now call charter schools). It also included visions of a system that would allow parents to build their kid’s educational programs a la carte, like today’s education savings accounts.

In 1978, Berkeley law professors Jack Coons and Steve Sugarman laid out a social justice case for school choice in “Education by Choice,” a book that also offered a detailed policy blueprint. The prevailing system of assigning students to schools by zip code, they argued, was elitist and dehumanizing to low-income families. Their sweeping alternative included private school vouchers and independent public schools (which we now call charter schools). It also included visions of a system that would allow parents to build their kid’s educational programs a la carte, like today’s education savings accounts.

Coons and Sugarman wanted to plant seeds, not spark an instant revolution.

But then, serendipity.

Congressman Ryan, enjoying his third term representing the San Francisco Bay area, was a former public-school teacher and a product of Catholic schools. “Education by Choice” moved him. As fate would have it, his cousin went to church with Coons. So he had her invite Coons to dinner.

Ultimately, the professor and the congressman decided they’d try to get the California Initiative for Family Choice on the statewide ballot. All they needed was enough signatures. Ryan agreed to be the face of the campaign.

Choice couldn’t have found a better spokesman. Before Ryan was elected to Congress, he was a state lawmaker who practiced what one newspaper called “investigative politics,” and his aide Jackie Speier – now U.S. Rep. Jackie Speier – called "experiential legislating."

Ryan worked as a substitute teacher to immerse himself in high-poverty schools. He went undercover to experience Death Row at Folsom Prison. As a Congressman, Ryan trekked to Newfoundland to investigate the slaughter of baby seals, and even laid down on the ice to save a seal pup from a hunter.

It’s not a stretch to think Ryan’s popularity would have rubbed off on the ballot initiative.

This is the all-in-one version of our recent serial about efforts to put school vouchers on the 1980 California ballot. It's part of our ongoing series on the center-left roots of choice.

The woman stopped the professor as they were leaving church near campus.

It was the fall of 1978 in northern California, and Jack Coons was a local celebrity. Or at least as much a celebrity as you can be if you’re a legal scholar who specializes in education finance.

He and Stephen Sugarman, a fellow law professor at the University of California, Berkeley, had been central figures in a series of court decisions in the 1970s that would dictate a more equitable approach to how California funds its public schools.

They had also just written a provocative book.

It called for scrapping the existing system of public education, and replacing it with one that gave parents the power to choose schools – even private schools. This stuff about “vouchers” was out there, but intriguing enough to generate some buzz. Newsweek gave it a plug.

My cousin is Congressman Leo Ryan, the woman told Coons. He’s interested in education.

Why don’t you and your wife join us for dinner?

***

It sounds crazy, but that chance encounter could have changed the face of public education in America. For one wild year in late ‘70s California, liberal activists set the stage for the most dramatic expansion of school choice in U.S. history.

Today’s education partisans have no clue it almost happened. But it almost did. And if not for some remarkable twists of fate, it might have.

In the 1960s and ‘70s, school choice was capturing the imagination of progressives who thought poor kids were being savaged by elitist public schools. Liberal intellectuals in places like Harvard and Berkeley were happy to tinker with the notion of school vouchers encapsulated by conservative economist Milton Friedman in 1955. They tried to cultivate varieties that included controls they believed necessary to ensure fairness for low-income families.

John E. “Jack” Coons and Stephen D. Sugarman were among them. And in 1978, they unexpectedly got an opening to put their vision of school choice on the ballot in the biggest state in America.

It started with the dinner invitation.

***

Cue “Staying Alive.”

Disco was king. Jimmy Carter was president. And across the bay from Berkeley, the punk band Dead Kennedys was blasting its first angry chords. But in 1978, Coons and Sugarman still hadn’t gotten the carbon-copy memo that the ‘60s were over.

The ballot initiative they detailed in their 1978 book, “Education by Choice,” wasn’t gradual change, organic growth, nibbling at the edges.

It was revolution. (more…)

This is the latest in our series on the center-left roots of school choice, and the last part of a serial about a proposed voucher initiative in late ‘70s California. In Part III, libertarian choice supporters reject a ballot proposal pitched by Berkeley law professors, and offer their own.

The professors wanted Milton Friedman’s blessing. So did the libertarians.

Calling Friedman was the “first and natural thing to do,” Berkeley law Professor Jack Coons recalled in an interview. The two had known each other since the early 1960s, when both lived in Chicago. Coons hosted a radio show; Friedman was a frequent guest.

As luck would have it, Friedman was now based at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University, in nearby Palo Alto. He and Coons and their wives occasionally met for dinner.

Initially, Friedman was excited and encouraging about the ballot initiative, Coons said. Then he wasn’t.

The regulations spooked him, Coons said. Friedman never told him directly. But he heard as much from potential donors to the initiative campaign, and it wouldn’t have been surprising. Friedman’s biggest fear about school choice was government intrusion.

According to Coons, donors told him Friedman had been in contact with them and said the plan was wrong-headed. He convinced them to hold off on contributions, and to wait for better school choice proposals down the road.

***

The libertarians had better luck.

Activist Jack Hickey said he sent Friedman a copy of his "performance voucher" proposal, and talked to him by phone. He said Friedman liked it enough to give it a positive review in writing. As proof, he produced a letter from Friedman on Hoover Institution letter head.

Friedman wrote that he liked how the performance voucher would curb government’s role in education, but was bothered by heavy reliance on standardized testing. He concluded, though, that “any one of the three approaches (an unrestricted voucher, your approach, or an appropriately designed tax credit) would be vastly superior to our present system.”

Both David Friedman, Milton Friedman’s son, and Robert Enlow, president of the Friedman Foundation for Educational Choice, said the letter appears to be authentic.

***

For some, two competing choice proposals weren’t enough. In the summer of 1979, petitions began circulating for a third. (more…)

This is the latest in our series on the center-left roots of school choice, and Part II of a serial about a voucher ballot initiative in late ‘70s California. In Part I, law professors Jack Coons and Stephen Sugarman find a surprise supporter in U.S. Rep. Leo Ryan.

The Berkeley professors had found a powerful ally.

Congressman Leo Ryan was popular and fearless, a liberal with a maverick streak, a square peg with a common touch. It’s a safe bet he was the only member of Congress with a master’s in Elizabethan literature. And importantly for a ballot initiative that sought to make school choice the law of the land, he had been a teacher in California public schools.

Ryan also had a knack for making headlines.

Before election to Congress in 1972, he served nine years in the state assembly, where he became famous for exploring the nitty gritty behind the news. One newspaper called it “investigative politics.”

After riots in Los Angeles, Ryan worked as a substitute teacher in the Watts neighborhood. A few years later, he went undercover to experience death row at Folsom Prison. As a congressman, he visited Newfoundland to investigate the slaughter of baby seals, at one point laying down on the ice between a hunter and a seal pup.

As fate would have it, Ryan was also a voucher guy.

Years later, Jackie Speier, his former aide, would point to his support for school choice as a prime example of his political independence. Ryan “seemed unlike other politicians,” Speier said. “He was provocative; he didn’t mince words or beat round the bush; he told you what was on his mind whether you wanted to hear it or not; and he took pride in not being able to be pigeonholed into any one ideology.”

Ryan may have been willing to buck his party on vouchers. But it’s also true it wasn’t as odd for Democrats in the 1970s to back public support for private schools.

In 1977, Democratic U.S. Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan introduced a bill for tuition tax credits that drew 50 co-sponsors – 26 of them Republicans and 24 of them Democrats. At that time, the previous three Democratic candidates for president, Hubert Humphrey, Eugene McGovern and Jimmy Carter, had backed similar proposals on the campaign trail.

According to Coons, Ryan was all in on the voucher initiative.

After their last meeting, he said Ryan told him: “You guys are going to polish this up as best you can, and we’ll get ready to announce it and start pushing it through the process just as soon as I get back.”

The congressman was headed to South America.

***

As word spread, panic mushroomed.

The Los Angeles Times predicted the voucher initiative would be “the biggest and most bitter fight over schools in many years.” State Superintendent Wilson Riles predicted “chaos.” The executive secretary of the powerful California Teachers Association, Ralph Flynn, said his group would defeat the proposal “whatever the cost.”

Even Al Shanker, the legendary leader of the American Federation of Teachers, weighed in, saying the California proposal could produce “the fight of the century.”

By early 1979, Riles was urgently contacting supporters, mobilizing for a statewide campaign.

If this thing gets on the ballot, he told the San Jose Mercury News, “who knows what might happen.”

Game on.

***

Coons and Sugarman didn’t dream up their plan on a whim. They had been refining it for a decade.

The motivation was simple – to give parents, particularly poor parents, real power to determine the best education for their children. But the details were complex. Unless the new system was well designed and regulated, they believed, low-income children would continue to be denied a fair shake.

The professors envisioned three types of K-12 schools under a new banner of public education, all to be called “common schools.” There’d be: (more…)

This is the latest installment in our series on the center-left roots of school choice, and Part I of a series within a series about school choice efforts in late ‘70s California.

The woman stopped the professor as they were leaving church near campus.

It was the fall of 1978 in northern California, and Jack Coons was a local celebrity. Or at least as much a celebrity as you can be if you’re a legal scholar who specializes in education finance.

He and Stephen Sugarman, a fellow law professor at the University of California Berkeley, had been central figures in a series of court decisions in the 1970s that would dictate a more equitable approach to how California funds its public schools.

They had also just written a provocative book.

It called for scrapping the existing system of public education, and replacing it with one that gave parents the power to choose schools – even private schools. This stuff about “vouchers” was out there, but intriguing enough to generate some buzz. Newsweek gave it a plug.

My cousin is Congressman Leo Ryan, the woman told Coons. He’s interested in education.

Why don’t you and your wife join us for dinner?

***

It sounds crazy, but that chance encounter could have changed the face of public education in America. For one wild year in late ‘70s California, liberal activists set the stage for the most dramatic expansion of school choice in U.S. history.

Today’s education partisans have no clue it almost happened. But it almost did. And if not for some remarkable twists of fate, it might have.

In the 1960s and ‘70s, school choice was capturing the imagination of progressives who thought poor kids were being savaged by elitist public schools. Liberal intellectuals in places like Harvard and Berkeley were happy to tinker with the notion of school vouchers encapsulated by conservative economist Milton Friedman in 1955. They tried to cultivate varieties that included controls they believed necessary to ensure fairness for low-income families.

John E. “Jack” Coons and Stephen D. Sugarman were among them. And in 1978, they unexpectedly got an opening to put their vision of school choice on the ballot in the biggest state in America.

It started with the dinner invitation. (more…)