Editor’s note: This month, redefinED is revisiting the best examples of our Voucher Left series, which focuses on the center-left roots of school choice. Today’s post from December 2015 describes efforts to put school vouchers on the 1980 California ballot.

This is the all-in-one version of our recent serial about efforts to put school vouchers on the 1980 California ballot. It's part of our ongoing series on the center-left roots of choice.

The woman stopped the professor as they were leaving church near campus.

It was the fall of 1978 in northern California, and Jack Coons was a local celebrity. Or at least as much a celebrity as you can be if you’re a legal scholar who specializes in education finance.

He and Stephen Sugarman, a fellow law professor at the University of California, Berkeley, had been central figures in a series of court decisions in the 1970s that would dictate a more equitable approach to how California funds its public schools.

They had also just written a provocative book.

It called for scrapping the existing system of public education, and replacing it with one that gave parents the power to choose schools – even private schools. This stuff about “vouchers” was out there, but intriguing enough to generate some buzz. Newsweek gave it a plug.

My cousin is Congressman Leo Ryan, the woman told Coons. He’s interested in education.

Why don’t you and your wife join us for dinner?

***

It sounds crazy, but that chance encounter could have changed the face of public education in America. For one wild year in late ‘70s California, liberal activists set the stage for the most dramatic expansion of school choice in U.S. history.

Today’s education partisans have no clue it almost happened. But it almost did. And if not for some remarkable twists of fate, it might have.

In the 1960s and ‘70s, school choice was capturing the imagination of progressives who thought poor kids were being savaged by elitist public schools. Liberal intellectuals in places like Harvard and Berkeley were happy to tinker with the notion of school vouchers encapsulated by conservative economist Milton Friedman in 1955. They tried to cultivate varieties that included controls they believed necessary to ensure fairness for low-income families.

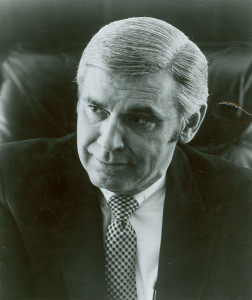

John E. “Jack” Coons and Stephen D. Sugarman were among them. And in 1978, they unexpectedly got an opening to put their vision of school choice on the ballot in the biggest state in America.

It started with the dinner invitation.

***

Cue “Staying Alive.”

Disco was king. Jimmy Carter was president. And across the bay from Berkeley, the punk band Dead Kennedys was blasting its first angry chords. But in 1978, Coons and Sugarman still hadn’t gotten the carbon-copy memo that the ‘60s were over.

The ballot initiative they detailed in their 1978 book, “Education by Choice,” wasn’t gradual change, organic growth, nibbling at the edges.

It was revolution. (more…)

This is the latest post in our series on the center-left roots of school choice.

U.S. Congressman Leo Ryan was a popular Democrat who favored school choice. In 1978, he started working with Berkeley law professors Jack Coons and Stephen Sugarman on a plan to put school choice on the statewide ballot in California. An early poll showed 59 percent of voters were in support.

All of us know Lincoln was assassinated. But not many know the twist of fate that left historians asking: What if? Had it not been for a clown of a cop named John Frederick Parker – who was supposed to be protecting the president at Ford’s Theatre, but instead slipped next door to the Star Saloon – America after the Civil War may have coursed in dramatically different directions.

The history of school choice has its own forgotten twist of fate.

It involves Berkeley law professors, a murderous cult, and U.S. Rep. Leo Ryan, a school choice Democrat. Given relentless attempts by choice critics and the press, in this age of Trump and hyper-tribalism, to portray choice as right-wing madness, it’s worth revisiting Ryan and what happened 40 years ago. Would white progressives still view choice as a Red Tribe plot had white progressives been the first to plant the flag? And in big, blue California to boot?

In 1978, Berkeley law professors Jack Coons and Steve Sugarman laid out a social justice case for school choice in “Education by Choice,” a book that also offered a detailed policy blueprint. The prevailing system of assigning students to schools by zip code, they argued, was elitist and dehumanizing to low-income families. Their sweeping alternative included private school vouchers and independent public schools (which we now call charter schools). It also included visions of a system that would allow parents to build their kid’s educational programs a la carte, like today’s education savings accounts.

In 1978, Berkeley law professors Jack Coons and Steve Sugarman laid out a social justice case for school choice in “Education by Choice,” a book that also offered a detailed policy blueprint. The prevailing system of assigning students to schools by zip code, they argued, was elitist and dehumanizing to low-income families. Their sweeping alternative included private school vouchers and independent public schools (which we now call charter schools). It also included visions of a system that would allow parents to build their kid’s educational programs a la carte, like today’s education savings accounts.

Coons and Sugarman wanted to plant seeds, not spark an instant revolution.

But then, serendipity.

Congressman Ryan, enjoying his third term representing the San Francisco Bay area, was a former public-school teacher and a product of Catholic schools. “Education by Choice” moved him. As fate would have it, his cousin went to church with Coons. So he had her invite Coons to dinner.

Ultimately, the professor and the congressman decided they’d try to get the California Initiative for Family Choice on the statewide ballot. All they needed was enough signatures. Ryan agreed to be the face of the campaign.

Choice couldn’t have found a better spokesman. Before Ryan was elected to Congress, he was a state lawmaker who practiced what one newspaper called “investigative politics,” and his aide Jackie Speier – now U.S. Rep. Jackie Speier – called "experiential legislating."

Ryan worked as a substitute teacher to immerse himself in high-poverty schools. He went undercover to experience Death Row at Folsom Prison. As a Congressman, Ryan trekked to Newfoundland to investigate the slaughter of baby seals, and even laid down on the ice to save a seal pup from a hunter.

It’s not a stretch to think Ryan’s popularity would have rubbed off on the ballot initiative.

This is the all-in-one version of our recent serial about efforts to put school vouchers on the 1980 California ballot. It's part of our ongoing series on the center-left roots of choice.

The woman stopped the professor as they were leaving church near campus.

It was the fall of 1978 in northern California, and Jack Coons was a local celebrity. Or at least as much a celebrity as you can be if you’re a legal scholar who specializes in education finance.

He and Stephen Sugarman, a fellow law professor at the University of California, Berkeley, had been central figures in a series of court decisions in the 1970s that would dictate a more equitable approach to how California funds its public schools.

They had also just written a provocative book.

It called for scrapping the existing system of public education, and replacing it with one that gave parents the power to choose schools – even private schools. This stuff about “vouchers” was out there, but intriguing enough to generate some buzz. Newsweek gave it a plug.

My cousin is Congressman Leo Ryan, the woman told Coons. He’s interested in education.

Why don’t you and your wife join us for dinner?

***

It sounds crazy, but that chance encounter could have changed the face of public education in America. For one wild year in late ‘70s California, liberal activists set the stage for the most dramatic expansion of school choice in U.S. history.

Today’s education partisans have no clue it almost happened. But it almost did. And if not for some remarkable twists of fate, it might have.

In the 1960s and ‘70s, school choice was capturing the imagination of progressives who thought poor kids were being savaged by elitist public schools. Liberal intellectuals in places like Harvard and Berkeley were happy to tinker with the notion of school vouchers encapsulated by conservative economist Milton Friedman in 1955. They tried to cultivate varieties that included controls they believed necessary to ensure fairness for low-income families.

John E. “Jack” Coons and Stephen D. Sugarman were among them. And in 1978, they unexpectedly got an opening to put their vision of school choice on the ballot in the biggest state in America.

It started with the dinner invitation.

***

Cue “Staying Alive.”

Disco was king. Jimmy Carter was president. And across the bay from Berkeley, the punk band Dead Kennedys was blasting its first angry chords. But in 1978, Coons and Sugarman still hadn’t gotten the carbon-copy memo that the ‘60s were over.

The ballot initiative they detailed in their 1978 book, “Education by Choice,” wasn’t gradual change, organic growth, nibbling at the edges.

It was revolution. (more…)

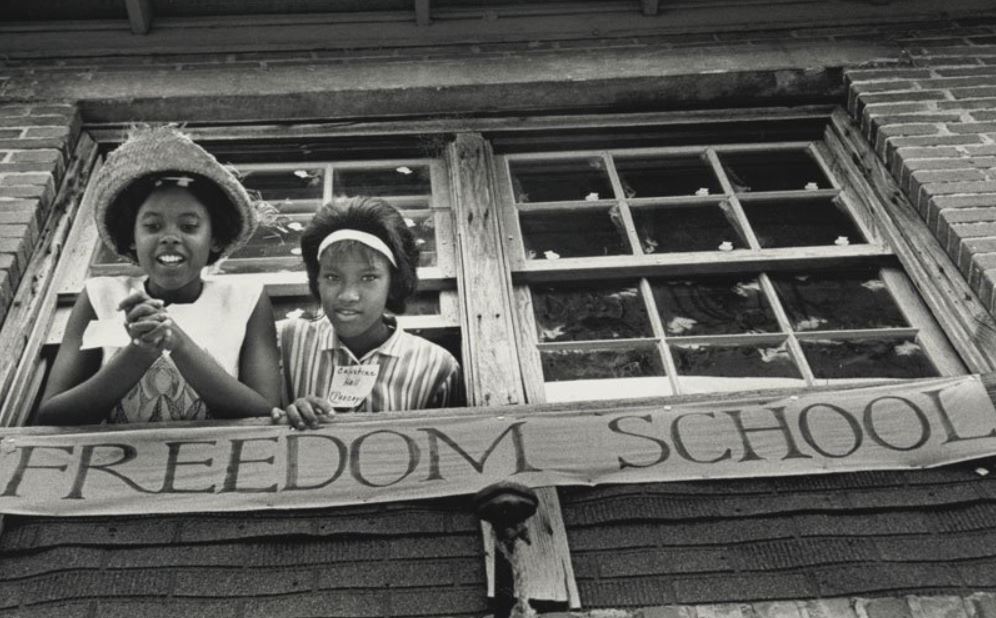

Despite what the story lines too often suggest, school choice in America has deep roots on the political left, in many camps spanning many decades. Mississippi Freedom Schools, pictured above (the image is from kpbs.org), are part of this broader, richer story, as historian James Forman Jr. and others have rightly noted. Next week, we’ll begin a series of occasional posts re-surfacing this overlooked history.

By critics, by media, and even by many supporters, it’s taken as fact: School choice is politically conservative.

It’s Milton Friedman and free markets, Republicans and privatization. Right wing historically. Right wing philosophically.

Critics repeat it relentlessly. Conservatives repeat it proudly. Reporters repeat it without question.

It has been repeated so long it threatens to replace the truth.

The roots of school choice in America run all along the political spectrum. And to borrow a term progressives might appreciate, the inconvenient truth is school choice has deep roots on the left. Throughout the African-American experience and the epic struggles for educational opportunity. In a bright constellation of liberal academics who pushed their vision of vouchers in the 1960s and ‘70s. In a feisty strain of educational freedom that leans libertarian and left in its distrust of public schools, and continues to thrive today.

This is not to deny the importance of the likes of Friedman in laying the intellectual foundation for the modern movement, or to ignore the leading role Republican lawmakers have played in helping school choice proliferate. But the full story of choice is more colorful and fascinating than the boilerplate lines that cycle through modern media. Black churches and Mississippi Freedom Schools are part of the picture. So is the Great Society and the Poor Children’s Bill of Rights. So is U.S. Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan, D-N.Y., and Congressman Leo Ryan, D-Calif., the only member of the U.S. House of Representatives to be assassinated in office.

Perception matters. Perhaps now more than ever. There is no doubt far too many people who consider themselves left/liberal/progressive and identify politically as Democrats do not pause to consider school choice on its merits because they view it as right-wing and Republican (or maybe libertarian). In these polarized times, people have never identified with ideological and party labels so completely, and, I fear, so often made snap judgements based on perceived alignments.

School choice isn’t the only policy realm to suffer from false advertising, but in the case of vouchers, tax credit scholarships and related options, the myths and misperceptions appear particularly egregious. (Note: I work for Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog and administers Florida's tax credit scholarship program, the largest private school choice program in the nation.) The forgotten history means newcomers to the debate get a fractured glimpse of the principles that have long fueled the movement. And it means critics can more easily cast contemporary supporters on the left as phonies or sellouts, as opposed to what they really are: heirs to a long-standing, progressive tradition.

We at redefinED would like to redouble our efforts to change that. So, beginning today, we’re going to offer a series of occasional posts about the historical roots and present-day fruits of school choice that are decidedly not conservative.

We’re calling it “Voucher Left.”

We hope to offer entries big and small, some by redefinED regulars, some by guests. We may rescue a historical document from the dust bin. We may serve up a profile or podcast. Maybe we’ll reconstruct some fascinating but forgotten moments in the rich history of choice, like what happened in California in the late 1970s when a couple of Berkeley law professors tried to get a revolutionary voucher proposal on the statewide ballot. (Here’s a bit of tragic foreshadowing: But for Jim Jones of the People’s Temple, vouchers today might be considered a liberal conspiracy.)

There is no set schedule for the series. We’ll roll out posts as often as time permits, and as often as we can keep digging up good stuff. Look for the first two right after Labor Day.

In the meantime, a few caveats:

We didn’t coin the term “voucher left.” As far as we can tell, all credit goes to writer (and former fellow at the Center for American Progress) Matthew Miller. In a 1999 piece for The Atlantic, Miller used the term to describe the ‘60s era choice camp that included John E. Coons and Stephen Sugarman, Berkeley law professors who co-founded the American Center for School Choice, which helped put this blog on the map. We thought the term perfect – and just as fitting an umbrella for choice’s other progressive pillars. (more…)

We liberals see our public schools as the centerpiece of America’s “melting pot” society. Religiously divisive societies like Northern Ireland and Lebanon worry us. Teachers unions are generally applauded as providing needed job protection for committed professionals who are helping to shape the lives of our children. These beliefs combine to cause all too many liberals automatically to oppose school choice plans that would enable more low-income families to choose religious or other private schools for their children. That’s too bad, and it need not be that way.

Liberals certainly think that our society should pay special attention to the needs of low-income families, often non-white families. And it is clear to everyone that all too many of the children from these families are now poorly served by conventional public schools. To remedy this problem, liberals typically put their faith in the internal reform of public education. In the meantime, however, liberals with means seem content for other people’s children to remain stuck in public schools that they would never tolerate for their own children.

Lots of low-income families also are committed to public education, and if their local schools are bad, their focus is on making them better. But other low-income families would like to choose something else for their children. Surely liberals are predisposed to respect the judgments of all families, rich or poor, as to what they believe is in the best interest of their children.

Encouragingly, in large parts of America, school choice has now become a central feature of public education. Charter schools, magnet schools, inter-district transfer programs, and the like all enroll children on the basis of family choice. A number of school districts have even converted their entire enrollment system into a family choice plan that no longer bases assignment on the location of the family’s residence. Well-to-do families have traditionally been able to “choose” their children’s public schools by deciding where to live -- especially in upper-income suburban enclaves which offer good public education to which low-income families are realistically denied access. The newer sorts of public school choice arrangements provide wider opportunities to low-income families, and liberals like President Obama support them.

Charter schools may threaten teachers unions, and they are often managed by entrepreneurs, sometimes even profit-making organizations. But they are still public schools -- open to all (by lottery, if applications exceed seats available), free of charge, and free from religion.

This is exactly the problem, however, for low-income families who want faith-based schools for their children. School choice programs, such as Milwaukee’s voucher program and Florida’s tax credit scholarship program, target these families. Through them, tens of thousands of families now can opt for something they could not otherwise afford. Most other wealthy nations also subsidize that sort of choice. Yet, American liberals are the most outspoken opponents of such plans.

This stance is inconsistent with fundamental liberal beliefs. Liberals are all for "choice" when it comes to abortion and want the government to pay for abortions sought by poor women. Why can’t more liberals see the desirability of fully extending choice to low-income families when it comes to education?

Some liberals persist in arguing that "common" public schools are necessary because they are society’s way of transmitting democracy and tolerance to everyone. This is a romanticized picture of what actually happens in public schools. Moreover, America’s private schools don’t teach intolerance. To the contrary, research shows that their students become as or more tolerant than their public school-going counterparts. Indeed, it is the closing off of private schools to those who cannot afford them that interferes with parents’ fundamental exercise of their free-speech rights when they are unable to select the educational values their children are taught.

Contrast America’s system of higher education. The federal government provides “Pell Grants” to low-income students regardless of whether they attend public or private colleges. The great private universities all provide additional tuition assistance to low-income applicants and many of the best admit on a needs-blind basis. It is left to students and their parents to decide whether or not they wish to attend a faith-affiliated college.

Liberals who personally care about religion and who send their children to religious schools often seem indifferent to the religious beliefs of parents who are too poor to make the same choice for their children. Giving vouchers or tax credit-funded scholarships to children from low-income families should be a "free exercise" issue with civil liberties organizations. Instead, these programs are miscast as an "establishment" of religion. But the right kind of school choice plan no more breaches the "wall of separation" between church and state than does the current income tax deductibility of contributions to religious organizations.

Of course, school choice by itself is not a "silver bullet" that will magically cure all our educational woes. But school choice plans can help low-income families obtain something they want for their children that even the most liberal charter school plan cannot provide -- religious education. My wife and I are not religious and we never sent (or wanted to send) our daughter to a religious school. But we could have afforded it if it had been our family preference. I consider myself a liberal, and I find it anything but liberal to automatically oppose choice plans that could empower low-income families to select for their children from among the options I had for mine.