Around the state: New superintendents were sworn in in school districts that include Sarasota and Broward, a job fair will be held to address the nationwide teacher shortage, Flagler officials are working to get new buses to replace their aging fleet and faculty are leaving New College of Florida. Here are details about those stories and other developments from the state's districts, private schools, and colleges and universities:

Around the state: New superintendents were sworn in in school districts that include Sarasota and Broward, a job fair will be held to address the nationwide teacher shortage, Flagler officials are working to get new buses to replace their aging fleet and faculty are leaving New College of Florida. Here are details about those stories and other developments from the state's districts, private schools, and colleges and universities:

Broward: Peter Licata was sworn in as superintendent of Broward schools, the sixth largest school district in the nation and the state's second largest. Licata was hired in mid-June by the school board. He was previously a regional superintendent in Palm Beach schools. WLRN. Miami Herald.

Palm Beach: Superintendent Mike Burke will be paid at least $340,000 for his leadership of about 180 Palm Beach county schools, according to a draft of his new contract for employment. The school board will vote today on the extended contract for Burke, which includes a 9.5% boost in his base salary. Palm Beach Post.

Hillsborough: Former Hillsborough County schools superintendent Addison Davis has landed a job as a partner with Strategos Group, an education management consulting firm. The move was announced on Monday, the first business day after Davis ended his 39 months as leader of the district. Davis said in a resignation letter that he wanted to return to Northeast Florida where he grew up and started his career. Tampa Bay Times.

Pinellas: Bus drivers are being sought in this county as the school year's start nears. ABC Action News.

Sarasota: The school district's new superintendent here is Terry Connor, who was sworn in on Monday during a ceremony. Connor said he wants to cut through the political turmoil that has engulfed the district and make it the country's best. Connor is a former assistant superintendent in Hillsborough county. Sarasota Herald-Tribune.

Flagler: For the first time in its history, Flagler's school board is looking to finance the purchase of 16 new school buses and buying a half dozen more every year in an attempt to modernize its aging fleet. District officials have cleared the way for its financial adviser to prepare a request for proposal that would seek bankers offers to finance a $2.6 or $2.8 million purchase of 16 buses that would be delivered during the 2024-25 school year. That would replace 16 buses that are 15 years old. Flagler Live.

Teacher shortages: With less than a month until school is back in session, officials here are facing a plight similar to districts nationwide: the teacher shortage. "There's definitely concerned with having the openings that we have," said Suzette Rivera, Director of Recruitment for the Lee County School District. There are over 400 job openings currently, which include teaching, coaching and administrative positions, officials say. Fox 4. Meanwhile, in Broward county schools needs teachers, bus drivers and more. Currently, 800 positions are open. A job fair will be held this weekend to help hire positions. CBS Miami.

Examining books: Florida is prompting schools to examine books with a statewide lens. In Leon county, Superintendent Rocky Hanna removed five titles from schools at the suggestion of the Moms for Liberty group, and in Orange county, the school district puts holds on dozens of classic and popular novels. Meanwhile, in Pasco, $3 million was spent to replace elementary classroom libraries with choices by a district-level media specialist. Tampa Bay Times.

University and college news: More than one-third of New College of Florida faculty won't be returning in the fall, according to Provost Bradley Thiessen. He called the 36 departures in a single year "ridiculously high" for a school with less than 100 full-time students. Many are teachers and researchers who saw no other option but to resign or take leave to look at other opportunities. Tampa Bay Times. The honors program at the University of South Florida will soon move from the oldest building on campus to a five-story, 85-000 square-foot building named after Judy Genshaft, USF's former president. Genshaft and her husband, Steven Greenbaum, donated $20 million for the project, which has been years in the making. The $56-million building will open to students at the end of this month. Tampa Bay Times. A University of Florida researcher has created interventions for sickle cell disease. Dr. Diana Wilkie, a UF College of Nursing researcher, is co-author of a commission report published July 11 that includes 33 co-authors comprising experts in sickle cell disease, in addition to patients and activists around the world. Sickle cell is an inherited disorder that changes red blood cells into a C shape. Main Street Daily News.

Opinions on schools: The Northwest Evaluation Association, a nonprofit research organization also known as NWEA, recently released an analysis called "Education's long COVID: 2022-23 achievement data reveal stalled progress toward pandemic recovery" show that students suffered a pronounced slowing of academic growth during the school year. This is incredibly sad but not incredibly surprising. Matthew Ladner, reimaginED.

Several weeks ago, we looked at American racial achievement gaps in math and reading from an international perspective using data from the Program for International Student Assessment, an international test that every three years measures reading, mathematics and science literacy of 15-year-olds.

In 2012, the PISA exam included subgroup specifically for Florida. Let’s take a look:

So, a couple of notes. This PISA data is from 2012. The National Center for Education Statistics shows that Florida’s white, black and Hispanic students all saw very large academic gains since the 1990s. We have reason to fear, therefore, that if the PISA exam had been given in, say, 1998, the results would have looked very frightening indeed. As it is, the results didn’t look so great in 2012.

Florida’s black students land in the vicinity of students in Chile and Mexico. Chile and Mexico spend only a fraction of what is spent per pupil in the United States and must contend with much larger student poverty challenges. Florida’s Hispanics scored higher, but still performed similar to students in Greece and Turkey, lower-spending countries.

The Third International Mathematics and Science Study exam from 2015 allows us to take a similar look at Florida subgroup achievement in international context. PISA and TIMSS test a different grouping of countries (with quite a bit of overlap) and test somewhat different things. Nevertheless, TIMSS also included Florida subgroups.

Here are the results for mathematics for nations and Florida racial/ethnic subgroups on eighth-grade math.

As was the case in the PISA data, American black students achieved similarly to students in nations that spend only a fraction of what American schools spend per pupil, and with more severe poverty challenges. Florida’s Hispanic students score higher but also find themselves outscored by countries such as Malta, Slovenia and Kazakhstan, which don’t begin to match American levels of spending. Florida’s Asian and Anglo students didn’t conquer the globe but had scores that were comfortably European if not Asian.

Make what you will of this information, but in my opinion, we have miles yet to go.

Students at Hadassah John’s school on the San Carlos Apache Reservation in Arizona participate in hands-on activities to spark curiosity. John opened the school to give families an alternative to their F-graded district public school.

I had the opportunity recently to visit a new, small private school on the San Carlos Apache Reservation in Arizona. The school illustrates an education trend that is providing a new avenue for addressing America’s largest achievement gap.

The United States has done very poorly by Native Americans, including but hardly limited to K-12 education. Starting in the late 19th century, a group of “Indian Schools” was established. Authorities forcibly separated families and attempted to forcibly assimilate students, even beating them for speaking their native language. In addition to being barbaric and illiberal, these and other federal efforts have left Native American students with the largest achievement gap in the country.

The opposite of foreigners creating schools and forcing children to attend them is to have the community create its own schools and give families the opportunity to enroll. Arizona’s suite of charter and private choice policies has been expanding these opportunities over the years, and there has been progress.

As the chart above shows, Arizona has been making greater academic progress across all student subgroups than the national average, including with Native American students. The challenges, however, remain daunting. Many reservation areas are rural and remote, making it difficult to launch and maintain charter schools. All Arizona racial/ethnic subgroups scored equal to or above the national average on eighth-grade math and reading in 2017 except Native American students. Despite the gains, these students have yet to catch up to their peers nationally, much less to those peers’ Anglo averages.

A new school on the Apache Nation, however, points to a new hope. A Democratic senator from Arizona’s Navajo Nation pushed legislation through years ago making residents of Arizona reservations eligible to receive an Empowerment Scholarship. In January 2019, a small group of these students began participating and created a new private school.

Hadassah John, the school’s teacher, attended Apache reservation schools. She became inspired to start a new school because public schools in the area were low-performing, and her students experienced bullying and a lack of academic challenge. The local school district spends well above the Arizona state average but earned a letter grade of F from the state. Parent reviews, and even a teacher review, on the Great Schools site are scathing. John felt the community needed an alternative.

“I believe a child cannot learn if, one, they do not feel safe; and two, if they are not understood. This alternative offers each child (a chance) to learn at their own pace. They do not have to feel insecure or inferior to the student sitting next to them,” John noted.

Students at John’s schools focus on hands-on projects. On the day of my tour, a visiting Stanford graduate student was assisting them with designing and printing 3-D objects. They obviously were having fun.

John, who runs the school from a church campus, has raised $5,000 to purchase supplies and technology. She hopes to add a second class of students in the fall, and despite many obstacles, may be on the forefront of a new teacher-led model of education.

In her words: “If there is no joy in what you do or believe, it is harder to carry with you. There are a lot of challenges I have faced since Day 1. I have used each challenge thrown at us as a brick to help build a bridge for students to cross from hopelessness over to success and education.”

When I shared with John that I recently heard a 44-year veteran teacher relate on a radio program that “the joy has been strangled out of the profession,” and that the problem in education is not a lack of money, she responded with a quote from Albert Einstein: “It is the supreme art of the teacher to awaken joy in creative expression and knowledge.”

From what I saw during my visit, it looks like joy is fully awake at this new school.

Two new studies illuminate Florida K-12 funding. The first, from Mike Petrilli, president of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute and research fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution, includes this chart:

So, for those of you squinting at your iPhone, the east-west axis is tracking the percent change in enrollment between 2000 and 2015, while the north-south axis is showing the constant dollar percentage increase in per pupil funding.

There obviously is a negative relationship between rapid enrollment growth and high levels of per pupil spending growth. Most of the states with very large increases saw their student population shrink. Florida looks to have seen population growth of approximately 15 percent during this period and per pupil funding growth of 18 percent.

Petrilli notes a national baby-bust, but in Florida this may simply mean a moderating of enrollment growth, already noted between older Census estimates and more recent state projections. There will be no moderation of the increase in the elderly population. A decade from now this may look like the good ole days of funding increases, so buckle up.

TaxWatch also released a study finding an “all in” per pupil number for Florida schools of $10,856. The analysis compared the traditional district school cost to the cost of two of the largest learning options the state currently provides to parents and their students – charter schools and tax-credit scholarships.

TaxWatch estimated per charter school student funding for fiscal year 2017-18 to be $7,476. The average maximum scholarship available through the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship Program, which allows children from low-income and middle-income families to attend private schools, for fiscal year 2017-18 was $6,447.

A Florida newspaper editorial board that recently editorialized that Florida “could not afford” vouchers may require some remedial math; Florida has a great deal of enrollment growth on the way and can more easily afford to choose charter and private schools than districts, although all three will remain options.

The research arm of the National Student Clearinghouse released a report recently on the number of students graduating from institutions of higher education by state. The Research Center works with higher education organizations to better inform practitioners and policymakers about student educational pathways, tracking students enrolling in a public four-year college anywhere in the country. So even if a Florida high school graduate were to do the unthinkable and enroll in, say, the University of Georgia, this system would track him or her down.

Here is how things break down for the 2012 student cohort – students who enrolled in Fall 2012.

According to a chart prepared by the National Center for Education Statistics, the high school graduating class of 2011-12 included 151,964 students in Florida; 418,664 in California; and 292,531 students in Texas – just in case you were curious.

Living out in a distant and pleasant patch of cactus, I noticed this week that Arizona overtook Florida in average teacher pay in the latest National Education Association report. ZONA! ZOZA! ZON … oh, wait. Neither state is near the top. The Florida news report on the NEA numbers contained the typical demands for additional state funding, but there is more going on here than state priorities.

Looking ahead, none of this is going to get easier as Florida turns Japanese – in other words, one of the oldest countries in the world. At some point this year, Florida’s elderly population will surpass the youth population according to estimates by Florida’s Office of Economic and Demographic Research. And the trend won’t stop.

Don’t get too excited about the percentage of young people declining, because the EDR projects the absolute numbers of school-age students will continue to increase by the hundreds of thousands – just not nearly by as many of hundreds of thousands as your elderly people.

Japan currently is sitting where Florida is heading. But should Floridians fear turning Japanese? The Japanese buy more adult diapers than baby diapers these days. Pensions, Medicaid … yeah, there is a lot to feel concerned about. Japan, however, has an advantage over most of the United States in the form of a better-educated student body, which it arrives at despite spending less money per pupil.

From the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development:

A couple of notes: The USA spends big and scores low on international exams. That’s a huge problem. Florida has been doing better than the (pathetic) American average, but the state is no Japan yet, and did you notice the part where Japan spends less than the United States but scores way better?

Okay, yeah, that needs to stop.

Finally, despite being a big spender, America does not compensate its teachers well, especially young teachers. The blame for this, however, does not lie exclusively at the state level.

The Florida Legislature is not the state’s school board. The staffing and compensation decisions of Florida public schools are determined at the local level – school boards, superintendents, principals, CFOs and a whole bunch of others budget these dollars, and those budgets include teacher pay. Given that the United States is a high-spending country, why do we have such low starting pay for teachers?

Well, in large part because of this:

Nationally, student enrollment in American public schools increased by 9 percent; non-teaching staff increased by 138 percent. I’m not here to tell you that any school can run without non-teaching staff – none can. Nor do I pretend to know what the right mix is; it probably varies. I do know this: The vast increase in non-teaching staff puts a low ceiling on what we can pay teachers.

Recently, I dug into some celebrated cases of the state’s teachers being poorly paid in the Arizona Chamber Business News. One of these cases happened before the “Red for Ed” strike, where an Arizona second-grade teacher put her paystub up on social media. A seven-year veteran, she was being paid $35,000. Yes, that was a thing, and it was awful, but it was not what it appeared.

A dive into expenditure details revealed the district spent well above the state average per pupil, and that the voters had passed a tax increase the previous year “for teachers” which mysteriously failed to reach her paycheck. Average teacher pay in this district dropped $7,885 between 2017 and 2018, but banked a healthy increase in the fund balance of carryover funds.

It is positively horrible for a seven-year teacher, especially one tasked with teaching children how to read in the early years, to be receiving such a tiny percentage of the revenue generated by her students. It is, however, *ahem* very difficult to blame this teacher’s salary exclusively on the state Legislature with a straight face.

This isn’t a matter of tweaking around the edges. Florida needs a complete re-imagining of the delivery mechanism for education. Hundreds of thousands of additional students are on the way, along with a far larger increase in elderly population. The more Japanese Florida becomes (pass the sushi over to Arizona, btw), the more acute the state’s need will grow.

There is a universe of teachers willing to work in school districts. Florida needs them. There is another group willing to work in charter schools. You need them, too. There is yet another group willing to teach in private schools. Hundreds of thousands of more kids are on the way, and there’s Grandma’s Medicaid to pay – yes, please. Then there is a group of pioneering teachers who are running their own small schools where they get to be both the teacher and the boss entirely off the bureaucratic grid.

Florida education already is far better than it used to be, and the future is brighter still. But in the years ahead, you are going to need all the help you get.

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis signed an executive order recently to transition the state away from the current academic standards, which begs the question: What will replace them? I have a suggestion on that front, but first, some basics.

Federal law requires states to have a set of academic standards and to test students against those standards in grades 3-8 and again in high school as a condition of federal funding. About a decade ago, a number of states adopted “Common Core” academic standards and tests, which eventually became quite controversial. As an education reform strategy, both center-right analysts like Erik Hanushek and center-left analysts like Tom Loveless found little prospect for broad improvement in outcomes due to adoption of the standards.

In fact, if we examine eighth-grade trends in scores since 2009, just before many states adopted the standards, to the most recent numbers, the results are decidedly less than meh, although multiple factors always are at play in influencing scores at any given time. While “meh” results square with the Hanushek/Loveless research findings, this does not preclude the possibility of states doing themselves some harm in transitioning to new standards.

Practices eliciting a great deal of controversy for ambiguous benefits don’t tend to endure. The theory of change behind the standards movement seems straightforward: States create (hopefully) an integrated set of academic standards, test students against those standards, make the results transparent to families, and perhaps reward/sanction schools based on them. If in fact it were this straightforward, we would expect to see broad improvement in a variety of academic indicators since the adoption of the strategy in the mid-1990s. But the theory-of-change bucket seems leaky. Meanwhile, much of the public has grown deeply fed up with a culture of test prep in public schools.

Supporters of academic transparency – I include myself in this category – ought to use this opportunity to consider carefully what it is we want from our system of standards and tests, how to minimize unintended consequences, and how to increase the utility of the system to students. Federal law requires states to have them, so why not adopt the best standards that any state has developed?

Massachusetts was a pioneer in the standards movement, creating standards almost a decade before the federal requirement. Massachusetts also adopted several other K-12 reforms simultaneously, so we should exercise caution in concluding that standards and testing led to the state’s improvement. Nevertheless, those standards were widely admired by scholars. Even prominent supporters of the Common Core project judged them superior to the Common Core standards.

Massachusetts has long held the highest scores in all subjects on the National Assessment of Educational Progress. We can’t be certain what they did right, but they seemed to have done something right, and it might be the standards. The reality is that there would be a large amount of overlap in a three-circle Venn diagram between the old Florida standards, the more recent Florida standards, and the old Massachusetts standards. Massachusetts may, however, have succeeded in positively influencing curriculum with its standards, which have been described as “content rich.” Color me skeptical as to whether there is either a Florida, Arizona or even (blasphemy!) Texas way to teach long division, but Massachusetts seemed to do better than others with its old standards, and in fact better than itself after adopting Common Core.

There is no issue of federal nudging or compulsion, real or imagined, at this point. Florida is entirely free to adopt whatever standards it wishes. You won’t find many areas of agreement between me and Diane Ravitch, but I think this qualifies as one: You must have standards, and Massachusetts has developed what appear to be the most useful set. Why settle for less?

My advice, not that you asked for it, is to call up the Bay State and see if anyone there can send over a copy.

When The Fellowship of the Ring was released in 2001, I was in the subset of viewers who had not read J.R.R. Tolkien’s books. Yes, right, I know: Nerd demerit! It proved beneficial as a movie-going experience, as it shocked me: Wait, what? Sarumon is a bad guy??

When The Fellowship of the Ring was released in 2001, I was in the subset of viewers who had not read J.R.R. Tolkien’s books. Yes, right, I know: Nerd demerit! It proved beneficial as a movie-going experience, as it shocked me: Wait, what? Sarumon is a bad guy??

The Gandalf vs. Saruman fight scene comes to mind when I see choice supporters who say they “support choice,” but only a particular type of choice. David Osborne’s piece in The 74 is a recent example of this genre. Osborne obviously is a sincere gentleman, but the scale of our challenges lies far beyond the ability of charter schools alone to address.

In the scene from the movie, Gandalf has gone to consult with a superior about how dire things are, only to have someone he thought was an ally inform him, “The hour is later than you think.” Come with me, dear reader, and I’ll do my best to convince you that the hour is later than we – or Osborne – thinks.

School Choice Week is an opportune time to reflect upon the enormity of our education challenges. Scholars who study educational enrichment spending, which can span Kumon/Mathnasium to club sports and drama, have produced charts like the one below. It’s well worth staring at for a good long while so it will haunt your dreams as you think through the implications.

Wealthy parents not only are sending their kids to better funded schools in the leafy suburbs; it’s not just the fact that teachers have very little control over their pay under unionized “get old and get paid” scales, causing the more effective ones to gravitate to the suburbs for easier working conditions. On top of this, those same upper-income parents are supplementing the education of their children out of their own pocket – and have been doing more and more of this for decades. Moreover, all of this is seen as so utterly and unremarkably normal that we rarely even discuss it.

In his piece, Osborne says he opposes universal education savings accounts because he fears that wealthy parents will top up the funding. I agree this is an issue to discuss, but the answer is not to doggedly stick to charter schools because we imagine them to be more equitable. Following Osborne’s logic would require one to oppose the funding of a public-school system, as the scenario he fears happening with education savings accounts has in fact been ongoing for decades in the public schools. Parents can and do supplement charter school education as well.

When we view the status quo through the lens of equity, what we see is that not only do the suburban schools get more funding; not only do wealthy parents supplement their own children to a far greater degree than poor parents; not only do their schools have an associated advantage in attracting human capital. In addition, the funds provided for the education of low-income children tend to be spent ineffectively in urban school systems.

Against all this, Osborne wants to bring charter schools to bear. I want to bring charter schools as well, but limiting ourselves to charter schools would be like the U.S. Army storming the beaches at Normandy equipped only with sling shots in the face of Nazi rifles, machine guns and artillery.

Florida policymakers have accomplished a great deal related to choice, and the vast majority of what they’ve done is universally available. No one has ever had to fill out a Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) form to forensically reveal their family income to attend a district school, a charter school or a magnet school or to enroll in Florida Virtual School. For that matter, no one ever has been denied access to a Florida college or university because his or her parents paid too much in taxes. All Floridians pay their taxes, all Floridians access publicly funded schooling options.

What, then, is to be done? We should recognize from the outset the limits of policy and aim to judge next moves not only against ideals but also against the status quo. Equity issues are very important, but let’s remember that it took everything in the second graphic above in addition to a lot of controversial non-choice related reforms and 20 years to get this in Florida:

The above chart tracks the percentage of Black eighth-graders in the United States and Florida scoring “Below Basic” in reading. In 1998, this stood as a shockingly horrifying 47 percent nationally and a stunningly shameful, far beyond sickening 56 percent in Florida. There is a lot of work to be done both nationally and in Florida, but the drop was twice as large in Florida as nationally. It isn’t nearly enough, but Floridians should be encouraged by their success thus far to take still bolder steps. Anyone willing to look the 35 percent of Florida’s Black eight-grade students in the eye to ask them to patiently wait for a charter school to open should reacquaint themselves with A Letter from a Birmingham Jail in my humble opinion.

An education savings account program open to all with a significant financial weighting represents the best choice intervention for the disadvantaged. Osborne is correct in stating that high income families would supplement such a system, but they already supplement everything else, and most everything else gives their schools more money to boot.

An ESA system can give the most to the children who start with the least through weighting. Crucially, it also would give low-income parents the opportunity to make effective use of their funds and would strongly incentivize the most productive use of incumbent resources. The education system would shift to being centered around families with service providers competing to best suit their needs, with poor families possessing more rather than less in the way of public dollars.

There’s a huge amount of inequality today, but there also is some good, and it is worth fighting for. Reaching a consensus on these issues won’t be easy. During the ratification debates for the United States Constitution, perhaps the most rollicking and momentous dialectic in human history, James Madison summed up an argument conceding the radical nature of his enterprise by writing, “Upon this you must deliberate and decide.” Just so with you, Florida. Address equity issues in the most robust fashion possible and expand opportunity to maximum extent. These things need not be in conflict. Students poorly served today have nothing to lose but their chains, and a world of opportunity to gain.

The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. helped organize the 1963 March on Washington, where he delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech, on Aug. 28. The march, and King’s 17-minute speech, helped put civil rights at the top of the agenda for reformers and facilitated passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

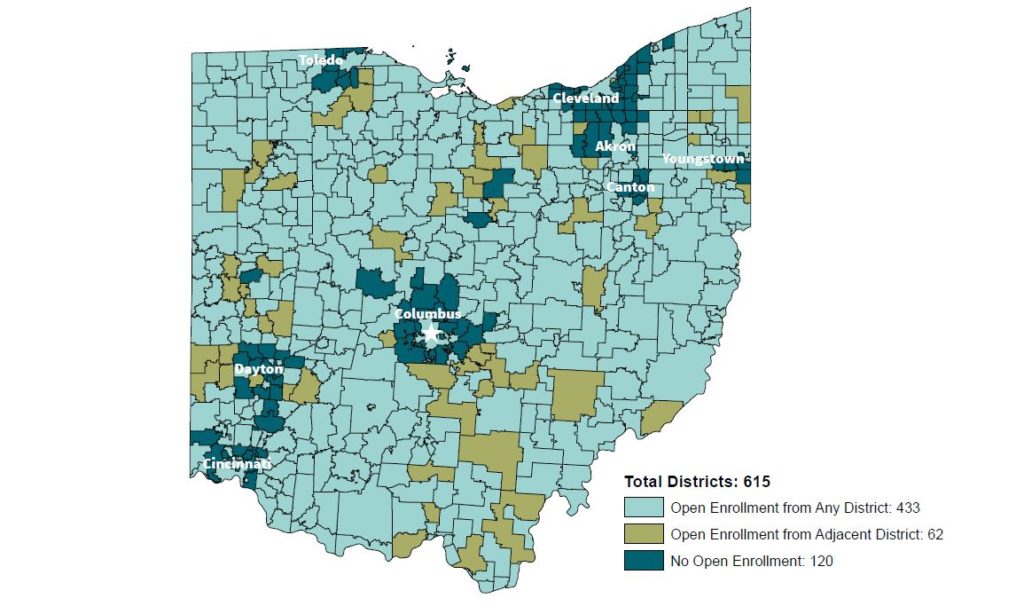

Decades after Brown v. Board of Education, a map generated by the Thomas B. Fordham Institute indicates we have miles to go regarding school integration.

The map displays 615 Ohio school districts, using color coding to show those that allow open enrollment from any district; those that allow open enrolment from an adjacent district; and those that allow no open enrollment at all. A very disturbing pattern of segregation emerges as it becomes clear that each of Ohio’s large urban districts is surrounded by districts that choose not to give students the opportunity to attend their schools.

(Keep this map in mind the next time you hear someone claim that “school districts take everyone.” Districts take every child who can afford to live in their attendance zones, which is not the same thing as “everyone.”)

Ohio is not likely a stark outlier nationally, but it is very different than my home state of Arizona, where almost all districts participate in open enrollment – including fancy suburban districts like Scottsdale. Ohio, in line with the nation, has posted flat results on the National Assessment of Educational Progress, whereas Arizona is one of two states that have made statistically significant gains on all six exams since 2009.

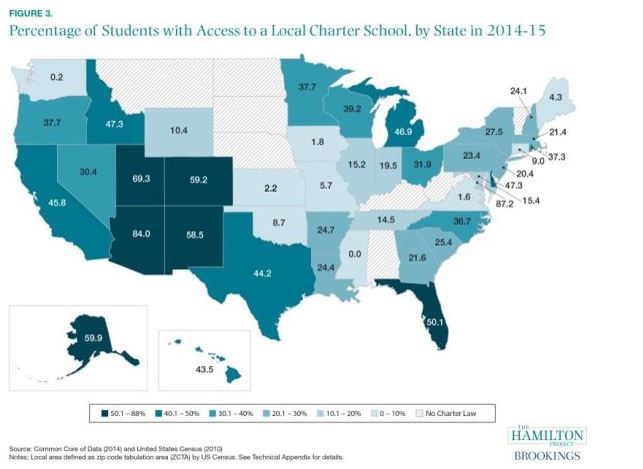

Another map, this one from the Brookings Institution Hamilton project, suggests why Ohio and Arizona are so different, and where Florida stands. This map measures the percentage of students who had access to one or more charter schools in their Zip code in 2014-15.

Arizona had the highest percentage in the nation of students with a charter school operating in their Zip code: 84 percent, which is more than two-and-a-half times higher than Ohio’s 31.9 percent. Ohio has choice options, but they are overwhelmingly clustered in urban areas, thus providing limited incentive for suburban districts to participate in open enrollment. Arizona has the highest percentage of charter school students in the country, but open enrollment students outnumber charter school students approximately two to one. One of the great contributions of Arizona’s charter and private choice policies has been to create an incentive for districts to participate in open enrollment.

Florida’s choice options, meanwhile, are more inclusive and diverse across community types than Ohio’s, and less so than Arizona’s. In 2014-15, just more than half of Florida students had one or more charter schools operating in their Zip code. Florida’s private choice programs focus on low-income families and children with disabilities. Low-income students are concentrated in large urban districts, but they are present in every district in the state, as are children with disabilities. Florida also has taken steps to increase open enrollment. This should be strongly encouraged, but in the end, incentives carry greater power than laws.

A great and counter-intuitive irony is at work here. The charter and private choice movement has been very focused on students in large urban districts. There are compelling moral reasons for this, but it may not have represented the optimal strategy for helping urban students. Urban students absolutely need access to charter and private schools, and they need it more than others. Urban students should however be able to attend suburban district schools as well through open enrollment. Only broad choice policies will incentivize districts to participate. Thus, urban students will be best served when all community types participate in choice.

The attempt to force district integration through forced busing during the 1970s caused no end of grief and ultimately ended in well-intentioned failure. Forcing families to bus their children across large distances based upon their race predictably did not go well. Progress can, however, be made through voluntary enrollments and incentives.

Prior to 1995 in Arizona, for instance, students who wished to attend a school in a different district, when allowed to do so, were required to pay tuition. Today, 4,000 students who don’t live within the boundary of Scottsdale Unified attend Scottsdale district schools free of charge. Arizona law merely requires districts to have an open enrollment policy, which could in effect mean, “buy or rent real estate here or get lost.” As a Scottsdale Unified taxpayer, I’d like to flatter myself by thinking my school district lowered the drawbridge over a suburban moat out of the goodness of our hearts. I am confident, however, that the thousands of Scottsdale students attending charter schools had a good deal to do with it.

In the end, our aim must be to increase the opportunity for families to find a school that matches the needs and aspirations of their families. We as a movement have underestimated the complexity of the interactions between different types of choice programs. Attempting to improve urban education with the suburban public schools sitting on the sidelines is akin to fighting with one arm tied behind our backs. The integrationists had a noble goal, but they pursued it with what turned out to be the wrong tools. People respond better to carrots than sticks, incentives rather than force.

The state of the education emergency in our inner cities can only be described as dire, which is exactly why we need to give the maximum opportunity and freedom possible across all types of schooling. Our policies can be configured in such a way as to open the walled gardens of our highest performing public schools and promote integration in the process. But don’t take it from me. The same idea was embedded in the words of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

“We refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity for this nation … When we allow freedom to ring – when we let it ring from every city and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God's children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, "Free at last, Free at last, Great God a-mighty, We are free at last."

We’ve reached 2019, and throughout the country, urban students still are largely not free to attend suburban district schools. Let’s speed up that day when they will be welcome.

My new year’s resolution is to do a better job explaining myself as a choice supporter. There is apparently a need for this, as evidenced by this recent Tampa Bay Times editorial piece about key players in Tallahassee in 2019. Regarding Florida’s new education commissioner, the Times opined:

Richard Corcoran

The answer to every education conundrum in Florida is not either (a) charter schools or (b) vouchers. In fact, new Education Commissioner Richard Corcoran should remember most students attend traditional public schools, that the state Constitution guarantees a “high quality system of free public schools,” and that his first order of business should be strengthening those schools, not scheming to tear them down or replace them.

This statement could be critiqued in a variety of ways, but today I’ll attempt to demonstrate that expanding educational opportunities however represents a strategy to in fact achieve a “high quality system of free public schools.” Furthermore, it seems to be working.

Florida created the nation’s first choice program for students with disabilities in 1999 with the McKay Scholarship Program. Students with disabilities have had the option of applying for a scholarship to attend a different public or private school statewide since 2001. Rather than representing a scheme to “tear down or replace” public schools, the statewide performance for students with disabilities improved faster than the national average. Florida lawmakers (wisely) further expanded options for students with disabilities in 2015 by creating the Gardiner Scholarship Program-the nation’s second Education Savings Account program.

This seems to be working out relatively well for Florida students with disabilities, the vast majority of whom continue to attend district schools. For you incurable skeptics, things pretty much look like Florida and the 49 dwarves when it considering both gains and overall scores for students with disabilities:

And reading:

Students with disabilities in Florida public schools have had access to full state funded choice since 2001. Students with disabilities have also had access to the other forms of choice-charter schools, the Florida Virtual School, that all Florida students can access, but in addition to that, they have had the option of attending a private school with the state money following the child. The Florida tax credit program provides opportunities for low-income students but is limited by the amount of funds raised and has a waitlist. Florida’s students with disabilities have had the most robust set of choice options for the longest period.

When we compare the gains of student with disabilities (and the fullest access to choice programs) to students without disabilities on all the NAEP exams given consistently since 2003 it looks like this:

Ten points approximately equals an average grade level worth of progress on these NAEP exams (for instance we’d expect a group of 9th graders to do 10 points better than they had as 8th graders). The technical term to describe those red columns: HUGE! In fact, if Florida’s statewide gains had matched those of students with disabilities since 2003, Florida would have matched or beat NAEP champion Massachusetts on all four NAEP exams in 2017.

Impossible you say? Many would have said those academic gains for students with disabilities were impossible in 2003, nevertheless they happened.