Summit-Questa Montessori School serves toddlers through eighth-graders on a 10-acre campus in Davie, Florida.

Editor’s note: This post from Judy Dempsey, founder and longtime principal of Summit-Questa Montessori School in Davie, Florida, is based on a chapter from her 2016 book “Turning Education Inside Out: Confessions of a Montessori Principal.”

Judy Dempsey

Education today must establish different goals for itself compared to generations ago. Today’s world is an inconsistent place that continues to change at a mind-boggling pace. Technology has transformed our world in a way that would be unrecognizable to our ancestors.

The extraordinary thing is that it may be unrecognizable to us in the near future.

In the past, education prepared students for a familiar and predictable world; the goal was to have students memorize a set of facts or learn specific skills that would serve them well in a variety of careers. Today, in the Information Age, any fact that a student would need or want is at the tip of their finger, a mouse click or screen tap away.

As educators, it is imperative that we prepare our students for the unique demands that the 21st century world will place upon them. It is vital in this age to teach students how to find the knowledge they need – knowledge as varied as the changing times themselves. Students must be able to think outside of the box and be creative learners and problem solvers.

Upon entering the workplace, they will need to work in the global community, so it is imperative for them to know how to communicate well and get along with others. They must be respectful of other cultures and traditions since it’s likely, in any business transaction, that their clients and the team with which they work will be from somewhere else in the world.

The statistics also indicate that people will change jobs much more frequently than ever before. Young people who can adapt to new and changing needs and expectations will be the ones getting and keeping the available jobs.

Our world is facing a multitude of challenges at different levels: environmentally, socially, ethically, politically, and economically. We need young people who have the skills to face unprecedented situations in the world. These are very different skills necessary for success in the 21st century and for the survival of our culture, planet, and species. When parents ask me, “Will Montessori prepare my child for the real world?”, I confidently respond by saying, “Montessori will, without any doubt, prepare your child much better than traditional education ever could for this new real world.”

If you look at all the previously mentioned skills necessary for success in the 21st century, they are all inherent in the Montessori experience. Children learn to think differently based on their unique perception of the world. They learn how to get along with classmates from different cultures, ages or genders, or perhaps a very different type of learner, thinker, and problem solver.

Exposure to these different personalities, abilities, and individual gifts allows children to develop skills that are different from their traditional counterparts. Their vocabulary, critical thinking, social, and communication skills increase with every year that they are in the Montessori classroom.

They learn to explore their own interests and the Montessori materials at their own pace. The Montessori teacher will always guide the students along the path of learning, not by providing the answers, but by constantly asking the child the questions needed to stimulate critical thinking and discovery. A Socratic questioning type of approach allows students to develop and expand their own learning and critical thinking skills.

As much as our world has turned into a machine/technology-dominated society, social skills are still highly important for success. The highest paying jobs today demand people who are not only competent with technology, but also have strong people skills—an important human trait. Social skills are not usually part of the curriculum in traditional schooling. Michael B. Horn, co-founder of the Clayton Christensen Institute, said, “Machines are automating a whole bunch of things so having the softer skills, knowing the human touch and how to complement technology is critical, and our educational system is not set up for that.”

Although these skills may not be taught in traditional schools, they are a fundamental part of the Montessori experience. In a Montessori interactive and ever-changing classroom, students learn to communicate, adapt, and problem solve in socially appropriate ways as they navigate the classroom.

That classroom is like a sea full of unique and beautiful creatures, all with their own needs and interests. As the day flows, they all learn to share their habitat, enjoy each other’s company and beauty, negotiate, and sustain the peaceful atmosphere. In the process, their own gifts grow and flourish, contributing to the overall health of the environment.

Contrary to some who believe that Montessori classrooms are chaotic and nonstructured, where students can do whatever they want with no responsibility, nothing could be further from the truth. Students are expected to be responsible community members, finish the work that they choose, and return it to the shelf so that someone else can use it.

They mentor each other and care about each other. They collaborate, thereby learning to be more productive as a team. They trust each other and work on sharing their strengths with each other for the good of all. Our Montessori students are very well prepared for the 21st century.

President Barack Obama stated on CBS news, “I’m calling on our nation’s governors and state education chiefs to develop standards and assessments that don’t simply measure whether students can fill in a bubble on a test, but whether they possess 21st century skills like problem-solving and critical thinking and entrepreneurship and creativity.”

Remarkably, those in the traditional world of education do indeed have this important information; however, implementing a system that incorporate these skills into their classrooms remains a mystery to them. The National Education Association has been working for many years to bring innovation into public school systems. Its educational researchers have long recognized that students need to acquire very different skills for the future and have narrowed the focus to the “Four Cs.”

They name these Four Cs: communicators, collaborators, creators, and critical thinkers. Sounds familiar, doesn’t it? It also is interesting to note that while we’ve had the Montessori education system successfully in place worldwide for more than 100 years, few policymakers and educators take our approach seriously.

The American Management Association in a 2010 survey on critical skills stated:

“The Four Cs will become even more important to organizations in the future. Three out of four executives who responded to the survey said they believe these skills and competencies will become even more important to organizations in the next three to five years; additionally, 80% believe that reading, writing and arithmetic are not sufficient if employees are unable to think critically, solve problems, collaborate, or communicate effectively.”

I could continue to cite dozens and dozens of additional resources that give the same message about the importance of many other skills beyond reading, writing and arithmetic that our students need today. It should be obvious to anyone familiar with the Montessori approach that Montessori has been doing this the entire time it has been in existence. There is no doubt how timely it is today in preparing our students for the world in which they will find themselves as adults.

Dr. Maria Montessori, ever the visionary, was able to understand what our students would need for their future.

Brody Cholnik, 5, struggled with virtual prekindergarten but is showing promise as a kindergartner at the Wesley Chapel Montessori School at Lexington Oaks. His mother, Nicole Cholnik, chose to send him to a private school so she and her husband, rather than the public school district, will be able to make the decision to have Brody repeat kindergarten if necessary.

Editor’s note: During the holiday season, redefinED is reprising the "best of the best" from our 2020 archives. This post originally published Nov. 4.

Even after eight months of pre-kindergarten, Brody Cholnik struggled to learn his ABCs. Regular sessions with a private tutor and supplemental lessons at home helped, but Brody’s mother suspected something beyond her control was in play.

Her 4-year-old’s birthday wouldn’t come until several months after many of his classmates already had turned 5. She worried that it put him at a disadvantage. On top of that, Brody’s pre-kindergarten was held in the day care he attended as a toddler and he was accustomed to it being a setting for play.

“It was hard for him to transition from a play atmosphere to a school atmosphere,” Nicole Cholnik said.

Then last spring, just when Brody began showing progress, COVID-19 hit. The tutoring center closed. His pre-kindergarten class made a hasty retreat to Zoom. And Brody, who was still two months away from blowing out the candles on his 5-year-old birthday cake, fell further behind, prompting Cholnik to wonder: What if my son needs to repeat kindergarten?

When school officials told her that decision rested with the principal, not with her and her husband, Cholnik took matters into her own hands. She transferred Brody to a private Montessori school, a move that allows her to maintain control over her son’s fate when he turns 6 and is required by state law to be enrolled in school.

"If we decide as parents that he's not ready for kindergarten, then next year when he goes to (his zoned school) he can do kindergarten again," said Cholnik, who lives in a suburb just north of Tampa. "Or, if we feel he's prepared enough and ready for first grade, we can give them the certificate of completion and put him into first grade."

A controversial but growing trend

A parent’s choice to delay kindergarten, commonly called “academic redshirting,” became a hot topic in academic journals in the early 2000s. Author, journalist and public speaker Malcolm Gladwell put redshirting on the public radar in 2008 with his bestselling book “Outliers,” championing the practice and arguing that the practice made a difference in a student’s long-term success.

Over the years, redshirting has been argued about in countless parenting blogs, journals and news stories, with critics saying it can harm children later in school.

There are many pieces in play. Research indicates the phenomenon tends to happen more frequently in white families, and more often with boys than girls. Because redshirting can require families to pay for an extra year of day care or kindergarten fees, it’s more common among those whose incomes fall in the middle or upper brackets, prompting equity concerns.

One argument supporters make in favor of redshirting is that when families hold children back a year, the child then likely will be the oldest and possibly most mature in his or her class, and therefore possibly more able to successfully compete in academics and sports.

Redshirting has taken on a new prominence in the COVID-19 environment as schools nationwide began reporting falling enrollments, especially in the kindergarten ranks, with the start of the 2020-21 academic year. According to an NPR survey of 100 school districts, the average kindergarten enrollment drop was 16%.

The survey attributed the decline partially to the emergency pivot to online learning in the spring. The negative experiences left some families dissatisfied and in search of other options, especially in districts that started the new school year 100% online. One parent of a 5-year-old boy in Texas told NPR she had concerns regardless of whether the school opened online or in-person because an in-person experience was going to be “weirdly socially distanced and masked.”

Though the parent chose not to delay kindergarten for her son, she did send him to a private school where masks were optional and class sizes were smaller.

High stakes for empty seats

Some Florida school districts experienced enrollment declines as well, especially in the early grades. An October student count in Palm Beach County showed enrollment for pre-kindergarten through 12th grade in district schools at 187,776, the lowest level since 2016.

Kindergarten saw the biggest hit, with a decrease of 1,416 students, or 12%, compared with the previous fall. The figures prompted district chief financial officer Mike Burke to speculate that parents were delaying their children’s entry into school. It also caused district leaders to begin worrying how the enrollment decline would affect education funding for the district.

Though local property taxes contribute to education funding, districts depend on per-student funding based on the number of students occupying seats. At the start of the 2020-21 school year, districts were able to shield their funding by striking a deal with the state that allowed them to maintain pre-pandemic funding levels in exchange for reopening brick-and-mortar campuses. That deal expires at the end of first semester, leaving administrators bracing for draconian funding cuts in the spring.

‘A tough conversation’

For the Cholniks and other families who are sitting it out this year, learning is still happening, although it may be unique ways, such as reading books together at home and playing with Nerf guns, or enrolling in a private kindergarten that gives the parents the option of having their child take a second shot at kindergarten next year.

Brody has made progress at his private school, but Cholnik predicts he will end up having to repeat kindergarten. In the meantime, she has scheduled testing to see if he has a learning disability. If tests uncover an issue that has “a simple fix,” there’s a chance Brody could move on to first grade next year.

But Cholnik would rather have Brody repeat kindergarten than enter first grade behind his peers, and eventually have to repeat fourth grade if he fails the standardized test the state requires for public school promotion.

“That would be a tough conversation to have at that age,” she said. “That’s why we’re taking this route now."

Moumin Elgizoli, 4, paints with his class as part of a virtual preschool pilot program, a partnership formed in response to parent demand between Denver Public Schools and the taxpayer-supported Denver Preschool Program.

Editor’s note: This post by Chandra Thomas Whitfield published earlier this month on Chalkbeat.

Sara Mohamed and her husband had intended to enroll their 4-year-old son in in-person preschool at Holm Elementary, a nearby Denver public school, but as COVID-19 infection rates soared through the fall in Colorado, they had second thoughts.

They placed their two older children into virtual learning but struggled to find a district program for their preschooler.

“All summer he’d been excited about going to school in the fall; he was so ready to go,” said Mohamed, of Denver. “He was so disappointed when we eventually told him that he would not be able to go to school in person.”

The family’s saving grace came when a call to Mile High Early Learning, a network of nine subsidized Montessori-inspired learning centers in Denver, confirmed they had space in its virtual preschool pilot program.

The program stems from a partnership between Denver Public Schools and the taxpayer-supported Denver Preschool Program, in response to parent demand. Unlike some other Colorado school districts, Denver Public Schools originally did not offer a virtual preschool option. Administrators there believe strongly that in-person learning is better for the youngest students.

It wasn’t quite the “big boy school” experience Mohamed and her family had envisioned for their energetic little Moumin, but they quickly concluded that any help getting him kindergarten ready was worth a try. Mohamed says weeks into the program her son is flourishing, and they’re grateful to have him enrolled.

“He’s so happy, he loves it,” said Mohammed, who supports new Arabic-speaking families and teaches English classes virtually for Holm Elementary. “It’s only 30 minutes a day, but it’s still made a big difference for him. He can’t wait to log in at 3:30 p.m.”

Mile High Early Learning and the Denver Preschool Program said the pilot appears to be working well for enrolled families.

Mile High Early Learning is among 47 providers that had enrolled in the pilot as of Dec. 3, according to Denver Preschool Program President and CEO Elsa Holguín. Some providers are offering remote learning while some are planning virtual programs in case they have to pivot later in the school year.

Mile High Early Learning students log in Monday through Thursday with program-issued iPads preloaded with learning apps, to join a teacher and more than a dozen classmates for 30 minutes. Families also receive books, paper, crayons, markers, and art supplies. The program asks parents to engage their students outside of class in drawing, painting, writing letters, and even homework.

Holguín says the pilot aims to support early childhood education providers. Since the onset of the pandemic, many said they felt like they were, “flying by the seat of their pants,” with limited guidance and direction.

“We decided that the best thing to do was not just to continue to help out our providers, but also to figure out how to start learning more about how to do [distance learning] at a quality level,” Holguín said.

Denver Preschool Program has underwritten sliding-scale tuition and teacher training and coaching, and provided funding to help sites remain afloat as they navigate the challenges of the pandemic.

Mohamed says she believes the program, especially the tuition support and supplies, is a lifesaver especially for working parents who are leery about risking in-person schooling but also want to ensure their children don’t miss out on critical learning opportunities.

“We were so worried that he might get behind,” she said. “We wanted to make sure that he was ready to go to school next year.”

Occasional technical glitches aside, Mohamed says their program experience has been virtually problem-free. They’ve noticed improvements in Moumin’s attention span. She said he’s grown more focused and engaged with each session he joins with his teacher and classmates.

Rebecca Kantor, a Denver Preschool board member who sits on the task force that is developing the distance learning curriculum, said the group sought to incorporate best practices in early childhood education.

“The two most important things that we know about young children’s learning is that they learn through direct experience and they learn within the context of stable trusting relationships,” said Kantor, dean of the School of Education and Human Development at the University of Colorado Denver. “So, we’re trying to recreate that using tech as a tool and we’re really getting very creative in figuring out a lot of different ways to do that.”

For example, she said, one suggested activity entails a student and parent painting together at home, while a teacher discusses with them on screen.

“One of the benefits of doing it that way is that the adult at home is also learning effective conversation skills from the teacher,” she said. “So, there’s a modeling going on that’s really good for the adults, too.”

Mile High Early Learning President and CEO Pamela Harris said along with providing a solid foundation in academics, administrators and teachers in the program have incorporated critical social and emotional learning opportunities.

“Even babies can develop true relationships using technology,” said Harris, who also co-chairs Colorado’s Early Childhood Professional Development Advisory Working Group. “I think it’s the interactivity that is key, having an adult person kind of on both sides, helping the child navigate.” The pilot also provides families resources on a YouTube channel and videos.

The pilot program, which is scheduled to run through the end of this school year, will begin enrolling some 3-year-old programs starting Jan. 4

“We still believe that we need to increase the quality of the distance learning experiences in Colorado,” Holguín said.

Brody Cholnik, 5, struggled with virtual prekindergarten but is showing promise as a kindergartner at the Wesley Chapel Montessori School at Lexington Oaks. His mother, Nicole Cholnik, chose to send him to a private school so she and her husband, rather than the public school district, will be able to make the decision to have Brody repeat kindergarten if necessary.

Even after eight months of pre-kindergarten, Brody Cholnik struggled to learn his ABCs. Regular sessions with a private tutor and supplemental lessons at home helped, but Brody’s mother suspected something beyond her control was in play.

Her 4-year-old’s birthday wouldn’t come until several months after many of his classmates already had turned 5. She worried that it put him at a disadvantage. On top of that, Brody’s pre-kindergarten was held in the day care he attended as a toddler and he was accustomed to it being a setting for play.

“It was hard for him to transition from a play atmosphere to a school atmosphere,” Nicole Cholnik said.

Then last spring, just when Brody began showing progress, COVID-19 hit. The tutoring center closed. His pre-kindergarten class made a hasty retreat to Zoom. And Brody, who was still two months away from blowing out the candles on his 5-year-old birthday cake, fell further behind, prompting Cholnik to wonder: What if my son needs to repeat kindergarten?

When school officials told her that decision rested with the principal, not with her and her husband, Cholnik took matters into her own hands. She transferred Brody to a private Montessori school, a move that allows her to maintain control over her son’s fate when he turns 6 and is required by state law to be enrolled in school.

"If we decide as parents that he's not ready for kindergarten, then next year when he goes to (his zoned school) he can do kindergarten again," said Cholnik, who lives in a suburb just north of Tampa. "Or, if we feel he's prepared enough and ready for first grade, we can give them the certificate of completion and put him into first grade."

A controversial but growing trend

A parent’s choice to delay kindergarten, commonly called “academic redshirting,” became a hot topic in academic journals in the early 2000s. Author, journalist and public speaker Malcolm Gladwell put redshirting on the public radar in 2008 with his bestselling book “Outliers,” championing the practice and arguing that the practice made a difference in a student’s long-term success.

Over the years, redshirting has been argued about in countless parenting blogs, journals and news stories, with critics saying it can harm children later in school.

There are many pieces in play. Research indicates the phenomenon tends to happen more frequently in white families, and more often with boys than girls. Because redshirting can require families to pay for an extra year of day care or kindergarten fees, it’s more common among those whose incomes fall in the middle or upper brackets, prompting equity concerns.

One argument supporters make in favor of redshirting is that when families hold children back a year, the child then likely will be the oldest and possibly most mature in his or her class, and therefore possibly more able to successfully compete in academics and sports.

Redshirting has taken on a new prominence in the COVID-19 environment as schools nationwide began reporting falling enrollments, especially in the kindergarten ranks, with the start of the 2020-21 academic year. According to an NPR survey of 100 school districts, the average kindergarten enrollment drop was 16%.

The survey attributed the decline partially to the emergency pivot to online learning in the spring. The negative experiences left some families dissatisfied and in search of other options, especially in districts that started the new school year 100% online. One parent of a 5-year-old boy in Texas told NPR she had concerns regardless of whether the school opened online or in-person because an in-person experience was going to be “weirdly socially distanced and masked.”

Though the parent chose not to delay kindergarten for her son, she did send him to a private school where masks were optional and class sizes were smaller.

High stakes for empty seats

Some Florida school districts experienced enrollment declines as well, especially in the early grades. An October student count in Palm Beach County showed enrollment for pre-kindergarten through 12th grade in district schools at 187,776, the lowest level since 2016.

Kindergarten saw the biggest hit, with a decrease of 1,416 students, or 12%, compared with the previous fall. The figures prompted district chief financial officer Mike Burke to speculate that parents were delaying their children’s entry into school. It also caused district leaders to begin worrying how the enrollment decline would affect education funding for the district.

Though local property taxes contribute to education funding, districts depend on per-student funding based on the number of students occupying seats. At the start of the 2020-21 school year, districts were able to shield their funding by striking a deal with the state that allowed them to maintain pre-pandemic funding levels in exchange for reopening brick-and-mortar campuses. That deal expires at the end of first semester, leaving administrators bracing for draconian funding cuts in the spring.

‘A tough conversation’

For the Cholniks and other families who are sitting it out this year, learning is still happening, although it may be unique ways, such as reading books together at home and playing with Nerf guns, or enrolling in a private kindergarten that gives the parents the option of having their child take a second shot at kindergarten next year.

Brody has made progress at his private school, but Cholnik predicts he will end up having to repeat kindergarten. In the meantime, she has scheduled testing to see if he has a learning disability. If tests uncover an issue that has “a simple fix,” there’s a chance Brody could move on to first grade next year.

But Cholnik would rather have Brody repeat kindergarten than enter first grade behind his peers, and eventually have to repeat fourth grade if he fails the standardized test the state requires for public school promotion.

“That would be a tough conversation to have at that age,” she said. “That’s why we’re taking this route now."

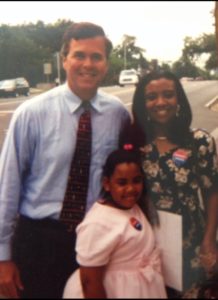

Tracy James, foreground, and her daughter, Khaliah Clanton-Williams, are greeted by principal Maria Mitkevicius and administrator Mary Gaudet at the Montessori School of Pensacola. Khaliah was one of the first students to use Florida's "first voucher," the Opportunity Scholarship, in Fall 1999. PHOTO: Michael Spooneybarger

Editor's note: 2019 marks the 20th anniversary of the far-reaching K-12 changes that Gov. Jeb Bush launched in Florida, including creation of the first, modern, statewide private school choice program in America. To highlight those changes, redefinED embarked upon a series of articles that examine Bush's "education revolution" and how it continues to reverberate. Today's piece spotlights a mom and daughter who participated in Florida's historic Opportunity Scholarship.

PENSACOLA, Fla. – Tracy James finished the graveyard shift to find her car a casualty of the “voucher wars” – and her 8-year-old, Khaliah, needing another ride to school.

This was 20 years ago, when this Deep South Navy town became the front in the national battle over school choice. In June 1999, Florida’s new governor, Jeb Bush, had signed into law the Opportunity Scholarship, the first, modern, statewide, K-12 private school voucher in America. Khaliah and 56 other students in Pensacola were the first recipients, and now enmeshed in a political clash drawing global attention.

CNN came. A Japanese film crew showed up. So did a member of British Parliament. All wanted to see the “experiment” a Canadian newspaper said “will shape the future of public education in this state and perhaps across the United States.” Tracy and Khaliah were in the thick of it, with Tracy among the most outspoken of an unconventional cast of characters. The single mom with the self-described rebel streak wouldn’t hide her joy at this opportunity for her only child – and refused to cave to anybody who suggested she was being “bamboozled.”

“If you want something better for your children,” she told one paper, “you would do the same thing.”

Not everybody appreciated her resolve.

Tracy walked out of her shift as a phlebotomist to find her car sabotaged, three tires flat as week-old Coke. She called her dad, who said he could take Khaliah to her new school, one Tracy could not afford without the scholarship. The flats left Tracy shocked and ticked – and more determined.

I guess I need tougher skin, she thought. Because we ain’t going back.

***

Lots of folks know Ruby Bridges. But Khaliah Clanton-Williams? Maybe one day.

The original Opportunity Scholarship students, their parents, and the five private schools that welcomed them have never gotten their due. After an epic legal battle, the Florida Supreme Court ruled the school choice program unconstitutional in 2006, and the decision in Bush v. Holmes seemed to close the chapter. But it didn’t. Many of those whose lives were touched by the scholarship have untold stories, with some still unfolding in ways that attest to the power of that experience.

In one sense, the Opportunity Scholarship was as small-scale as it was short-lived. Students were eligible if their zoned public schools earned two F grades in a 4-year span, and in 1999 only two schools – both in Pensacola – fell into that category. At the same time, most private schools sat it out. Among other restrictions, the law barred them from charging tuition beyond the scholarship amount of $3,400 to $3,800. At its height, the Opportunity Scholarship served 788 students.

And yet, it loomed so large. Florida’s “first voucher” stirred the imagination about what could be with a more pluralistic, parent-driven system of public education. It exposed the festering dissatisfaction many parents had with assigned schools. It enabled and amplified voices that still aren’t heard enough.

Pensacola may be best known for its Blue Angels and sugar-sand beaches. But most of the parents who applied for the school choice scholarships were working-class black women – nursing assistants and bank tellers, cooks and clerks, Head Start workers and homemakers. They had a lot to say about schools in Pensacola’s low-income neighborhoods, and for a few months in 1999, they had the mic.

***

Khaliah’s assigned school was modest red brick, five blocks from her home, named for the district’s first “supervisor of colored schools.” Khaliah would be starting kindergarten, so Tracy stopped to visit. She never got past the front office. “It was a zoo,” she said. “Kids were running around. They were screaming. There was no discipline. There was no structure.”

Nobody with the school acknowledged her, so after a few minutes, Tracy left … for good. She turned to her only option: another district school near her mother’s house, two miles away. Tracy said her mom, a former custodian for the school district, became Khaliah’s guardian so Khaliah could attend. But that school didn’t pan out either.

One day, Tracy watched through a window as kids in Khaliah’s class danced to music blaring from a boom box. She found the teacher in a side office and asked what was going on: “ ‘She said, ‘It’s reading time.’ I said, ‘They’re not reading.’ “ Tracy opened her eyes wide for emphasis.

Khaliah, meanwhile, shy and soft-spoken, was falling behind. “I had a hard time concentrating because it was so loud,” she said. “I’d ask for help and it was like, ‘just a moment.’ But the moment never came.”

Tracy heard about Opportunity Scholarships while working another job as a hotel desk supervisor. Some guests asked her in passing about local schools, and as fate would have it, they were lawyers with the Institute for Justice, the firm that would later help defend the scholarship in court.

Ninety-two students applied for the scholarships, including Khaliah, who had come back to live with Tracy. That exceeded the available seats in the four Catholic schools and one Montessori that opted to participate, so a lottery was held.

Khaliah emerged with a golden ticket.

***

Tracy took her time before deciding on a school. She read up on Catholic schools, talked to friends and co-workers who attended Catholic schools, learned everything she could about Montessori. She was intrigued by the latter – by the mixed-age classrooms, the cultivation of creativity, the curriculum that was so different. In the end, the rebel and her daughter decided they wanted different.

Khaliah Clanton-Williams, left, used an Opportunity Scholarship to attend the Montessori School of Pensacola from second through seventh grades. She and her mother, Tracy James, revisited the school last week for the first time in years. PHOTO: Michael Spooneybarger

Khaliah attended Montessori School of Pensacola from second through seventh grade, and, in Tracy’s words, “blossomed” in confidence and knowledge. She returned to public school in eighth grade (Tracy wanted her re-acclimated to public school before high school) and graduated from Pensacola High in 2010. For most of the next few years, she worked as a mortgage loan officer. She earned her associate degree in business administration from Pensacola State College in 2018. She’s on track to earn a bachelor’s in human resources management (with honors) in 2020.

Without the Montessori, Khaliah said, much of that would not have happened.

“It made me better,” she said. “I don’t think I would have gone to college. I don’t think I would have gotten my degree. (Montessori) made education more important. It was a higher standard.”

The upside wasn’t just academic. Tracy and Khaliah said nearly everyone in the school embraced Khaliah as family. There were only a few black students before a few more enrolled with the scholarships, but race was not a divide, they said. Khaliah made fast friends. They invited her to sleepovers, to ride horses, to U-pick blueberries. “These things were normal to them, but not to me,” she said.

Montessori co-owner (and head of elementary and middle school) Maria Mitkevicius said increasing diversity was a big reason the school opted into the scholarship program. So was the belief the school shouldn’t be limited to parents of means.

The staff knew the stakes, even if they didn’t know how much things might change. Twenty years after five private schools and 57 kids cracked the door, at least 26 private schools in Escambia County (Pensacola is the county seat) participate in Florida’s K-12 school choice scholarship programs, serving at least 2,163 students. Statewide, 2,000 private schools serve more than 140,000 scholarship students, with thousands more on the way.

“We thought this might change the face of education,” Mitkevicius said. “I guess it did.”

***

The news on Pensacola TV showed 10,000 sign-waving students and parents, marching at a 2016 school choice rally in Tallahassee with Martin Luther King III. As Khaliah watched it again last week, tears fell.

It hurt, she said, to see so many who still don’t have choice or fear their choices could be taken from them. At the same time, how nice to see strength in numbers.

“Back then,” she said, meaning 1999, “it was just us.”

Tracy James and her daughter, Khaliah, with former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush circa 1999. Bush championed creation of the Opportunity Scholarship program, which allowed Khaliah to attend a private school. PHOTO: Courtesy of Tracy James

Remembering back then is tough for Tracy too. Some in Pensacola’s black community could not understand why black parents would support anything connected to Jeb Bush. “We were looked on as kind of those people who are being arm twisted by the governor, like you’re letting the Republicans bamboozle you,” said Tracy, now a clinical recruiter for a Pensacola hospital.

It got ugly. Dirty looks. Heated words. The tires. Tracy said some friends and family stopped speaking to her, and she switched jobs because she felt she was being harassed for taking a stand.

But the rebel has no regrets.

“I wanted to try something different, I wanted to be different, I wanted a different opportunity for my daughter,” Tracy said. “From what I saw happening, I wanted to be able to make the choice, myself, of where she’d end up as an adult.”

“I had no idea that it’d turn out to be such a controversial issue,” she continued. “To be thrown into sort of the limelight of a political battle, I had no idea. I had absolutely no idea how important it would be.”

Or how much of a struggle.

“When we went through that program, I was thinking that was kind of the end of an era,” Tracy said. “But it was actually the beginning.”

***

The shy girl who helped pioneer school choice is now a tough-minded mom who needs more.

Khaliah is married to a paper mill machine operator, and their oldest, Kyrian, will begin kindergarten this fall. His zoned school is one of 11 D-rated schools in the district, so like her mom before her, Khaliah looked for alternatives. She applied to three higher-performing district schools through an open enrollment program, but all were full. On a second go-round, Kyrian got into a new elementary north of Pensacola. It’s not ideal. The drive will be up to 45 minutes each way, and Khaliah switched jobs – to drive for Shipt, Lyft and Uber – so she can have flexibility.

Still, she’s worried. Kyrian has special needs – he’s hyperactive, averse to change in routine and undergoing speech therapy – but has not been formally diagnosed with anything. At this time, he wouldn’t qualify for any of Florida’s private school scholarships.

The irony isn’t lost on Tracy and Khaliah. School choice helped them. They helped pave the way for more. Yet 20 years later, there still isn’t enough choice for Kyrian.

The rebel’s daughter said that just means the work isn’t done.

“I’ll continue to fight for my children as my mom fought for me,” Khaliah said. “I’m not taking no as an option.”

Teaching customized to the developmental needs of each child has been the dream of K-12 educators for over a hundred years. When I was in graduate school in the 1970s, we talked continuously about the need to abandon the one-size-fits-all, assembly-line instruction that permeated public education. But we didn’t know how to translate our ivory-tower talk about customization into real-world action.

We know education choice is a necessary but not sufficient condition for achieving excellence and equity in public education. Our goal is for every child to have access to effective, efficient customized instruction in schools, at home and in their communities. Choice is a pitstop on the road to customization.

In the early 1990s, I was a teacher union representative on a statewide commission studying how to improve Florida’s public education system. We proposed reorganizing the system around standards-based, customized instruction, but quickly abandoned the idea after teachers across the state rebelled at a series of public hearings. The teachers said we were naïve and out of touch with classroom realities. While their language may have been a bit harsh, they were correct. Our proposals were impractical. In 1992, public education was still not prepared to meet the unique needs of each child.

Thanks to emerging new technologies and policies, perhaps that time has come. Public education may finally be ready to implement customized instruction in ways that weren’t possible in earlier eras. The inability to scale has historically been the downfall of progressive efforts to move beyond one-size-fits-all instruction. In a country with 56 million PreK-12 students, instructional methods that are highly effective but not scalable have little systemic impact. A good example is Montessori programs. Many students would benefit if they had access to Montessori-based instruction. The first Montessori school opened over 100 years ago and yet, as of 2013, only about 125,000 US public school students were enrolled in Montessori programs. (more…)

School grade concerns: The Seminole County School Board is urging Gov. Rick Scott to suspend the issuing of grades this school year due to concerns about the reliability of the Florida Standards Assessment tests. Superintendents around the state have been arguing that school grades issued using results from the new tests will be unfair and inaccurate. Orlando Sentinel.

School grade concerns: The Seminole County School Board is urging Gov. Rick Scott to suspend the issuing of grades this school year due to concerns about the reliability of the Florida Standards Assessment tests. Superintendents around the state have been arguing that school grades issued using results from the new tests will be unfair and inaccurate. Orlando Sentinel.

Charters and grades: State Sen. Kelli Stargel, R-Lakeland, proposes a bill that would prohibit charter schools from denying admittance due to a student's previous academic performance. Gradebook.

Charter school query: Mason Classical Academy is being investigated by the Department of Children and Families for alleged "mental injury" and "inappropriate supervision." The Collier County charter school was founded by two school board members. Naples Daily News.

Unions and Supreme Court: The Florida Education Association could become a model for teachers unions if the U.S. Supreme Court ends the collection of union agency fees in the Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association case. A decision is expected in 2016. Education Intelligence Agency.

Education behind bars: States should do more to educate young people in jail, the Justice Center at the Council of State Government argues after surveying services in all 50 states. (more…)

Editor's note: This is a sidebar to Monday's profile post about Daniel and Suzette Dean, a Tampa, Fla. couple whose private school is at the heart of their community development vision.

At Bible Truth school, Lizzie Bilogo-Nguema, 12, helps 3-year-old Delilah Prevot with math. The school features a lot of interaction between students of different ages.

The big girl scooched the little one gently back to the center of the chair, then pointed to the work sheet on the table. Today’s topic: kindergarten math. Can you count the elephants in the first clump, Lizzie, 12, asked Delilah, 3. Now in the second clump? Now can you add them? Beneath the rainbow of clasps in her braids, Delilah correctly counted the answers out loud.

“Good job. You got it,” Lizzie smiled. “Do you know how to write a 10?”

Scenes like this play out all the time at Bible Truth Ministries Academy. The tiny private school in Tampa, Fla. often goes out of its way to put students of different ages together and frequently to have older kids teach younger ones. That kind of multi-age, multi-grade set-up isn’t unheard of – it’s a fundamental part of Montessori schools, for example – but in the case of Bible Truth, the origin of the idea is noteworthy.

A think tank called the Evolution Institute recommended it. Bible Truth followed up. And the fact that the entities have a warm relationship is a sign that bridge-building is possible even in that tense place where schools, faith and science collide.

“We get so caught up in the vessel. It doesn’t matter to me” where good ideas come from, said Daniel Dean, who co-founded Bible Truth school with wife Suzette. “If it makes sense, it makes sense.”

“It starts with, what do they want for the children and the families? – which is what I want,” said Jerry Lieberman, who co-founded the institute and has known the Deans for seven years. “We both want them to have an excellent education, and we both want to remove obstacles that stand in their way.”

The school doesn’t teach evolution. Lieberman doesn’t dwell on it.

But as its name suggests, the little institute with a board full of top-notch scientists is big on it. Its mission is to use evolutionary science to solve real-world problems. In education, that translates, in its view, into classroom practices that echo the way children have adapted to learn – in mixed-group settings, with lots of physical movement, with an emphasis on self-directed play.

The group’s co-founder and president, David Sloan Wilson, an internationally respected evolutionary biologist, carved out “10 simple truths” about childhood education from an evolutionary perspective. A lot of it hinges on choice, community, cooperation. In the Binghamton, N.Y. school district a few years ago, the 10 points were converted into classroom practices and tested in a year-long program for at-risk 9th and 10th graders. The result: Students in the program outperformed their peers in a control group. They had less absenteeism, higher standardized test performance – and a 30-point jump in the scores behind school grades.

The institute is hoping to secure funding to test the program in other school districts, and in both public and private schools.

In the meantime, it’s been working informally with Bible Truth. (more…)

Editor's note: Dionne Ekendiz founded the Sunset Sudbury School in South Florida. In her own words, here's why she did it.

I always wanted to become a teacher and make a difference in the lives of children. I truly believed in public education and wanted to be part of making it better. But like many “smart” students, I was dissuaded from that career path, especially by my math and science teachers. They encouraged me to do something “more” with my life, so I went off to MIT and pursued a degree in engineering. After 12 years as an engineer, computer programmer, and project manager in the corporate world, I finally had the confidence and courage to make a change. Others thought I was crazy to leave a great career, but I was driven to pursue my own passion.

I entered a master’s of education program and sought to get the most of my experience there. When I heard about a professor who was conducting research in the “best” public schools in the area, I volunteered to be his graduate assistant. This took me into the schools twice a week. I loved working with the students, but there were things I didn’t like about the environment. One of the most disturbing was how teachers and aides would yell at students to “stay in line” and “don’t talk” in the hallways. Those were the times that schools felt most like prisons to me. But still, I believed a good teacher could learn to control his/her students in a more humane way, so I didn’t let it bother me so much.

I entered a master’s of education program and sought to get the most of my experience there. When I heard about a professor who was conducting research in the “best” public schools in the area, I volunteered to be his graduate assistant. This took me into the schools twice a week. I loved working with the students, but there were things I didn’t like about the environment. One of the most disturbing was how teachers and aides would yell at students to “stay in line” and “don’t talk” in the hallways. Those were the times that schools felt most like prisons to me. But still, I believed a good teacher could learn to control his/her students in a more humane way, so I didn’t let it bother me so much.

A year into my education program, I gave birth to my first child. Watching her grow and learn on her own, especially during her first years, made me see the true genius inside her. Indeed, it is a genius that exists in all children. She was so driven to master new skills like walking, talking, and feeding herself. I was always there with love, support, and encouragement, but my instincts told me to stay out of her way as much as possible and let her own curiosity guide her. Because of my own experiences with schooling and well-meaning teachers, I was determined to let my daughter make her own choices. I knew that with curiosity and confidence intact, she could do and be anything she wanted to.

It slowly dawned on me that everything I was learning about teaching was contrary to the philosophy I was using in raising my own daughter. The goal of teachers, in the traditional setting, is to somehow stuff a pre-determined curriculum into students’ heads. Some teachers do it more gently than others and make it more fun, but the result is the same. Teachers must stifle their students’ own interests and desires to meet the school’s agenda. Simply put, regardless of how nice a teacher is, s/he must coerce students into getting them to do what s/he wants them to do. What I was once willing to do to other people’s children, I wasn’t willing to do to my child. That was a huge wake-up call for me. (more…)

Virtual schools. Lawmakers open online learning to more providers, including private interests, reports the Miami Herald. StateImpact Florida and the Florida Center for Investigative Reporting obtain internal emails and a recording of a K12 Inc. company meeting that they say shed light on questionable company practices involving teachers who are not properly certified.

Struggling schools. The Broward school district will overhaul five struggling schools by closing some and revamping others, reports the South Florida Sun Sentinel. Principals are key to turning around five struggling Pinellas schools, reports the Tampa Bay Times.

Struggling schools. The Broward school district will overhaul five struggling schools by closing some and revamping others, reports the South Florida Sun Sentinel. Principals are key to turning around five struggling Pinellas schools, reports the Tampa Bay Times.

Tutors. The Tampa Bay Times looks at the last-minute legislative scrap over whether to continue state-mandated tutoring for low-income kids.

Private schools. Voters in Palmetto Bay will get to vote on whether a local Montessori can expand. Miami Herald.

Rick Scott. Teacher pay raise tour comes to an end, reports the Tampa Bay Times. Will it get him any votes? asks the Palm Beach Post. (more…)