Editor’s note: redefinED guest blogger Jonathan Butcher wrote this commentary for Fox News Network and offered it to redefinED for republication.

Editor’s note: redefinED guest blogger Jonathan Butcher wrote this commentary for Fox News Network and offered it to redefinED for republication.

Parents looking for a national consensus on whether schools should open in the fall won’t find one. But that’s okay. We don’t need one.

As soon as President Trump announced his support for reopening schools, teacher unions said he was “brazenly making these decisions.” So much for consensus. And this despite the fact that both proclamations said students should be kept safe, emphasized Centers for Disease Control guidelines on reopening (speakers on the White House panel cited no fewer than eight CDC reports, while unions called the documents “conflicting guidance”), and claimed to have the nation’s best interests in mind.

Well.

Luckily, many state officials and school leaders had already moved on. In April, Montana Gov. Steve Bullock said that schools could hold classes in-person immediately but left the decision to local educators. In Idaho, closures varied by school district, but some school leaders had students back in class by May. Governors and state officials have announced in-person summer school classes for Illinois, Pennsylvania, Nevada, Texas and Virginia.

Even if relatively few schools have thus far decided to have students return to the classrooms, that fact that some states have done so should change parents’ question from if schools will open in the fall to how quickly the process can happen.

“The CDC has issued guidance,” Vice President Mike Pence said at the White House event, “but that guidance is meant to supplement and not replace state, local, territorial, or tribal guidance.” What may be “conflicting guidance,” to unions is better described as “federalism.” 50 states, 50 different pandemics, 50 laboratories of democracy.

That’s the way it should be. Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis coined the “laboratory” phrase, prefacing it by saying, “To stay experimentation in things social and economic is a grave responsibility.” We should be encouraged, then, that some local educators are not waiting for Washington to decide for them, and, likewise, that parents are not waiting on schools.

After the wild ride of sudden school closures in March, uneven attempts at online instruction through the spring, and a school year that seemed to have no official end date, polls showed more parents were considering educating their children at home. For those wondering if the 59 percent of respondents in a USA Today/Ipsos poll who said they may homeschool now really meant it, a headline last week—and weeks before school starts—from North Carolina’s North State Journal read “Homeschool requests overload state government website.”

Those not ready to homeschool will find it difficult if not impossible to return to work if schools are closed. Montana is not Virginia which is not New York City, and parents ready to homeschool in Greensboro, N.C., may be thinking differently than a family in Charlotte. Parents should be wary of press releases with advice on education from public or private national groups that use words like “comprehensive,” “nation’s schools,” or even “all.”

The Trump administration said that schools may lose federal money if they stay closed. Such a move would likely be challenged in court. But one problematic aspect of this threat is that it keeps the debate over who should be making decisions for the “nation’s schools”—again, beware the phrase—at the national level, a tussle between the federal government and nationally-focused special interest groups.

A more effective talking point for the administration would be to encourage the laboratories. For example: In areas where schools are closed, state lawmakers could give parents and students who wish to opt-out of those schools the students' per-student spending amount to use for homeschooling resources, private school tuition, tutors and more. Or erase district boundaries and allow students to choose a traditional school other than his or her assigned school.

The National Education Association and American Federation of Teachers, the nation’s largest teacher unions, will howl at the suggestions, but they should be loath to take the matter to court again. Last week, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Montana could not prevent families from choosing a religious school when students use K-12 private school scholarships created by state law.

Unions regularly cite provisions in state constitutions that are rooted in religious bigotry when the groups sue to block such opportunities, but the High Court called precisely this language discriminatory in Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue, weakening the union’s position in 37 other U.S. states with similar provisions. The fight has already advanced to defending scholarships to religious private schools in Maine.

Washington should not force schools to reopen. But national officials can remind state lawmakers and parents there are alternatives. Short of a consensus on opening schools in August, that is the best news for everyone.

Doug Tuthill is president of Step Up For Students, which helps administer the nation's largest private school choice program (and co-hosts this blog).

The term “for-profit” has been weaponized in public education by teachers unions and their tribal allies.

They wield it against education improvement initiatives they oppose, especially education choice programs not covered by collective bargaining agreements. (Choice programs not operating under collective bargaining, such as Florida’s Voluntary PreK program, are not targets of for-profit attacks.)

For-profit corporations are forbidden to operate charter schools in Florida and California. Yet these schools are constantly being attacked for profiting off students. The overwhelming majority of Florida private schools serving tax credit scholarship and voucher students are non-profit, but newspaper editorial boards regularly criticize them for making profits.

These critics seem unfazed by the reality that district schools could not function without the products and services purchased from for-profit corporations. School buses, desks, instructional software, hardware, interactive whiteboards, books, pencils, pens, copy machines and paper are all purchased from for-profit companies. School buildings are constructed by for-profit companies using materials purchased from for-profit corporations. A proposed law requiring school districts to purchase products and services only from nonprofit organizations would be fiercely opposed by school districts, who would correctly see this as an attempt to destroy public schools.

Despite their for-profit criticisms, teachers unions rely on the profits they make from for-profit businesses to help pay their bills. During my tenure as a Florida teachers union leader, we sold insurance and financial services to teachers through various for-profit businesses. I still use a National Education Association credit card through a for-profit venture involving the NEA, MasterCard, and Bank of America.

The NEA’s for-profit businesses are not illegal. Nonprofits can own for-profit businesses provided the profits from those businesses are used for nonprofit purposes. My hometown paper, the Tampa Bay Times, is a for-profit company that is owned by the Poynter Institute, a nonprofit which provides professional development opportunities for journalists.

While teachers unions’ criticisms of for-profit businesses in public education may be disingenuous, ensuring taxpayers get the best possible value from education products and services purchased with public funds is important. But requiring that services teachers unions don’t like, such as charter schools, be purchased only from nonprofit organizations is not the best way to serve the public good. The best way is through effective contracting and oversight by government agencies.

When state government or a local school board purchases services, they should focus on maximizing the public’s benefits, not on the characteristics of the providers. As a taxpayer, I don’t care if a provider is gay or straight, male or female, black or white, for-profit or nonprofit. I want children to receive great services for a fair price. Focusing only on quality and price may not further the political agendas of certain advocacy groups, but it does serve taxpayers and the people receiving these services.

Determining what constitutes the best services for the best price is often challenging in public education. An afterschool tutoring program, a neighborhood district school, or a Montessori charter school may work well for some students, but not others.

The legendary management consultant, W. Edwards Deming, defined quality as customer satisfaction and not goodness, because what is good for one person may not be good for another. This is why parental empowerment and education choice are essential for helping determine what constitutes quality in public education. Empowering parents and educators to customize each child’s education is the best way to maximize the public’s return on its public education spending.

Given the proliferation and necessity of for-profit organizations in public education, attacking those that aren’t covered by teachers union collective bargaining agreements would seem a flawed political strategy. But it works with people and organizations who are part of the same political tribe as teachers unions, most notably many daily newspapers, Democratic politicians, and liberal advocacy groups.

As more low-income, minority, and working-class families participate in education choice programs, I hope teachers unions and their political allies will become more open to seeking common ground with these families. Many of these families are struggling to break the cycle of generational poverty. Hypocritical attacks on for-profit organizations providing services to school districts and state governments are not serving the greater good. We need to focus our collective energy on how to efficiently deliver educational excellence and equity to every child.

This is the latest post in our series on the center-left roots of school choice.

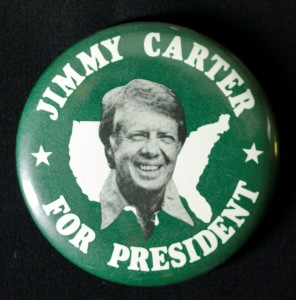

Jimmy Carter once touted school vouchers, telling readers of Today's Catholic Teacher in 1976: "While I was Governor of Georgia, voters authorized annual grants for students attending private colleges in Georgia. We must develop similar, innovative programs elsewhere for non-public elementary and secondary schools if we are to maintain a healthy diversity of educational opportunity for all our children." (Image from Wikimedia Commons)

The confirmation fight over new U.S. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos has at least temporarily pulled Congressional Democrats from the growing bipartisan consensus on school choice. But this political showdown, and the extent to which it was animated by the teacher unions, is not new.

We can probably trace its beginnings to Jimmy Carter. It was during Carter’s presidency that intraparty politics began to pry the Democratic Party from its embrace of school choice. A couple of letters from Carter to Catholic educators, four years apart, captures the shift.

In September 1976, then-candidate Carter wrote to Today’s Catholic Teacher. (Go to page 11 here.) He praised Catholic schools; referred to the “right” of low- and middle-income Americans “to choose a religious education for their children;” and argued for school choice in terms of opportunity and diversity, as pro-choice progressives had long done. He said he was committed to finding “constitutionally acceptable” ways to provide financial assistance to parents whose children attend private schools. And, as a kicker, he gave a thumbs up to vouchers:

In September 1976, then-candidate Carter wrote to Today’s Catholic Teacher. (Go to page 11 here.) He praised Catholic schools; referred to the “right” of low- and middle-income Americans “to choose a religious education for their children;” and argued for school choice in terms of opportunity and diversity, as pro-choice progressives had long done. He said he was committed to finding “constitutionally acceptable” ways to provide financial assistance to parents whose children attend private schools. And, as a kicker, he gave a thumbs up to vouchers:

“While I was Governor of Georgia, voters authorized annual grants for students attending private colleges in Georgia. We must develop similar, innovative programs elsewhere for non-public elementary and secondary schools if we are to maintain a healthy diversity of educational opportunity for all our children.”

Carter’s pro-choice, pro-voucher position is fascinating for all kinds of reasons. Today’s left has no clue about its own past support for school choice. And as the Carter letter shows, choice wasn’t some fringe phenomenon on that end of the spectrum.

It’s also fascinating because Carter changed his tune at the end of his term, a turnabout that generally marked the beginning of the left’s resistance to choice (at least the white left) and a shrinking of that common ground we’re seeing again, post-Trump. As Doug Tuthill has written, that late ‘70s flip-flop has everything to do with the rise of the teachers union as a force within the Democratic Party, and little to do with progressive values.

The key point on the timeline is 1976, when the National Education Association (NEA) endorsed a presidential candidate for the first time. That would be Carter.

Four years later, his administration scrambled to write a follow-up to Today’s Catholic Teacher. Republican nominee Ronald Reagan had written a first-person letter to the magazine, and the magazine let Carter’s people know their initial response – a statement from the administration – paled in comparison. “HURRY HURRY HURRY,” one of Carter’s media liaisons urged the PR team in a memo: “This message conceivably could be in every Catholic publication in every Catholic school.”

The team shifted into high gear. But the resulting letter surely didn’t fire up undecided Catholics.

It gave Catholic schools credit for playing a “significant role” in educating “millions of low and middle income Americans.” But instead of a continuing commitment to find constitutionally acceptable ways to provide aid to private school parents – which Carter promised in 1976 – the president would only commit to supporting constitutionally appropriate steps to get Catholic schools “their equitable share of funds provided under our federal education programs.” Clearly, a far lesser goal.

Documents in the Carter Presidential Library show what was scrubbed during editing. David Rubenstein, then one of Carter’s domestic policy advisers, nixed language that said Carter reported the administration’s efforts to help private schools to the Democratic Party platform committee. He also scratched out Carter’s support for platform language that backed tax aid for private school education. “Definitely NO,” he wrote next to the strike-through. “I don’t see any advantage to getting into the Platform,” he commented in another memo.

Also removed was a description of parochial schools that said “in many areas, they provide the best education available.” And wording that said without such schools, millions of Americans “would have been denied the opportunity for a solid education.”

Caught between the Reagan Revolution and teachers unions, Democratic support for school choice faded for a decade. It began to pulse again in the 1990s, with the advent of charter schools. Then it slowly branched into other choice realms, nudged by advocacy groups that worked tirelessly to build bipartisan and nonpartisan bridges, and welcomed by Democratic constituencies who liked having options.

That middle ground has been steadily growing, and Florida is a prime example. A few months ago, the Sunshine State elected two pro-school choice Democrats to Congress. A year ago, the state Legislature expanded America’s biggest education savings account program with universal bipartisan support. For the past two and a half years, a remarkably diverse coalition battled legal efforts to kill the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship, which now serves nearly 100,000 kids. Three weeks ago, it won.

Masses of energized parents, most of them black and Hispanic, helped fuel that legal victory. That force wasn’t in place when Jimmy Carter followed the path of least resistance. But it’s here now, and Democrats can only ignore it for so long.

On Sept. 17, 1976, the NEA endorsed Jimmy Carter for president – the first presidential endorsement in the organization’s history. With this endorsement, it joined with the other major teachers union, the American Federation of Teachers, to become a dominant force in the Democratic Party. Image from the Schell Collection.

This is the latest post in our series of the center-left roots of school choice.

Much of the opposition to private school choice seems to emanate from the Democratic Party, but this wasn’t always the case. Just look at the party platforms.

From the 1964 to 1984, the Democrat Party formally supported the public funding of students in private schools.

The 1964 platform stated, “New methods of financial aid must be explored, including the channeling of federally collected revenues to all levels of education, and, to the extent permitted by the Constitution, to all schools.” The 1972 platform supported allocating “financial aid by a Constitutional formula to children in non-public schools.” The 1976 platform endorsed “parental freedom in choosing the best education for their children,” and “the equitable participation in federal programs of all low- and moderate-income pupils attending all the nation's schools.”

Thanks to the influence of U.S. Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan, a New York Democrat and devout Catholic, the party’s 1980 platform stated “private schools, particularly parochial schools,” are an important part of our country’s educational system. It committed the party to supporting “a constitutionally acceptable method of providing tax aid for the education of all pupils.” In 1984, the platform again endorsed public funding for “private schools, particularly parochial schools.”

Then the shift began. The 1988 platform was silent on the issue, and by 1992 the Democrats had formally reversed position, stating, “We oppose the Bush Administration's efforts to bankrupt the public school system — the bedrock of democracy — through private school vouchers.”

The party’s current position on school choice was formalized in 1996. That year’s platform endorsed the expansion of public school choice, including charter schools. But it also reiterated “we should not take American tax dollars from public schools and give them to private schools.”

The Democratic Party’s shift from supporting to opposing public funding for low-income and working-class students in private schools can be traced back to an event that also helped spur the growth of modern teachers unions: The 1968 teachers strike in New York City.

This strike pitted the low-income black community of Ocean Hill-Brownsville in Brooklyn against the primarily white New York City teachers union. The issue was whether local public schools would be controlled by the Ocean Hill-Brownsville community or by a city-wide bureaucracy. The union vehemently opposed decentralization since its business model was built around a one-size-fits-all collective bargaining agreement with centralized management.

The strike lasted from May to November 1968. Given school districts are usually the largest employer in most communities, union power quickly grew. (more…)

This post first appeared on the Friedman Foundation blog.

Social movements such as women’s suffrage, black civil rights, and parental choice in education involve the redistribution of social, political, and economic power. Because few groups in control of that power at the time are enlightened enough to share it voluntarily, these power struggles are usually contentious—but they don’t have to be.

Although school choice opponents have used name-calling, character assassination, and misinformation as key strategies in maintaining their power, thankfully they have refrained from the physical violence that often accompanies disruptive social change. The bad news is their strategies still undermine our civic discourse and make it more difficult to provide every child with an equal opportunity to succeed. Our children and our democracy deserve better.

Despite the opposition’s tact, school choice supporters should try engaging opponents, particularly teachers’ unions. I know that is easier said than done, but, in the long run, the willingness to search for common ground could accelerate the transition to greater school choice. I say this as someone who’s had a front-row seat on both sides of this debate.

I became a teachers’ union organizer in 1978, and, for the next 16 years, held a variety of local, state, and national leadership positions in both the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) and the National Education Association (NEA). Today, I am president of a nonprofit organization that helps administer our nation’s largest private school choice program.

Although neither side is without sin, I have been most disappointed by the discourse coming from the teachers’ unions and their anti-choice allies. When I talk with local, state, and national union leaders, I am stunned at how uninformed they are and how many falsehoods they have embraced as truths.

I recently had dinner with one of our country’s top teachers’ union leaders who told me there has never been research showing students benefit from school choice programs. And last month, I was on a panel with a top Miami-Dade union leader who erroneously said Florida’s tax credit students are not tested.

This level of ignorance is a reflection of how insular, polarized, and tribal our politics have become. People are increasingly retreating into self-contained echo chambers where they hear only the messages that reflect the positions of their political tribe. Without access to contrary views from sources they know and trust, people have no basis upon which to question the one-sided communications they are receiving. And few organizations are as insular and tribal as teachers’ unions.

Such insularity causes many union leaders to develop a mindset that says their positions are good and all contrary positions, and those who hold them, are evil—hence all the rhetoric coming from teachers’ union leaders.

There are also financial incentives at play. (more…)

Everyone in the debate over how best to improve public education has private interests. Our collective challenge is to manage these often conflicting interests in ways that best serve the common good.

We all have private interests.

People pursuing their private interests – individually or as a group – is what drives progress and innovation. But our private interests should never trump the common good.

Private interests usurping the public good is privatization. Privatization is bad. It undermines democracy and progress.

Encouraging the pursuit of private interests while avoiding privatization is a core challenge for our economic and political democracy. In pursuing their private interests, individuals and organizations often claim their interests promote the common good, while the interests of those they disagree with don’t. Politics derives, in part, from conflicting claims of whose private interests better align with the common good.

We see this regularly in our debates over how best to improve public education.

As a long-time teacher union leader, I sold financial services, insurance and advocacy services to teachers working for school districts. Therefore, maximizing the number of teachers employed by school districts served my business interests. Our union continuously asserted that more teachers working for school districts served the common good, as did higher teacher salaries and benefits. Our favorite marketing slogan was, “Teachers’ working conditions are students’ learning conditions.”

Our union’s political and marketing strategy was to tie the private interests of district teachers to a greater common good (i.e., the welfare of children). Of course, the private interests of teachers are often – but not always – tied to children’s interest, so this was, and still is, an effective strategy.

Teacher unions use a similar political strategy when attacking school choice programs that empower students and teachers to attend schools not covered by union contracts. The unions accuse these schools of furthering privatization. As the National Education Association recently stated about charter schools not under union contracts: “We oppose the creation of charter schools for the purpose of privatization.”

Teacher unions are often criticized – unfairly in my opinion – for advocating for the private interests of district teachers. (more…)

Editor's note: This is the fourth and final post in a series on the future of teachers unions.

Over the last 20 years, the federal government and state governments have used standards, assessments and regulatory accountability to assert more top-down control over classroom teachers. As state-mandated teacher evaluation and merit pay systems have become ubiquitous, the level of teacher disempowerment and alienation has soared, and teacher unions have hunkered down and become even more defensive and conservative.

School choice is the way out - not only because it is breaking down public education’s 19th Century industrial management model, but because teacher unions are so economically tied to this model they are fighting to preserve it, even though it is bad for teachers and students. Ironically, teacher union dues today are used to perpetuate a dysfunctional management system, and to protect teachers from being abused by this same system. It’s crazy.

I say this as a former teacher union leader.

I started teaching in fall 1977. In January 1978, I sat at a table with other teachers and heard a divorced mother with two young children tearfully tell us she had rejected her boss’ sexual advances and now he was ending her employment contract. At the time, we didn’t have a union or a union contract.

I was 22 years old and became a union organizer while sitting at that table. We organized ourselves, collected cards and successfully petitioned the state to hold a collective bargaining election. We won a court case management had filed to block the election. Then we won the election and bargained and ratified a contract that included protections against arbitrarily firing employees.

In 1984, I joined a more mature union (and the school choice movement) when I moved to St. Petersburg, Fla. to help start one of the state’s first magnet schools. The Pinellas Classroom Teachers Association had been a professional association for several decades before turning into an industrial union in the late 1960s. By 1984, its collective bargaining agreement had been in place for more than a decade, and it had established a collaborative working relationship with management.

After the intensity of building a union from scratch, PCTA felt stagnant. The union was part of district management. It did a great job protecting teachers from the abuses of a politically-managed bureaucracy, but there was no energy or vision for progress. PCTA’s only internal and external message was, “We need more money.”

Pinellas teacher salaries increased by an average of 45 percent from 1981 to 1986, yet teachers were still miserable. More money was great, but they wanted greater job satisfaction. Individuals become teachers because they want to make a meaningful contribution to children’s lives, but that’s difficult - and often impossible - in a mass production bureaucracy that treats teachers like assembly line workers and students like identical widgets.

We attempted reform from within. (more…)

Editor's note: This is the third of four guest posts on the future of teachers unions.

by Gary Beckner

We are at a critical crossroads on the path to education reform in America. Stakeholders from all walks of life and political stripes are beginning to understand that in order to compete in a global economy we must focus on choice and technology to prepare our students for the future.

Likewise, we must also recognize that in order to drive needed change in instruction we must also examine how the teacher workforce is represented. Just as a one-size-fits-all system is not working for students, a labor union model solely fixated on protecting the status quo is no longer serving the needs of all educators in a modern workforce.

Choices in education have opened up avenues for advancing the teaching profession like never before. Virtual schools, technology, and non-traditional charter schools allow teachers to set new schedules and adapt their vision for education to a school that meets their specific needs. These innovations have brought new experienced professionals into the profession and have allowed other talented educators the ability to stay on in different capacities.

According to a membership survey by the Association of American Educators, the non-union teacher organization that I lead, teachers support laws that advance choice and promote options. For example, 68 percent of member educators support an Indiana law that provides a tax credit to parents who send their children to a private or parochial school of their choice. Similarly, 74 percent of survey respondents support Arizona's Empowerment Scholarship Accounts, which allow parents of special-needs students to use state education dollars in a school that meets the student's needs.

Despite this groundswell of support from educators themselves, the nation’s largest teacher unions, the National Education Association and the American Federation of Teachers, continue to stand in the way of commonsense education reform for the sake of preserving their own monopoly. Not only is this harmful to America’s students, it degrades the professionalism of one of the most revered career choices. (more…)

Two years ago, we launched redefinED in an attempt to help opinion leaders, the public and the mainstream media understand how public education is being transformed and redefined. So the following lead in yesterday’s New York Times was, even if by mere coincidence, gratifying to read: “A growing number of lawmakers across the country are taking steps to redefine public education … legislators and some governors are headed toward funneling public money directly to families, who would be free to choose the kind of schooling they believe is best for their children, be it public, charter, private, religious, online or at home.”

We are still early in this transition from a one-size-fits-all assembly-line model of public education to an approach that stresses empowerment, diversity and customization, but this shift to expanded school choice is accelerating and it’s inevitable. And as these changes unfold, redefinED will continue to aspire to be a place where thoughtful people can - with civility and mutual respect - discuss how best to address all the challenges this transformation is producing.

In the 1980s and '90s, when the National Education Association was a leader in trying to improve public education, we use to say change is inevitable but improvement is optional. This is especially true today, which is why the dialogue we’re having at redefinED is so important.

Thanks for staying with us.

My holiday wish is for teacher unions to expand their business model to include all public education teachers, and not just those employed by school districts.

The industrial model of unionism that teachers borrowed from the auto and steel workers 50 years ago assumes a large number of employees working in a centralized, command-and-control management system. Unions lose money when they apply this industrial unionism to smaller, decentralized employers such as charter and private schools. Consequently, they protect their desired market by opposing all school choice programs that enable students to attend schools not owned and managed by school districts.

The industrial model of unionism that teachers borrowed from the auto and steel workers 50 years ago assumes a large number of employees working in a centralized, command-and-control management system. Unions lose money when they apply this industrial unionism to smaller, decentralized employers such as charter and private schools. Consequently, they protect their desired market by opposing all school choice programs that enable students to attend schools not owned and managed by school districts.

But they are losing this fight. Parents like school choice. More than 40 percent of Florida students – 1.3 million - are now attending a choice school, and their numbers are increasing daily. As teachers move with their students and membership losses accelerate, teacher unions will eventually be forced to expand their business model to include services for teachers working for smaller, non-district employers. This expansion might include providing charter, virtual and private school teachers with liability insurance, financial planning, professional development, political advocacy and employee leasing for teachers willing to pay unions for guaranteed employment.

Teacher unions are an important vehicle through which teachers can make their voices heard and impact political decision making, but they have historically been conservative and resistant to change. The National Education Association, the nation’s largest teacher organization, resisted collective bargaining for several years and only relented after losing thousands of members to the AFL-CIO affiliated American Federation of Teachers. Both the NEA and AFT will refuse to embrace a more progressive, inclusive unionism until their membership losses are so severe they have no other choice.

This day is coming. When it arrives, teachers, unions, students and the public will all benefit.

Coming Friday: Two posts. Wishing school choice parents were impossible to ignore. And wishing for more information to help parents make the best choice.