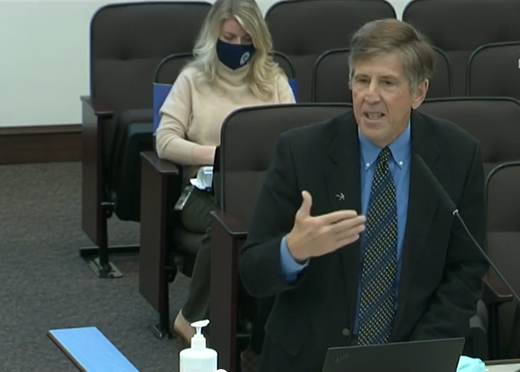

Editor’s note: This commentary from Step Up For Students president Doug Tuthill is a transcript of a podcast the reimaginED team recorded earlier this month. You can listen to the podcast here.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Step Up For Students president Doug Tuthill is a transcript of a podcast the reimaginED team recorded earlier this month. You can listen to the podcast here.

Q: Let’s start with your thesis. What main points do you think are important about teacher unions?

Tuthill: Unions have a symbiotic relationship with the industries within which they operate. A union’s business model is a function of how its industry is organized. The business model of a trade union representing carpenters and plumbers will reflect how the construction business is organized. A union representing home health care workers will reflect how the home health care industry is organized. And a union representing district schoolteachers will reflect how school districts are organized.

When the way an industry conducts business changes, the union’s business model must also change. Unions representing taxi drivers and retail mall workers are changing as ride-sharing services expand and much of retail shopping moves online.

Public education is in the early stages of a transition that is as impactful as how ride-sharing and online retail are transforming their respective industries. Public education is becoming more decentralized and public education services are increasingly being delivered outside of school districts.

One-size-fits-all education services are being replaced by customized services. Control of public education funds is transitioning from school districts to families. Teacher unions need to start transforming their business model to adjust to these industry-wide changes.

Q: What is your history with teacher unions and the labor movement?

Tuthill: I grew up in a blue-collar union household. Dad was a member of the firefighters’ union and Mom was a United Auto Workers member. Mom went on strike a few times and I was in middle school during the 1968 statewide teacher strike in Florida.

I became a union organizer in the spring of 1978 when I was elected president of the Graduate Student Union in Florida. We were affiliated with the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) and the AFL-CIO. We were also part of the United Faculty of Florida (UFF), which is the statewide faculty union representing college and university professors. I served on the UFF executive committee and was active in the AFT and the AFL-CIO.

In 1981, the AFL-CIO president asked me to serve on the organizing committee for the Solidarity Day march in Washington, D.C. That work lasted several months, involved hundreds of AFL-CIO unions, and about 500,000 marchers.

In 1984, I started teaching high school in St. Petersburg and became an active leader in our teachers’ union, the Pinellas Classroom Teachers Association (PCTA). I was PCTA vice president from 1988-91 and president from 1991-95. I also served on the board of directors of the statewide teachers’ union and did a lot of work nationally, and some work internationally, for the National Education Association (NEA), which is the country’s largest teachers union.

In 1995, I was a founding member of AFT/NEA sponsored Teacher Union Reform Network (TURN). I worked with TURN through 2001. From 2001 to 2003 I ran a union-sponsored organization that trained teachers and teacher union leaders.

Q: You toured the country in the early 1990s promoting a concept called new unionism. What was new unionism?

Tuthill: New unionism proposed a new mission for teacher unions. Instead of unions using their collective power to protect teachers from dysfunctional management systems, new unionisms advocated using this power to improve those systems.

The good people leading and working in school districts are well intentioned. But school districts still use a late-1800s industrial model of centralized, command and control management, which may be good for manufacturing Model T Fords but is an ineffective and inefficient way to manage public education. As a union organizer, I sold teachers protection from the many threats they faced working in these old industrial management systems.

Selling protection only works if people feel threatened, which is why teacher unions work to preserve these 19th century management systems while simultaneously selling teachers protection from those systems. Ironically, teachers are paying unions to perpetuate a system that threatens them, and for protection against these threats. The current teacher union business model is a protection racket. New unionism sought to change that.

Q: Why did teacher unions reject new unionism?

Tuthill: My friend Bob Chase was on the NEA Executive Committee. We spent several years discussing new unionism and Bob decided to make it a centerpiece of his 1996 campaign for NEA president. Bob got elected, but new unionism died early in his first term.

Protecting teachers from bad management is a very profitable business model. But more importantly, public education has been organized like an industrial assembly line since the 1800s. That model is deeply ingrained in local, state, and national policies, practices, and norms, and fiercely resistant to change.

Teacher unions will not improve until the larger public education ecosystem improves. Teacher unions are a subset of that ecosystem, and their business model derives from it.

Q: You assert that education choice is a necessary condition for improving public education and teacher unionism. Elaborate on this argument.

Tuthill: Public education is an overregulated, poorly performing market. The quality of our markets largely determines our standard of living. Imagine if the government owned all the housing in the United States and told people where they had to live.

Imagine if the government owned all the grocery stores and assigned people to grocery stores by ZIP code and assigned them the food they had to eat each day. In these scenarios the housing and food markets would function badly. There would be little innovation in housing or nutrition and people would rebel.

No one would tolerate the government dictating their housing and daily nutrition, and yet that’s how public education operates. We assign children to government-owned schools. We tell them what curriculum they will consume each day. And we now have about 150 years of evidence showing that doesn’t work for most students.

Despite all the evidence demonstrating that poorly functioning markets are bad, we continue insisting that public education be a poorly performing market. Giving families control over their child’s public education dollars is a necessary step toward creating a more effective and efficient public education market, which is why I support education choice. Education choice is a necessary condition for improving the public education market.

Education Savings Accounts (ESAs) contribute to a higher-performing public education market because they give families control over their child’s public education funds and provide them with the flexibility to purchase education services and products customized to each student’s needs.

As more families use ESAs, educators will have more opportunities to innovate and create more diverse education options they will own and manage. These changes will create new business opportunities for teacher unions.

Unions could help teachers create and manage their own education businesses, including micro-schools, virtual schools, home-school cooperatives, tutoring services, afterschool, weekend and summer programs, and traditional brick-and-mortar private and charter schools.

Teacher unions could help teachers access financing for physical infrastructure needs and provide administrative services such as bookkeeping, professional development, accounting/payroll, human resources, IT support, purchasing cooperatives, and employee leasing. (Some teachers may want to be employed by their union and contract with schools or other education providers on a part-time or full-time basis.)

Most teachers today must work in school districts because that’s where the jobs are. Freeing them to work for themselves or other teachers will allow them to have the professional status they have long been denied.

If lawyers can have lawyer offices, doctors can have doctor offices, and accountants can have accounting offices, why can’t teachers have similar professional opportunities? Why can’t teachers own public education businesses, and why can’t their union help them create and maintain these businesses?

For the foreseeable future, most teachers will continue working in district-owned schools. For these teachers, unions can continue offering their traditional protection, advocacy, and financial services, including legal protection, insurance, political advocacy, credit cards, and bargaining for salary, benefits, and working conditions.

Teacher unions do have opportunities to innovate within their current blue-collar union model. For example, professional sports unions integrate employee empowerment into their collective bargaining by negotiating minimum salaries and creating a well-regulated market within which individual employees may receive salaries well beyond the minimums. Many district teachers today would embrace the opportunity to be paid their true market value.

Q: Why won’t this version of new unionism fail like the last version?

Tuthill: In the early 1990s the public education ecosystem was not transforming like it is today. Currently, over half of Florida’s PreK-12 students are not attending their assigned district school. As more families assume greater control of their child’s public education dollars, teachers will increasingly leave school districts to take advantage of the opportunities created by this decentralization of public education spending. This expanding number of students being educated by teachers outside of school districts will eventually force teacher unions to begin selling services to these non-district employed teachers.

The pressures that led the NEA to become an industrial union provide a roadmap for how this next chapter of teacher unionism may unfold. The NEA was founded in 1857 and for over 100 years considered itself a professional association and not an industrial labor union. The AFT was founded in 1916 as a labor union for teachers. The first teacher union labor contract was ratified in 1962.

This contract launched the modern teacher union movement. Teachers in urban areas across the country began organizing themselves into labor unions and bargaining union contracts. AFT started to grow rapidly, and as NEA market share losses accelerated the pressure to turn the NEA into a labor union grew. By the mid-1970s the NEA had transitioned from a professional association to an industrial labor union.

As today’s teacher unions increasingly lose market share to organizations providing services to teachers working outside of school districts, they will start selling services to these non-district teachers in an effort to protect and recoup their market share. The NEA transition occurred over a period of about 20 years. I suspect a 20-year transition will also be needed this time. What I don’t know is when this transition will begin.

Q: Are you still a believer in teacher unions?

Tuthill: Teacher unions are comprised of good people working in bad systems. With the appropriate business model, teacher unions would be an asset in our efforts to create a more effective and efficient public education market.

According to the Wall Street Journal, the Securities and Exchange Commission is examining the for-profit business practices of Florida’s teacher unions and their for-profit business partners.

According to the Wall Street Journal, the Securities and Exchange Commission is examining the for-profit business practices of Florida’s teacher unions and their for-profit business partners.

The Journal reported recently that teacher union leaders are pushing teachers to purchase retirement investments from union-owned, for-profit companies that charge unusually high management fees. These higher fees are increasing the unions’ profits at the expense of teachers’ retirement funds.

The Journal writes: “The setup is one of an array of similar deals in which unions and other groups get income from endorsements of investment products and services — often at the expense of teachers … The ties help explain why many local-government workers continue to pay relatively high retirement-plan costs, while fees in corporate-based retirement plans are often lower and have been falling for years.”

I was first informed about the for-profit business ventures of teacher unions when I became a local union president in 1978. I had questions, but I was 22, and my mentors assured me our profits benefited our members and the union. Forty years later I still use a credit card that is managed by a for-profit joint venture involving the National Education Association (NEA), MasterCard, and Bank of America, even though I haven’t been an NEA member since 1997.

Given how critical teacher unions often are of for-profit businesses operating in public education, it’s ironic that these same unions operate a variety of for-profit businesses themselves. But the unions are selective in their criticisms. They only criticize for-profit businesses they perceive as competition, such as the small number of for-profit charter schools that aren’t unionized. For-profit contractors, bus companies, furniture vendors, teacher training providers and hardware and software companies, among others, are fine.

I do not object to teacher unions, or anyone else, operating for-profit businesses in public education. Without profit there would be no credit. Without credit there would be no scalable innovation. And without scalable innovation, we’d all be living in caves.

I also don’t object to teacher unions using their influence with the Democratic Party and the media to maximize their profits, provided it’s done legally and with transparency. All multimillion-dollar corporations, including teacher unions, work the media and lobby government to enact policies that advantage their businesses. I do object to teacher unions promoting their business interests in ways that hurt our most vulnerable and disadvantaged children. While the SEC is investigating the legality of the unions’ business practices, my concern is with the morality of their business practices.

In Florida, teacher unions have used their profits to help fund lobbying and lawsuits to take away education options from our state’s highest-poverty, lowest-performing students. Their goal is to protect their market share and revenue even though these actions hurt disadvantaged children and are inconsistent with the values of most teachers. Instead of attacking our most vulnerable children, teacher unions need a new business model that allows them to find common ground with these children and their families.

The future of public education is customization. Soon every child will have access to a customized education. Teacher unions need a business model that aligns with and supports customization. They will go out of business if they continue insisting that public education can only take place in government-managed schools covered by one-size-fits-all collective bargaining agreements. This 1970s model of public education, and the early 1900s model of industrial unionism that accompanies it, doesn’t work for many children and is going away.

There is a positive role for teacher unions in public education if they will adopt a new unionism that puts people above profits and empowers teachers and families to have more control over how each child is educated.

The Miami-Dade school districts ranks No. 10 among school districts nationwide in providing a wide array of school choice options for its students, according to a national report released today.

The Miami-Dade school districts ranks No. 10 among school districts nationwide in providing a wide array of school choice options for its students, according to a national report released today.

The Brookings Institution used its "Education Choice and Competition Index" to score more than 100 districts nationwide, using a complicated formula based on 13 categories. Among other factors, it looked at whether alternatives were available, including magnet schools, charter schools, virtual courses, vouchers, tax credit scholarships and affordable private schools.

The Recovery School District in New Orleans came in at No. 1, and earned the report's only A grade. (Miami-Dade got a B-.) New York City, Washington D.C., Minneapolis and Houston rounded out the Top 5.

A number of Florida school districts rated relatively high, including Hillsborough and Pinellas (tied at No. 19) and Broward and Duval (tied at No. 22).

The No. 10 ranking for Miami-Dade, which just won the Broad Prize for student progress, shouldn't be a surprise in Florida. As we've noted before, the district offers a substantial number of options on its own, through magnets and career academies, and, among the state's biggest districts, has some of the highest rates of students attending charter schools and private schools via tax credit scholarships.

It also has a superintendent, Alberto Carvalho, who said this a few months ago: "We are now working in an educational environment that is driven by choice. I believe that is a good thing. We need to actually be engaged in that choice movement. So if you do not ride that wave, you will succumb to it."

Unlike Kelly Garcia, fresh out of college I knew a lot about unions.

I grew up in a union household. My mom worked on a factory assembly line and was a member of the United Auto Workers. My dad was a fireman and a member of the International Association of Firefighters.

I started teaching in the fall of 1977, and by the spring of 1978, I was president of our local teachers union and a member of our state union’s board of directors. I moved to Pinellas County, Fla. in 1984 and joined their teachers union, where I was elected vice president in 1988 and president in 1991.

As my term was winding down in 1994, I thought about what I had experienced and learned over the previous 16 years and became convinced we needed a new model of teacher unionism.

Unions are always a reflection of the larger industries in which they reside. A union of freelance software engineers functions differently than a union of Ford autoworkers, or a union of independent truckers. Since today’s public education system took form during the industrial revolution, in the mid-to-late 1800s, today’s teachers unions operate much like the blue-collar unions that were spawned in those early factories.

New organizational structures were developed during the industrial revolution to efficiently manage the increased productivity generated by new machinery, and a rapidly growing public education system soon adopted many of these new structures and management systems. By the late 1800s, public schools increasingly began to resemble factory assembly lines with centralized, command-and-control management systems to generate greater efficiency and productivity through standardization. By the early 1900s, most public school students were moving along educational assembly lines in batches with teachers adding the prescribed knowledge and skills at each grade level.

Since children are not widgets, this production system was ineffective - and at times harmful - for many students. But as bad as these early school systems were for students, they were worse for teachers. They were controlled by politicians who were often more interested in accumulating and using power than educating students, and teachers were often the victims of their political manipulations. Increasingly, teachers rebelled against this unchecked political power, and began to fight back by organizing unions.

Adopting a union model similar to that used by the steel and auto workers made sense for teachers, given schools were organized like factory assembly lines. Teachers embraced centralized collective bargaining to respond to centralized management, and started bargaining for one-size-fits-all rules to counter the one-size-fits-all management practices.

By 1994, I understood the strengths and weaknesses of our blue-collar unionism. While we had blocked management’s ability to abuse their power, we had not empowered teachers and addressed their core desire to be more effective with students. We had turned school districts into unmanageable bureaucracies in which teachers and students were increasingly frustrated and alienated. And, under the guise of protecting public education, we had become the primary defenders of these bureaucracies. In essence, we had become an extension of management. (more…)

Former teacher union staffer and current Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa made news last week when he slammed the L.A. teachers union for being the "one unwavering roadblock to reform" in Los Angeles. According to the Los Angeles Times, Villaraigosa’s former union colleagues were furious at his “betrayal,” calling him a “turncoat.” But in the words of Harry Truman: “I never gave them hell. I just tell the truth and they think it’s hell.” Villaraigosa is correct. Teacher unions today are too conservative.

In the early 1960s, urban school districts were industrial factories controlled by political machines that were often more interested in maintaining political power than properly educating children. In response, teachers adopted a 1930s industrial model of unionism and began fierce political struggles for the right to collective bargaining. I joined those efforts in 1978 when I was elected president of a local Florida teachers union. I was proud when we finally won the right to bargain collectively in 1980 and I’m still proud of the improvements we achieved through organizing, bargaining and political action. But times have changed and unfortunately my former union colleagues aren’t keeping up.

Industrial-age unionism is no longer appropriate for a public education system that is abandoning the one-size-fits-all assembly line in favor of customized learning options. Teachers need a new unionism that uses collective power to promote individual teacher empowerment and embraces the innovations this empowerment will generate. (more…)