Oklahoma lawmakers created the most robust K-12 personal use tax credit in American history last year. It occurred to your humble author that with a couple of tweaks an Oklahoma-style credit could be productively included in the school choice mix of any state to turbo charge the choice mix, so I authored a study about it, including the following bit:

Oklahoma lawmakers created the most robust K-12 personal use tax credit in American history last year. It occurred to your humble author that with a couple of tweaks an Oklahoma-style credit could be productively included in the school choice mix of any state to turbo charge the choice mix, so I authored a study about it, including the following bit:

In 2023, Oklahoma lawmakers passed the most robust personal use education tax credit to date. The Oklahoma Parental Choice Tax Credit provides families sending their children to accredited private schools credits worth between $5,000 and $7,500 (varying by family income with lower-income families receiving larger credits). The law also provides for $1,000 for homeschooling students. Lawmakers designed the credit to be refundable. For example, a family with $5,000 of eligible expenses at an accredited private school but $4,000 in Oklahoma tax liability will still receive a $5,000 credit, with the difference reimbursed to the taxpayer.

Qualifying expenses for the private school credit include tuition and fees, whereas the law covers a broader array of educational expenses under the smaller homeschooling credit. For 2024, the Oklahoma lawmakers capped the private school tax credit program at $150 million, increasing to $200 million in 2025 and then to $250 million in 2026 and beyond.

Assuming a midpoint average between the $5,000 maximum for higher earners and the $7,500 maximum for lower-income families, ($6,250) the private school credit would serve approximately 40,000 students and the homeschool credit as many as another 5,000 students when it reaches the $250 million cap. This represents approximately 6% of the public-school enrollment of Oklahoma in 2022.

At the time of this writing of the study, approximately 160 Oklahoma private schools had registered with the state to participate in the private school credit. Family access depends on the number of participating schools, their proximity to families, and the number of available seats at the grade levels sought by families.

Oklahoma covers 68,577 square miles in land area, so 160 participating private schools is only one for every 480 square miles in the state. The state’s population of course is not distributed evenly throughout the state, but for context: Oklahoma has more than 1,700 public schools. The relative scarcity of private schools in the state makes the onboarding of new private schools crucial to the success of the program. Educators could create new private schools, especially in areas in which demand exceeds supply. Unfortunately, lawmakers did not design the Oklahoma Parental Choice Tax Credit Act in a fashion that recognizes the need for additional private schools.

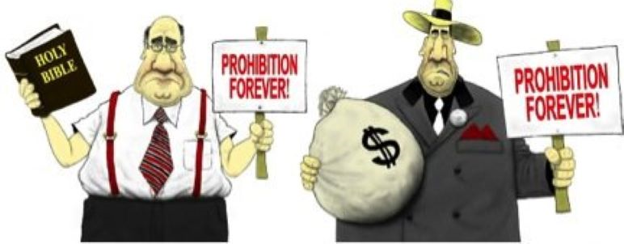

Step one to improve the Oklahoma Parental Choice Tax Credit: overcome our old nemesis, the Baptist and the Bootlegger coalition. In this instance, it appears that pre-existing accredited private schools in Oklahoma crushed potential competitors by denying them credit access. This could be accomplished by either dropping the accreditation process entirely, or else by allowing private schools seeking accreditation (often a multi-year process) to participate in the program. Assuming Oklahoma lawmakers want rural Oklahomans to participate, special attention should be paid to allow microschools to participate.

Given that public school attendance, private school attendance and homeschooling all satisfy the mandatory attendance requirement of Oklahoma, it is hard to see how private school attendance is 7.5 times more worthy of subsidy than homeschooling. Thus, an expanded list of allowable expenses for items such as tutoring, college tuition, books and other expenses helpful to a la carte education should be pursued. Again, Oklahoma’s bootlegger-accredited private school community will likely object, but the object of our policies should not be to create a parallel monopoly of private schools to subsist on a tame choice policy.

Next there is the funding amount. On the surface, $250 million seems to represent a large amount of money, put into context, it is not sufficient to drive dynamic K–12 change. The goal should be to have a demand-driven education system where teachers can create schools and recruit students who will be reliably funded. This is hardly too much to ask; district and charter schools receive funding in exactly this fashion. Programs funded by appropriation or with caps, however, create waitlists of students, introducing uncertainty in the process of creating new supply.

If Oklahoma parents hit the tax-credit cap in the third year of the program, the credit would educate more students than Oklahoma’s highest-funded school district (Oklahoma City) but would only provide a funding amount equal to approximately 56% of the Oklahoma City district’s budget. It’s a start on the journey, but not the desired destination.

The boldest move would be to eliminate the cap entirely and let ‘er rip. That would be as glorious as the melodious voices thousands of cherubim singing in exultation by my way of thinking. People elected to budgetary positions, burdened as they are by responsibilities and spreadsheets and such, might desire a more incremental approach. (Humbug, grumbles and wacky sassafras) Fortunately, Florida lawmakers provided us with a more incremental approach back in 2013:

In the 2013–2014 state fiscal year and each state fiscal year thereafter, the tax credit cap amount is the tax credit cap amount in the prior state fiscal year. However, in any state fiscal year when the annual tax credit amount for the prior state fiscal year is equal to or greater than 90 percent of the tax credit cap amount applicable to that state fiscal year, the tax credit cap amount shall increase by 25 percent. The Department of Education and Department of Revenue shall publish on their websites information identifying the tax credit cap amount when it is increased pursuant to this subparagraph.

Your mission, should you choose to accept it, is to take a great law and make it awesome. Remember to take competition to heart, then you can start to make it better.

Eleven states currently offer tax credits to specified taxpayers who make contributions to tax-exempt non-profit organizations that in turn use those contributions to fund scholarships for qualifying, financially-needy, elementary and/or secondary school students attending private schools. This fairly recent development is currently empowering perhaps 150,000 lower-income families, who generally are unable to afford private schools, to make this sort of school choice for their children. To be clear, these plans provide benefits for taxpayers who make contributions that help other people’s children attend private schools.

Sen. Marco Rubio, R-Fla., has just introduced a bill that would expand this tax credit scholarship initiative nationwide. To understand the good (and dubious) features of Senator Rubio’s proposal, it is important to appreciate the state law background against which it is set.

Florida has the financially largest of these 11 state tax credit programs, with about 50,000 children currently participating. It restricts the scholarships to children from truly low-income households; the child must be eligible for a free- or reduced-price school lunch – currently just over $40,000 a year for a family of four. Other states are more generous, with Oklahoma reaching well into the middle class since there a family of four can still qualify with $120,000 in annual income. Senator Rubio’s plan, while not as tightly restricted as Florida’s, focuses the scholarships on families with income no more than 250 percent of the poverty level, which is a bit over $50,000 today. The main thing to emphasize here is the senator clearly seeks by his bill to empower the least well-off Americans who are currently least able to exercise school choice – a choice that more well-to-do families make by either moving to a better public school district or paying for private schools on their own.

Several state plans give tax credits to both individual and corporate donors (and for corporate donors the plans sometimes allow credits against a variety of state taxes). Senator Rubio’s bill does the same – allowing married couples and single taxpayers both to obtain a federal income tax credit for an annual contribution of up to $4,500, and allowing corporations an annual corporate income tax credit of up to $100,000. Florida by contrast only allows corporate tax credits and Arizona (which was the first state to adopt this program) initially granted only individual tax credits. Senator Rubio’s proposed tax credit limit for couples and individuals is about twice that now allowed in Arizona. Some states have no cap on donations, and indeed in Florida a few very large corporate donors contribute millions each year to the plan.

Senator Rubio’s proposed tax credit is a 100 percent credit, as is true in both Florida and Arizona, for example. This means that for every qualifying dollar contributed, federal income taxes would be reduced by a dollar. This essentially makes contributions costless to the donors. They, in effect, are able to re-direct their tax dollars to this specific cause – helping needy families send their children to private schools. It is worth nothing, however, that some states grant only a partial tax credit, such as the 65 percent credit allowed in Iowa and the 50 percent credit allowed in Indiana. In those latter states, donors must put up some of their own money.

Most states that adopted these plans imposed a maximum overall limit on the amount of tax credits that may be claimed each year in support of the program. These maxima vary enormously and even so are often not reached. Senator Rubio’s plan has no such limit. It probably would be complicated and costly, but clearly not impossible, for the IRS to administer an overall ceiling in a way that allowed would-be donors to know whether their contribution was within the national maximum and hence truly eligible for the credit.

One important difference between many state plans and Senator Rubio’s proposal is there is no limit on the amount of the scholarship that may be awarded. Florida, for example, caps scholarships at $4,335 at present; in Georgia the limit is just over $9,000. Hence, as appears to be the case in states like Iowa and Indiana, it would be legally possible under the senator’s plan for a child to win a full scholarship to a very high cost, elite private school and hence indirectly obtain government financial aid well beyond what is now being spent on public schools. This is perhaps unwise. Note, however, that nothing in Senator Rubio’s bill would require scholarship granting organizations to award full scholarships or high-value scholarships. In many states at present, the average scholarship is less than $2,000 a year. Since it would be rare to find a school with tuition that low, either the families must find some way to come up with the difference, or the schools must use their own financial aid plans to make up some or all of the gap.

The most striking difference between most state plans and Senator Rubio’s is children already enrolled in private schools would be eligible for scholarships. (more…)