Melody Bolduc, (left, kneeling) with her students and staff. Bolduc founded KEYS Educational Resource Center to supplement homeschoolers' educational experience. Photo courtesy of Melody Bolduc

On this episode, reimaginED senior writer Lisa Buie talks with Melody Bolduc, a homeschooling mother of two daughters and founder of KEYS Educational Resource Center, a faith-based tutoring center for homeschoolers in Jacksonville, Florida.

Bolduc says how she wanted to be a teacher as early as first grade, when she and her friends would play school most afternoons. Bolduc felt drawn to teaching because she perceived teachers as having autonomy in their jobs. Bolduc went on to tutor classmates, including a girl she later realized had special needs that caused her to struggle with spelling. After working in district schools, Bolduc opened KEYS Educational Resource Center after becoming a mom so she could better fulfill family responsibilities. She started KEYS after a couple of friends asked her to tutor their homeschooled children.

“I would go over to (my friend’s) house once a week, and we would practice on a little chalkboard. We would practice, and practice and practice. I remember the first time she passed the spelling test, and I loved that I was able to teach her something.”

https://nextstepsblog.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Reimagined.bolduc_mixdown-final.mp3

EPISODE DETAILS:

RELEVANT LINKS

Bolduc’s presentation at the 2022 Liberation of Education Conference

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dRDNUNZRkyU&list=PLT5UPtq10X0xnK6yFs5FgRPDOh8-EM843&index=7

KEYS Educational Resource Center

https://www.keyserc.org/

Editor’s note: To read a comprehensive overview of Coons’ efforts to change the face of education choice, researched and reported by Step Up For Students’ director of policy and public affairs Ron Matus, click here.

Editor’s note: To read a comprehensive overview of Coons’ efforts to change the face of education choice, researched and reported by Step Up For Students’ director of policy and public affairs Ron Matus, click here.

On this special episode, recorded to coincide with the publication of renowned Berkeley law professor Coons’ new book, “School Choice and the Human Good,” he and Tuthill discuss Coons’ more than 50 years of education choice advocacy on behalf of the poor and working classes.

A self-styled liberal from California, Coons and fellow law professor Steven Sugarman crafted a plan in 1978 that would have created more educational options for the parents of 4.5 million California students. As one reporter observed at the time, the plan would have taken a wrecking ball to the old order, installing a new one overnight.

Here’s how a front-page headline in the Los Angeles Times described the plan:

The idea is called school vouchers … this particular form turned out to be too radical even for the 1960s, and it died aborning … Now, however, the voucher idea is alive again, but not just as a theory or a pilot experiment. A statewide initiative is being proposed to make California the first state to establish an entire system of voucher schools, including public, private nonsectarian and religious.

Coons and Tuthill discuss the remarkable twist of fate – the murder of education choice advocate Congressman Leo Ryan in the 1978 Jonestown Massacre – that changed everything. Coons also relates his experience with education icons such as Albert Shanker and Milton Friedman and his unshakable belief that giving less affluent families choice over their children’s education is important for society at large.

“We have got to get the language straightened out. (Education choice supporters) are the liberals. You are opening up democracy for the poor. So long as people yell and scream at you as fascists because you happen to be for choice, let them look in the mirror ...

“It is wrong to fight against (choice) on the grounds that it is a right-wing conspiracy. It's a conspiracy to help ordinary poor people to live their lives with respect.”

EPISODE DETAILS:

Tracy James, foreground, and her daughter, Khaliah Clanton-Williams, are greeted by principal Maria Mitkevicius and administrator Mary Gaudet at the Montessori School of Pensacola. Khaliah was one of the first students to use Florida's "first voucher," the Opportunity Scholarship, in Fall 1999. PHOTO: Michael Spooneybarger

Editor's note: 2019 marks the 20th anniversary of the far-reaching K-12 changes that Gov. Jeb Bush launched in Florida, including creation of the first, modern, statewide private school choice program in America. To highlight those changes, redefinED embarked upon a series of articles that examine Bush's "education revolution" and how it continues to reverberate. Today's piece spotlights a mom and daughter who participated in Florida's historic Opportunity Scholarship.

PENSACOLA, Fla. – Tracy James finished the graveyard shift to find her car a casualty of the “voucher wars” – and her 8-year-old, Khaliah, needing another ride to school.

This was 20 years ago, when this Deep South Navy town became the front in the national battle over school choice. In June 1999, Florida’s new governor, Jeb Bush, had signed into law the Opportunity Scholarship, the first, modern, statewide, K-12 private school voucher in America. Khaliah and 56 other students in Pensacola were the first recipients, and now enmeshed in a political clash drawing global attention.

CNN came. A Japanese film crew showed up. So did a member of British Parliament. All wanted to see the “experiment” a Canadian newspaper said “will shape the future of public education in this state and perhaps across the United States.” Tracy and Khaliah were in the thick of it, with Tracy among the most outspoken of an unconventional cast of characters. The single mom with the self-described rebel streak wouldn’t hide her joy at this opportunity for her only child – and refused to cave to anybody who suggested she was being “bamboozled.”

“If you want something better for your children,” she told one paper, “you would do the same thing.”

Not everybody appreciated her resolve.

Tracy walked out of her shift as a phlebotomist to find her car sabotaged, three tires flat as week-old Coke. She called her dad, who said he could take Khaliah to her new school, one Tracy could not afford without the scholarship. The flats left Tracy shocked and ticked – and more determined.

I guess I need tougher skin, she thought. Because we ain’t going back.

***

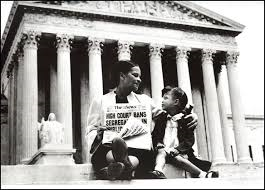

Lots of folks know Ruby Bridges. But Khaliah Clanton-Williams? Maybe one day.

The original Opportunity Scholarship students, their parents, and the five private schools that welcomed them have never gotten their due. After an epic legal battle, the Florida Supreme Court ruled the school choice program unconstitutional in 2006, and the decision in Bush v. Holmes seemed to close the chapter. But it didn’t. Many of those whose lives were touched by the scholarship have untold stories, with some still unfolding in ways that attest to the power of that experience.

In one sense, the Opportunity Scholarship was as small-scale as it was short-lived. Students were eligible if their zoned public schools earned two F grades in a 4-year span, and in 1999 only two schools – both in Pensacola – fell into that category. At the same time, most private schools sat it out. Among other restrictions, the law barred them from charging tuition beyond the scholarship amount of $3,400 to $3,800. At its height, the Opportunity Scholarship served 788 students.

And yet, it loomed so large. Florida’s “first voucher” stirred the imagination about what could be with a more pluralistic, parent-driven system of public education. It exposed the festering dissatisfaction many parents had with assigned schools. It enabled and amplified voices that still aren’t heard enough.

Pensacola may be best known for its Blue Angels and sugar-sand beaches. But most of the parents who applied for the school choice scholarships were working-class black women – nursing assistants and bank tellers, cooks and clerks, Head Start workers and homemakers. They had a lot to say about schools in Pensacola’s low-income neighborhoods, and for a few months in 1999, they had the mic.

***

Khaliah’s assigned school was modest red brick, five blocks from her home, named for the district’s first “supervisor of colored schools.” Khaliah would be starting kindergarten, so Tracy stopped to visit. She never got past the front office. “It was a zoo,” she said. “Kids were running around. They were screaming. There was no discipline. There was no structure.”

Nobody with the school acknowledged her, so after a few minutes, Tracy left … for good. She turned to her only option: another district school near her mother’s house, two miles away. Tracy said her mom, a former custodian for the school district, became Khaliah’s guardian so Khaliah could attend. But that school didn’t pan out either.

One day, Tracy watched through a window as kids in Khaliah’s class danced to music blaring from a boom box. She found the teacher in a side office and asked what was going on: “ ‘She said, ‘It’s reading time.’ I said, ‘They’re not reading.’ “ Tracy opened her eyes wide for emphasis.

Khaliah, meanwhile, shy and soft-spoken, was falling behind. “I had a hard time concentrating because it was so loud,” she said. “I’d ask for help and it was like, ‘just a moment.’ But the moment never came.”

Tracy heard about Opportunity Scholarships while working another job as a hotel desk supervisor. Some guests asked her in passing about local schools, and as fate would have it, they were lawyers with the Institute for Justice, the firm that would later help defend the scholarship in court.

Ninety-two students applied for the scholarships, including Khaliah, who had come back to live with Tracy. That exceeded the available seats in the four Catholic schools and one Montessori that opted to participate, so a lottery was held.

Khaliah emerged with a golden ticket.

***

Tracy took her time before deciding on a school. She read up on Catholic schools, talked to friends and co-workers who attended Catholic schools, learned everything she could about Montessori. She was intrigued by the latter – by the mixed-age classrooms, the cultivation of creativity, the curriculum that was so different. In the end, the rebel and her daughter decided they wanted different.

Khaliah Clanton-Williams, left, used an Opportunity Scholarship to attend the Montessori School of Pensacola from second through seventh grades. She and her mother, Tracy James, revisited the school last week for the first time in years. PHOTO: Michael Spooneybarger

Khaliah attended Montessori School of Pensacola from second through seventh grade, and, in Tracy’s words, “blossomed” in confidence and knowledge. She returned to public school in eighth grade (Tracy wanted her re-acclimated to public school before high school) and graduated from Pensacola High in 2010. For most of the next few years, she worked as a mortgage loan officer. She earned her associate degree in business administration from Pensacola State College in 2018. She’s on track to earn a bachelor’s in human resources management (with honors) in 2020.

Without the Montessori, Khaliah said, much of that would not have happened.

“It made me better,” she said. “I don’t think I would have gone to college. I don’t think I would have gotten my degree. (Montessori) made education more important. It was a higher standard.”

The upside wasn’t just academic. Tracy and Khaliah said nearly everyone in the school embraced Khaliah as family. There were only a few black students before a few more enrolled with the scholarships, but race was not a divide, they said. Khaliah made fast friends. They invited her to sleepovers, to ride horses, to U-pick blueberries. “These things were normal to them, but not to me,” she said.

Montessori co-owner (and head of elementary and middle school) Maria Mitkevicius said increasing diversity was a big reason the school opted into the scholarship program. So was the belief the school shouldn’t be limited to parents of means.

The staff knew the stakes, even if they didn’t know how much things might change. Twenty years after five private schools and 57 kids cracked the door, at least 26 private schools in Escambia County (Pensacola is the county seat) participate in Florida’s K-12 school choice scholarship programs, serving at least 2,163 students. Statewide, 2,000 private schools serve more than 140,000 scholarship students, with thousands more on the way.

“We thought this might change the face of education,” Mitkevicius said. “I guess it did.”

***

The news on Pensacola TV showed 10,000 sign-waving students and parents, marching at a 2016 school choice rally in Tallahassee with Martin Luther King III. As Khaliah watched it again last week, tears fell.

It hurt, she said, to see so many who still don’t have choice or fear their choices could be taken from them. At the same time, how nice to see strength in numbers.

“Back then,” she said, meaning 1999, “it was just us.”

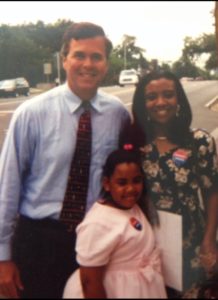

Tracy James and her daughter, Khaliah, with former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush circa 1999. Bush championed creation of the Opportunity Scholarship program, which allowed Khaliah to attend a private school. PHOTO: Courtesy of Tracy James

Remembering back then is tough for Tracy too. Some in Pensacola’s black community could not understand why black parents would support anything connected to Jeb Bush. “We were looked on as kind of those people who are being arm twisted by the governor, like you’re letting the Republicans bamboozle you,” said Tracy, now a clinical recruiter for a Pensacola hospital.

It got ugly. Dirty looks. Heated words. The tires. Tracy said some friends and family stopped speaking to her, and she switched jobs because she felt she was being harassed for taking a stand.

But the rebel has no regrets.

“I wanted to try something different, I wanted to be different, I wanted a different opportunity for my daughter,” Tracy said. “From what I saw happening, I wanted to be able to make the choice, myself, of where she’d end up as an adult.”

“I had no idea that it’d turn out to be such a controversial issue,” she continued. “To be thrown into sort of the limelight of a political battle, I had no idea. I had absolutely no idea how important it would be.”

Or how much of a struggle.

“When we went through that program, I was thinking that was kind of the end of an era,” Tracy said. “But it was actually the beginning.”

***

The shy girl who helped pioneer school choice is now a tough-minded mom who needs more.

Khaliah is married to a paper mill machine operator, and their oldest, Kyrian, will begin kindergarten this fall. His zoned school is one of 11 D-rated schools in the district, so like her mom before her, Khaliah looked for alternatives. She applied to three higher-performing district schools through an open enrollment program, but all were full. On a second go-round, Kyrian got into a new elementary north of Pensacola. It’s not ideal. The drive will be up to 45 minutes each way, and Khaliah switched jobs – to drive for Shipt, Lyft and Uber – so she can have flexibility.

Still, she’s worried. Kyrian has special needs – he’s hyperactive, averse to change in routine and undergoing speech therapy – but has not been formally diagnosed with anything. At this time, he wouldn’t qualify for any of Florida’s private school scholarships.

The irony isn’t lost on Tracy and Khaliah. School choice helped them. They helped pave the way for more. Yet 20 years later, there still isn’t enough choice for Kyrian.

The rebel’s daughter said that just means the work isn’t done.

“I’ll continue to fight for my children as my mom fought for me,” Khaliah said. “I’m not taking no as an option.”

The legal regime that emerged after Brown v. Board of Education did not correct the underlying imbalance of power.

Generations of black students fought to leave St. Louis public schools, but third-grader Edmond Lee wants to remain in his.

Under city rules designed to promote racial desegregation, however, he might be forced out of his school because he is black.

Edmond and his mother, LeShieka White, are moving to the suburbs, away from the public charter school he attends. While researching Edmond's enrollment options, White discovered a 33-year-old desegregation agreement prohibits black students living in the suburbs from enrolling in inner-city public schools, and non-black students from leaving.

White, a victim of unintended consequences, has since gotten a good bit of media attention, and started a petition to change the state law to allow her son to stay in his school. It now has more than 120,000 signatures.

James Shuls, an assistant professor at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, argues the race-based transfer restrictions in his city may already be unconstitutional. He points out a similar program in Arkansas was struck down in 2012 after the court ruled that race-based transfer requirements violated violated the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

The absurdity of Edmond's case – a child being denied access to a public school because of his race – underscores the difficulty of reconciling decades-old desegregation efforts with the proliferation of charters and other school choice options. Should the decades-old logic of desegregation still apply when the government no longer has the sole power to dictate where children go to school? (more…)

Gloria Romero

Gloria Romero Gloria Romero, a former Democratic majority leader of the California Senate, helped pass a bill that required parents to be informed if their child attended a school in the bottom 10 percent of all public schools in California. If they did, the parents could stick around at the school and try to transform it (for example, by converting it to a public charter school) or transfer to a different public school.

The teacher unions and school districts opposed the bill, sued to stop the program, and continue to fight the program to this very day.

According to Romero, the state department of education delayed releasing the list of lowest-performing schools until the last minute. With only a few weeks remaining before the transfer deadline, L.A. Unified finally posted the transfer application, but only in English and only online. Districts also denied parent groups from informing parents of their rights at school events such as PTA meetings.

Kudos to Romero and the California Center for Parent Empowerment for highlighting these obstacles and fighting with and on behalf of parents to knock them down.

Carmen Farina, the chancellor of New York City Public Schools, recently accused charter schools of pushing out low-performing students just before statewide exams.

Carmen Farina, the chancellor of New York City Public Schools, recently accused charter schools of pushing out low-performing students just before statewide exams.

Charter schools responded by demanding the chancellor back up her claims with evidence. And the local union president more or less sided with them, saying enrollment data for both charter and district schools should be audited and disclosed. Marcus Winters even took her to task for misreading what little data is available.

Perhaps with some irony, Farina made those remarks while clarifying her position on how charter schools need to be more transparent. Now she has the opportunity to be transparent about her claims.

"Polly" Williams

Happy Birthday! The Milwaukee Parental Choice Program, America’s longest-running private K-12 school voucher program, is now 25 years old.

The program has not gone without controversies and critics but researchers generally find, at worst, no difference with traditional public schools and, at best, small but positive achievement gains, graduation rates and college attendance for participating students. Importantly, parents and students are happier going to the school of their choice rather than one assigned to them by the government. On a sadder note, Annette "Polly" Williams, a leading black Democrat and school choice leader who pioneered the program recently passed away. Her legacy, however, lives on.

Edit Barry is a mother, activist, writer and education blogger from Baltimore who criticized my recent blog post connecting feminism with school choice, where I wrote:

The school choice movement is founded on the empowerment of teachers and custodial parents. Since most teachers and custodial parents are women and since feminism is about empowering women, the school choice movement is rooted, in part, in feminism.

In a comment to my post, Edit asked me to defend my position by more precisely defining feminism and giving examples of local feminists who support school choice.

Feminism is part of the movement to democratize power. Feminists seek to ensure women’s abilities to acquire and use social, economic and political power are not inhibited by their gender. Most feminist activism occurs in local communities.

Yvonne Clayton-Reed is an African-American woman who taught in the Pinellas County school district for 34 years. Twenty years ago, Yvonne retired on a Friday and on the following Monday used her retirement funds to open a private school in the basement of her church. Yvonne is passionate about teaching black children how to read, and she’s especially proud of her work with low-income black boys.

Yvonne is a legendary educator in our neighborhood and, despite health challenges, refuses to quit. In addition to her work in the classroom, she’s also a community organizer and political activist. Two years ago, when we held a rally in Tallahassee to support scholarships for high-poverty children, Yvonne filled two buses and led her families to the Capitol steps in her wheelchair.

Suzette Dean moved from the Islands to Florida as a teenager and ended up earning an education degree from the University of South Florida in Tampa. While at USF, Suzette began tutoring students and when she graduated she and her husband Daniel decided to open a church and school in one of Tampa’s highest poverty neighborhoods. They had few financial resources but managed to borrow enough money to purchase a small piece of land and with their own hands built a small church and school.

Today Suzette is raising five children while running a K-12 private school with about 100 students. She is also the chief administrator for the church, runs an afterschool tutoring program for the neighborhood public middle school and helps Daniel with a variety of community development projects.

Yvonne and Suzette are feminists who utilize school choice to improve their communities. Unfortunately many state and national feminist leaders want to deny these women and their communities the empowerment that comes from school choice. For example, the National Organization for Women’s website refers to school choice advocates as “right wingers” who “are intent on passing an array of voucher proposals and tax credit proposals that favor the well-to-do.” And in Pennsylvania the state NOW branch recently opposed a tax credit scholarship for low-income students to attend private schools.

I know most feminist leaders are Democrats and since Jimmy Carter changed the Democratic Party’s position on parental choice in 1976, most Democrats now oppose private school choice. But for community organizers like Suzette and Yvonne, parental empowerment is not about party politics or ideology. It’s about having the tools they need to empower and enable the low-income families in their communities.

I hope Ms. Barry will one day visit Tampa Bay and talk with Suzette, Yvonne and other local activists about how publicly-funded private school choice impacts their community development work. I’m sure she’ll find the dialogue interesting and these women inspiring.

The school choice movement is founded on the empowerment of teachers and custodial parents. Since most teachers and custodial parents are women and since feminism is about empowering women, the school choice movement is rooted, in part, in feminism.

Civil rights leaders, such as the legendary Florida civil rights leader H.K. Matthews, have for years argued that school choice is an essential component of the modern civil rights movement, but feminist leaders nationally haven’t made a similar connection. Women at the grassroots across the country are fighting for the power to create more diverse learning options for children and to match their children with the learning options that best meet their needs, but unfortunately national feminist leaders seem to be ignoring their struggles. Perhaps their silence is a reflection of race and class differences within the women’s movement. Much of Florida’s school choice movement is being led by low-income women of color.

Seeing these women advocate for their children is inspiring. They hold planning meetings in the evening after working two jobs, ride all night on buses to Tallahassee, march on the capitol, testify in committee meetings and then ride all night home so they don’t miss a second day of work.

These feminists know that finding the right educational fit for their children is a matter of life and death, and they will not be denied.

The school choice movement is one of the most dynamic and growing sectors of modern feminism. That this effort is being lead by local activists with little formal connection to feminist leaders nationally is a reaffirmation that the fuel for democracy and social justice always comes from below.

Most parents try to protect their child from dangers, to nourish their child's development, and to instill values and a sense of purpose in their child so that, as he or she matures, each child will be able to make sensible choices for his or her own life path.

Yet, most parents need government assistance in order to promote their children's best interests. For one thing, if left unchecked outside forces may overwhelm parental efforts. These include the child's peers, undesirable cultural and commercial influences, and so on. In addition, family poverty and ignorance may prevent parents from effectively carrying out their roles.

To be clear, parents need help, not only from extended family members and the community at large, but also from government. For example, public regulation can increase parental power and authority over their children by preventing others (like retail cigarette sellers) from tempting children into self-destructive behaviors. The state can also provide information (or require others to provide information, like movie ratings) that parents need to enable them to make good decisions for their children. Moreover, government can provide resources (like food stamps) that some parents lack. In all of these power-enhancing ways, government can help parents better fulfill their responsibilities to their children.

Sometimes, in the name of "child protection," government reduces rather than enhances parental power. To be sure, as a last resort it may be necessary to substitute collective or professional decisions as to what is best for children. Yet policymakers may be too quick to override parental control when further empowering parents would, overall, be best for children.

Other times, government actions are misleadingly framed as "child protection" measures that, on closer analysis, may be better understood as actually parent-empowering (like issuing teenage driving licenses that limit when youths may drive and who may be in the car with them).

Add to that this key point: it may often be politically easier to win the adoption of a policy when it is understood as helping people be good parents than when it is understood as curtailing parental authority. Isn't helping people be good parents something on which conservatives (the "family values" groups) and liberals (who talk of "personal empowerment") agree? By contrast, the constituency may be narrower for "child protection" measures, especially those that are seen to push a large share of parents around because "legislators or experts know better."

Take the problem of childhood obesity, for example. Getting colas out of middle school vending machines and junk food commercials off TV programs aimed at children ages eight and younger removes temptations that parents generally would like to be out of sight. Policies that would achieve those ends empower parents to have more control over what their children eat. This is not the nanny state. Parents who still want to feed their kids Froot Loops and have them drink Cokes are free to do that.

Finally, then, consider the debate over school vouchers (or scholarships) for children from households of modest means. They should not be defended on the ground that this mechanism will improve the test scores of America’s children or that it will destroy teachers’ unions and unleash the wondrous innovations of capitalism. Those are collective objectives that some people favor (and others oppose, doubt, or care little about). Rather, subsidized school choice is best promoted on the ground that it empowers additional families to make decisions for their children that nearly all parents want to be able to make. Just like food stamps, school scholarships for needy families can help parents be better parents.

In a Wall Street Journal column today on the controversy surrounding the NAACP joining the New York City teachers union in an anti-charter school lawsuit, William McGurn writes:

For those who understand that our big city public school systems have become jobs programs for teachers and administrators, the NAACP's response makes perfect sense. That's because there are many African-American teachers in these systems, many of whom presumably belong to the NAACP … The NAACP is doing in New York what the United Federation of Teachers is doing, and for the same reason: protecting the interests of its members.

In an entry on redefinED last fall I discussed why middle-class African Americans feel such loyalty toward school districts and why this loyalty is fraying in Florida. Thanks to a variety of parental empowerment programs in Florida, African-American educators and local community activists are increasingly opening up financially-viable schools, and as these publicly funded private schools provide more middle-class teaching jobs, the middle class African-American community -- which includes African-American politicians -- is embracing them.

If the NAACP and New York City teachers union were more enlightened, they would understand that a centralized, command-and-control public education system is not in the best interests of teachers, parents, students or taxpayers. A public education system that empowers educators and local communities to create their own schools and empowers parents to match their children with the schools that best meet their needs is the best path to equal educational opportunity. Unfortunately both the NAACP and New York City teachers union are on the wrong side of history.