Editor’s note: This commentary from former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush appeared earlier this week on RealClear Education.

Editor’s note: This commentary from former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush appeared earlier this week on RealClear Education.

The past two years have shined a bright light on widespread inequalities in education. As state after state dealt with pandemic disruptions, we’ve seen painful reminders of what’s always existed: some kids have access to great schools, multiple options for learning, and abundant resources like computers and high-speed internet access, advanced courses, online classes, and modern buildings with science labs and excellent libraries.

And other kids are left behind, decade after decade, assigned to government-run underperforming and failing schools, without a chance for anything better. That’s painfully true in Michigan, where a student’s ability to move to a better school is limited by antiquated state laws that don’t serve the needs of each and every individual student.

Consider Michigan’s failure in teaching students to read according to the “Nation’s Report Card.” For a dozen years, Michigan’s 4th grade reading scores have been below the national average, and, in 2019, six out of 10 Michigan 4th graders were not proficient in reading. These scores touch all parts of Michigan, including the urban centers of Detroit, Flint, and Grand Rapids, and rural communities throughout the state. Math scores are below the national average, and there’s a growing achievement gap between white and Black students.

But why?

If we’ve learned one thing from the pandemic, it’s that our education system must be flexible and centered around students. A single, one-size-fits-all pathway for every kid will never deliver great results. A quality education that meets a child’s needs unlocks countless doors. It can break cycles of poverty, lift up communities, and help ensure all students can reach their God-given potential.

To read more, click here.

![]()

A parent’s story: How a Florida education choice scholarship may have saved my daughter’s life

A parent’s story: How a Florida education choice scholarship may have saved my daughter’s life

Rayonna faced some challenges in school with somebody that was once her friend. This girl started to bully my daughter because she did not want Rayonna to talk to a girl she didn’t like. My daughter was uncomfortable in this situation, and I started getting calls from her while I was at work. She explained the situation to me, and she kept telling me, “Mommy, I don’t want to get into a fight, but this person keeps coming at me. I know I’m going to end up fighting her.” My daughter was never someone who concerned herself with violence, but now she was telling me this. READ MORE

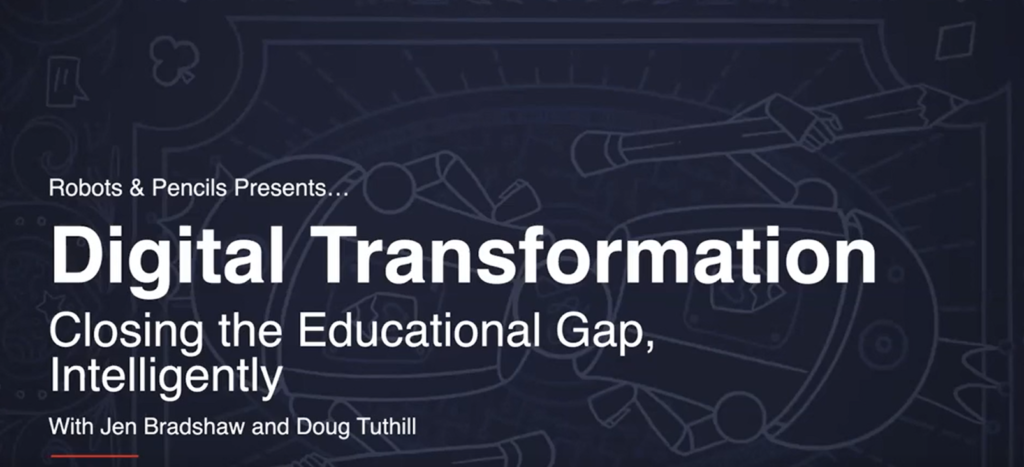

podcastED: SUFS president Doug Tuthill and NLP Logix client delivery manager Jen Bradshaw discuss future of education savings accounts (Part 1)

podcastED: SUFS president Doug Tuthill and NLP Logix client delivery manager Jen Bradshaw discuss future of education savings accounts (Part 1)

On this two-part episode hosted by Kevin Roberts of the digital innovation firm Robots and Pencils, Tuthill and Bradshaw discuss a partnership between Step Up For Students and Jacksonville-based artificial intelligence company NLP Logix, which aims to create a simple and customizable online platform for families who use education savings accounts to support their children’s education. Tools such as artificial intelligence-based predictive analysis must be deployed to bring education savings accounts to scale in public education and to help families READ MORE

Communities should use pandemic recovery funds inside, outside traditional school to benefit K-12 kids, families

Communities should use pandemic recovery funds inside, outside traditional school to benefit K-12 kids, families

COVID-19 school shock disrupted our way of doing education, unbundling the familiar division of responsibilities among home, school and community organizations. Nearly every parent of school-age children had to create from scratch a home learning environment using online technology, rebundling school services to meet their needs. Most parents accepted whatever teaching, learning and support services their district offered, supporting their child’s learning as best they could. Other parents sought new learning options. READ MORE

Results from a new poll from RealClear Opinion Research indicates that voters have a problem with lawmakers who oppose school choice for others but exercise it for their own children.

Results from a new poll from RealClear Opinion Research indicates that voters have a problem with lawmakers who oppose school choice for others but exercise it for their own children.

According to a survey conducted this month of more than 2,000 registered voters, 62% would be less likely to vote for a candidate who opposes education choice policies yet sends his or her own children to a private school. The sentiment was evenly shared by those who identified as Democrat, Republican and Independent.

Researchers asked the question: If an elected official or political candidate sends their own children to private school but opposes school choice for other families, would that make you more likely to vote for that candidate, less likely to vote for that candidate, or would it not make a difference?

Here is the breakdown among political affiliation:

Democrats were 56% less likely to vote for such a candidate; Republicans were 66% less likely; and Independents were 65% less likely.

American Federation for Children CEO Tommy Schultz said in response to the poll results that it’s unfortunate that politicians block expanded educational opportunities for others while exercising that freedom for their own children.

“From president of the United States governors to state lawmakers and school board members, many in such places of privilege disregard the needs of families who want nothing but the same opportunity to access an educational environment that meets their own children’s needs,” Schultz said.

Editor’s note: reimaginED welcomes its newest guest blogger, Garion Frankel, with this post on a viable education choice alternative for rural families.

Editor’s note: reimaginED welcomes its newest guest blogger, Garion Frankel, with this post on a viable education choice alternative for rural families.

The past two years have seen an unprecedented string of victories for parental choice advocates. After the events of the COVID-19 pandemic, more than two dozen states now offer some form of voucher program.

But amid this expansion of school choice, the concerns of rural Americans are often overshadowed. Millions of American students attend a rural school, and many families interpret vouchers of any kind as a threat to their way of life. This resentment often influences policy.

For example, the Texas House of Representatives, based on the support of rural Republicans, added an amendment banning the use of vouchers to the state budget, which will be in effect until 2023.

"The reality is we have plenty of options and choice within our public schools,” said state Rep. Dan Huberty, a Republican who has long opposed voucher-driven school choice.

Rural concerns are valid. Anyone who has ever seen an episode of Friday Night Lights knows what the local public schools can mean to a rural community. Rural schools can employ half a town, and the other half will pack the bleachers for a high school football game.

These are institutions that can’t simply be overlooked. Furthermore, it’s true, at least historically, that rural access to voucher programs has been poor.

But there is now an option that can adequately serve both a single mother from Baltimore and a family with deep roots in rural Wyoming. Education savings accounts can satisfy the needs of all Americans, and arguably strengthen rural schools in the process.

Like traditional vouchers, ESAs enable parents to withdraw from their traditional public school and receive a deposit of public funds into a state-authorized savings account. Families can usually access this account via a debit card, and the money may be used for limited, but varied uses, such as private school tuition and supplemental instruction.

The difference, however, comes in the breadth of ESAs. They are not really vouchers. Instead of being specifically directed towards private schools, ESAs allow families to effectively design an educational program from scratch. In some cases, as with West Virginia’s Hope Scholarship Program, some students can use ESAs to support their public education.

In addition, ESAs can actually increase public school per-student spending. When families elect to participate in an ESA program, they receive only the state-allotted portion of their education. Sure, the public school district wouldn’t receive that portion of their funding, but it would be able to keep the locally sourced revenue that would normally have gone toward serving that student. As such, school districts can increase their per-student spending when ESAs are available.

For rural school districts, this extra spending would be particularly important. Before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, rural schools struggled to provide adequate internet services as well as the technology to access them. ESAs could open the door for higher-quality internet or laptops for students to use during class.

On the other hand, those rural families who do want something different would be able to pursue other options without feeling like they are destroying a pillar of their community. Nobody should feel guilty for doing what they think is best for their child’s future, and with ESAs, that choice could ever enhance their community.

There is no time like the present to implement school choice measures, and with ESAs, rural communities could comfortably join the broad, nationwide coalition of parental choice advocates.

There are no more excuses for blocking school choice efforts. Standing against ESAs is neither conservative nor acting in the interest of preserving communities; it is merely selfish and narrow-minded.

Rural communities arguably are the heart and soul of American culture and identity. That should apply to school choice too.

Education choice advocate Howard Fuller poses with a student at Milwaukee Collegiate Academy during a visit to the school in 2019. The school, which he co-founded in 2004, has been renamed Dr. Howard Fuller Collegiate Academy.

Editor’s note: This article about education choice pioneer Howard Fuller from Jon Hale, associate professor of education at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, appeared Monday on The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization that encourages Creative Commons republication.

As a longtime civil rights activist and education reformer, Howard Fuller has seen his support for school choice spark both controversy and confusion. That’s because it aligns him with polarizing Republican figures that include Donald Trump and Trump’s former secretary of education, Betsy DeVos.

But unlike those figures, Fuller’s support for school choice is not rooted in a conservative agenda to privatize public schools. Rather, it is grounded in his ongoing quest to provide Black students a quality education by any means necessary.

I write about Fuller in my new book “The Choice We Face,” which traces the history of school choice as well as demands for radical education reform by Black activists. Unlike most other school choice advocates I interviewed, Fuller’s activism predates the current debate and has firm footing in the Black Power movement.

Now 80, Fuller retired in June 2020 from Marquette University, where he was a longtime education professor and founded the Institute for the Transformation of Learning to improve education options for low-income students in Milwaukee. During the 1990s he served as superintendent of Milwaukee Public Schools.

Here are five aspects from Fuller’s career that suggest a nuanced lens into the school choice movement.

Advocated for Black Power in the 1960s

Fuller first became involved in the civil rights movement when he joined the Congress of Racial Equality in 1964 as a graduate student at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio.

In Cleveland, Malcolm X delivered a version of the “Ballot or the Bullet” speech in April 1964. Days later, Rev. Bruce Klunder, a 27-year-old white Presbyterian minister, was accidentally crushed to death by a bulldozer as he and several other activists protested the construction of a new, all-Black school. The school was the city’s attempt to avoid desegregation.

Fuller later helped establish and lead Malcolm X Liberation University in Raleigh, North Carolina. The independent, Black-run school, which operated from 1969 to 1973, offered a unique African and African American studies curriculum as well as technical training for students to work as activists in the freedom struggle.

Controlling and safeguarding a school for one’s own community became a defining principle of the Black Power movement. For Fuller and others, education was liberation for Black communities. As Fuller described it, the mission of the university was to educate students “totally committed to the liberation of all African people.”

Proposed an all-Black school district in the 1980s

In 1978, Fuller was embroiled in a struggle in Milwaukee to save his alma mater, North Division High School, from closing. That year, Derrick Bell, who is regarded as the “godfather” of critical race theory, delivered an address in Milwaukee titled “Desegregation: A New Form of Discrimination.”

In his speech, Bell criticized education reforms that were more concerned with balancing racial demographics in schools than with improving Black education. He argued that building programs that did not always accept local Black students but made space for white students who lived outside the neighborhood hurt Black students. Much like Fuller’s North Division High School, Black students were not guaranteed admission to the school closest to their home if those schools were designed to attract white students.

Several years later, Howard Fuller drafted the “Manifesto for New Directions in the Education of Black Children.” The treatise proposed carving out an all-Black school district within the Milwaukee public school district to serve over 6,000 students. The district was to be controlled by and geared toward families of color. The plan was a response to a call made in 1935 by W.E.B. DuBois, who argued that Black educators and activists should invest more in building Black schools than integrating hostile white schools.

Supports school vouchers today

Fuller’s proposal for an all-Black school district gained traction, but Wisconsin legislators opted instead for a voucher plan in 1989 – the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program. The program covered the tuition of students who wanted to enroll in private schools.

The Republican Party seized on the new voucher plan and pushed it through the state legislature. Ever since the Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954, when the Supreme Court declared school segregation unconstitutional, the Republican Party has increasingly aligned itself with school privatization efforts through vouchers and “freedom of choice” plans.

Fuller also supported the Milwaukee voucher plan, as did some other Black activists, despite criticism from academics and organizations, including the NAACP.

“If you’re drowning and a hand is extended to you, you don’t ask if the hand is attached to a Democrat or a Republican,” noted Wisconsin State Rep. Annette “Polly” Williams, a Black Democrat who worked with Fuller to propose the legislation for a separate school district and also supported school vouchers.

Helped build the school choice movement

Howard Fuller helped build the foundation for civil rights activists who are interested in school choice. As he told me during our interview in 2019, “I’ve always seen school choice from a social justice framework as opposed to a free market framework.”

Many activists saw it the same way.

For example, Wyatt Tee Walker, one of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s trusted strategists, opened a charter school in New York City in 1999. James Forman Jr., a civil rights lawyer, scholar, author and son of the prominent Black Panther Party organizer, opened a charter school in Washington, D.C. in 1997. Both leaders argued that failed desegregation attempts placed a burden on Black families by catering to white families without promising quality education for Black students.

Meanwhile, education activist Geoffrey Canada was awarded the National Freedom Award in 2013 for his charter school network, the Harlem Children’s Zone. And in 2016, Martin Luther King III led one of the largest school choice rallies in the nation. “This is about freedom,” King told the crowd gathered in Florida, “the freedom to choose for your family and your child.”

Support for choice is not limited to a small cadre of activists. A 2019 poll by the American Federation for Children estimated that 73% of Latinos and 67% of African Americans support school choice.

Drew scorn for working with Republicans

Fuller allied with prominent Republicans on school choice. He met with George W. Bush in 1999 while Bush was running for president. A year earlier, he debated then-Sen. Barack Obama on the issue of vouchers. His school reform work in New Orleans in the 2000s led him to collaborate with Betsy DeVos, who at that time was a GOP financier and charter school advocate. He also later supported DeVos’ contested nomination for secretary of education.

Fuller drew strong criticism from the press and some education reformers for his connections with the GOP, who earned a tarnished reputation on civil rights, and for embracing what many defined as a conservative agenda.

In his own defense, he noted in our interview that while he agrees with some Republicans on school choice, he strongly disagrees with them “on voter ID, on drug testing for people getting public assistance. I support the minimum wage. I support Obamacare.”

Though his position on school choice did not curry favors with progressive education reformers, Fuller demonstrated that not all demands for school choice are the same. For instance, he believes “mom and pop” charter schools are more emblematic of the long history of the Black freedom struggle than schools proposed by national charter school networks, as these grassroots schools are more often driven by the demands of historically marginalized communities.

“You’re going to be fighting for something for entirely different reasons than some of the people out there who are your allies,” Fuller said in our interview.

I believe this difference is imperative to understanding the nuance of school choice today.

On this two-part episode hosted by Kevin Roberts of the digital innovation firm Robots and Pencils, Tuthill and Bradshaw discuss a partnership between Step Up For Students and Jacksonville-based artificial intelligence company NLP Logix, which aims to create a simple and customizable online platform for families who use education savings accounts to support their children’s education.

On this two-part episode hosted by Kevin Roberts of the digital innovation firm Robots and Pencils, Tuthill and Bradshaw discuss a partnership between Step Up For Students and Jacksonville-based artificial intelligence company NLP Logix, which aims to create a simple and customizable online platform for families who use education savings accounts to support their children’s education.

Tools such as artificial intelligence-based predictive analysis must be deployed to bring education savings accounts to scale in public education and to help families successfully navigate the complex decisions they need to make for their children’s unique educational needs. Tuthill, Bradshaw and Roberts discuss the new platform and the factory-model history of public education that quickly is becoming obsolete as well as how using data to inform families and help them access resources is a natural integration of humanities of science that meets pressing needs in education.

“Think about a single mother with a 10th-grade education who's busting her fanny to do the very best for her child. We've got to do everything we can to help that mother succeed for her kids."

EPISODE DETAILS:

The fluid nature of the pandemic catalyzed a “new” solution – supplemental learning pods – with approximately 12% of parents enrolling their children in learning pods as a supplement to their core school.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Bruno Manno, senior adviser to the Walton Family Foundation’s K-12 Program and reimaginED guest blogger, appeared Monday on The 74.

COVID-19 school shock disrupted our way of doing education, unbundling the familiar division of responsibilities among home, school and community organizations.

Nearly every parent of school-age children had to create from scratch a home learning environment using online technology, rebundling school services to meet their needs. Most parents accepted whatever teaching, learning and support services their district offered, supporting their child’s learning as best they could.

Other parents sought new learning options.

A study from Tyton Partners calculates that during the 2020-21 school year, 15% of parents changed their child’s school, a rate 50% higher than pre-pandemic levels. Overall, 2.6 million students exited district and private schools, enrolling in charter schools, homeschooling, microschools and other options. Thirteen percent of families also enrolled their child in small learning pods, supplementing traditional school.

In doing so, these parents exercised their agency to work with like-minded community members, many of whom were outside the current K-12 system — call them civic entrepreneurs — to create new organizations or expand existing ones to meet this demand.

There is now an unprecedented amount of K-12 federal dollars — around $190 billion and counting from three new pandemic-related programs — for people and programs to remedy the huge academic, social and emotional toll that COVID-19 imposed on young people and their families, with 90% ($171 million) going to school districts. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that local districts may not exhaust stimulus dollars until 2028.

To continue reading, click here.

The Master’s Academy in Oviedo, Florida, is a Christian School that opened to 230 students in 1968. It now serves more than 1,000 students enrolled in K2 through 12th grade, and provided a lifeline for Debra Manning’s daughter, Rayonna.

Editor’s note: This first-person essay from Florida mother Debra Manning debuted on the American Federation for Children’s Voices for Choice website.

Debra Manning, left, and her daughter, Rayonna

Rayonna faced some challenges in school with somebody that was once her friend.

This girl started to bully my daughter because she did not want Rayonna to talk to a girl she didn’t like. My daughter was uncomfortable in this situation, and I started getting calls from her while I was at work. She explained the situation to me, and she kept telling me, “Mommy, I don’t want to get into a fight, but this person keeps coming at me. I know I’m going to end up fighting her.”

My daughter was never someone who concerned herself with violence, but now she was telling me this. I was really concerned, but I worked on the other side of town, and I knew I wouldn’t be able to get to Rayonna in time. So, I called my mother, and she went to pick my daughter up from school. When she got there and discussed this with the administrators, they just kind of brushed her off. I told her I would deal with it the next day.

That night, my daughter came into my room, and she told me to look at her phone. The young lady that was bullying her had sent her a text that pictured both fists and gun emojis with the words, “I am going to get you.” I took that very seriously and I went to the school the next day to discuss the situation.

The school really didn’t do much to solve this situation. They told the resource officer and called the girl and her mom up to the office, but their only solution was to make the girl stay home from school for the remainder of the year, which was about a month. That was not good enough for me. The girl could be sent home, but there was nothing stopping her from leaving the house and going to the school of her own volition.

As a parent, I knew that I would be constantly paranoid if I left my daughter in school while I was at work. Instead of leaving her at school, I told the school that I was going to bring her in every morning for her attendance and schoolwork, but that I would be taking her home after to do it. They didn’t really want me to do that, so I called the regional office and let them know the situation. They approved of it and for the remainder of the school year that is what we did.

This was only a temporary solution, and I knew that I had to find my daughter a new school before the new school year began.

I started looking for schools, and a friend of mine told me about Master’s Academy. I went to tour the school and from the moment I stepped into the school, I felt so much better. Everything was just so much better, from the way they greeted me to the smaller class sizes. The school asked me if I had ever heard of Step Up for Students and to apply for financial assistance through them. I honestly did not know if I would get it, but I tried.

When we got the notification that we had been approved, I was so happy. My daughter felt so comfortable at Master’s Academy, and I was at ease.

Being able to send your child to a school that where you feel comfortable that they are getting what they need is a must. I am a product of public schools and I have nothing against them. However, they are crowded with almost 30 students in one classroom. Kids cannot learn like that. It is also hard to notice bullying when you have to pay attention to so many kids. On top of that, my daughter was just so much more comfortable. She no longer had to worry about bullying and the smile on her face at that school was so worth it.

I think that every parent should have the ability to choose the right school for their child. Every child learns at different paces and in different ways. In a smaller classroom setting, teachers are able to accommodate every child. No one child is sacrificed because the teacher cannot spare the extra time for them. On top of that, there is a more comfortable environment between the parents and the school.

If my daughter is struggling, I know the school will work with me on what she needs. I am not saying a public school will not do that, because sometimes they do. What I am saying that it is more plausible in a smaller school environment. Every child and parent should be able to expect that from their school, but unfortunately, they cannot. That is why having the ability to choose your school matters so much.

Without the Family Empowerment Scholarship, I’m not sure where my daughter would have ended up. I could not have kept her in her zoned school with a threat to her life. But, as a single mom, I could not have paid for private school out of pocket.

I have a good and stable career, but I live paycheck to paycheck. I am already worrying about how to keep a roof over our heads and clothes on my child’s back. I should not have to also worry about paying for her to receive a safe and quality education, but I did.

Our representatives have the ability to send their kids to private schools if their zoned schools are not good enough, because they have the money to do so. Why shouldn’t I get that option when my daughter’s zoned school was failing her?

Editor’s note: Juliette Harrell and her husband, Allen, found themselves in one of the worst situations a family could face: homeless, with children, and no resources for how to get back on their feet. Then the Orlando, Florida, couple found out about the Family Empowerment Scholarship Economic Options program for families on limited incomes.

Editor’s note: Juliette Harrell and her husband, Allen, found themselves in one of the worst situations a family could face: homeless, with children, and no resources for how to get back on their feet. Then the Orlando, Florida, couple found out about the Family Empowerment Scholarship Economic Options program for families on limited incomes.

They were able to place two of their children – 10-year-old Aiden and 6-year-old Amar’e – in a private school near their home. With the boys’ education needs addressed, Juliette and Allen were able to focus on working toward financial stability. reimaginED senior writer Lisa Buie recently recorded a podcast with Juliette Harrell about the family’s ordeal and their hope for a better future.

Here are excerpts from the podcast.

We got to a point where the cost of living was going up … At one point, we couldn’t afford to live on just one income. Then I lost my job. We had to figure things out. How were we going to manage? We thought we had enough savings … we ended up being homeless. During that time of homelessness, me and the children were living in a coalition and (my husband) decided it would be best to move in with his mom. That was a really challenging time for us. We felt defeated.

Then one day, my husband spoke with a woman who told us about (the state scholarship) … he said it’s based on your income. I said, ‘Well, we don’t have very much income.’ I did the application and applied for the scholarship, and we were approved.

Being able to have a school that’s so resourceful was vey helpful. We were able to save up money. They offered in the community classes in financial literacy. I was able to attend those classes. With that help, I was able to become more financially aware. We were able to find housing based on our income … We were able to purchase our first home.

The school the boys go to is in walking distance … Aiden is exceling, and the teachers are amazing. They’re challenging him because he’s very bright. With Amar’e … he’s adjusting well. We’re making sure he gets the resources he needs.

We are encouraged and thankful for the Family Empowerment Scholarship. It has really made a difference. I don’t know where we would be without that resource.

To hear the full podcast, click here.

Editor’s note: This article appeared Friday on The Center Square.

Editor’s note: This article appeared Friday on The Center Square.

The Mackinac Center Legal Foundation partnered with Bursch Law to file a lawsuit alleging Michigan’s restriction on the use of public funds to pay for private education is unconstitutional.

Five Michigan families and the Parent Advocates for Choice in Education (PACE) Foundation, a nonprofit supporting the rights of Michigan parents to provide educational opportunities for their children, joined the lawsuit after conventional public schools frustrated them after the COVID-19 pandemic. Plaintiff Jessie Bagos’s school only provided virtual school for her young children for much of the last school year. She wanted other options for her twin boys starting kindergarten instead of sitting in front of a screen.

“To have the option to choose schools would be life changing,” Bagos said in a statement. “For everyone, not just us. Hopefully this lawsuit can help with that.”

Section 529 of the Internal Revenue Code allows state-sponsored savings plans to fund higher education expenses. Michigan’s plan is Michigan’s Education Savings Plan (MESP). Bagos funded an MESP and wants to spend that money on their children’s private, religious school tuition.

But Michigan’s Blaine Amendment, passed in 1970, prohibits using public funds for private education. If Bagos spends MESP money on private, religious education, the Blaine Amendment will reverse Michigan’s tax deduction the parents received upon contribution.

To continue reading, click here.