Updated Feb. 10, 2026

Record breaking interest continues with more than 300,000 students who have applied for Florida’s K-12 education choice scholarships for the 2026-27 school year.

Step Up For Students, the nonprofit organization that administers 98% of the state’s scholarships, opened applications for the 2026-27 school year on Feb. 1. A record 200,000 applied during the first three days.

By mid-day Feb. 10, a total of 300,106 students had applied for scholarships, which represents an 11.7% increase over the same 10-day period last year.

Step Up For Students CEO Gretchen Schoenhaar said last week that the organization’s team and systems were ready for the surge of interest. Step Up’s technology systems processed 15% more applications on the first day this year than at the same time last year. Of the families who called for assistance, more than 90% reported being “satisfied” or “very satisfied” with the support they received.

“Another record number of applications on our opening weekend shows that Florida families increasingly value options in their children’s education,” Schoenhaar said. “Step Up For Students smoothly processed the higher demand and is prepared to support families every step of the way.”

During the 25-26 school year, more than 525,000 students have been funded on Florida’s K-12 scholarship programs to access learning options of their choice. If these students were counted as a single school district, it would be the largest in the state and third largest in the country. That makes Florida the national leader in education options.

However, not all students whose families apply end up being awarded or funded.

Step Up is focused on supporting growth. By the end of the year, Step Up expects to process 3 million reimbursements and a total of 3 million MyScholarShop e-commerce transactions.

Current scholarship families have until April 30 to renew their scholarships for the next school year. All families who want a PEP scholarship must also apply by April 30.

Private School and Unique Abilities Scholarship applications will be available through Nov. 15 for families who want a new scholarship.

Applications and more details are available here.

We will continue to update the numbers in this post until applications close.

VENICE – He is not afraid.

Lyra Kerr wants to make that clear.

He is not afraid to climb a ladder that rises 29 feet above ground. He’s not afraid to stand on the small platform near the top of that ladder and reach for the bar that will swing him over the safety net.

Lyra is not afraid to hook his knees on the bar and dangle as he swings.

And he’s certainly not afraid to release his grip and spin once, twice, three times before bouncing to a stop in the net.

Yes, Lyra wears a harness and is assisted by two trained trapeze artists, but he’s 6, and the climb and the swinging and the spinning could be unnerving for a beginner, let alone one his age.

But, said his mom, McKenna Rodgers, “He’s fearless.”

“It’s not scary,” Lyra said. “It’s super fun.”

In fact, he added, it’s “the most super fun” thing he does.

For 90 minutes two days a week, Lyra is the daring young man on the flying trapeze.

He trains under world-renowned trapeze artist Tito Gaona at Gaona’s trapeze academy in Venice. The fee is reimbursed through his Florida education choice scholarship, managed by Step Up For Students.

Lyra, his stepsister and stepbrother each receive the Personalized Education Program (PEP) scholarship available through the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship Program. PEP provides parents with flexibility in how they spend their scholarship funds.

The scholarship enables McKenna to home-educate all three, who are enrolled in Florida Virtual School. She said her stepchildren, both teenagers, have improved scholastically since receiving the scholarship, especially in reading.

Lyra is just beginning his academic journey. McKenna is curious about where it will lead him and how, with PEP, she can tailor his academic needs and interests.

“I’m really happy to have access to it,” she said.

Lyra makes it look easy. (Video courtesy of McKenna Rodgers.)

The scholarship has paid for extracurricular activities for all three, including circus camp in the summer. Lyra is the only one who returned for training classes.

Tito Gaona said that Lyra can go as far as he wants to in the sport.

“Trapeze is a lot of fun, addicting. Once you get on a piece and you really like it, there's no end, because you fall in love with it because it's fun,” he said.

Venice, known as the “Shark's Tooth Capital of the World” for the tiny finds buried in the sand along its beaches, was once known as the “Winter Home of the Greatest Show on Earth.”

From 1960 to 1992, Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus brought circus performers, workers, and animals to Venice during the offseason.

McKenna, born and raised in Venice, has fond childhood memories of seeing the performers train during the winter, especially the trapeze artists.

Tito Gaona’s Trapeze Academy is located near the municipal airport. When McKenna drove by with Lyra, she would point at the students swinging through the air and tell him she always wanted to do that when she was his age.

One day, Lyra said he wanted to be a trapeze artist, and McKenna decided she was going to make it happen.

“It wasn't a vicarious thing,” she said. “It was just something we had around here that is not common and is unique to the area. The circus had its winter headquarters here, and should keep it alive in a way. Performance art is important.”

And Lyra did have some practice flying. Sort of. They lived for a time on a houseboat, and Lyra often dived into the water.

“I jumped off the boat,” he said. “Off the roof, really.”

Looking for ways to harness Lyra’s energy, McKenna had already enrolled him in gymnastic classes. Tumbling through the air was a logical next step for a boy who loves to climb trees and dangle from bars in the playground near their Venice home.

Among the many perks of home education is that parents can set the daily schedule. This allows McKenna to keep some mornings free to take Lyra to the beach.

“No one’s there,” she said. “It’s my favorite time.”

Like a typical 6-year-old with boundless energy, Lyra’s interests are all over the place. He loves to swim, fish, play video games, and play with LEGOs. Right now, he is constructing “The Lord of the Rings: Barad-dûr,” the dark tower found in Middle-earth.

He even tried his hand at racquetball.

Nothing, though, beats the thrill of learning the trapeze.

The climbing, dangling, dropping, spinning.

To Lyra, none of it is scary.

It’s the most super fun.

TALLAHASSEE, Fla. — Luz Acosta-Pandolphi was happy to be among the crowd gathered in the state Capitol courtyard Thursday afternoon to celebrate National School Choice Week. For her family, education choice is multigenerational.

Her daughter went to an Avant School of Excellence, which serves students in elementary, middle and high school at locations in Tallahassee and Florida City near Miami. Now, her two grandsons attend the school.

“It is a school where they fit in perfectly,” she said. One grandson has dyslexia and now can read at grade level, thanks to Avant, she said. State K-12 school choice scholarships make it affordable to send both boys.

“We wanted to be here to support choice,” Acosta-Pandolphi said.

She wasn’t alone. About 1,000 students showed up with their parents and school leaders to celebrate Florida’s many learning options and the fact that the Sunshine State is a national leader in education choice.

They sang the national anthem. They listened to a group of students at a classical charter school recite Ralph Waldo Emerson’s 1837 poem “Concord Hymn,” which includes themes of sacrifice and freedom. They danced.

Several state lawmakers joined the celebration. As bills were being debated inside, it was all harmony in the paved courtyard. Only smiles, red and yellow balloons, and a celebration of the right of families to choose the best education for their children.

“How meaningful it is to stand here with you today, surrounded by families and students and teachers and education leaders whose lives are shaped every day by the power of the right educational fit,” said state Rep. Jennifer Canady, R-Lakeland. “Here in Florida, we are doing something truly special.”

Canady, a former teacher who holds a master's degree in special education, is the chairperson of the House Education & Employment Committee and was elected to be Florida’s first female House speaker in 2027.

Other state representatives who spoke included Reps. Michelle Salzman, R-Pensacola; Alex Rizo, R-Hialeah; and Yvette Benarroch, R-Marco Island.

School leaders stood up and praised state leaders for realizing that when it comes to education, one size does not fit all, and for empowering parents to direct their children’s education.

The celebration was co-sponsored by Americans for Prosperity Foundation and the National School Choice Awareness Foundation, both 501c3 organizations. Shenell Ellerbe, said choice had made a difference for her daughter, Subi, who attends the Digital Academy of Florida, a virtual school that Ellerbe said best fits Subi’s unique needs.

“It also provides flexibility, which is good because we travel,” Ellerbe said. She said Subi, who is in high school, is thriving and wants to attend college and study botany. She said having the ability to choose the best fit for Subi has made a significant difference for her academically.

“We felt it was important to come out here and show our support for choice,” Ellerbe said. The season open for scholarship applications for the 2026-27 school year is Feb. 1. Visit Step Up For Students to apply.

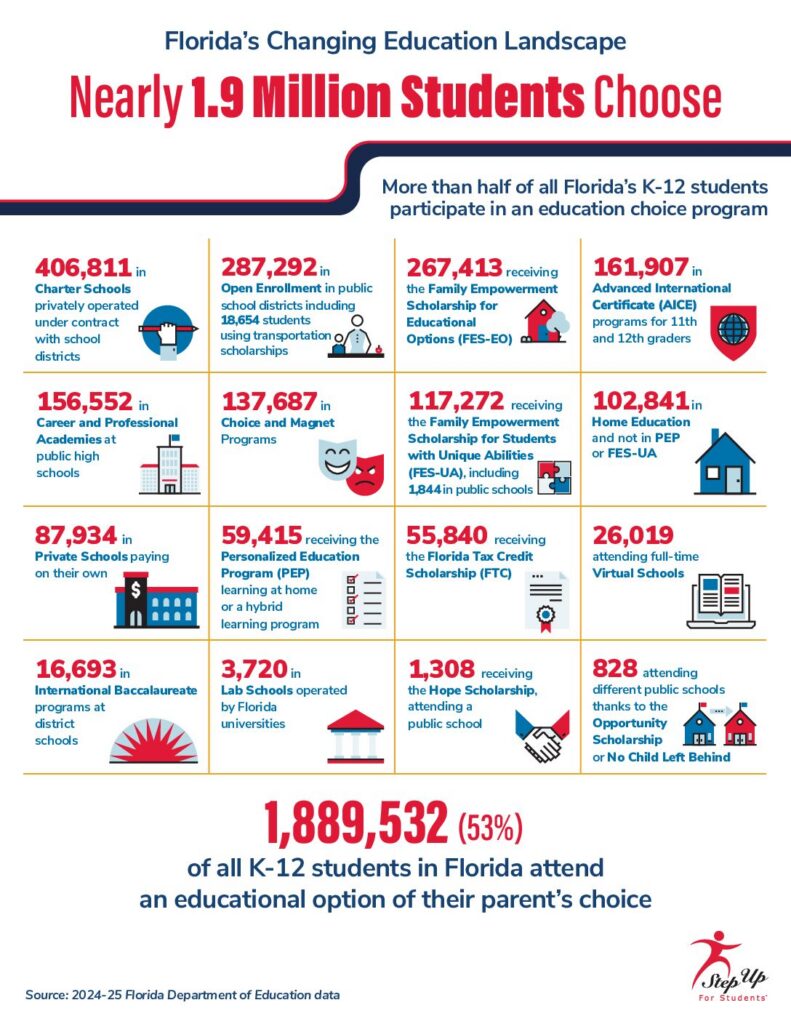

Florida’s K–12 education landscape continues to shift toward choice. During the 2024–25 school year, 53% of all K–12 students — 1,889,532 children — attended a public, private, or home education option of their parents’ or guardians’ choice. Just one year after crossing the 50% threshold for the first time, Florida’s school choice participation grew by nearly 100,000 additional students.

“Each year, Florida families have made it clear that they want more options for their children’s education,” said Gretchen Schoenhaar, CEO of Step Up For Students, the Florida non-profit that administers the state’s education choice scholarship programs.

“Increasingly, parents and guardians are willing to mix and match private and public resources to choose the ones that work best for their family.”

Since the 2008–09 school year, Step Up For Students, in collaboration with the Florida Department of Education, has tracked enrollment across a variety of choice programs. The 2023–24 school year represented a historic milestone: the first time more than half of all K–12 students in the state attended a school of choice. The 2024–25 school year continued that upward trend.

The Changing Landscapes report draws from Florida Department of Education data and removes, where possible, duplicate counts to provide a clearer picture of school choice participation. For example, it adjusts for home education students supported by the Family Empowerment Scholarship for Students with Unique Abilities (FES-UA) and eliminates double-counted students in career and professional programs. It also excludes prekindergarten students in FES-UA and programs such as Voluntary Pre-Kindergarten (VPK), as the report focuses solely on K–12 education.

While many families still choose their neighborhood public schools, Florida’s education system now offers a broad range of options to meet diverse student needs. As in past years, public school choice remains dominant, occupying four of the top five spots in overall enrollment. Charter schools are the most popular single option, followed by district open enrollment programs, the Family Empowerment Scholarship for Educational Options (FES-EO), career and professional academies, and Advanced International Certificate of Education (AICE) programs for upperclassmen.

The largest increases in enrollment occurred in the FES-EO program, which has merged with the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship program, and the Personalized Education Program (PEP), a scholarship that helps fund education at home.

Among public school options, AICE enrollment grew nearly 17%, career and professional academies grew 6.2%, and open enrollment grew 4.6%. While overall district enrollment appeared to decline slightly, these public school choice options still grew more than charter schools (independent public schools), which grew just 2.3%. This may suggest that school districts could benefit from expanding their own menu of diverse school options to better retain families.

Choice remains strong within Florida’s public school system. More than 1.2 million of the state’s 2.9 million public school students attended a school of choice, while another 688,000 students outside the public system enrolled in private schools or home education programs.

A newer option to keep an eye on is district schools offering classes and services to students on an education choice scholarship, paid for with their scholarship funds. Currently 37 of Florida’s 67 districts have been approved as providers with Step Up For Students, and another 11 are in the process of being approved. These arrangements further blur the line between public and private and emphasize that the focus remains on the individual needs of students.

With so many options available, Florida’s education system has entered a new phase. Choice is no longer an alternative; it is the norm. Families routinely evaluate multiple pathways, and whether they select a different option or remain in their assigned public school, they are making an active choice. The result is an education landscape in which public, private, and home education options coexist and evolve together, reflecting the reality that students and families have different needs, and that those differences matter.

The spring trip to Sweden and Finland for a hockey tournament would be a scholastic problem for Nick Hacking if not for a Florida education choice scholarship.

The games will be played over 10 days in April. Add travel to and from that part of Europe, and that’s a lot of time away from school.

“If he were in a (traditional) school and missed that much time in April, I can’t even imagine that,” said Nick’s mom, Corrie.

But Nick, 12, is home-educated and receives a Personalized Education Program (PEP) scholarship available through the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship Program.

Not only does the scholarship allow his parents the flexibility to customize Nick’s learning to meet his interests and needs, but because Nick learns at home, he has flexibility in his school day.

So do the more than 76,000 Florida students using the PEP scholarship program managed by Step Up For Students. Families seeking PEP and other school choice scholarships for the 2026-27 school year can apply starting on Feb. 1.

“The PEP scholarship is amazing,” Corrie said. “I cannot recommend it enough. From what I’ve seen with other parents, more and more families are looking into it as an option. You have control over your child’s education and curriculum, and you have control over the scheduling.”

So, when Corrie learned her son was selected for the Tampa Bay all-star team that would compete in a two-week tournament overseas, she took the planner that lists Nick’s spring curriculum, grabbed a pen, and made some adjustments.

“I said, ‘Okay, we still need to get these lessons done. How do we get these lessons done?’” Corrie said.

Easy. You squeeze in a little more time in March for math and science, and maybe double up on language arts.

“And when we get to April,” Corrie said, “we’re still ahead.”

Nick can even pack some schoolwork along with his ice skates, hockey stick, and equipment, and study while in Stockholm or Helsinki, two of the tournament sites.

“It gives us that flexibility,” Corrie said.

Corrie made similar adjustments last year when Nick traveled to Detroit for a hockey tournament.

The Hackings live in Palm Harbor, not far from the Tampa Bay Skating Academy in Oldsmar, where Nick practices with his Tampa Bay Hockey Club team. Nick has been playing hockey for six years, making the move from youth football after an ice-skating outing with his friends.

“He just put the skates on his feet and took off,” Corrie said.

He is a defenseman, partly because he’s not afraid of contact with opposing players and partly because he can blast the puck on net with long-range slap shots. He is among the top scorers on his team.

Not surprisingly, Nick’s weeks are filled with hockey. There are near-daily practices, Thursday morning training sessions, and Thursday afternoon skate-and-shoot sessions.

Nick spends almost his entire Thursday at the Tampa Bay Skating Academy. This also worked into his school schedule. He does the bulk of his schoolwork on Mondays, Tuesdays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. There is some time set aside on Thursday mornings for a quick lesson or review; otherwise, the day is reserved for hockey.

Nick said he loves the flexibility of learning at home, where the school day normally begins at 9 a.m. and ends in the early afternoon. Plus, his teacher (his mom) allows for a little rec time if she feels Nick needs some exercise.

Sometimes he'll take the dogs for a walk. Sometimes he’ll retreat to the family’s garage and begin shooting pucks at the walls.

“There are dents,” Corrie said with a measure of pride found among hockey moms.

Scott, a telemedicine family physician who works from home, and Corrie, a stay-at-home mom, began homeschooling Nick and his sister, Natalie, during the 2023-24 school year. (Natalie has since returned to her district school.)

Prior to that, Nick and Natalie attended a hybrid private school, which they attended three days a week with the other two spent at home.

“After doing the two days a week at home, I thought, “I can do this. I can do all of this," Corrie said. “I love it because I don't have to worry about someone I don't know teaching my kids.”

And she likes how she can tailor the curriculum. Nick is interested in math and science, where his average is in the high-90s in both. He spent two years learning Latin because he found the ancient language interesting, though he recently switched to Italian.

Natalie is a competitive cheerleader. Scott and Corrie frequently separate on weekends so one can attend Natalie’s cheer competition in one part of the state, and the other can put on a coat and gloves and sit inside a chilly ice rink to watch Nick play.

“We encourage our kids to do what makes them happy,” Corrie said.

If you want more proof of that, look no further than the Hackings’ oldest daughter, Dilyn.

“She’s a welder,” Corrie said. “She melts metal all day.”

So, they feed Natalie’s passion for cheerleading and nurture Nick’s dreams of one day skating for an NHL team.

And when needed, Corrie sits down with Nick’s class planner and makes the necessary adjustments, made possible by PEP.

A Tampa Bay area morning TV show kicked off National School Choice Week by highlighting a family who benefits from a state K-12 scholarship.

Arielle Frett appeared on Fox 13’s “Good Day Tampa Bay” program on Monday with her son, AnyJah, a ninth grader at The Way Christian Academy in Tampa. She said she moved to Florida from St. Thomas, Virgin Islands, in 2017 to find better educational opportunities for AnyJah, who has severe autism.

“No teachers were able to work with him on his level,” Frett told Fox 13 reporter Heather Healy. “Most of his learning in English and math are on fifth and sixth grade levels now.”

A U.S. military veteran and single mother of two, Frett said she would not have been able to afford a private school for her son without the scholarship.

She said AnyJah, who receives the Family Empowerment Scholarship for students with Unique Abilities, is “loved, protected, and thriving” at his school, where class sizes of 10 to 12 students allow for more individual attention. He can also receive his therapies during school.

The segment also featured information about Florida’s robust education choice options. Those include traditional public schools, district magnet schools, charter schools, private schools, microschools, homeschools, virtual schools, and customized education programs that allow parents to mix and match.

“We’ve gone from education and funding through the system to now empowering families by putting the money in their hands and allowing them to make the most appropriate educational decisions for families,” said Keith Jacobs, director of provider development at Step Up For Students, which administers most of the state’s education choice scholarships.

Jacobs has spent the past year working with school districts to provide individual courses to scholarship families whose students do not attend public or private school full time, paid for with scholarship funds. About 70% of Florida school districts are participating.

The scholarship application season for the 2026-27 school year begins Feb. 1. Visit Step Up For Students to learn more and apply.

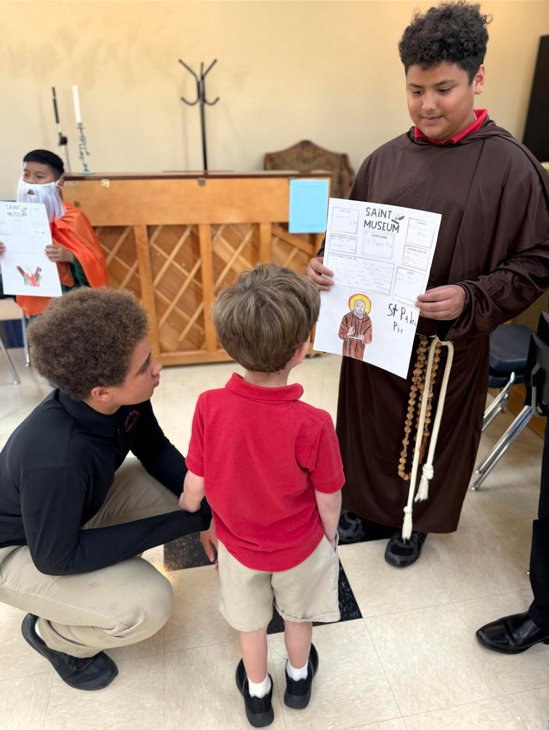

Editor's note: This story is part of our series marking National School Choice Week. We also recognize Catholic Schools Week, which runs concurrently. The scholarship application season opens on Feb. 1. Visit Step Up For Students to learn more and apply.

In 1999, the former school choice scholarship student was 10 years old and living in the Deep South Navy town of Pensacola, Florida. He was being raised by a single mom who worked as a cashier; growing up in a tough neighborhood; and going downhill in a tough public school.

Then, all of a sudden, he was a student at Little Flower Catholic School.

Experiencing the school for the first time, he told me 20 years later, “felt like going to Disney.”

The cathedral was towering. The statue of St. Therese, exotic. Even the classrooms smelled different. “Like Glade,” he said.

The former student didn’t know anything about the scholarship that allowed him to attend. He didn’t know why his mom enrolled him. He just knew that one day he was in third grade at a “bottom of the bottom” school, and then he and his too-big backpack were in fourth grade across town.

Just like that, he said, he went from playing dice and fearing he’d be called a “doofus” for studying, to collecting Pokémon cards and competing academically with the children of doctors and lawyers. For the next two years, the entire community at his new school — the teachers, the other kids, the other families — embraced him.

Two years, it turns out, was long enough for him to affix himself to a path no one else in his family had taken. To high school graduation. To a four-year college. To a good-paying job.

Without this little Catholic school, he said, none of it would have happened.

I met the former student in 2019. That was the 20th anniversary of Florida’s Opportunity Scholarship, the first, modern, statewide voucher program in America. I had set out to find some of the first “voucher kids” and see what happened to them.

Ultimately, I wrote about one of them, but not the kid from Little Flower. His story, though, seared into my brain.

It was uncanny how he so clearly described how this one, brief education intervention so radically changed the arc of his life. He said Little Flower showed him what school was supposed to be like, and, more importantly, what a family was supposed to be like.

A few years later, I would think of the student when choice opponents tried to demagogue scholarship programs because some low-income students use the scholarships only for a short time. They insinuated short-term use proved the poor quality of available private schools, rather than reflect student transience tied to income.

I continue to think about the former student today, as I continue trying to understand why some schools are so much more effective for low-income students. For half a century, we’ve known Catholic schools are among them. It’s another reason I’m grateful Catholic schools in Florida are growing again, and excited about the potential of school choice to reverse the trend lines in other states, too.

The “Catholic school advantage” has made the American Dream a reality for millions of working-class kids, usually at far less cost than public schools. But why?

“Catholic Schools and the Common Good” sought to answer that question. A classic in education research, it was published in 1993, just a few years before Florida launched its first scholarship program. It’s jarring how many school characteristics identified as central to Catholic school effectiveness are so basic.

An orderly environment. High expectations for every student. A focus on academics and character. And above all, pervasive warmth and hope, grounded in a faith that extended a “genuine sense of human caring” to every kid.

Why is it so hard to get more of that?

…

The kid was assigned to his neighborhood school. He and the school struggled. The man he grew up to be described the school and its outcomes this way:

The kids who went there, many of them are either dead or in jail or not successful. It was the bottom of the bottom in a sense. Kids who’ve been generation after generation in a certain mindset. The same cycle. Generational curse. Broken homes. A lost generation of kids with no fathers.

In first grade, he was held back.

“I don’t know if it was because he was slow at that time, or if the teacher didn’t take the time out to teach right,” his mom told me. “I went to school a couple times and asked, ‘What’s going on?’ They said, ‘He’s a good kid. He behaves. He’s trying.’”

But as time went on, the kid began hanging with tougher students. In hindsight, he said, he was “starting to go to a dark place.”

Just in the nick of time, the stars lined up.

Students were eligible for the Opportunity Scholarship if they attended a public school that earned two F grades in four years. The student in Pensacola attended one of those schools.

…

The kid’s mom couldn’t drive him to Little Flower every day. It was a long haul. Her car was unreliable. Her elderly friends volunteered to give her son rides.

They didn’t have much money, but sometimes they’d hand him a dollar for lunch. They told him he had an opportunity other kids didn’t have.

Study hard, they told him. … Stay away from the street … Make your mama proud.

The kid started at a second-grade level academically, even though he was in fourth grade. He said many of his classmates were already doing middle school work. But no one at Little Flower ever made him feel inadequate, he said. His teachers simply gave him more 1-on-1 attention so he could catch up.

Gratitude fueled him. He didn’t want to let down his mom. Or the “old heads” who gave him rides. Or a former teacher from his prior school, who sometimes took him to church and told him, “There’s something special in you.”

Competition fueled him, too. He knew he was behind many of his classmates but was determined not to stay there. Everything about the school, he said, told him he was just as capable.

The former student said he loved the diversity at Little Flower. Working class, middle class, upper class. Mostly white, but with a growing number of Asian students and, thanks to the choice scholarships, more Black students. Increasingly diverse, yet united as a community.

The kid said his new friends invited him into their lives, where he glimpsed a world he’d never seen. Comfortable homes. Nice things. Moms and dads.

“It opened up my mind to think different,” he said, “to understand that just because you come from a certain area, you don’t have to follow that line.”

…

The kid returned to his zoned school for middle school. He didn’t know why. His mom couldn’t remember.

But the lessons from Little Flower stuck with him.

He graduated from high school, attended a four-year college, and earned a bachelor’s degree. He said he loved college, and not just for academics. He was surrounded, he said, by students with “concrete families.”

Just like he was at Little Flower.

“I got to see what a family was,” he said. “A functional family. A healthy family. This is what a family feels like. It gives you spirit … inspiration … warmth … “

Today, the former scholarship kid has a good-paying job. He’s married with kids. He told me his “biggest mission in life is to raise a healthy family.”

Little Flower taught him that, he said, without ever having to say it.

The time has come when we officially recognize National School Choice Week. However, we at Step Up For Students like to say that every week is National School Choice Week.

We are proud that Florida is the national leader in empowering parents to choose the best educational fit for their children. More than half of the state's K12 students used some form of education choice in the 2023-24 school year, according to the Florida Department of Education.

Parents’ ability to direct their children’s education has always been important, but even more so in the past 100 years, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Pierce v. Society of Sisters (1925) gave parents the right to choose between public and private options.

“The child is not a mere creature of the state,” Justice James C. McReynolds wrote in the unanimous decision that the government cannot compel children to attend only public schools.

Catholic schools, which were the target of the law the high court struck down, cheered.

Fittingly, Catholic Schools Week, which we also recognize, is running concurrently this year with National School Choice Week. With its robust statewide choice scholarships, Florida is also a national leader in Catholic school enrollment growth.

National School Choice Week is a non-partisan celebration that encompasses all forms of choice: Traditional district schools, public magnet schools and charter schools, virtual schools, private schools, both religious and secular, microschools, home education and customized learning powered by education savings accounts that can include a mix of public and private programs.

Events are happening across the nation, from capitol rallies to school choice fairs to students in signature yellow scarves performing the official National School Choice Week dance in their classrooms or homes.

Throughout the week, NextSteps will share stories of students and families who have benefited from Florida’s many educational options. You will meet a young hockey player whose Personalized Education Program scholarship has allowed him to travel with his team to compete in international tournaments while keeping up with his schoolwork and educational goals. Ron Matus, Step Up’s director of research & special projects, will share his memories of a former student who was among the state’s first recipients of Florida Opportunity Scholarships pioneered by former Gov. Jeb Bush. A couple of years in a Catholic school were enough to put him on a path to a better life.

We will also bring you a story by a Tampa Bay FOX affiliate of a single parent who was able to send her son, who struggled in other schools with his autism, to a school where he is thriving, with dreams of going to college.

We will cap off the week at the festivities Thursday in Tallahassee, where Step Up representatives will have information about the Feb. 1 season open for 2026-27 scholarship applications.

Even if you aren’t at the rally, you can still learn about the scholarships and apply at www.stepupforstudents.org.

We can’t wait until next week. And the week after. And the week after that.

Because we serve Florida, where choice is the norm for all public education.

By Ron Matus and Julisse Levy

HUDSON, Fla. – In 2022, Joel Hernandez and his wife, Norma Torres, had to find a new school for their then-9-year-old daughter, Fabiola. In their part of Puerto Rico, they felt their options were, at best, limited.

Fabiola is on the autism spectrum. Over the years, her parents visited and/or researched every public and private school in the area that served students with special needs. It was not a pretty picture.

In some, up to 30 students with vastly different learning and support needs were crammed together in the same classrooms. In one, students with a wide range of ages and special needs were grouped in a room that doubled as storage for desks, tables, and other equipment. Yet another was so lacking in security that Hernandez walked from the entrance to the classroom without anybody asking who he was or what he was doing.

In the end, the couple settled on a school that looked good on paper. But it turned out to be a bust, too. It never delivered on promises of regular speech and occupational therapy.

Fighting for Fabiola left the couple drained. Their daughter needed every opportunity to gain skills that would allow her to live as independently as possible as an adult, and it wasn’t happening.

“We spent nights crying,” Hernandez said. “We looked at each other every day and said, ‘What are we going to do?’ “

As things grew desperate, the couple began to consider moving to the states for better educational opportunities, and more specifically, to Florida, where they had enjoyed time on vacation. When they began researching schools in the Sunshine State that served students with autism, one immediately jumped out.

It had Hope in its name.

'I knew it was meant to be'

Hope Ranch Learning Academy is a K-12 school with 250 students an hour north of Tampa.

From the school website, the couple could see a campus awash in moss-draped oaks. To them, it looked calming. The school featured equine therapy, which Fabiola experienced in Puerto Rico and loved. It was also a Christian school, which was very important to the family.

Incredibly, Hernandez and Torres also saw a familiar face on the website, a girl who had been Fabiola’s friend years prior.

“God intervened,” Hernandez said. “I knew it was meant to be.”

The couple contacted the girl’s family, who referred them to a school administrator. The woman told them that Hope Ranch had a long waitlist — it’s now more than 80 students — and they had to be Florida residents to get on it. She asked, “Do you really want to move because of the school?”

“That was the a-ha moment,” Hernandez said. “We said, ‘In Puerto Rico, we have nothing for our daughter. We have to move.’”

Private school boom, scholarships, draw families

Families are moving to Florida because of its schools and school choice.

It’s not just the abundance of state choice scholarships, which average $8,000 or $10,000 each and are now available to every family. It’s the entire, choice-driven system. Florida’s education landscape is becoming more diverse and dynamic by the day, as the families of 500,000 students using scholarships (and growing) shape it with their preferences.

In the past 10 years alone, the number of private schools in Florida has grown by a third. That’s a net gain of more than 700 private schools, which is more than 39 states each have, period. And what’s more impressive than the number is the variety.

Schools like Hope Ranch, which was a semi-finalist for the Yass Prize in education innovation, are not anomalies. High-quality schools serving students with special needs have emerged in every corner of the state, and some are now drawing families from out of state. At the North Florida School of Special Education, for example, the families of 24 students moved from out of state, including this family from Maryland.

At Hope Ranch, a half-dozen families have even moved from other countries or Puerto Rico.

Equine therapy and transition program set Hope Ranch apart

In Puerto Rico, Hernandez taught marketing at a college and sold beauty supplies. Torres worked as a nail technician. Moving to the States obviously would mean leaving friends and family and starting over with new jobs, a new house, everything. But Fabiola’s future depended on it.

In November 2023, the family and their three dogs moved into their new home, 12 miles from Hope.

Since Fabiola couldn’t attend the private school right away, her parents enrolled her in the neighborhood public school. It turned out to be excellent. One teacher in particular paid extra attention to Fabiola and made sure she got the help she needed, including a full-time, 1-on-1 assistant.

“There’s always an angel over Fabiola,” Hernandez said.

Hope Ranch, though, remained ideal. Besides the equine therapy program, the school operates a highly regarded transition program that prepares students for independent living as adults. In December, the Yass Prize awarded Hope founders Jose and Ampy Suarez an alumni grant, so they could build a separate high school campus and expand the transition program.

Hernandez periodically checked in with Hope to see how much the waitlist was shrinking. Finally, in June 2025, the administrators invited the family to the school so they could share the good news in person.

Fabiola was in.

Family credits school choice scholarship for making Hope Ranch affordable

Classes started in August. Just a few months later, Hernandez said the change in Fabiola has been “astronomical.”

Fabiola smiles more. She’s happy when she wakes up. She’s happy on the way to school.

She’s more independent, confident, communicative. She doesn’t cover her face as much as she used to. She tries to verbalize more. She makes eye contact more often.

“She wants to play with other children now,” Torres said. “She feels included. They grab her hand and say, ‘Come with us.’ “

Last month, Fabiola and the other Hope Ranch students performed a stage version of “The Little Drummer Boy” for students at a nearby high school. Fabiola was on stage for an hour.

“I know she has to progress more,” Hernandez said, “but we feel very good.”

None of this would have been possible without Florida’s choice scholarship, he said. The family couldn’t afford Hope Ranch without it.

The school told the family about the scholarship. But Hernandez couldn’t believe how easy it was to get.

In Puerto Rico, he and Torres were accustomed to filing all kinds of education requests on Fabiola’s behalf and waiting long stretches for answers. With the scholarship, they got the award notice within 24 hours of applying. “I thought I was going to have a heart attack,” Hernandez joked.

“We had this in our dreams, but we didn’t know it could come true. Florida and Hope were a dream come true,” Hernandez said as he started to cry.

“I’m sorry I have to cry, but it’s very emotional,” he continued. “In Puerto Rico, all we had were problems” with Fabiola’s education. “Here we have solutions.”

Some quotes in this story were translated from Spanish to English with the assistance of Julisse Levy, director, head of business Initiatives, Federal Scholarship Tax Credit, at Step Up For Students.

TAMPA, Fla. — The words on the trophy read “Future Philanthropist,” and Mrs. Finley, who taught fifth grade that year, cried when she presented it to Andrew Weber during graduation.

Andrew smiled at the memory.

“It was one of the highlights of my elementary school career,” he said. “Mrs. Finley said I was one of her favorite students. That meant a lot to me.”

So did receiving the trophy, which still holds a place of honor on his nightstand.

“It made me realize my potential and how I can help others,” Andrew said.

Almost seven years later, Andrew, a 17-year-old senior, is nearing another graduation, this time from Jesuit High School, the Catholic school in Tampa he attends with the help of a Florida education choice scholarship.

The altruistic nature Mrs. Finley saw in Andrew when he was in elementary school blossomed during the ensuing years.

Jesuit’s mantra is “Men for Others,” and Andrew embodies that.

“He does 100%,” said Andy Wood, Jesuit’s athletic trainer and track and field coach, and the school’s former director of community service. “Andrew is one of our top students. And when you talk about a total package, including his community service work, being a student athlete, he's what we envision our seniors being at graduation.”

Andrew volunteered for eight service organizations while in high school.

He made two trips to an orphanage in Guatemala with his Jesuit classmates, feeds people at Metropolitan Ministries, and delivers Meals on Wheels with his mother, May.

He’s volunteered for the Faith Café, the Young Men’s Service League, Teens United Florida, the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, and the Ryan Nece Foundation, a non-profit founded by a former Tampa Bay Buccaneer that empowers teens to become leaders through volunteering.

Andrew traveled to Asheville, North Carolina, last June with the Ryan Nece Foundation to help families with home repairs still needed after the flooding caused by Hurricane Helene.

He is a pole vaulter on the track and field team, and in his spare time, he plays the piano at a local nursing home.

As a junior, Andrew received the Anne Frank Humanitarian Award from the Florida Holocaust Museum in Tampa for his outstanding humanitarian efforts.

Andrew’s parents, May and Tim, raised him and his older sister, Elise, to be community-minded. Elise, now a sophomore at the University of Georgia, also volunteered for the Ryan Nece Foundation while in high school.

“As his parents, we always wanted Andrew to be very involved in a lot of things and explore different passions, and luckily for him, many of those passions really stuck,” May said.

Andrew set the foundation in elementary school when he sold lemonade, handmade crafts, and rocks (crystals and gems) from a stand in the front yard of the family’s Tampa home. He said he would raise maybe $100 over several weeks and donate the money to charities such as Dogs Inc (formerly Southeastern Guide Dogs).

“I was 8,” he said. “I felt the money could benefit other people more than it could benefit me.”

“His heart was always generous,” May said.

For a teenager as service-oriented as Andrew, he certainly found a home at Jesuit, where students are required to complete a minimum of 150 hours of community service during their four years. Andrew, though, has accrued more than 500.

Yet, the decision to attend Jesuit was not easy.

“It was a very hard decision,” Andrew said.

His options were these: his district school, where Elise was a rising junior and where a lot of his friends were headed, or Jesuit, an all-male parochial school with demanding academic standards.

For help, Andrew turned to his role model: his big sister.

“She said, ‘Andrew, if you pass up this opportunity, you might regret it for the rest of your life.’ So I said, ‘I'm going to listen to you,’” Andrew said.

Thinking back on it now, Andrew added, “She was right.”

He has no regrets.

Andrew’s two trips to Orfanato Valle de Los Angeles (the Valley of the Angels orphanage) outside of Guatemala City with his classmates opened his eyes to how fortunate he is to live in America.

The orphanage did not have air conditioning, and hot water was spotty at best.

Wi-Fi? Yeah, right.

“I just put down my phone and started living in the environment, living how these kids live, and I realized that life can be fun,” Andrew said.

The Jesuit students spent nine days with at-risk children, teaching them English and about their faith.

Andrew called the experience “life-changing.”

“In Tampa, we really live in a bubble,” he said. “There are things I don’t take for granted anymore.”

Like AC, hot water, and a strong Wi-Fi signal.

And how a simple act of kindness can make a world of difference in someone’s day.

During the summers, he and his mom deliver Meals on Wheels to older adults and others unable to leave their homes without difficulty. It’s a bonding moment between the two, quality time spent together for a mom and her son.

“It's probably my favorite thing that we have done together,” May said.

“It’s the favorite thing that I do,” Andrew said.

They don’t rush through their route. Instead, they spend a few minutes at each stop, checking on the people receiving the meal, making small talk, and letting them know they matter.

When they first started delivering the meals, May told Andrew: “We’re probably the only people they're going to talk to that day, so even though this is sort of a blip on your radar, this is their day; this is their weekend; this is their week. So, make it count.”

Andrew took that lesson to heart.

A man for others.

“I feel like if I were in that situation where I needed help, I obviously want someone to do the same thing for me,” he said. “Spreading Jesuit’s values across what I do is a big part of why I do it. What I've learned here, it really propels me to do what I do in such a great way.”

Andrew wants to major in business in college. Where? He hasn’t decided. His choices are the University of Georgia, the University of Tennessee, Boston College, and Florida State University.

Where will that major lead him? He’s not sure.

“I can tell you it will be with people,” May said. “Whether it's finance or accounting, marketing or entrepreneurship, his love is working with people. I think it's just what comes naturally to him. He motivates people and makes people feel better about themselves. So, that’s my prediction.”