Just what is a microschool? The Christian Science Monitor takes a thorough and balanced look at the growing movement.

Ask a dozen microschool leaders to describe their schools, and you’ll likely receive a dozen slightly different responses:

Montessori-inspired, nature-focused, project-based, faith-oriented, child-led, or some combination of other attributes. They may exist independently, as part of a provider network, or in partnership with another entity such as an employer or a faith organization. Their schedules vary, too. Some follow a typical academic calendar, while others operate year-round, and some allow students to attend part time.

In other words, there is no one-size-fits-all definition for microschools. But, in general, they’re intentionally small learning environments. They often serve fewer than 30 students total and operate as learning centers to support home-schooled students or as accredited or unaccredited private schools. Their exact designations differ based on state laws.

To that description, I'd just add one more layer of nuance: Many microschools operate in partnership with public schools, for example, by sub-contracting with districts or charter schools, or as affiliates of longstanding private education institutions, like the microschools operated by the Catholic Diocese of Los Angeles.

Their diverse missions and configurations share something in common: divergence from the norm in public education. I have yet to encounter a microschool whose founders describe their work in terms that in any way resemble: We offer conventional schooling, only better.

Microschools break from convention, by design. Their breaks from convention could relate to content (they may offer religious instruction that isn't possible in public schools), pedagogy (they might embrace classical education or student-led learning), the identities of students they aim to serve (as in the case of the Black Mothers Forum in Arizona), or the structure of schooling (by bringing together students of different ages or offering hybrid and part-time schedules).

This is where their small size matters. A microschool can make bold and specific choices about what it offers, because it often only needs to attract a small number of like-minded students and educators. This allows microschools to exist in communities that could not possibly muster the numbers to sustain traditionally sized schools aligned to their philosophy or value proposition.

In rural New Hampshire towns where it wouldn't be economical for a conventional private or charter school to offer an alternative to existing public schools, 10 students can sign up with a learning guide to form a Prenda microschool. Under Prenda's flexible, student-led instructional philosophy, they need not even be exactly the same age. The Black Mothers Forum operates a network of microschools in Greater Phoenix, where just 7% of public-school students are Black—less than half the percentage in public schools nationally. These and countless other examples are able to offer particular groups of students something truly different, without having to worry about sanding down the edges of their identity to attract a critical mass.

To be sure, some microschools could grow to the point that "micro" becomes a misnomer. Some could operate "schools" that serve groups of students in multiple locations, or simply enroll enough students that they rival the size of a more conventional learning environment.

Thanks to their ability to operate at a small scale, to bring students together in ways that defy the conventions of age-based grading, and sometimes to blur the lines between schooling and homeschooling, microschools have the potential to enable a new level of pluralism and diversity in education.

Prenda now operates in six states, partnering with state-accredited institutions to provide a tuition-free education option. Meeting in homes and other flexible locations, small groups of K-8 students engage in project-based learning and progress at their own pace under the direction of guides who come from the ranks of parents, teachers, and other community members.

With rising inflation and a stock market on the rocks, any big investment is worth watching. And with researchers reporting poor returns on student achievement in assigned schools during the pandemic, this makes any investment in education even more notable.

So with venture capitalists betting big on Prenda last week, committing $20 million to advance the company’s activities, parents and families around the country should take notice.

Prenda forms “microschools,” which are what they sound like: small learning communities of 10 students or fewer. The company caught parents’ and lawmakers’ attention during the pandemic as traditional schools were closed for in-person learning. Families looked for alternatives, and the learning pod and microschool models offered hope.

With a learning pod, parents led small groups of their own children, along with the children of their friends and neighbors, in learning groups that resembled homeschool co-ops. Microschools are similar, though organizations such as Prenda and Acton Academy Affiliate Network help create these small schools that are similar to reduced-size private schools.

Not all the attention from lawmakers was good. In fact, policymakers around the country tried to impose rules and regulations that treated microschools and learning pods like at-home daycare operations. Daycare regulations can be overly bureaucratic and apply to children who are younger than school age, making the rules a poor fit for microschools and pods.

The collision of heavy-handed regulation and increasing learning pod enrollment risked crushing these viable civil-society responses to school closures during COVID.

Some state officials recognized the mismatch between daycare rules and the new learning innovations, though. In West Virginia, lawmakers adopted a proposal earlier this year that allows for the creation of learning pods and microschools. State officials defined learning pods as “voluntary” associations of parents that may or may not involve tuition payments, allowing parents to educate their children at home and the children of friends and neighbors who are not satisfied with the options at an assigned public school.

Parents will measure student progress with nationally norm-referenced tests or other assessments, providing transparency for families and taxpayers. West Virginia’s proposal also protects the creation of microschools, in the form of small, private schools.

Nationally, public school enrollment has dropped by 1.2 million children since 2020. In West Virginia, public school numbers have fallen by 21,000 children since 2017. Whether this signals widespread parent dissatisfaction with assigned schools or that students are falling through the cracks – or both—parents and children need options outside the assigned system.

Which brings us back to learning pods and Prenda.

The company has expanded well beyond Arizona today and serves some 3,000 students in six states across 300 microschools. The company has announced that it will be expanding into other states. For West Virginia families, the new learning pod and microschool law will not jeopardize families who choose to homeschool. But families can also create their own learning pod, and parents can apply for the state’s new Hope Scholarship, an education savings account option that also originated in Arizona. Families should even be able to use the Hope Scholarship to create a microschool, which makes Prenda’s expansion so notable.

Federal officials have sent some $200 billion in taxpayer resources to schools during the pandemic, and, as of last fall, some $150 billion remained unspent—all while achievement scores and enrollment are falling.

Meanwhile, savvy parents are now making more choices about how and where their children learn, in West Virginia and elsewhere. The savvy investors are watching.

On this episode, Ladner speaks with the founder of a Phoenix-based organization dedicated to erasing systemic inequities and ending the “school-to-prison” pipeline for Black children.

On this episode, Ladner speaks with the founder of a Phoenix-based organization dedicated to erasing systemic inequities and ending the “school-to-prison” pipeline for Black children.

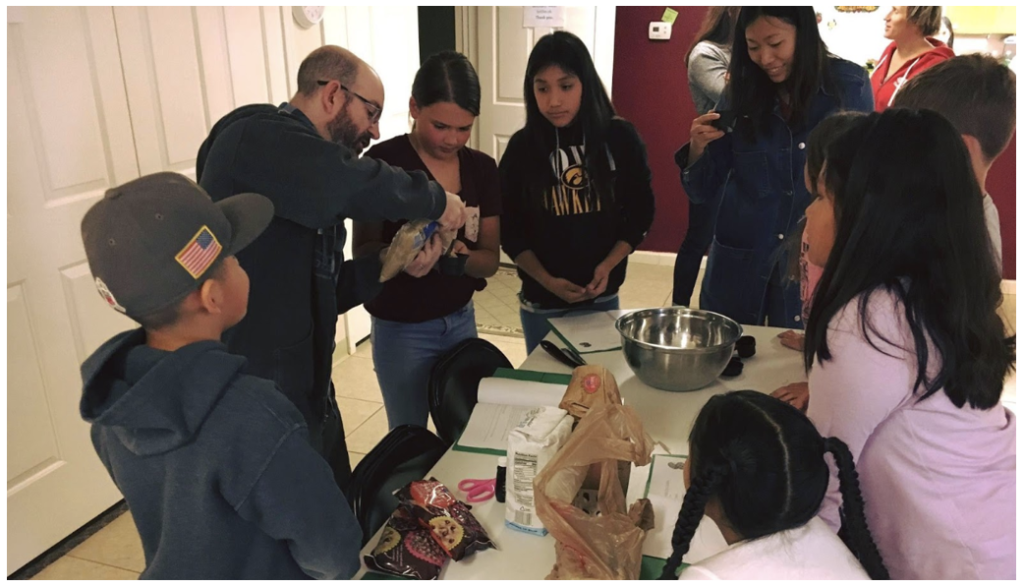

In partnership with the Arizona-based microschool organization Prenda, Black Mothers Forum facilitates seven microschools, each serving 10 students or less in the Phoenix area. The group aims to grow to as many as 50 microschools.

Ladner and Wood discuss the ways in which the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated inequities for Black children, what led Black Mothers Forum to explore microschooling, and enthusiastic parent response to the microschool environment, which they say allows their children to thrive in a safe space.

"Most children in traditional settings are told what they're doing that day. They may not feel like doing it that way and might not do as well. We’ve found our children excel when they get a chance to choose what part of their goals they want to fulfill that particular day, and they do it well."

EPISODE DETAILS:

Empowered Minds Academy is an in-home microschool in Maricopa, Arizona, based on the Prenda model of 5-10 students led by mentors, or guides, who engage children in collaborative activities and creative projects.

Editor’s note: This post from Mike McShane, director of national research at EdChoice and a reimaginED guest blogger, appeared Thursday on forbes.com.

The Roman philosopher Seneca is quoted as saying that “luck is what happens when preparation meets opportunity.”

When the coronavirus hit Arizona and parents were looking for options outside of their closed traditional public schools, they were lucky to find a proliferating network of microschools. But that lucky moment was years, if not decades, in the making.

In a new paper for the Manhattan Institute, I examine the phenomenon of microschooling in Arizona.

After hearing from several parents who found microschools to be a godsend after they grew frustrated watching their school boards and administrators dither and prevaricate on COVID policies, I wanted to answer a basic question: Why here?

To answer that question, we have to look back more than two decades into Arizona education policy.

Starting in the mid-1990s, Arizona pushed for greater school choice, with the legislature passing a charter school law and an open enrollment law, followed just a few years later by one of the nation’s first tax-credit scholarship laws. Over the intervening years, the state has created four more private school choice programs, including a nation-leading education savings account in 2011.

To continue reading, click here.

Prenda launched in 2018 with seven students. The network had grown to more than 400 microschools by fall 2020.

Editor’s note: To learn more about education choice in New Hampshire, check out SUFS president Doug Tuthill’s podcast with New Hampshire state Rep. Glenn Cordelli here.

Signaling its continued support for education choice and parental empowerment, the New Hampshire Department of Education has announced that four districts – Bow, Dubarton, Fremont and Haverhill – have been awarded Recovering Bright Futures Learning Pods grants from the state to address learning loss due to the pandemic.

The Department has partnered with Prenda, a tuition-free network of microschools, to create small, in-person, multi-age groupings where students can learn at their own pace, build projects and engage in collaborative activities. Prenda will utilize the grant funds on a per-pupil basis to serve Learning Pod enrolled students, who will remain enrolled at their district school.

Each learning pod will be supported by a certified learning guide and will follow a project-based learning model. All families can access the learning pods as space allows.

The concept of learning pods may be new to many, New Hampshire Education Commissioner Frank Edelblut said, but they’ve already served more than one million students across the country.

“Learning pods are particularly helpful to students who have experienced learning loss and will thrive with more individualized attention,” Edelblut said.

Learning programs in district learning pods have been aligned with New Hampshire Academic Standards and adapted to individual students. Prenda will be responsible for providing quarterly updates to the district on student performance criteria and attendance will follow district practices.

All New Hampshire school districts, including traditional and public charter schools, as well as home education families, are eligible to participate in the District Learning Pod program. The Department expects additional school districts in the state to sign on for the program.

On this episode, Tuthill catches up with the founder and CEO of Arizona-based Prenda, an organization on the front lines of the micro-school tsunami that has soared during the global pandemic.

On this episode, Tuthill catches up with the founder and CEO of Arizona-based Prenda, an organization on the front lines of the micro-school tsunami that has soared during the global pandemic.

Smith describes how these home-learning environments, catering to fewer than a dozen similarly aged students, are gaining traction among families looking for creative education options. Amidst rampant uncertainty and accelerated changes to public education, micro-schools and other smaller “pod” education formations are sweeping the country – and blending mastery-based education with peer collaboration.

Smith discusses Prenda’s expansion into Colorado and his team’s experiences in working with partners to bring micro-schools to as many communities as possible, noting he’s inspired by those in district schools who see the importance of adding micro-schools to their portfolio of options. He believes there are passionate visionaries and leaders working inside traditional systems, stepping up and taking risks against the wishes of institutional pushback.

"The genie is out of the bottle (on micro-schools) ... Families are reporting their child is engaged, and the format really works ... A safe comfortable environment right in the neighborhood can be empowering and kids can come out of their shell.”

EPISODE DETAILS:

· Prenda’s most recent year and lessons learned during the pandemic

· Assuaging parents’ fears about shifting from factory-model education and toward intrinsic, organic learning

· The regulatory environment in particular states and Prenda’s plan for expansion

· How school districts have stepped up to encourage micro-schools

· The challenges that lie ahead

To listen to Tuthill’s earlier podcast with Smith, click HERE.

Music producer DJ Khaled with his children, Asahd, 4, and Aalam, 10 months

DJ Khaled, who has produced 18 Top 40 hits and eight Top 10 albums, earned a feature in the Dec. 2 issue of People magazine for starting a pandemic pod for his 4-year-old son and his son’s classmates.

“In March, when Asahd's preschool sent everybody home, I was doing the Zoom classes with him every single day,” the article quotes Khaled’s wife, Nicole Tuck. “I thought to myself, 'This cannot be the best we can do!’ So, I organized a learning pod at our house with other quarantined families. We have seven kids and two teachers, and it's absolutely amazing.”

Having a seven-child school with two teachers in a guest house may strike some as being a bit out of reach of the average American family. Phillip II of Macedon created a one-to-one pod for his son with Aristotle, and that worked out great for Alexander, but alas, it isn’t easily replicated. Public policy, however, can make education like Khaled and Tuck are providing broadly available.

Many families would struggle to hire one, much less two teachers, using their own funds. But in Arizona, micro-school genius Prenda partners with districts, charters and families who use education savings accounts to form micro-school communities. When the pandemic hit, 700 students were learning through Prenda, but in the ensuing months, that number has greatly increased.

District, charter and ESA enrollment allows students to access their K-12 funds to pay an in-person guide and provide both in-person and distance learning. A growing number of school districts, cities and philanthropies have been helping to create small learning communities around the country as well. The Center for the Reinvention of Public Education has started keeping a tally of these efforts, which you can view here.

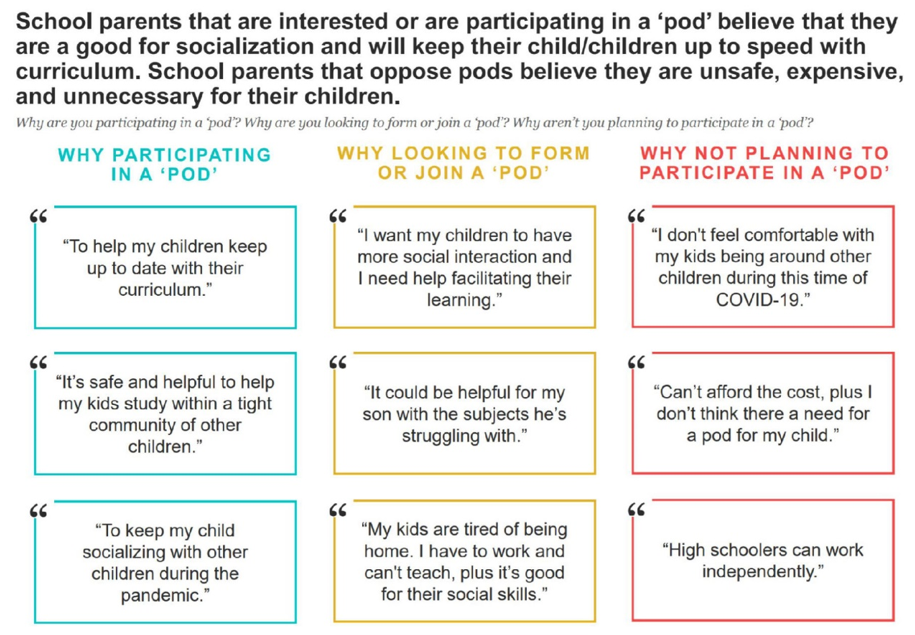

Khaled is hardly alone in his enthusiasm for micro-schools. A recent survey of parents conducted by Ed Choice found that 35% were participating in a pod; another 18% reported interest in either joining or forming a pod. Meanwhile, a recent parent poll conducted by the National Parents Union found almost two-thirds of those surveyed said they want schools to focus on new ways to teach children as a result of COVID-19 as opposed 32% who said they want schools to get back to normal as quickly as possible. Fifty-eight percent said they want schools to continue to provide online options for students post-pandemic.

What is thy bidding my master?

What is thy bidding my master?

I have felt it.

It will be very difficult to conceal, but if we would agree to reopen the large schools …

Yes, my master…

What about the organizations that are providing devices and public funding for instructors? The ones addressing the equity issues rather than merely talking about them?

A recent EdChoice poll found that about one-third of parents who responded to its survey are participating in pandemic pods, and that a majority – 53% – either are participating or looking to form a pod. The following graphic accompanied poll results, providing parents’ explanations for why they are participating, why they’re wanting to begin participating, or why they are not planning to participate in the practice.

Last week, Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey hosted Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos in Phoenix. Districts, charter and mico-school leaders and parents spoke about innovative school models, one of which was a school formed by members of the Black Mother’s Forum in cooperation with Prenda, an Arizona-based micro-school organization.

The Wall Street Journal noted an opposition report to micro-schools delivered to the National Education Association concerning these types of schools in general and Prenda in particular.

“The Opposition Report has documented widespread support for micro-schools,” it read. The NEA opposition report cites an expert who thinks micro-schools can “address some of the structural limitations of homeschooling,” such as parents’ work obligations, and — this is Prenda’s innovation — take advantage of school choice programs to “alleviate some equity issues” posed by the cost of hiring your own teachers. The combination could make home education feasible for millions more families.

The NEA opposition report goes on, predictably, to raise concerns about pods increasing achievement gaps. The Wall Street Journal sagely notes this view goes beyond the nonsensical.

It’s a strange pitch from the teachers union: micro-schools are dangerous — they help their students learn more! This seems like a reason to broaden access, not restrict it. And that’s what Prenda has done by eliminating tuition: make micro-schools accessible to low-income families.

So, if you are scoring at home, the NEA opposes public schools reopening. It also opposes parents innovating to provide their children with in-person instruction and socialization due to equity concerns. If someone actually addresses equity concerns by paying the in-person instructor, providing computer and internet access, they are really against it.

If parents are watching all of this, including the harm it is doing to the education of their children, I can imagine their reaction might look something like this:

Editor’s note: This commentary from Bruno V. Manno, senior adviser for K-12 Education at the Walton Family Foundation, explores the myriad ways the global pandemic is birthing impressive innovations and alternatives so learning can continue.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Bruno V. Manno, senior adviser for K-12 Education at the Walton Family Foundation, explores the myriad ways the global pandemic is birthing impressive innovations and alternatives so learning can continue.

The COVID-19 calamity is motivating families to seek alternatives to their child’s current school and inspiring entrepreneurs to start new enterprises that help families manage this unique situation.

As luck would have it, public and private school choice policies enacted in many states over the last 30 years advance this innovation and invention. Meanwhile, some governors are using their state’s new COVID-19 federal dollars to give parents financial support when needed as they move to these new education programs.

Three of the newer innovations parents are choosing are micro-schools, family PODS and virtual charter schools.

Micro-schools are one-room schoolhouses, typically mixed-age groupings of 15 students or less that meet in homes, churches, community centers or workspaces. They often use today’s technology to support instruction, with teachers — or other learning guides — using different instructional approaches, including place-based and experiential learning.

Some micro-schools are private and charge tuition, though 29 states (plus the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico) have school choice polices that allow families to use public dollars to pay for private school expenses. Other micro-schools are tuition-free public schools; they are created using some aspect of a state’s charter school law.

Arizona-based Prenda, a network of micro-schools, has grown from seven students in one neighborhood in 2018 to more than 200 schools. Its website traffic increased 737% in June compared to activity for June 2019. The organization works with public charter schools to provide tuition free micro-schools. It also accepts funds from Arizona’s Education Savings Accounts program, which allows families to use public dollars for private school costs, tutoring, online learning and other educational expenses.

Another innovation is the now much-discussed Parent Organized Discovery Sites, or PODS, typically engaging three to six families who employ one teacher for their kids. Alternatively, parents teach, hiring a college student or other adult to assist. Some PODs provide scholarships for low income families. And in some states, educational expenses associated with PODs can be paid for with public dollars.

Pandemic PODS combine tutoring and childcare so students socialize and learn with friends. A Facebook post documents how “within 48 hours … thousands of parents [created] Facebook groups to form … PODS.” The San Francisco school district will open 40 district PODS in libraries and community centers this school year.

In Columbus, Ohio, the YMCA is offering PODS for students ages 5 to 16 who are attending school virtually. Students can arrive as early as 6 a.m., with learning sessions starting at 8 a.m.

Public charter schools are another option, coming in many forms, including online learning. Families are choosing virtual charters as “brick and mortar” schools remain closed or because they’re wary of sending kids into school buildings.

Oklahoma’s Epic Charter Schools is a virtual school enrolling 38,026 students. It’s the largest school system in the state — surpassing Oklahoma City’s and Tulsa’s districts — adding up to 1,000 students a day. Students who enroll in Epic’s online program have access to a $1,000 “learning fund” to use for everything from karate lessons to art classes. The school manages the money and parents must choose from approved vendors.

Meanwhile, Florida Virtual School is a tuition-free school that works with public, private, charter and homeschool families and school districts nationwide. It has seen an increase of 64,107 course requests in its Flex program since July 1, representing an increase of 93 percent. Full-time applications have increased by 5,738, or 177%, over the prior year since registration opened in March.

New enterprises are also being founded.

SitterStream is a startup created at the beginning of the pandemic. It offers on-demand babysitting and tutoring to students, individually or in PODS. It has partnerships with small and large businesses who provide these services to employees, with Amazon one of their corporate clients.

Transportant, a high-tech school bus company, makes “school buses as smart as your phone.” With the onslaught of the pandemic, it began working with school districts to make buses rolling Wi-Fi hotspots. It now provides high speed internet services for an entire street or apartment building to students who lacked access.

During the pandemic, states also are providing financial support for families seeking new education options for their children. The federal CARES Act provides discretionary funds for governors to support innovative education programs and services, fostering creativity and enterprise.

Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt is using $30 million from the CARES Act’s Governor’s Emergency Education Relief Fund to create a $12 million “Learn Anywhere Oklahoma” program so students can access online content with a teacher; an $8 million “Bridge the Gap” digital wallet program offering $1,500 to more than 5,000 low income families to purchase curriculum content, tutoring, and technology; and a $10 million “Stay in School” fund providing up to $6,500 to over 1,500 low income families with a pandemic-related job loss so their children remain in their current private schools.

Governors Henry McMaster of South Carolina, Chris Sununu of New Hampshire and Ron DeSantis of Florida announced similar programs for low-income families wanting to enroll their child in a private school.

COVID-19 has turned school re-openings into disarray. But creative and determined parents, entrepreneurs and policy leaders are responding with impressive innovations and alternatives so learning can continue.