Public education in the United States is transitioning from its second to third paradigm.

Paradigm shifts in public education occur when larger societal changes force public education to change to meet these new conditions. Current technological advances and the accompanying social changes are pushing public education into a new paradigm and a third era.

To best meet society’s current and future needs, this third paradigm aspires to provide every child with an effective and efficient customized education through an effective and efficient public education market.

A paradigm: The lens through which communities do their work

In his 1962 book, “The Structure of Scientific Revolutions,” Thomas Kuhn described a paradigm as the lens through which a community’s members perceive, understand, implement, and evaluate their work. A paradigm includes a set of assumptions and associated methodologies that guide how communities construct meaning and determine what is true and false and right and wrong.

A paradigm shift occurs when inconsistencies, which Kuhn called anomalies, begin to occur, and some community members begin to question their paradigm’s veracity and effectiveness. As these anomalies accumulate, community members begin proposing new ways of understanding and implementing their work and a prolonged contest emerges between the existing paradigm and proposed new paradigms. If a majority of the community ultimately decides a new paradigm enables them to resolve the anomalies and better understand their discipline, this new paradigm is adopted. In scientific communities, Kuhn calls these paradigm shifts scientific revolutions.

Paradigm shifts are disruptive and revolutionary because they require community members to reinterpret all their previous work and adopt new ways of conducting and evaluating their future work. Senior community members are particularly resistant to changing paradigms because their status comes from applying the existing paradigm over many years. Consequently, paradigm changes are rare and require several decades to complete.

Albert Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity (GTR) was a new physics paradigm that challenged Newtonian mechanics and Newton’s law of universal gravitation (i.e., the dominant physics paradigm at the time). It took over 40 years before GTR gained wide acceptance among physicists. Einstein never won a Nobel Prize for GTR because the Swedish physicists on the Nobel committee refused to accept his new paradigm.

Although Kuhn’s work focused on the role of paradigms in scientific communities, his description of how paradigms function and change is relevant for all communities, including public education. The struggle in U.S. colonial times to transition from a monarchy to a democracy was a paradigm shift. It was a revolutionary change in how government works, was fiercely resisted by those in power, and took decades to complete.

Public education’s first paradigm

Public education’s first paradigm began before the United States was a country, when the Massachusetts Bay Colony enacted the “Old Deluder Satan Act” to ensure the colony’s young people learned scripture. As the name of that early legislation implies, this first era prioritized basic literacy and religious instruction. Most children were homeschooled, and formal instruction tended to be ad hoc, improvised, and organized around the agricultural calendar.

Religious organizations provided most of the structured instruction outside the home in the 1700s and early 1800s. Children and adults attended Sunday schools, and communities organized what today we would call homeschool co-ops, which allowed rural children to receive instruction when their chores permitted.

The federal government supported public education through the U.S. Postal Service by subsidizing the distribution of magazines, pamphlets, books, almanacs, and newspapers, and establishing post offices in rural communities. By 1822, the U.S. had more newspaper readers than any other country.

Public education’s first paradigm started failing in the early 1800s as innovations in transportation and communications began connecting the country and promoting more industrialization and urbanization. About 90% of Americans lived on farms in 1800, 65% in 1850, and 38% in 1900.

This transition from rural to urban created childcare needs. Increased industrialization necessitated a more highly skilled workforce. And concerns about social cohesion grew as the growing country welcomed immigrants from Ireland and later from Southern and Eastern Europe. These were demands the informal, decentralized, and family-driven first public education paradigm was ill-equipped to meet.

Public education’s second paradigm

In 1852, Massachusetts passed the nation’s first mandatory school attendance law. This accelerated public education’s shift from its first to second paradigm.

The massive influx of European immigrants beginning in the 1830s was a primary reason Massachusetts decided to make school attendance mandatory. The U.S. experienced a 600% increase in immigration from 1840 to 1860 compared to the prior 20 years. Most of these immigrants were illiterate, low-income, and Catholic. Massachusetts’ mandatory school attendance law was intended to help turn these new immigrants into “good” Americans, meaning they needed to be literate, financially self-sufficient, and well-versed in Protestant theology.

Protestant hostility toward Catholic education in the U.S. continued deep into the following century and included the infamous Blaine Amendments that many states adopted in the late 1800s to forbid public funding of Catholic schools, and the 1922 constitutional amendment in Oregon that required all students to attend Protestant-controlled government schools.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled the Oregon amendment unconstitutional in its 1925 decision Pierce v. Society of Sisters, ensuring every American family had the right to choose public or private schools for their children. This ruling would later help make public education’s transition to its third paradigm possible.

By 1900, 31 states had passed mandatory school attendance laws. While these laws were not initially well enforced, they did significantly increase school attendance, which created management challenges.

As David Tyack chronicles in “The One Best System,” a history of how this first paradigm shift unfolded in America's cities, a new class of professional administrators, known as schoolmen, set out to modernize public education practice and infrastructure. One-room schoolhouses serving students were no longer adequate, so public education began adopting the mass production processes that enabled industrial manufacturers to create large numbers of products at lower costs. The most famous example was the assembly line that Henry Ford created to mass produce affordable Model Ts.

This new industrial model of public education replaced multi-age grouped students with age-specific grade levels that functioned like assembly line workstations. Just as Ford’s assembly line workers were taught the skills necessary for their workstations, public school teachers were trained to teach the skills associated with their assigned grade level, and children were moved annually from one grade level to the next en masse.

Mississippi became the last state to pass a mandatory school attendance law in 1918. By then the bulk of multi-aged one-room schools were being replaced with larger schools that reflected the best practices of 19th century industrial management. This was the paradigm through which government, educators, families, and the public were now seeing and understanding public education. This change marked U.S. public education’s second paradigm.

Ford famously told customers they could have any color of Model T they wanted provided it was black. Public education adopted this one-size-fits-all approach to increase efficiency. Car consumers began demanding more diverse options over the next several decades, and so did public education consumers. The auto industry diversified its offerings much quicker than public education because it faced competitive pressures the public education monopoly did not. But in 1975, President Gerald Ford signed the Education for All Handicapped Children Act, which required all school districts to begin adapting instruction to serve special needs students. This was the first instance of government requiring public education to provide a large group of students with customized instruction.

Public education’s third paradigm

This expansion of instructional diversity accelerated in the late 1970s and early 80s as school districts started creating magnet schools to encourage voluntary school desegregation. The school district in Alum Rock, California even experimented with a short-lived voucher program that fostered an ecosystem of small, specialized learning environments that today would be called microschools.

Most of the beneficiaries of early magnet schools were white middle-class and upper middle-class families who were attracted by the additional resources and high-quality specialized instruction. But magnet schools created for desegregation could serve only a limited number of students. In response to political pressure from influential constituents, school districts began creating magnet schools unrelated to desegregation, which expanded and normalized specialization and parental choice within school districts and accelerated the transition to public education’s third era.

Florida added significant momentum to this transition with the passage of its 1996 charter school law, the founding of the Florida Virtual School in 1997, and the 2001 creation of the nation’s largest tax credit scholarship program.

Two decades later, the COVID-19 pandemic further hastened public education’s current paradigm shift. Magnet schools, virtual schools, charter schools, homeschooling, open enrollment, homeschool co-ops, and tax credit scholarship programs were already expanding nationally when COVID arrived in March 2020. The pandemic turbo charged the growth of these options and newer options such as microschools, hybrid schools, and education savings accounts (ESAs).

Just as 19th century innovations in communications, transportation and manufacturing led to public education’s first paradigm shift, the rise of digital networks, mobile computing, and artificial intelligence are transforming all aspects of our lives, including where and how we work, communicate, consume media, and educate our children. These technical and societal changes are driving a decline of trust in institutions that no longer enjoy a monopoly on public information. They are also driving increased demand for flexibility to determine when, where, and with whom teaching and learning happen. Public education has begun to adopt a paradigm more aligned to 21st century demands, which include parents gaining more power to decide how their children learn.

Government’s changing role

Government’s role in public education will be impacted by a new public education paradigm that reflects these ongoing technical and cultural changes. Under the second paradigm, government had a near-monopoly in the public education market. This quasi-monopoly undermined public education’s effectiveness and efficiency because it failed to take full advantage of the knowledge, skills and creativity of students, families and educators.

In public education’s third era, government will regulate health and safety and help facilitate support services for families and educators but will no longer be the dominant provider of publicly-funded instruction. This regulatory and support function is like the role government currently plays in the food, housing, health care, and transportation markets. Most of the responsibility for how children are educated will shift from government to families and the instructional providers families hire with their children’s public education dollars.

Shifting government’s primary role from instructional monopoly to market regulator and supporter will require operational changes. Families will be able to choose from a plethora of instructional options and will need access to information that allows them to make informed decisions, as well as education advisers who can help them evaluate their child’s needs and develop and implement customized education plans to meet these needs. Government will need to ensure data accuracy and truth in labeling – much as it currently ensures food labels accurately describe what’s in the package.

Third paradigm issues

Providing each child with a high-quality customized education through a more effective and efficient public education market will require public education’s stakeholders to rethink all aspects of how it operates. Here are some issues we will need to address.

Public education’s third paradigm has old roots

In 1791, Thomas Paine proposed an ESA-type program for lower-income children in “The Rights of Man.”

“Public schools do not answer the general purpose of the poor. They are chiefly in corporation towns, from which the country towns and villages are excluded; or if admitted, the distance occasions a great loss of time. Education, to be useful to the poor, should be on the spot; and the best method, I believe, to accomplish this, is to enable the parents to pay the [sic] expence themselves.”

Paine’s recommended funding method was, “To allow for each of those children ten shillings a year for the expence of schooling, for six years each, which will give them six months schooling each year, and half a crown a year for paper and spelling books.”

Over 150 years after Paine’s proposal, Milton Friedman proposed a similar but more comprehensive plan in 1955. Many of the third paradigm’s core ideas existed in the 1700s prior to the industrial revolution. But they were not technically or politically feasible.

Thanks to modern technology and a growing acceptance of families’ rights to direct their children’s education, these ideas are viable today. We can now provide every student with an effective and efficient customized public education. While all students will benefit from customized instruction in a more effective and efficient public education market, lower-income students will benefit the most because they have historically been the most underserved by the current government monopoly. Underserved groups always benefit greatly when the markets they rely on for essential goods and services are more effective and efficient.

Public education’s transition to its third paradigm is happening faster in Florida than in other states. Over 500,000 students using ESAs is rapidly improving Florida’s public education market. Floridians are seeing in real time the creation of a virtuous cycle between supply and demand. More families using ESAs is encouraging educators to create more innovative learning options, which in turn is causing even more families to use ESAs, which in turn is causing even more educators to create more learning options. These rapidly expanding options increase the probability that all students, but especially lower-income students, can find and access learning environments that best meet their needs.

Public education’s first paradigm shift took about 100 years to complete (1830-1930). This second transition began around 1975 and will likely also take about 100 years to complete nationally. Like all paradigm changes, this one is proving to be a long slog. But larger societal changes will help ensure this transition’s success.

Education choice critics often assert that allowing families to choose the best learning environments for their children undermines our civic culture. They say our democracy is strengthened when children are required to attend public common schools.

The idea of public common schools originated in the early-to-mid 1800s in response to increased emigration from Europe. A surge of Irish immigration into Massachusetts led that state’s Protestant-dominated government to create the nation’s first mandatory school attendance law in 1852. Horace Mann, Massachusetts’ first secretary of education, led the campaign to teach Irish Catholic children how to be good Protestants in government-run common schools.

The Catholic community in Massachusetts and elsewhere rebelled against the Protestants’ public common schools and began creating Catholic schools. This ongoing conflict came to a head in Oregon in 1922 when the state amended its constitution to require all children to attend public (i.e., Protestant) common schools. The Ku Klux Klan (KKK) helped lead the effort to pass this amendment.

An order of Catholic nuns sued to prevent their Catholic school from being closed and prevailed in a 1925 U.S. Supreme Court decision, Pierce v. Society of Sisters. This decision ended the public common schools movement as envisioned by Mann, the KKK, and others, but the common school myth endures.

An order of Catholic nuns sued to prevent their Catholic school from being closed and prevailed in a 1925 U.S. Supreme Court decision, Pierce v. Society of Sisters. This decision ended the public common schools movement as envisioned by Mann, the KKK, and others, but the common school myth endures.

Education choice opponents regularly assert that returning to the days of most children attending public common schools is the best way to improve our polarized civic culture. But those days never existed. Most U.S. children have never attended public common schools. For most of our history, Black and white children attended racially segregated schools. My high school was racially segregated until my junior year (1971-72), which is about 140 years after Mann helped launch the common schools movement. Neighborhood attendance zones cause public schools to be segregated by family income. Public magnet schools separate students by interests and aptitude, and academic tracking within schools segregates students by academic achievement levels.

The non-existence of mythical public common schools does not refute the criticism that education choice programs undermine our civic culture. Fortunately, a growing body of research does refute this criticism and suggests education choice programs help improve our civic culture.

Patrick Wolf is a distinguished professor at the University of Arkansas’ College of Education and Health Professions. Wolf and his research team recently reviewed 57 studies that examined the relationship between private school choice and the quality of civic engagement. These studies consistently showed that participating in private school choice is associated with higher levels of political tolerance, political knowledge, and community engagement. Wolf concluded that, “Private schooling is a boost, not a bane, to the vibrancy of our democratic republic. The benefits of private schooling in boosting political tolerance are especially vital, as we need to be able to disagree with others without being disagreeable.”

Charles Glenn is professor emeritus of educational leadership and policy studies at Boston University’s Wheelock College of Education & Human Development. Glenn conducted research that helps explain Wolf’s findings.

Glenn examined the role Islamic schools play in helping Muslim immigrant children assimilate into the U.S. culture. He found these children assimilated much better when they attended Islamic schools that help them maintain their religious and cultural identity while successfully adapting to American values and norms. Glenn concluded that these schools helped students develop a sense of belonging in both their cultural community and the wider U.S. community by focusing on cultural preservation and adaptation. This dual focus was apparently crucial to helping these Muslim children successfully integrate into U.S. society.

Glenn’s findings are similar to what we see students experiencing in the education choice programs Step Up For Students manages. Most of the students we have served over the past 23 years have come from lower-income and minority families. When we poll these families as to why they are participating in our programs, the top answer is always safety.

All people, but especially children, have a basic need to be physically and psychologically safe. Children who do not feel safe in school go into fight or flight mode, which shows up as them refusing to go to school or going to school and constantly getting into trouble.

Parents regularly report amazing transformations in their child’s behavior when they use education choice scholarships to enroll their troubled child in a school where this child feels safe. While parents often see these changes as miraculous, these improvements reflect normal human psychology. Most people’s behavior is better when they feel safe and secure.

This need for safety and security while participating in public education is why education choice programs help improve our civic culture. As Glenn’s research shows, education choice programs help families find environments in which their children learn to feel secure about who they are and learn to use this security as the basis to interact appropriately with those who are different from them.

Much of the polarization and hostility we see in our civic culture stems from people feeling unsafe and insecure. The immigrant Muslim children Glenn studied learned to feel secure about themselves and their native culture in private Islamic schools and used this security as the basis to interact successfully with our diverse society. They became secure and confident and saw cultural differences as opportunities to learn and grow, not as threats.

The evidence suggests that the choice critics are wrong. Education freedom does not contribute to unhealthy social discourse. When done well, it is part of the solution.

The magisterial "History of the Peloponnesian War" relates the calamity of conflict between the Greek city states of Athens and Sparta. The account includes an Athenian addressing the Spartan assembly before the outbreak of hostilities, making the case against a Spartan attack on Athens.

Bellicose Spartan allies had finished urging the Spartans to launch a war against Athens, but an Athenian invited to offer a response noted a compelling list of reasons why the Spartans should not launch a war. These included past Athenian victories over the Persians in two separate invasions of Greece, and a treaty requiring Athens and Sparta to resolve disputes by arbitration. The Athenian then predicted (correctly as events would later prove) that even if Sparta defeated Athens and took over the Athenian empire, Sparta would quickly lose control of it. Finally, the Athenian concluded:

Take time then in forming your resolution, as the matter is of great importance; and do not be persuaded by the opinions and complaints of others to bring trouble on yourselves, but consider the vast influence of accident in war, before you are engaged in it. As it continues, it generally becomes an affair of chances, chances from which neither of us is exempt, and whose event we must risk in the dark.

Unfortunately, the Spartans failed to heed this wise counsel and plunged Greece into the unimaginable horrors of a 27-year internecine war. Americans of various camps today would do well to consider the vast influence of accident in war, as far too many seem to march off to internecine conflict.

Corey Comperatore was shot and killed while sheltering his family from gunshots during the attempted assassination of former President Donald Trump. Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro gave moving remarks about the loss of Comperatore and the need for the use of peaceful processes to resolve political disputes. In his remarks, Shapiro echoes the urging of the Athenian addressing the Spartans:

Political disagreements can never, ever be addressed through violence. Disagreements are okay, but we need to use the peaceful political process to settle those differences. This is a moment where all leaders have a responsibility to speak and act with moral clarity.

To which I can only thank Gov. Shapiro for his leadership and further say: Amen.

It wasn’t just Donald Trump who narrowly dodged a bullet; it may have been the nation as a whole. The past few years saw an assassination attempt on a group of Congressmen, a sitting Supreme Court justice, and now on one of the major party nominees.

I invite you, dear reader, to consider for a moment just how badly things might have unraveled if the bullet that grazed Trump’s ear had slain the former president. We live in a diverse and sadly polarized society. Gov. Shapiro of course is entirely correct that we can and should use democracy to settle our disputes. The Spartans should have honored their treaty obligation to resolve disputes through arbitration. They chose not to, and it brought a golden age of Greek civilization crashing into chaos, death and ruin.

No faction in our society should imagine anything good coming of a normalization of political violence. I know people who have spent decades trying to ban personal firearms, and I know other people who have spent decades collecting personal firearms. In an escalation of political violence of the sort that very well may have narrowly dodged, my only prediction: calamity. Consider again the quote:

Take time then in forming your resolution, as the matter is of great importance; and do not be persuaded by the opinions and complaints of others to bring trouble on yourselves, but consider the vast influence of accident in war, before you are engaged in it. As it continues, it generally becomes an affair of chances, chances from which neither of us is exempt, and whose event we must risk in the dark.

Tolkien’s Gandalf gave similar advice:

Practical steps such as an increased role for federalism, a reassertion of Congressional authority and a stronger commitment to pluralism could all help. An embrace of pluralism in education is a vital part of moving away from a zero-sum society. The nation’s founders never intended an imperial federal executive trending towards apocalyptic winner-takes-all presidential elections. More urgently and immediately, however, the country needs far more leadership like that provided by Josh Shapiro at the press conference linked to above.

We got a huge bit of good luck with the narrow failure of this assassination. Let’s consider carefully how we might depend less on the vast influence of accident, even relatively happy ones, and more upon wisdom and virtue.

Five member universities departed the Pacific-12 Conference last week, following the leads of three others. Despite boasting more NCAA national championships than any other league, the “Conference of Champions” as we knew it died. I anxiously await a modern Edward Gibbon to document the fall of this part of American life. While we naturally regret the fall of valued institutions, we have cause to fear efforts to prop up failed institutions even more.

As an Arizonan, I know many who feel an acute sadness to see the Pacific-12 go. The Pacific-12 Conference participated in cherished traditions such as the Rose Bowl and the Rose Bowl Parade. College football has slowly but steadily shifted from being a quaint but delightful regional pastime into professionalization. Many, including your author, find this unsettling. The Conference of Champions was a cherished part of life in the American West but died through partition.

We should, however, understand change as being inevitable, and stasis as dangerous. The amateur model eventually collapsed under the crushing weight of hypocrisy. Universities made hundreds of millions of dollars while enforcing “amateurism” on athletes. Professional profits for me, amateurism for thee was only going to last so long. Sure enough an (appropriate) assertion of individual rights by athletes in court set athletic departments scrambling for the resources to compensate players, accelerating a trend towards consolidation.

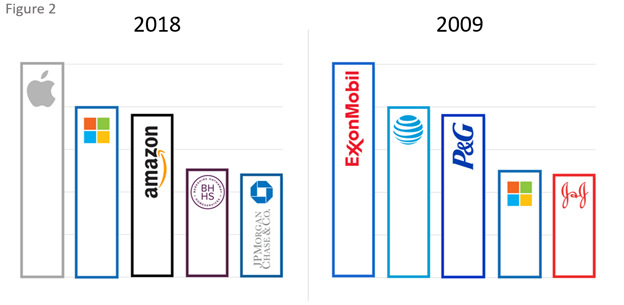

Constant change is also a feature, not a bug, of American industry. The S&P 500 is an index of large American publicly traded corporations. On average there are 22 changes in the index annually. This means that half of the companies in today’s S&P 500 index were not in the index 20 years ago. Companies drop out for a variety of reasons: bankruptcy, mergers or simple decline. Growing, upstart companies move into the index as others fall out. Even the apex companies are not immune. For instance, none of the top five S&P 500 companies from 2009 was still in the top five in 2018.

We can see the danger of stasis in America’s K-12 system. Americans regret the closing of a public school as we in the West feel about the loss of the PAC-12. If, however, we allow antiquated institutions to linger despite an established inability to deliver, we pit our sentimentality against our flourishing. The failed K-12 status quo traps teachers in dysfunctional bureaucratic systems and shortchanges students while creating an ever-growing financial burden on society.

The beneficiaries of today’s high-cost but low performing K-12 system have largely configured the K-12 system to their interests. They have effectively organized themselves for political action and fiercely resist change. They use our sentimentality to maintain stasis. The best method for managing the very real tension between our desire for freedom and progress and our desire for stability and tradition lies in voluntary associations. In K-12 this means giving teachers and families the opportunity to supply and demand schools and allowing voluntary associations to decide which thrive and which close.

We currently leave to politics the task of deciding which schools replicate and close. The PAC-12 demonstrated a regrettable level of dysfunction in the years leading to the dissolution, but it operated as a well-oiled machine in comparison to many American school districts.

An ongoing voting with feet can decide which institutions we value enough to preserve, and which should go the way of a delisted company or (alas) the Conference of Champions. While we honor tradition, eternal life is not ours to grant our institutions, and a great folly lies in attempting to grant it. We should empower families, not bureaucrats, to resolve the tension between tradition and progress.

Editor’s note: This opinion piece, written by Step Up For Students’ director of policy and public affairs, appeared April 19 on the Florida Politics blog. The commentary was submitted as a rebuttal to an editorial in the Palm Beach Post, which declined to publish it.

Florida’s public education system is leaps and bounds better today than the national embarrassment it was 20 years ago.

But critics triggered by “school choice” continue to suggest, without a scrap of proof, that our schools are basket cases, and choice is to blame.

In its April 7 editorial, the Palm Beach Post perpetuates long-running myths and hides inconvenient facts in condemning a proposed new choice scholarship. Its conspiracy theory is a doozy: “Vouchers” are draining money from public schools, in violation of the Florida Constitution, and while our public schools are being decimated, privateers are cashing in.

The new scholarship would end a waitlist of 13,000 for the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship, which serves 100,000 lower-income students. The value of the new scholarship would be akin to the existing one, yet the Post concludes it “robs Florida’s public schools of needed money.”

No, it doesn’t.

The tax credit scholarship is worth 59 percent of per-pupil spending in district schools. That’s why every independent fiscal impact analysis of the program — eight to date — has concluded it saves taxpayer money that can be reinvested in public schools.

The drain on public schools would come if the program ended.

Construction costs alone would surge into the billions if private school students flooded into public schools. If teachers thought getting a decent raise was tough now, imagine the difficulty with massive new strains on government coffers.

The misinformation and oddities don’t end there.

The editorial suggests private schools are run amok with for-profits when in reality the vast majority are tiny nonprofits. If the paper’s main beef is Florida public schools are being fed crumbs — it calls the state’s low rankings on education funding “pathetic” — how could tiny nonprofits “grab a healthy haul” with 59 percent of “pathetic?”

The editorial also gives credence to the insights of the Florida teachers union, which is rich.

In 2017, the Florida Supreme Court dismissed the union-led lawsuit to kill the tax credit scholarship because the union couldn’t provide a microfiber of evidence to back its claims of harm to public schools.

That hasn’t stopped the union from continuing to flood the public arena with the same erroneous claims.

The Post is right about one thing: accountability is different for public and private schools. Private schools aren’t subjected to the same level of regulation as public schools because they also face the accountability that comes when parents have power to choose.

Parents dissatisfied with private schools can leave, at any time. That’s not true for many parents in public schools, particularly low-income parents.

Unlike parents of means, they can’t just up and move to neighborhoods where they’re guaranteed spots in high-performing schools.

Finding the balance between regulations and choice isn’t easy. But the evidence to date suggests we’re on the right track. Standardized test scores show tax credit scholarship students were typically the lowest-performing students in their prior public schools.

But now, according to a new Urban Institute study, they’re up to 43 percent more likely than their public-school peers to attend four-year colleges, and up to 20 percent more likely to earn bachelor’s degrees.

That success is not coming at the expense of public schools. Florida’s graduation rate was 52 percent 20 years ago. It’s 86 percent now. Florida is now No. 3 in the nation in percentage of graduating seniors who’ve passed Advanced Placement exams; No. 4 in K-12 Achievement, according to Education Week; No. 1, 1, 3, and 8 on the four core tests of the National Assessment of Educational Progress, once adjusted for demographics.

These rankings aren’t “moribund.” They’re encouraging.

There’s no good reason why the steady progress of our public schools is routinely ignored. Or why choice programs are selectively scrutinized. Florida has been spending billions of taxpayer dollars on tuition for private and faith-based schools for years — for multiple scholarships in higher education, preschool and K-12. If the proposed new scholarship is “an abuse of the Florida Constitution,” wouldn’t they all be?

Why do critics obsessively single out the choice scholarships that are designed to help low-income families? And shrug at the rest?

Public education in Florida has big challenges, and adequate funding is one of many.

But emotional arguments detached from basic facts don’t advance the hard conversations we need to have.

Jack Coons of Berkeley Law writes that it's time we all grasp that what we have called "public education" is actually anything but - and it's long time to make it so through school choice.

In much of American society, children attend a school that has been chosen by their parents. Mom and Dad have picked out a home in the attendance area of a certain school that is owned and run by the government. At the very least, when they moved they knew its reputation. Whether or not the school was a major consideration, they accepted it as a substantial part of the culture that would count greatly in shaping their child’s worldview.

That school of theirs will be called “public.” My Webster’s defines this word in various ways, but most prominent among these meanings, and consistent with all, is this one: “Open to all persons.”

Think about it. Is that government school that you chose for your child open to all children? Of course it is, with one condition – namely that every American family can afford to live where you have chosen to live. Is this public?

Of course, your chance of location in this “public” school attendance area may have had little to do with your finding that dream home. You may be able to afford a private school, and that is your choice now. It may be Saint Mary’s or the Free Thought School, but it is there for the picking, and you pick it. Now my question: Is this private school any less public than the Eleanor Roosevelt Elementary in your attendance area? (more…)

Today is back-to-school day for most school districts in Florida. But for the Plucinski family of Central Florida, it’s back to schools. And not just district schools.

Sisters Cora and Zuri will board a school bus to start the day at a district elementary school, while mom Corin Plucinski will drive brothers Zach and Nathan 30 minutes to a private school. They attend with help from one of Florida’s multiple educational choice scholarships.

In many parts of the country, this may be unusual. But in Florida, which offers one of the robust arrays of school choice in the country, it’s increasingly common. Growing numbers of families have different children attending different schools in different educational sectors.

To the Plucinskis, whose oldest is now headed to college after graduating from a district high school, there’s nothing odd about it.

“When you’ve got five kids you’re always juggling something anyway,” Corin Plucinski said.

Thirty years ago, roughly 90 percent of Florida students in preK-12 attended assigned district schools, and about 10 percent attended private schools. Beyond a handful of magnet schools, there was no state-supported school choice.

Fast forward a generation. Today, 46 percent of Florida students – 1.7 million – attend something other than their assigned district schools. About 300,000 attend charter schools. Another 300,000 attend private schools. Most of the rest attend options created by school districts, from magnet schools and career academies to IB and dual enrollment programs.

This flourishing landscape gives parents more opportunities to find the right fit for their kids. And for many families, that means one child in this sector, another in that sector. (more…)

William N. Sheats was, in many ways, the father of Florida's public school system. He was also an ardent racist who declared war on a racially integrated private school in North Florida, which he referred to as a "nest of vile fanatics" in an episode that subjected the state to national ridicule.

But perhaps the most fascinating — and troubling — aspect of this complicated figure is this: By the standards of his time, he was a moderate.

Several times during his long run as the leader of Florida's public education system, he faced threats to his political career because, in the view of his opponents, he wasn't racist enough.

Sheats was Florida's first elected education superintendent, serving from 1893 to 1904, and again 1913 until his death in 1922. He worked to modernize Florida's uniform system of public schools and helped draft the first statewide curriculum. He reformed teacher training and certification, requiring educators to pass exams to prove subject-area mastery. He worked to ensure more public high schools were accredited, and helped pass the state's compulsory-attendance law in 1919. During his tenure, Florida had one of the best-funded public school systems among southern states and had more accredited high schools per capita than any other state in the region.

But Sheats was also a racist. He once declared access to education would "make the vast number of idle, absolutely worthless negroes industrious and self-supporting." (more…)

Editor's note: This op-ed by Step Up For Students President Doug Tuthill was written in response to a March 10 column by Palm Beach Post columnist Frank Cerabino. The Post published it online last night.

The new world of customized public education is not a zero-sum game. A student who chooses an International Baccalaureate program is not hurting a student who picks a career academy. A student in a magnet school is not undermining students in her neighborhood school. We need to offer children different options because they learn in different ways.

Sixty-thousand of Florida’s poorest schoolchildren chose a private school this year with the help of a scholarship, and this 12-year-old program strengthens public education by expanding opportunity.

The program, called the Tax Credit Scholarship, is one learning option for low-income students who face the toughest obstacles, and is part of an expanding universe of educational choices that last year served 1.5 million — or 42 of every 100 — Florida students in PreK-12. Those who suggest scholarships for low-income children harm public education are wrong. These scholarships and the opportunities they provide strengthen public education.

The state’s covenant is to children, not institutions, and these low-income students are being given options their families could not otherwise afford. That their chosen schools are not run by school districts makes them no different than charter schools or McKay Scholarship schools or university lab schools or online courses or dual college enrollment. That the state supports these scholarships is no different than the state paying for these same students to attend a district school. These scholarships are publicly funded, publicly regulated, public education.

Why, then, would a Palm Beach Post columnist suggest that scholarships for low-income children come “at the expense of public education”?

Independent groups and state agencies have repeatedly concluded that these scholarships, worth $4,880 this year, actually save the state money. The most recent projection came from the Consensus Revenue Estimating Conference, which placed the savings last year at $57.9 million. While it is regrettably true that district, charter and virtual schools have suffered financial cutbacks in recent years, they were not caused by these scholarships. In fact, this scholarship program was impacted by those same cuts.

The bill the Legislature is considering this year helps reduce the waiting list for this scholarship, so it is important to know who it serves. On average, the scholarship students live only 9 percent above poverty, more than two-thirds are black or Hispanic, and more than half come from single-parent homes. State research also shows they were also the lowest performers in the public schools they left behind.

These students are required to take a nationally norm-referenced test yearly, and the encouraging news is that they have been achieving the same gains in reading and math as students of all income levels nationally.

The new world of customized public education is not a zero-sum game. (more…)

Education is a complex and nuanced issue, and advocates on all sides need to be mindful not to overreach. Supporters of school choice sometimes overpromise the benefits of vouchers and tax-credit scholarships, leaving them open to attack. On the other side, school choice critics sometimes appeal to a mythical concept of the common/public school that never really existed.

Edward B. Fiske, a former New York Times education editor, and Helen F. Ladd, a professor at Duke University, demonstrate exactly this in a recent op-ed in the News & Observer. Fiske and Ladd keep their arguments simple: school choice is unconstitutional because it “destroys” the state’s ability to provide a free uniform system of education that is, as they say, “accessible to all students.”

Their argument may sound reasonable to a school choice critic, but the reasoning is grounded in mythology. Understanding this mythology exposes the underlying contradictions with the opposition to school choice.

First, it is a myth that common/public schools are open to every student. Students are assigned to schools and those schools are free to reject any student not within the school zone.

As Slate columnist Mathew Yglesias recently noted, the word “public” in public school really only means the school is government-owned and operated. He correctly observes that “a public school is by no means a school that's open to the public in the sense that anyone can go there.”

Yglesias isn’t a school choice fanatic but he isn’t blind to the results of a zone-based attendance policy. The result turns neighborhood schools into a “system of exclusion.” (more…)