“That which purifies us is trial, and

“That which purifies us is trial, and

trial is by what is contrary.”

John Milton, Areopagitica

My thanks to those eminent school choice advocates Larry Sand of California and collaborators Robert Enlow and Jason Bedrick of EdChoice in Indiana. I recommend reading their recent critiques here and here of the design of those half-dozen model statutes for choice that Stephen Sugarman and I pumped out from the 1960s until the 21st century.

These critics worry that our models are too complex, hence, self-defeating at the polls or in the legislature; and they fret even more that we are focused principally upon lower-income parents.

For them, the structure must be simple, as Milton Friedman imagined it, with equal subsidy for every child of every family in the same grade and with little or no regulation of private school admission policy or recruitment strategies.

Sugarman and I make them unhappy, because we would have participating schools set aside their unchosen applications for a final random selection of a fraction of its entries, giving the unchosen child of the poor a chance at subsidized admission. We would also require the school to make itself known in the open market, trying thereby to assure that lower-income parents have the chance to learn what their new responsibility requires in the way of sophistication about their options.

Our critics recognize the suffering of the lower-income family under the status quo, but they insist that this problem is best addressed by a Friedman-blessed system of subsidy that includes all parents, even those who least need it. It is this alone, they believe, that will bring the civic liberation of the poor.

They are best, also we hear, because this pure system which they favor is politically the most saleable; any focus upon the poor is unpopular.

I must have overlooked some such rousing success of the pure market approach in capturing the voting hearts of our 50 state electorates. For many years, the Friedman folks in many states have been running ballot initiatives for universal vouchers. Their level of success is unimpressive.

Still, this issue of the universality of any system of subsidized choice seems to me the lesser of two central questions.

So, let us try another plebiscite offering vouchers to the rich and poor alike. The core dispute will then be the nature and extent of state government regulation of participating schools.

Sugarman and I have long felt concern over such matters as admission policy advertising (targeted or universal), procedural rules for expulsion and so on. At least in the short run, parents who have never chosen will need to acquire some of the sophistications of the middle class.

I can understand how pure market minds could continue to draw the line at certain forms and degree of regulation; so would I. But, just maybe, they could help to make it “efficient” in the way least intrusive of the participating private school. What puzzles me is their reluctance even to consider how the untutored parental mind needs help to become a wise consumer and how the seller must rescue such mothers and fathers with simple information about just who and what this particular school is.

Most important, if a school participates, it should be ready at the end of the admission process to take a few children – say 15% – at random, children whom they had not already picked from among their applicant pool. In short, it has seemed fair and rational to ask the seller to undertake a wee bit of “social integration.”

Finally, and most important, we should ask these pure market folks ever to keep in mind that decisions about design will be made by 50 individual state governments. Might it not be to our civic good as a nation to watch and learn from the experience of those states with a variety of statutory models just what is popular and what works?

Editor’s note: Robert Enlow, president and CEO of EdChoice, and Jason Bedrick, director of policy at EdChoice, provided the following response to a post from redefinED columnist John Coons.

In a recent redefinED blog post, school choice icon John Coons proposed finding common ground between two groups of education reformers whom he calls the “Miltonites” or “marketeers” (supporters of a free-market approach to educational choice with universal eligibility in the mold of Milton Friedman) and the “voucher left” (those, like Coons, whose primary concern is improving the well-being of the poor). His point is that what unites the two groups is much more—and more important—than what divides them, so they should find ways to work together as “happy co-conspirators” to advance educational choice.

As two staunch Miltonites, we couldn’t agree more.

Advancing choice and opportunity requires a broad and ideologically diverse coalition, as when the Republican governor of Wisconsin, Tommy Thompson, worked with Democratic legislator Polly Williams to enact the first voucher program of the modern era. More recently we’ve also seen a largely successful coalition of staunch conservatives and ardent liberals working together to advance criminal justice reform.

As with any diverse coalition, however, there is bound to be some healthy disagreement, particularly over the means to achieve shared ends. In the choice coalition, the fault lines have often been over access (universal vs. targeted) and regulations (libertarian vs. equalitarian).

First, the common ground. As with many on the social justice wing of the school choice movement in recent years, Coons now appears ready to support Miltonite universal access—so long as the financial support for the disadvantaged is greater. On this front, today’s Miltonites are already pretty much in agreement in principle though there may be some disagreement over the details.

When it comes to regulations, however, the differences over means are more profound. While well-intended, the regulations Coons proposes are likely to stymie the ability of choice programs to benefit the very people Coons wants to help the most. Instead, we propose that Miltonite means are best to achieve Coonian ends.

Universal Choice

Whereas in the past, Coons and Friedman ran dueling proposals that differed sharply over eligibility, now Coons proposes a universal approach in which “at least a trophy amount to the well-off in recognition of their civic role as parent, while awarding the poor the full economic reality of that same parental responsibility and authority.” It’s not clear what a “trophy amount” means in practice, but while we think it is important that everyone receive a substantial scholarship, we support giving additional aid to disadvantaged populations, such as students with special needs, English Language Learners, and children from low-income families.

Universality is essential for both policy, political, and personal reasons. In terms of policy, targeted choice programs may fill empty seats in existing schools, but only the widespread availability of educational choice will lead to the systemic transformative change that our K-12 system needs.

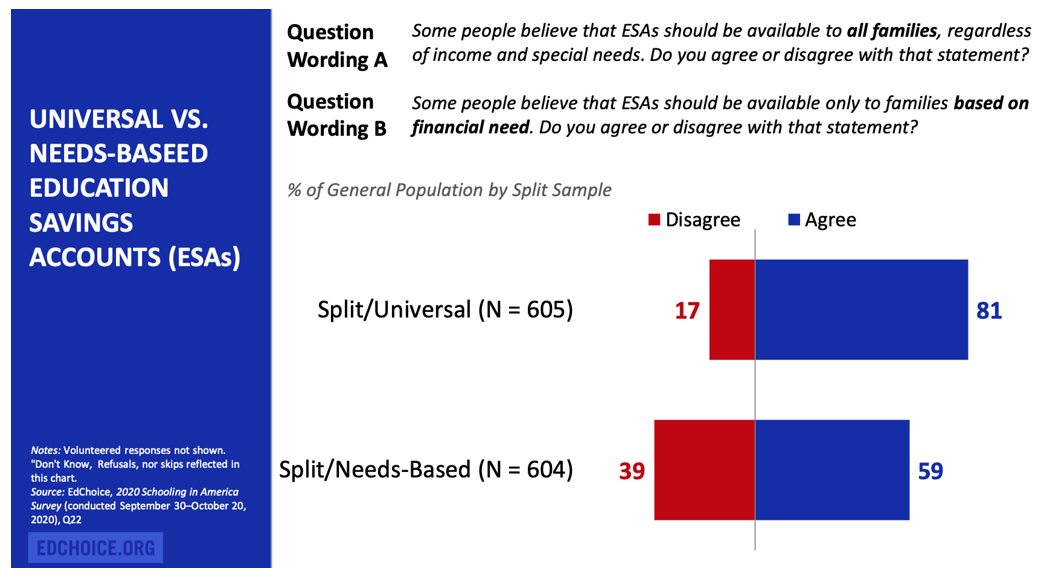

Universality is also more politically sustainable. There is significantly higher public support for universal programs than targeted ones. EdChoice’s latest Schooling in America Survey found that 81 percent of Americans support universal choice policies while only 17 percent oppose them. By contrast, only 59 percent supported making choice programs available based on financial need while 39 percent opposed doing so.

Moreover, as Milton Friedman often observed, “Programs for the poor are poor programs.” Welfare is often on the chopping block, but Social Security never is. Likewise, programs that serve upper-middle-income families who have political capital tend to be better-run than those that serve only the poor. One need look no further than the district schools serving well-off families compared to those that serve lower-income families. The poor are best served by being in the same boat as the more advantaged.

On the personal level, low-income families don’t want to feel like or be seen as charity cases. Families who send their children to a public school are receiving a government subsidy, but they don’t feel like a charity case because everyone gets access. No wonder then that our recent poll found significantly higher support for universal choice among low-income families. Among respondents earning less than $40,000 annually, 92 percent supported universal access while only 66 percent supported means-testing.

As we noted above, we support giving additional aid to disadvantaged families, but we should be clear-eyed about the tradeoffs and wary of pitfalls. Families who must prove their income face additional barriers, including intrusive questions and a significant amount of paperwork. Also, we must be careful that we don’t create a poverty trap that takes away benefits as a household’s income rises. Educational choice programs should assist low-income families by expanding opportunity but should not ever be designed in such a way as to create a disincentive for families to improve their financial situation.

Ultimately, universal access to educational choice is about erasing the invisible but all-too-real lines that divide our nation’s education system into haves and have-nots. A Friedman noted in Free to Choose:

The tragedy, and irony, is that a system dedicated to enabling all children to acquire a common language and the values of U.S. citizenship, to giving all children equal educational opportunity, should in practice exacerbate the stratification of society and provide highly unequal educational opportunity.

Ending this stratification—ending the lines between us all and creating opportunity for all especially the most vulnerable—is the true goal of the Miltonite view of educational opportunity.

The Role of the Market

A well-functioning market is necessary to provide families with a diverse array of educational options and to spur systemic innovation and improvement. Coons is open to the importance of the market to educational choice but takes Friedman to task for taking a “let the market rip” approach, claiming:

It was to [Friedman] an economic sin to favor lower-income families in either the amount of the subsidy or the design of regulation for participating schools. The focus for him was not on the role of the parent, but rather the achievement of simplicity and laissez-faire in the economy.

This does not do justice to Friedman’s views, which were considerably more nuanced.

What Coons calls Friedman’s “let it rip” approach is really Friedman’s sincere belief in parents and their ability to choose. As Friedman wrote in Free to Choose:

Parents generally have both greater interest in their children’s schooling and more intimate knowledge of their capacities and needs than anyone else. Social reformers, and educational reformers in particular, often self-righteously take for granted that parents, especially those who are poor and have little education themselves, have little interest in their children’s education and no competence to choose for them. That is a gratuitous insult. Such parents have frequently had limited opportunity to choose. However, U.S. history has amply demonstrated that, given the opportunity, they have often been willing to sacrifice a great deal, and have done so wisely, for their children’s welfare.

Moreover, Friedman’s opposition to certain regulations stemmed not from a sense that they were a “sin” against a free-market religion but rather from his empirical studies of how markets work and how certain well-intended regulations can have unintended consequences.

As Friedman himself wrote in the Wall Street Journal in 2000:

I have nothing but good things to say about voucher programs, like those in Milwaukee and Cleveland, that are limited to a small number of low-income participants. They greatly benefit the limited number of students who receive vouchers, enable fuller use to be made of existing excellent private schools, and provide a useful stimulus to government schools. They also demonstrate the inefficiency of government schools by providing a superior education at less than half the per-pupil cost.

But such programs are on too small a scale, and impose too many limits, to encourage the entry of innovative schools or modes of teaching. The major objective of educational vouchers is much more ambitious. It is to drag education out of the 19th century – where it has been mired for far too long – and into the 21st century, by introducing competition on a broad scale. Free market competition can do for education what it has done already for other areas, such as agriculture, transportation, power, communication and, most recently, computers and the Internet. Only a truly competitive educational industry can empower the ultimate consumers of educational services – parents and their children.

Coons claims that the Miltonites have “succeeded largely in giving subsidized parental choice the image of Friedman himself,” meaning universal programs that have “nearly zero regulation of the chosen providers.” In reality, the Miltonites have been all too willing to settle for small, targeted programs that often come with regulations that undermine their effectiveness.

As we highlighted in a recent essay for the American Enterprise Institute, markets are essential for creating a feedback loop that organically expands options and improves quality over time. In the words of AEI’s Yuval Levin, markets enable the channeling of “social knowledge from the bottom up” rather than “impos[ing] technical knowledge from the top down” via a Hayekian three-step process of “experimentation, evaluation, and evolution.”

Markets are ideally suited to following these steps. They offer entrepreneurs and businesses a huge incentive to try new ways of doing things (experimentation); the people directly affected decide which ways they like best (evaluation); and those consumer responses inform which ways are kept and which are left behind (evolution).

This three-step process is at work well beyond the bounds of explicitly economic activity. It is how our culture learns and evolves, how norms and habits form, and how society as a general matter “decides” what to keep and what to change. It is an exceedingly effective way to balance stability with improvement, continuity with alteration, tradition with dynamism. It involves conservation of the core with experimentation at the margins to attain the best of both.

Policymakers should be careful to avoid policies that unduly interfere with this process. As Jason Bedrick and Lindsey Burke explained in greater length in chapter nine of School Choice Myths, some of Coons’ proposed regulations have unintended consequences that undermine the ability of choice programs to aid the very people they’re intended to help. For example, as Bedrick and Burke explain, such open-admissions requirements can restrict the diversity of options available to scholarship students:

Open-admissions mandates prevent families from using vouchers at schools with certain missions or those that are oriented around voluntary communities, such as religiously affiliated schools or single sex schools. They also discourage participation among schools that are designed to serve certain types of students, whether the academically gifted, students with particular special needs, or those with a penchant for STEM or drama and the arts.

College voucher programs, like Pell Grants, are publicly funded without imposing open-admissions requirements out of a recognition that the purpose of the public funding is to expand educational opportunities for students to enroll in the learning environments that are the right fit for them. That requires a diversity of options, including schools that are geared toward particular student populations or that have particular missions or religious affiliations.

Such regulations can also affect the quality of available options. Louisiana’s voucher program is the most regulated in the country, imposing open admissions, the state test, and price controls to guarantee low-income families access to high-quality schools. What happened is that most private schools refused to participate, and Louisiana’s voucher program became the first in the nation to produce negative effects in a random-assignment study.

How did that happen?

Well-intentioned regulations are the likely culprit. In a survey by the American Enterprise Institute, three out of four Louisiana private school leaders who opted not to have their school accept voucher students cited concerns about the effects of the open-admissions requirement. As Bedrick and Burke explained, there were important differences between the participating and non-participating schools:

These concerns [about regulations] appear to have dissuaded many of the higher-performing schools from accepting [Louisiana Scholarship Program (LSP)] students, so participating schools were of lower quality, on average. One of the initial LSP studies contained some suggestive evidence of this. In the decade before the LSP was expanded statewide, the non-participating schools experienced modest enrollment growth (about 3 percent, on average). By contrast, over the same period, the participating schools experienced a significant decline in enrollment (about 13 percent, on average). In other words, private schools that had been able to attract students before the LSP expansion tended to reject the vouchers, while voucher-accepting schools tended to be those where enrollment had been falling.

These concerns are not confined to Louisiana. Another multi-state study found that admissions mandates significantly reduced the likelihood that private schools would participate in a potential school choice program. The number of private school principals who were “certain to participate” in a school choice program dropped by around 17 to 21 percentage points, or 70 to 84 percent, if the program had an admissions mandate.

By contrast, Florida eschews admissions mandates and other Louisiana-style regulations yet more than 130,000 low-income students are now attending the schools of their families’ choice. Moreover, far from “creaming,” studies show that Florida private schools are admitting scholarship students who were lower-performing, on average, than their demographic peers before receiving a scholarship. In other words, as Louisiana and Florida show, open-admissions mandates are neither necessary nor sufficient to expand access for lower-income families—and may even have the opposite effect.

Better Together

Miltonites and Coonians are united in a shared desire to improve the lot of “the least among us.” We should also share a commitment to learning from what has and hasn’t worked. The past three decades of experience with educational choice show that Miltonite means are the surest path to achieving Coonian ends.

Robert C. Enlow at Ed Choice crunched some numbers on how things might look if 10 percent to 30 percent of private school students migrate to public schools this fall. The state-by-state analysis is not an unimaginable scenario, given our suddenly massive unemployment rate – one in five American workers currently are out of work.

Robert C. Enlow at Ed Choice crunched some numbers on how things might look if 10 percent to 30 percent of private school students migrate to public schools this fall. The state-by-state analysis is not an unimaginable scenario, given our suddenly massive unemployment rate – one in five American workers currently are out of work.

Enlow points out what might happen if private school students can no longer attend those schools due either to their families’ financial hardships or due to drops in charitable giving that supports scholarships for students in need.

Click on this link and you’ll see that Florida is the fifth state from the top of the chart. The 10 percent scenario would cost the state an additional $161.5 million; the 30 percent scenario would precipitate a drift closer to half a billion in added costs.

The total state and local cost scenarios for Florida are $363 million and $1.1 billion for the 10 percent and 30 percent scenarios, respectively.

I use the term “added costs” rather than “increased revenue” because it is easy to estimate even from a distant patch of cactus that Florida is unlikely to have a lot of extra cash available next fall. Even if there were a spare billion dollars available, hospitals are in terrible shape (they make most of their money from elective procedures), universities around the country have begun closing and/or furloughing staff, and there is no telling what other calamities await.

Could K-12 enrollment go up and state funding go down? It’s hard to rule anything out in a world where oil producers pay people to carry away oil at a negative price.

Nationally, the 30 percent scenario looks like $10 billion in added costs at a time when state budgets will be under fantastic strain with a great many competing demands for funds. So public schools could get lots of new students and budget cuts at the same time if this goes poorly.

So, to our friends out there with lamentably traditional K-12 policy preferences, please be careful what you wish for – you might just get it.

This week, we posed that question to many of you on Twitter and got an amazing response: more than 1,000 tweets!

This week, we posed that question to many of you on Twitter and got an amazing response: more than 1,000 tweets!

In the meantime, we also posed it to some stalwarts in the school choice movement, and asked them to write a short blog post in response. Next week, we’ll begin publishing their fun, thoughtful and provocative answers.

Here’s the all-star line-up:

Monday, Dec. 23: Jon Hage, founder and CEO of Charter Schools USA.

Tuesday, Dec. 24: Robert Enlow, president and CEO of the Friedman Foundation for Educational Choice.

Thursday, Dec. 26: Joe McTighe, executive director of the Council for American Private Education

Friday, Dec. 27: Dr. Howard Fuller, board chair, Black Alliance for Educational Options

Monday, Dec. 30: Julio Fuentes, president and CEO, Hispanic Council for Reform and Educational Options

Tuesday, Dec. 31: Peter Hanley, executive director, American Center for School Choice

We hope you enjoy the posts as much as the #schoolchoiceWISH event. It was a hit! (more…)

The question of how to hold private schools academically accountable for publicly supported, school voucher students remains contentious and, frankly, unclear. But to oppose tests out of fear the opposition will twist the results is simply untenable.

In one of the latest venues where this debate played out, at the American Federation For Children policy summit this week on the banks of the Potomac River, part of the audience broke into applause when Bob Smith, the former president of Messmer Catholic Schools in Milwaukee, pushed back on testing. Smith and Messmer schools are both highly regarded, and he was not coy about his rationale.

“We have some enemies who have sworn they are going to destroy this program, beginning with two presidents of the United States, and a number of secretaries of education,” Smith said. “Until those people stand up, and with the same fervor, deny that they will use that data against private schools, I will not trust them.”

At least two of the panels during the two-day event revealed the ongoing split over how, or even whether, to test students on school vouchers and tax credit scholarships.

Not surprisingly, Robert Enlow, president of the Friedman Foundation For Educational Choice, made an eloquent and principled case for why the marketplace itself is a powerful force for assuring quality. Parents whose students are on scholarships, just like parents whose students are on private tuition, can and do walk away from schools that aren’t serving their needs – in some case putting schools out of business in the process.

Adam Emerson, director of parental choice for the Fordham Institute, made the principled case for why public is different. Public schools are under enormous pressure to produce results on state tests, with sometimes severe consequences for failure. To expect private schools serving publicly supported students to be immune from that system is unrealistic. It also denies elected policymakers who are paying the bill a test that they view as an important report card.

One slice of the divide that was hard to ignore was the contributions of the only current school administrator to serve on either panel. (more…)

Oh how the blog gods have smiled down upon redefinED.

The 2012 Republican National Convention will be held in downtown Tampa this month – six blocks from the building that houses Step Up for Students and our humble blog. I received press credentials to cover the convention. And next week, as a lead-up to the event, we’ll be posting essays from some of the leading voices in school choice and education reform.

Here’s the line up: former U.S. Secretary of Education Margaret Spellings; Chester E. Finn, Jr., president of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute; Robert C. Enlow, president and CEO of the Friedman Foundation for Educational Choice; Joe Williams, executive director of Democrats for Education Reform; Michael B. Horn, executive director for education at the Innosight Institute; and Eva S. Moskowitz, founder and CEO of Success Academy Charter Schools.

With the RNC and November elections as a backdrop, we asked our contributors what – if anything – the federal government can do to promote school choice. It goes without saying that the responses are thoughtful, insightful and informative. They’re also diverse. They’ll give you plenty to think about – and even a few things to laugh at.

First up Monday: Secretary Spellings.

Nobody invoked Ronald Reagan this week and demanded that somebody (Randi Weingarten? President Obama? The local school board?) “tear down this wall,” but two school choice champions got close. Step Up for Students President Doug Tuthill used the Berlin Wall analogy yesterday in a redefinED post about the big-picture trends in ed reform. And in a beautiful coincidence, Robert Enlow, president and CEO of the Friedman Foundation for Educational Choice, did so today in an op-ed for CNN.

Nobody invoked Ronald Reagan this week and demanded that somebody (Randi Weingarten? President Obama? The local school board?) “tear down this wall,” but two school choice champions got close. Step Up for Students President Doug Tuthill used the Berlin Wall analogy yesterday in a redefinED post about the big-picture trends in ed reform. And in a beautiful coincidence, Robert Enlow, president and CEO of the Friedman Foundation for Educational Choice, did so today in an op-ed for CNN.

Wrote Enlow: “Just like the millions of East Germans who demanded freedom, we know that there are millions of parents that want to be removed from a system that uses a zip code to determine where their children must attend school.” He concluded, “Vouchers should be made available to children no matter if they are poor, disabled, from the middle class or from a family of 10, or from a rural, suburban or urban area. There should be no restrictions on who gets to choose, just like there were no restrictions on who could escape tyranny once the Berlin Wall fell.”

Also by coincidence, one of the nation’s biggest pollinators for school choice, Jeb Bush, delivered an ed reform speech in Colorado this week. He didn’t explicitly urge anyone to tear down any walls, either, but according to Education News Colorado he did implore the audience of 1,700 to “join reformers to make school choice both public and private the norm in our country."

Hmmm. Anyone else see speech potential here? Tampa. August. Fired-up delegates shouting "Tear down this wall!" as millions watch ...