by Allison Hertog

Charter schools often have an awkward, if not contentious, relationship with their local districts. That makes sense, as the public charter school movement is essentially a reaction to what can be a cookie cutter way of educating kids in neighborhood schools. Yet charter schools are part of the very same district (or state) that funds the neighborhood schools. It’s as if they’re siblings - they have the same parents but are often rivals - vying for funding, control, students, and political power among other things. Some district/charter relationships are cooperative, but others are rancorous, as illustrated by recent disputes in New York City and Pennsylvania. Not surprisingly, both those disputes involved special education to some extent – probably the most complex, expensive and controversial area of teaching.

Charter schools often have an awkward, if not contentious, relationship with their local districts. That makes sense, as the public charter school movement is essentially a reaction to what can be a cookie cutter way of educating kids in neighborhood schools. Yet charter schools are part of the very same district (or state) that funds the neighborhood schools. It’s as if they’re siblings - they have the same parents but are often rivals - vying for funding, control, students, and political power among other things. Some district/charter relationships are cooperative, but others are rancorous, as illustrated by recent disputes in New York City and Pennsylvania. Not surprisingly, both those disputes involved special education to some extent – probably the most complex, expensive and controversial area of teaching.

In most states, charter schools have the option of freeing themselves from these and other disputes by essentially becoming their own districts (legally termed Local Education Agencies or “LEAs”). But the vast majority of charters, even in states like California, where they have the option of becoming their own LEAs, have not taken on the responsibility of fully controlling their own special education programs – possibly out of fear, ignorance or politics. Fortunately, many of the more competent and high-achieving California charters - like KIPP, Aspire, and Rocketship - have chosen the path of autonomy and accountability and are leaving behind special education disputes with districts.

Where I work in Florida, where essentially charter schools don’t have the option of becoming their own LEAs (as is also the case in places like Virginia, Maryland and Kansas, and in New York for special education purposes), these special education disputes are problematic for many reasons. They’re terribly inefficient; they come at the expense of children; and they fly in the face of the charter school movement’s supposed commitment to autonomy and accountability.

To illustrate why it makes sense that some of the most competent charters are choosing to become their own LEAs and take full responsibility for special education, I’m going to use a business analogy that doesn’t carry the emotional baggage of disabled children.

Imagine a young entrepreneur who runs a new and successful Italian restaurant called “Vagare.” Vagare (i.e., the charter school in this story) has grown to serve roughly 300 customers a day. But in this city there’s a local corporate giant: “The Italian Restaurant Company” (i.e., the district). Founded in the late 1800’s, the IRC has virtually cornered the market on Italian restaurants. It serves thousands of customers daily, owns hundreds of locations, and controls restaurant supply firms and food supply chains. You get the picture.

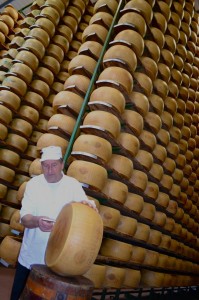

The IRC has contracted out some of its locations and provides certain supplies to Vagare and other smaller restaurants. Vagare locally sources most of its ingredients except for Parmigiano Reggiano cheese, which, by contract, it is required to obtain from the IRC, which buys it in bulk from Italy. (more…)

How can Florida attract highly regarded charter schools outfits like Rocketship and Yes Prep? Some of the state’s top education leaders hope to figure that out as they begin looking more closely at why those high-impact schools aren’t in Florida now.

“We need to do a better job, in my opinion as the state Board of Education chair, of serving our neediest children,’’ Gary Chartrand told redefinED Tuesday. “We need charter school operators that are really serious, cause-minded folks ready to do the hard, hard work of working in the toughest neighborhoods.”

Chartrand joined Gov. Rick Scott and Florida’s school choice director, Mike Kooi, in Orlando on Friday for a meeting with five of the country’s leading charter school operators (KIPP, Yes Prep, The Seed Foundation, Rocketship Education and Scholar Academies) and five superintendents from the state’s largest school districts (Orange, Miami-Dade, Duval, Hillsborough and Pinellas counties).

The group also included representatives from the Walton Family Foundation and the Florida Philanthropic Network, which includes the Helios Education Foundation and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Chartrand said.

The goal: identify the roadblocks for such schools and work toward solutions. There are a lot of variables, including per-pupil funding, which Chartrand said presents a significant challenge.

Florida ranks near the bottom nationwide, with an average of $9,572 spent per pupil, according to a recent Education Week analysis. By comparison, Vermont spends $18,924 per pupil and Utah $7,042.

“It does cost more to serve the highest-needs areas,’’ Chartrand said.

Chartrand helped bring KIPP to Florida and serves on the board of directors for the Jacksonville school (Chartrand donated $1 million toward the middle school and helped raise $9 million from the local business community). KIPP offers a longer school day and year, after-school programs and highly-qualified instructors to teach an academic program that focuses on college prep and character development.

Since KIPP was founded in 1994, more than 90 percent of its students have graduated high school and more than 80 percent have attended college. Of those, 40 percent have obtained college degrees.

The state wants to lure similar schools “by making long-term sustainability … a reality,’’ Chartrand said.

That might mean reducing startup costs, he said, perhaps by giving the schools access to the state’s Charter School Growth Fund. The fund is a $30 million reservoir created by federal Race to the Top dollars and philanthropic groups to benefit high-performing charters serving low-income students.

Another way to help is to streamline the charter school authorization process, Chartrand said.

In Florida, where there is no state authorizer, charter school operators apply through individual districts. But the process could go smoother if districts, state school choice officials and charter operators collaborate more closely on the front end, he said.