The nation’s first charter school law passed in 1991, the year after an improbably left-right coalition enacted the nation’s first modern school voucher program.

Ever since, charters have been the go-to “third way” solution: More regulated than private schools. More flexible than district-run public schools. Accountable to the public in more ways than either. And, crucially, amenable to worldviews of Democrats and Republicans.

But that may be starting to change.

Support for independently run public schools has eroded among elected Democrats. In a break from his predecessors in both parties, President Biden declined to issue a pro-charter proclamation and proposed cutting or restricting programs that support their growth.

And private education scholarships are sweeping the country: 18 states and counting have enacted education savings accounts or a similar mechanism allowing parents to direct public education funding to schools and providers of their choice. Growing numbers of large states like Ohio are opening private school voucher programs to all students. It’s clear this is where Republicans' education policy enthusiasm lies.

All of this has led some observers, like Andrew Rotherham of Bellwether, to worry charter schools are at risk of becoming a political orphan. As Republicans and Democrats pull further apart on education policy, will they strand charter schools in a barren middle ground?

It used to be a big deal when you had a pilot voucher program in places like D.C., Cleveland, and Milwaukee. Now another state passes universal choice and it's like, yawn. And whether you love them, hate them, or are a wait and see how they play out type, these programs are wildly popular right now. Speaks volumes about where the energy is.

Second, the Republicans are, on average, a lot more interested in ESA's than other choice options. They like the universal features, less regulation, less publicness, all of it. Democrats, meanwhile, mostly see those things as flaws. For a while there was stasis in this debate; charters were something of a compromise. Charters offered fewer regulations, could be universal, but they had key elements of publicness. They were an outpost for Democrats and a way station for Republicans. The ground has shifted, and post-pandemic, the energy is with rapidly expanding choice.

So, as private options expand, will that way station be abandoned?

Florida offers cause for optimism.

Last year, when Gov. Ron DeSantis signed HB 1, expanding private education scholarships and opening them to all students, he also signed a separate bill that, at long last, equalized facilities funding for charter schools (phased in over five years). The year before, legislation created a statewide charter school board. And this year, the state rolled out the welcome mat for Success Academy’s first potential expansion outside New York.

Each of those developments is a monumental success for Florida’s charter school movement that would have been unthinkable a few years ago, but happened with barely a peep from critics at about the same time the state was launching the largest expansion of private education choice in U.S. history.

The expansion of universal private education choice hasn’t led to the abandonment of charter schools. It’s opened up political space for the third-way solution to flourish, largely free of controversy. Florida’s charter schools have quietly and steadily grown to serve just shy of 400,000 students.

Last fall, our state education commissioner appeared on stage in Orlando, calling for public charter schools and private education options to join forces in a unified movement. That productive coexistence is already visible on the ground. The national education commentariat should take notice.

When it comes to education, a rising tide lifts all boats, Florida’s education commissioner told a national audience of school choice supporters and education entrepreneurs.

Look at Miami-Dade County, where leaders saw the tsunami coming and grabbed their surfboards.

“The district figured out that movement in South Florida was coming so fast and becoming so popular that the only way they could survive was to improve their services, (and) to improve their offerings,” Manny Diaz Jr. told those attending a conference sponsored by Harvard University called “Emerging School Models: Moving from Alternative to Mainstream.”

Despite the dire warnings that opponents have repeatedly issued since Gov. Jeb Bush and Florida lawmakers first began stirring up that school choice wave in 1999, none of the predicted devastation has come true, Diaz said.

Now, 70% of students in Miami-Dade attend a school of choice in the nation’s third-largest public school district. Those include charters, magnets, public schools with open enrollment policies and specialty academies, as well as the nation’s largest education choice scholarship programs.

Such a win-win situation didn’t stop the teachers unions and other school choice opponents from sounding the same alarms when he sponsored education choice legislation as a state senator.

“When we passed House Bill 1, they said the sky was going to fall,” Diaz said. “They were completely wrong.”

Over more than two decades, the legislation has created new options, including multiple scholarships with different funding sources that serve students with a variety of needs.

HB 1 was the latest advance. Signed by Gov. Ron DeSantis in 2023, it granted scholarship eligibility to all families regardless of income and converted all traditional private school scholarship programs to education savings accounts. The change allows parents the flexibility to spend their student’s allocation on tuition and fees, curriculum, part-time tutoring, and other approved expenses.

Diaz said the key to Florida’s success is its continuous quest for improvement, which at times has involved the passage of new expansions each year.

“It is a relentless chase of continuing to push,” he said. “The best defense is to be continually on offense.”

Rumors of the death of public education have been greatly exaggerated.

Rumors of the death of public education have been greatly exaggerated.

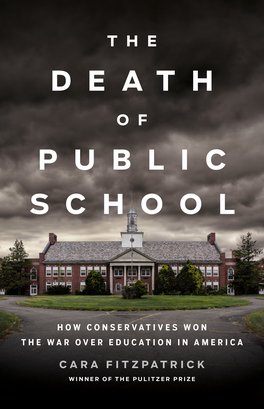

Any reader who gets past the cover of The Death of Public School: How Conservatives Won the War Over Education in America is likely to agree. The book never articulates the claim implied by its title.

It does, however, provide a thorough and insightful account of more than a half-century of fights in courtrooms and state legislatures to redraw the boundaries of public education to encompass more alternatives to district-run neighborhood schools.

Cara Fitzpatrick, an editor at the education news site Chalkbeat who won a Pulitzer Prize for an investigation of institutional failure in Florida's Pinellas County school district, introduces her narrative with statements from Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey and Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, who in the past two years have signed into law the nation's most ambitious expansions of educational choice.

Both governors declared public education includes a broad range of learning options funded and accessed by the public, from schools operated by districts to a la carte educational services purchased by parents using education savings accounts.

Fitzpatrick's history begins in the 1950s, when three separate strands of thought converged on similar ideas. Economist Milton Friedman argued for unleashing market forces by allocating public education funding to individual students. On religious freedom grounds, the Catholic cleric Virgil Blum argued public subsidies should help ensure all families had access to parochial schools. Across the South, segregationist lawmakers sought to evade Brown v. Board of Education by creating publicly funded private alternatives to public schools.

While the first two strands held the most enduring influence on the modern school choice movement, the third triggered years of legal battles. The NAACP's attorneys played Wac-a-Mole with attempts by Southern officials to evade integration orders. Both the civil rights organization and the Black parents it represented committed themselves to ensuring equal access to uniform public school systems—a stance that may help explain the NAACP's present-day skepticism toward charter schools and vouchers.

Meanwhile, Blum's efforts to secure public support for religious education suffered a crippling blow in Committee for Public Education v. Nyquist, in which the U.S. Supreme Court struck down a New York program offering tuition grants, tax credits and other subsidies.

And, beginning in the 1960s, a growing chorus on the left advocated new approaches to public education. These including Harvard sociologist Christopher Jencks and Kenneth Clark, a psychologist who helped secure the victory for desegregation in Brown. Fitzpatrick quotes Clark's 1968 essay that argued "public education need not be identified with the present system of organization of public schools. Public education can be more broadly and pragmatically defined in terms of that form of organization and functioning of an educational system which is in the public interest."

In the mid-'70s, these ideas were tested in Alum Rock, a North California school district that launched a short-lived experiment providing families with a diverse range of educational options that, to today's readers, resembled something like an array of publicly funded microschools. In Fitzpatrick's telling, Alum Rock's foray proved burdensome to administer, and families, while they valued additional options, were loath to unleash unfettered forces of creative destruction upon their local schools.

Voucher efforts gained momentum across the country, and in 1990 secured a major breakthrough in Milwaukee, thanks to a left-right alliance between Black community leaders frustrated with the state of public schools and Republicans inspired by Friedman. Voices on the left sought new forms of compromise, and in the process, furthered efforts to redefine public education. Minnesota's Democratic Gov. Rudy Pepich backed an expansion of public-school open enrollment. Teachers union head Albert Shanker warned the growing political momentum behind vouchers "poses the question of whether there will be public education in America." Years later, he would respond with a widely publicized proposal to support charter schools.

Meanwhile, a decades-long legal effort sought to turn the tide in courtrooms around the country. Led by Clint Bolick, an Arizona Supreme Court justice who started his career as a scrappy libertarian public interest attorney with a knack for publicity and an eye for sympathetic narratives, its eventual victory is embodied in William Rehnquist's progression from author of a dissent in the 1973's 6-3 Nyquist ruling to author of 2002's 5-4 decision upholding Cleveland's voucher program in Zelman v. Simmons-Harris.

In Zelman, defenders of the voucher program successfully persuaded Justice Sandra Day O'Connor, the critical swing vote, that public funding for private school tuition stood alongside charter schools and other reform efforts in a broader effort to secure the secular goal of improved education opportunities for the city's children. In other words, the vouchers program was part of a new definition of public education.

After the climactic legal battle in Zelman, Fitzpatrick's narrative fast-forwards toward the present, touching on the oft-panned Bush v. Holmes ruling in which the state Supreme Court temporarily stymied Florida's school voucher expansion and noting the creation of the nation's first education savings accounts. The narrative stops during the Trump Administration, just before the widespread school closures and the flourishing of new education options that redefined the boundaries of public education, and schooling, during and after the Covid-19 pandemic.

Fitzpatrick's treatment of these more recent events is confined to her introduction, where she quotes the conservative culture warrior Chris Rufo arguing that "to get universal school choice you really need to operate from a premise of universal public school distrust." Public polling and this year's legislative events suggest otherwise. Public schools and expansive choice policies like universal education savings accounts both enjoy majority support, and while trust in public schools is declining (alongside most other institutions in American life), universal choice is growing quickly at a time when distrust is far from universal.

Fitzpatrick laments that, in a polarized political climate, "it feels as if there's no middle ground to be found in education." But her own narrative points to where middle ground can be found. It's sketched out in the Zelman decision, and advocated, in varying ways, by such diverse figures as Ron DeSantis, Doug Ducey, Kenneth Clark, and Christopher Jencks: Public education must continue to flourish, and at the same time, it must be redefined to encompass a wider range of learning options chosen by parents.

Translating that middle ground into public policy will require thoughtful debates about how funding is allocated, how progress is measured, and how educators are regulated. This book doesn't advance a point of view on those big debates. But it offers valuable historical perspective on how to advance them.

Other views

Jay Greene, writing in Ed Next, and Naomi Schaefer Riley, writing in The Wall Street Journal, both argue Fitzpatrick's characterization of individuals and events suggest the author has a rooting interest against the school choice movement.

Publishers Weekly praises the book, tidily connecting the emergence of vouchers to fights over segregation in a far more simplistic fashion than Fitzpatrick does in her nuanced narrative, and incoherently contending that charter schools, which are public, "became a far more successful method of diverting resources from public education."

A starred Booklist review lauds the effort and concludes: "In Fitzpatrick’s capable hands, a sequel would certainly be much appreciated." The events of 2020-present would certainly provide plenty of material.

TALLAHASSEE, Fla. – A new organization aimed at ensuring families can choose the best education environment for their children launched today with an announcement from the group’s founder and chairwoman.

Former Collier County School Board member Erika Donalds said the School Choice Movement will focus on improving and expanding school choice in all its forms, adding that she became aware as a parent and a school board member that many families have insufficient options for school choice.

“Children are either on a waiting list for a scholarship or a charter school or they don’t qualify for one of the scholarships that are available, and they can’t afford a private school,” Donalds said. “Our goal is to give parents multiple high-quality options for their students.”

Joining Donalds in the effort are former Indian River School Board member Shawn Frost and former Duval County School Board member Scott Shine. Frost, who is a co-founder with Donalds and past president of the Florida Coalition of School Board Members, will serve as the organization’s advocacy director. Shine, who has served as a member of the Jacksonville Ethics Commission, will be a member of the executive board.

The group plans to advocate for school choice and the expansion of school choice options during the upcoming legislative session.

“We now have a governor who is very supportive of school choice and an education commissioner who is a tireless school choice advocate,” said Donalds, whose husband, Rep. Byron Donalds, R-Naples, serves on the Florida House Education Committee and is vice chair of the PreK-12 Appropriations Committee. “We want to make sure the expansion of school choice is No. 1 on the agenda.”

The group also plans to sponsor a speakers’ bureau and appoint regional directors who will fan out across the state in a grassroots effort to talk directly with families.

“We need to find a different way to reach parents with information about their options,” said Donalds, who helped establish Mason Classical Academy, a public charter school in Naples. “We also need to correct misinformation that’s out there about choice schools.

Among the myths Donalds plans to combat: the narrative that choice schools divert money from the public school system; the idea that charter schools underperform traditional public schools; and the notion that charter schools are not held to the same accountability standards as traditional public schools.

“For me, this is a moral issue our society needs to solve,” Donalds said. “Hoping students can play catch-up later in life is not an option.”

Watch the School Choice Movement launch video here for more information.

redefinED also spoke to Donalds after the James Madison Institute luncheon about her new organization. You can listen to that audio below.

School security criticized: School districts across the state are "not moving fast enough" to comply with the law passed last year that requires specific measures to improve security in schools, says the chairman of the state commission that investigated the Parkland school shooting. Pinellas County Sheriff Bob Gualtieri told the House Education Commission that school districts have "no sense of urgency" to have an armed guard in every school or to prepare for a potential attack, as required by the law. He suggested that districts that are slow to comply should be penalized by the Florida Department of Education. Tampa Bay Times. Florida Politics. Politico Florida. The Broward County School District is struggling to create safe "hard corners" in 20,000 classrooms. Finding one safe spot in a room that's big enough for all students is one problem, and principals say they aren't the safety experts who should be choosing the safest corner. Sun Sentinel. The Broward County School District is named one of six American K-12 districts to watch this year. As the site of the 2018 Parkland school shooting, Broward is at the center of the discussion on security in schools. Education Dive.

School security criticized: School districts across the state are "not moving fast enough" to comply with the law passed last year that requires specific measures to improve security in schools, says the chairman of the state commission that investigated the Parkland school shooting. Pinellas County Sheriff Bob Gualtieri told the House Education Commission that school districts have "no sense of urgency" to have an armed guard in every school or to prepare for a potential attack, as required by the law. He suggested that districts that are slow to comply should be penalized by the Florida Department of Education. Tampa Bay Times. Florida Politics. Politico Florida. The Broward County School District is struggling to create safe "hard corners" in 20,000 classrooms. Finding one safe spot in a room that's big enough for all students is one problem, and principals say they aren't the safety experts who should be choosing the safest corner. Sun Sentinel. The Broward County School District is named one of six American K-12 districts to watch this year. As the site of the 2018 Parkland school shooting, Broward is at the center of the discussion on security in schools. Education Dive.

DOE counsel named to court: U.S. Department of Education general counsel Carlos Muniz has been appointed to the Florida Supreme Court by Gov. Ron DeSantis. Muniz, 49, has no judicial experience but has been a lawyer for U.S. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos, former Gov. Jeb Bush and former Florida Attorney General Pam Bondi. This is DeSantis' third appointment to the court since he took office two weeks ago. Associated Press. News Service of Florida. GateHouse. Orlando Sentinel. Tampa Bay Times. Education Week. WPLG. Sunshine State News. (more…)