The Stanford Educational Opportunity Project has developed a new data tool called the “Segregation Explorer.” Let’s start with the definition of what is being measured in this data, which stretches from 1991 to 2022:

Segregation estimates in the interactive map represent the two-group normalized exposure index, which measures the difference between two groups’ exposure to one of the groups. For example, the White-Hispanic normalized exposure index compares the proportions of White (or Hispanic, equivalently) students in the average White and Hispanic students’ schools. A White-Hispanic normalized exposure value of 0.5 indicates that the proportion of White students in the average White student’s school is 50 percentage points higher than in the average Hispanic student’s school (ignoring the presence of other groups aside from the racial dyad of interest). For more information on this measure, see our brief.

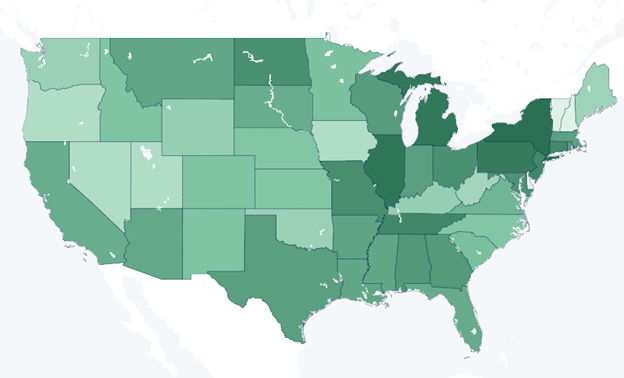

Okay so bottom line: darker is more segregated, lighter is less segregated. If we take the map back in time as far as it will go (1991) the White-Non-White student exposure index looks like this:

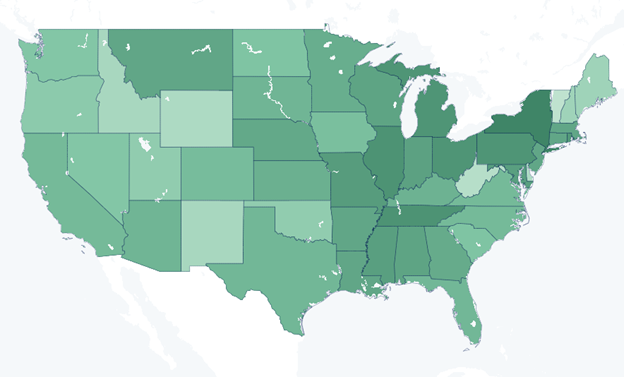

If you are squinting at your phone, New York was the school segregation capital of the United States with a white-non-white exposure index of .62. Fast forward to 2022 and the white-non-white exposure index map looks like:

Thirty-one years later, New York remains the school segregation capital, but at least it went down from .62 to .51.

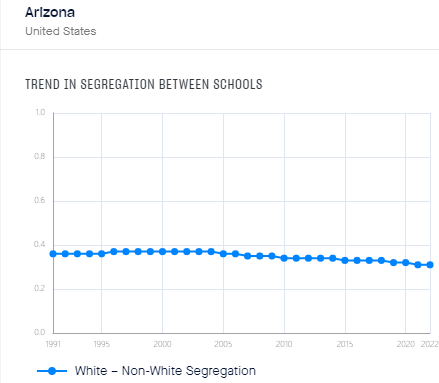

Choice opponents often claim that choice programs are increasing school segregation. A sadly typical example came in a guest column claiming that school choice had made Arizona school segregation worse than the 1950s and 1960s (!)

Well, school level data from the 1950s is a bit hard to come by, but let’s check the trend in the Stanford Educational Opportunity Index-White-Non-White exposure index trend:

So again if you are squinting at your phone, in 1994 (the year Arizona’s charter and open enrollment laws passed- kicking off the K-12 choice era) the white-non-white index stood at .36 and in 2022 the same measure had dropped to .31- which just happens to be one half of the level of New York in 1991.

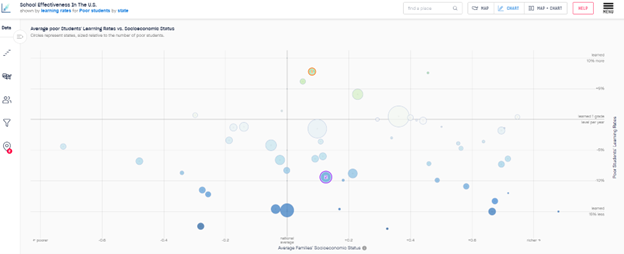

The Stanford Educational Opportunity Project also has updated figures for the academic growth of poor students. Let’s see how that worked out for Arizona (1) and New York (2):

Somebody must be benefiting from the $38,000 per student spent in New York’s public school system, it’s a shame that the list does not include the students.

Editor’s note: This guest post is by Chris Lubienski, professor of education policy at the University of Illinois, where he is director of the Forum on the Future of Public Education. He is at twitter.com/CLub_edu

Some social justice advocates are quite enthralled with the possibilities of school choice. While district and enrollment boundaries reflect segregated residential patterns in the U.S., choice allows families to select schools across these artificial barriers, eradicating an important institutional impediment to equity. Moreover, schools then must compete to attract students, just like businesses strive to attract customers.

Charter schools reflect these ideals. It’s worth remembering that some of the early adopters of this innovation were progressive educators frustrated by the disservice that district-run public schools were doing to marginalized children. Charter schools embody the advantages of choice: giving parents alternatives, creating competition with public school districts, and offering the possibility of more socially integrated education based on interest, not race or residence. Compared to, say, vouchers, charters are the choice policy most favored by liberals. (Of course, charters also are embraced by conservative market advocates.)

Since the charter movement began, there have been debates about whether charter schools represent privatization. The recent issue of the Oxford Review of Education, which focuses on privatization, education and social justice, considers such questions and the equity implications.

In the classic sense of the term, it’s difficult to argue that charter schools “privatize” public education. Unlike, say, the transfer of state-run industries to private owners in Latin America in the 1980s and 1990s, ownership of public schools is generally not being shifted to private hands. In fact, one could argue the opposite is happening, as some private schools have opted into the publicly funded system to become charter schools, and many families have left tuition-based private schools for “free” taxpayer-funded charter schools.

Yet it’s also difficult to ignore the large-scale shift in American educational governance. Within a few short years, large swaths of urban systems run by elected school boards have been transferred to private (for-profit and non-profit) management groups. In Los Angeles, 100,000 students are now in charter schools. More than 1 in 3 public school students in Detroit, Kansas City and the District of Columbia now attend privately run charter schools. Policymakers are aggressively shutting down Chicago’s neighborhood public schools and inviting in private charter operators. Louisiana embraced charter schools as the primary reform model for re-making public education in post-Katrina New Orleans, where some 80 percent of students now attend charter schools. This is a remarkable record for a school model that didn’t exist 25 years ago.

So in this broader view, it would seem charters serve as a vehicle for moving governance of public education away from public control. Moreover, the charter movement is serving as the primary entry point for private investment seeking to reconfigure public education into a site for profit-making. (more…)

Editor's note: This is the fourth and final post in our series commemorating the 50th anniversary of Dr. King's "I Have a Dream" speech. Dr. Vernard Gant is director of Urban School Services with the Association of Christian Schools International.

by Vernard T. Grant

As the nation marks the 50th anniversary of Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream" speech, speculation abounds as to what the content of that speech would be if delivered today. It is noteworthy that in all of his speeches and writings, Dr. King had little to say about education beyond segregated schools and low performance by black students. He apparently thought that once the racial barriers of discrimination and social injustices were removed, educational disparities would self-correct. It would not be much of a stretch to suggest he would be appalled to discover that according to the latest NAEP report, black children in 2011 are still not performing in reading at the level of white children in 1970 (just two years after his death).

Here’s my take on what his reaction would be, a slight variation on the words from his speech: It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro [children] a bad check which has come back marked "insufficient funds." But we refuse to believe that the bank of [educational] justice is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of [educational] opportunity of this nation. So we have come to cash this check -- a check that will give us upon demand the riches of [educational] freedom and the security of [educational] justice. We have also come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of now. [Brackets mine]

Just as in the days of the civil rights movement, a grave injustice is transpiring today that is adversely and profoundly impacting its victims. A quality education, essential for cashing the promissory note that all men would be guaranteed the inalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, is being systematically denied families that do not have the economic means to secure one for their children.

A quality education is a purchased commodity. It depends on the financial wherewithal of individual families. It can be purchased either by paying tuition to private schools, or by paying higher mortgages and property taxes in neighborhoods with high-performing public schools. Parents who have low and moderate incomes simply do not possess the financial means to secure such an education for their children. They are bound to accept what is offered in schools assigned on the basis of where they live. They have no choice and no freedom in their children’s education. To compound matters, they are often told, from the public’s standpoint, that they should never have a choice because if they did, it would financially cripple the public school system. Translation: the important thing is not the best interest or well-being of the child, but the best interest and well-being of the system.

To add insult to injury, parents are told this by opponents of school choice and educational justice, all of whom exercise choice in where their children go to school. As a general rule, people of means naturally send their children to schools that effectively educate them. No caring parent (no matter how dedicated to a cause) would put their child in a school and sacrifice his or her education on an altar they know would fail their child. The tragedy is in the hypocrisy; what these individuals practice personally (school choice for their own children), they oppose politically for other folks’ children. They act in the best interest of their children, but insist the children of less economically advantaged families remain bound to a system that does not benefit them but rather benefits from them.

What is needed today and what Dr. King would call for is educational justice. (more…)

Editor's note: This is the first in a series of posts we're running this week to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Dr. King's "I Have a Dream" speech.

I grew up in a Minnesota city of 100,000 with - in my time - one black family. My introduction to the reality of public school segregation came in 1962 as - now at Northwestern in Chicago - I agreed to probe the public schools of the district on behalf of the U.S. Commissioner of Education. The racial separation was there as expected, but there was one big surprise; I was astonished to find enormous disparities, not only in taxable local wealth - hence spending - among the hundreds of Illinois districts, but even in individual school-by-school spending within the Chicago district itself. I wrote about both problems, sprinkling research with “action” including marches and demonstration both in Chicago and in Selma (prior to the main event there).

My interest in deseg politics had already provoked a law review article on the risks of anti-trust liability for King et al. who were planning boycotts of private discriminators. On the strength of that essay, Jack Greenberg, then director of the NAACP Inc. Fund, invited me to meet with King and his lieutenants at dinner in Chicago to discuss the question. We spoke at length - mostly about boycotts but also about schools. By that time I was already into the prospects for increasing desegregation in Chicago, partly through well-designed school choice.

I won’t pretend that I recall the details of that evening. What I can say is King’s mind was at very least open to and interested in subsidies for the exercise of parental authority - which clearly he valued as a primary religious instrument. I took my older boys next evening to hear him at a South Side church and, possibly, to follow up on our conversation, but he had to cancel. We heard sermons from his colleagues, some to become and remain famous. I did not meet King again.

King’s “Dream” speech does not engage specific public policy issues - on schools or anything else. Essentially a sermon, it is a condemnation of the sins of segregation and an appeal to the believer to hear scripture, with its call for indiscriminate love of neighbor, as the life-task of all who recognize the reality of divine love for us - his image and likeness. It is purely and simply a religious appeal that declares the good society to be one that rests upon benign principles that we humans did not invent but which bind us. I don’t know King’s specific understanding of or attitude toward non-believers, but this document clearly rests the realization of the good society upon its recognition of our divine source and its implication of the full equality of all persons.

Given that premise and the Supreme Court’s insistence upon the “wall of segregation” in the public schools, plus - on the other hand - the right of parents to choose a private religious education, the logic is rather plain.

Private schools live on tuition, and many American families couldn’t afford to enroll then or now. If low-income families were to exercise this basic human right and parental responsibility enjoyed by the rest of us, government would have to restructure schooling to insure access to an education grounded upon, and suffused with, an authority higher than the state. Given the economic plight of so many black parents, the only question would be how to design the system to secure parental choice without racial segregation by private educators.

And that possibility was to be the principal crutch of “civil rights” organizations in hesitating about subsidized choice. (more…)

Bill Maxwell, a highly regarded African-American columnist with the Tampa Bay Times, has used a new Hechinger Report to argue that charter schools are introducing a second wave of “white flight” in public education. His argument tracks the work of the Civil Rights Project at UCLA, which has called charter schools a “civil rights failure” and echoes the assertion of University of Minnesota researcher Myron Orfield that charters are “an accelerant to the normal segregation of public schools.”

Bill Maxwell, a highly regarded African-American columnist with the Tampa Bay Times, has used a new Hechinger Report to argue that charter schools are introducing a second wave of “white flight” in public education. His argument tracks the work of the Civil Rights Project at UCLA, which has called charter schools a “civil rights failure” and echoes the assertion of University of Minnesota researcher Myron Orfield that charters are “an accelerant to the normal segregation of public schools.”

Some of these findings are certainly cause for concern. But racial integration in American education is rooted in nearly a half-century of social policy and federal court intervention, which makes isolated conclusions about the new role of charter schools problematic. Yes, it could be that charter schools cause more racial segregation. It is also possible something else could explain the racial demographics. It could be, for example, that charter school enrollment merely reflects the racial makeup of the neighborhoods in which they operate.

In that sense, examining the racial ratios in charter schools is but one part of a much larger equation.

Maxwell’s column was inspired by an article in the Hechinger Report that began with an anecdote about a very white elementary charter school south of St. Paul/Minneapolis, Minn. The charter school, Seven Hills Classical Academy, was 82 percent white while the surrounding Bloomington Public School District averaged 57 percent white.

However, the school district obscures the vast range within the public schools themselves. Among Bloomington public elementary schools alone, the ratio of white enrollment ranged from 15 percent to 81 percent. In other words, there are also public schools with similar degrees of racial segregation.

The assertion that school choice somehow exacerbates segregation and separatism in American society surprises me every time it pops up. The ideal of traditional public education, a “common school” available equally at no cost to all citizens to impart a high level of academics as well as a core set of American values, has always been a myth. Yet it has amazing staying power despite the facts.

The assertion that school choice somehow exacerbates segregation and separatism in American society surprises me every time it pops up. The ideal of traditional public education, a “common school” available equally at no cost to all citizens to impart a high level of academics as well as a core set of American values, has always been a myth. Yet it has amazing staying power despite the facts.

Put aside a hundred years of state-sanctioned racism that outlawed education for slaves, and then engendered “separate, but equal” schools for another 90 years until the 1954 Supreme Court decision banned the practice. Let’s look at how this “common school” system serves Americans now.

The statistics on K-12 education in the Department of Education’s "The Condition of Education, 2011" report are informative. Nationally, 31 percent of African-American students are in schools that have 75 percent or more African-American students. The figure is nearly 33 percent for Hispanic students. Nationally, 62 percent of whites attend a school with a population over 75 percent white, while those schools serve around 7 percent of the African-American and Hispanic populations.

When city demographics are analyzed, the segregation of traditional public schools dramatically jumps. Forty-two percent of African-Americans and 39 percent of Hispanics are in schools with 75 percent or more of those same students. Not surprisingly, school enrollment and especially urban school enrollment reflects how a public education monopoly assigns students to schools - by zip codes.

Another way to look at how this “common school” system is serving us is the distribution of the free and reduced lunch (FRL) population, which the Department of Education identifies as a proxy for low-income students. High-poverty elementary schools, those with 75 percent or more of an FRL population, enroll 45 percent of Hispanic students and 44 percent of African-American students. For whites, the enrollment is 6 percent in high-poverty schools. Nationally, urban areas account for 29 percent of our student population, yet 58 percent of all students in high-poverty schools live in our cities.

Combine this data with dropout statistics in the 40-60 percent range for inner-city minority populations, and abysmal academic outcomes for so many of the remaining students, and you have the “common school” myth stripped bare. (more…)