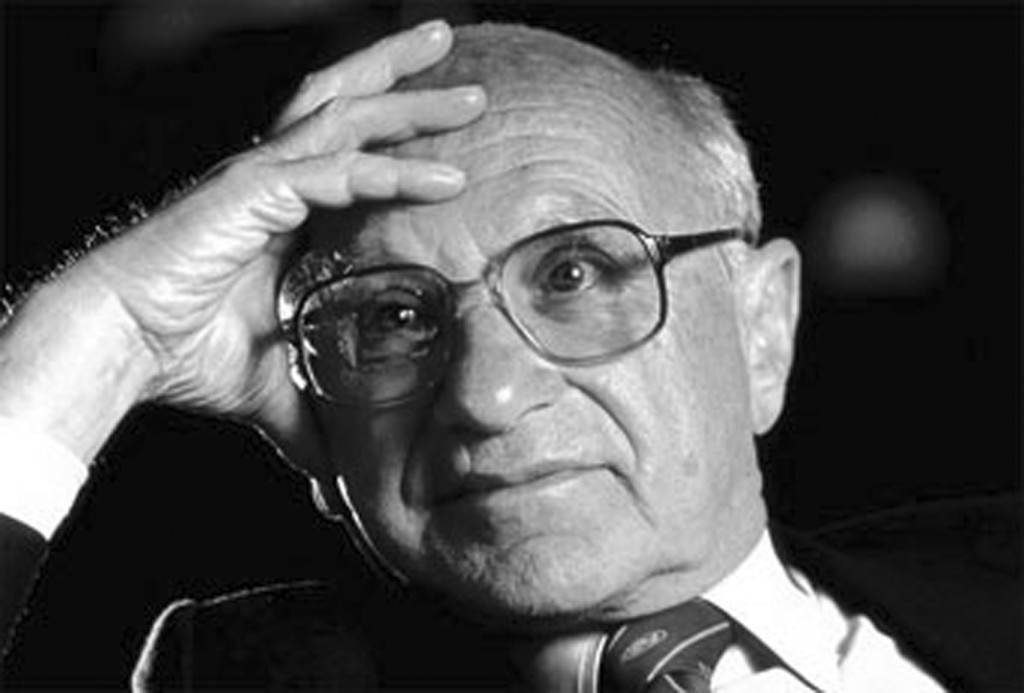

American economist Milton Friedman received the 1976 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences. His vision was to give parents, not government, control of their child's education.

In the 1960s, Milton Friedman was my repeated guest on “Problems of the City” on Chicago radio KQED-KFMF, and later, I was a guest on his TV show to debate United Federation of Teachers president Albert Shanker. We – Friedman and I, not Shanker – shared the hope for a free market in schooling but differed regarding both its justification and appropriate design.

He favored a subsidy of equal value for the child of every parent, then would let the market rip! It was to him an economic sin to favor lower-income families in either the amount of the subsidy or the design of regulation for participating schools. The focus for him was not on the role of the parent, but rather the achievement of simplicity and laisse-faire in the economy.

Friedman was never to change his mind; in fact, he took the opportunity along the way to promote just such an unregulated voucher as a popular initiative in California in 1978, designed so as to compete with a prior and more lower-income-oriented initiative written and promoted by Steve Sugarman and myself. So divided, neither proposal made it to the ballot.

He did, however, succeed at inspiring a covey of monied and dedicated marketeers who have to this day remained willing to support a let-her-rip approach to choice. Their generous enthusiasm has given birth to a covey of pure-market non-profit organizations, today’s most plangent cheerleaders for choice – that is, for equal subsidy for both the poor and for the already comfortable family, and with nearly zero regulation of the chosen providers. These well-intending market folk have succeeded largely in giving subsidized parental choice the image of Friedman himself.

This picture may have held very little glamour for voters, but paradoxically has been much appreciated by the captains of the public school unions; it allows them to picture subsidized choice as another deceit of the rich and powerful (other than themselves).

When Sugarman and I began designing model choice statutes in the ’60s, our first invention was a complicated device intended to arm the lower-income parent with an array of choices, including the level of the subsidy in both public and private sectors. Over time, our published inventions have become more simplified but ever with the central aim of empowering the lower-income parent to act as responsibly as does the comfortable suburbanite.

After this half-century of division between Miltonites and “voucher left” (their pet name for people like us), could it be that the time has come to consider what sort of compromise might give political life to our shared democratic hope? Could we learn a bit from Ohio, Florida and Washington, D.C.? Could it be both “fair and free market” for us lefties to concede at least a trophy amount to the well-off in recognition of their civic role as parent, while awarding the poor the full economic reality of that same parental responsibility and authority?

The success of any choice system in empowering the poor would, of course, require some commitments from the (freely) participating school – private or (at last) “public.” For example, the participating school could retain complete liberty to select two-thirds of its admissions, but then to select the rest at random from among its unchosen applicants.

In designing such statutory proposals, a half-dozen other forms of commitment by the participating schools would be considered to ensure fairness. Each of these compromises in design could be bargained by the “voucher left” and the Miltonites. These variations were examined in some detail and modeled in our 1978 book, “Education by Choice: The Case for Family Control” – and in our later published models.

It will not necessarily be politically hurtful to the cause of choice that Betsy DeVos will be gone, and that the president-elect appear as mendicant of the union elites. The individual state will still decide whether and in what precise form those who need choice should receive it. And, at some point, in another paradox, SCOTUS may well take occasion to lend its voice to the rescue of the penniless under the Constitution. This could well be the time for voucher folk, “left” and right, and in every state, to become happy co-conspirators.

Editor’s note: Among many other things, Father Andrew Greeley, who passed away last week, was a champion of Catholic schools. According to the New York Times obituary, “His research debunked the received view at the time that Catholics had low college attendance rates. He found instead that white Catholics earned bachelor’s degrees and pursued advanced degrees at higher rates than other whites, and he attributed their success to the quality of education in parochial schools, a controversial assertion in a time of public school ascendancy.” As John E. Coons writes in this post, the school choice movement also considered him one of its own.

Andrew Greeley was a friend and a puzzle. We first met in 1978 at a conference of the National Catholic Educational Association. James Coleman - that other splendid Chicago sociologist - had written the introduction to a new book of Steve Sugarman’s and myself; it was about school choice, and Coleman thought Andy and we should connect. Sporadically, over the next 30 years we enjoyed a rather lively reciprocity.

I had known Greeley’s work on Catholic schools and their role in the larger civic order. His 60’s book with Peter Rossi - "The Education of Catholic Americans" - was suggestive to anyone hoping to liberate the inner-city child from a public system that only helped secure his permanent dependence. Sugarman, William Clune, and I took added confidence in arguing (1968, 1970) that any constitutional solution to our warped and irrational distribution of support among public schools not foreclose the state’s assistance to families to make their own choice - including private religious schools.

In respect of school choice Greeley contributed principally - but very effectively - as an intellectual source. His work in the 80’s with Michael Hout on the social picture of life in Catholic schools and their intellectual and social payoff was, I think, a constant resource for those more on the front line. He was emotionally committed to the institution and publicly regretted what he saw as the shameful and unnecessary closing of parish schools in Chicago. All choiceniks saw him as an ally. If not a spear carrier, he was the ideal quartermaster. His relative distance from politics preserved his academic stature, and – prudently - he stayed in the intellectual background and fed the troops. (more…)

Colleagues in the American Center for School Choice have convinced me to add a more personal note to my recent 100th birthday blog about Milton Friedman. They ask that I describe my connections with - and occasional disconnections from - the great man. I am honored to be consulted and hope to contribute light sans heat. Though there is no avoiding one’s perceptions of human limits, correct or otherwise, my aim here will be neither to praise Caesar nor to pester him. Our 40-year acquaintance centered on a very public issue - that of subsidized school choice. The civic importance of this question justifies a story or two and, inevitably, a rough and rambling interpretation of our own relationship.

These stories could bear on the historic and continuing question of whether Friedman’s free market style of argument was the most efficacious to advance his own project. It is just possible that his prodigious contribution might best be honored today by considering a shift in the civic and moral mood music supporting our common pursuit of genuine authority and responsibility for less well-off parents.

Milton and I met a half-century ago in Chicago. He taught economics at UC; I taught law at Northwestern. He was maybe 18 years my senior. Milton became a frequent guest on my weekly (unsponsored, largely unheard) radio talk show. Over the air, the two of us would argue about appropriate government responses to the various challenges posed by the young and diverse civil rights movements.

In 1962, I had written what became a controversial report on racial segregation in Chicago public schools for the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. My head was bursting with solutions for our educational calamities. These solutions included vouchers, but soon it was clear that I was bit more inclined than he toward government guardianship of equal access for poor and black families to schools that would participate in any subsidized system of choice. Milton was opposed to most of what seemed to me rather modest commitments by the school. He was confident that subsidy plus an unfettered market offered the best long-term protection for our civic values.

I think we liked each other. Milton was a tough guy and could be intimidating. Others may recall his classic trick of breaking into the middle of the opponent’s argument with “Excuse me,” and then proceeding to turn the conversation in whichever direction he preferred. But I never felt personally beset. When, later, he became a TV personality (the late ‘70s), Milton, to my glad surprise, invited me to represent the pro side in a TV debate on vouchers. The opponent was, like Milton, my sometime friend—the formidable Albert Shanker. It was fun and altogether coherent.

By then we had both moved to the San Francisco Bay area. I was pushing a popular voucher initiative that Steve Sugarman and I had designed; I was confident that my Friedmanic connection would generate financial support from business folk. We wined and dined with Rose and Milton and their admirers; we invested precious time and what was, for us, considerable capital in the campaign. In the end, to our surprise, Milton successfully urged our targeted business angels to wait for a more appropriate—i.e., less regulated—proposal. They took his advice. We bit the dust.

This turn of events was a bit difficult to digest. (more…)

It will take a centrist voice to advance the debate over school choice, and few individuals know that better than Jack Coons and Steve Sugarman of the University of California at Berkeley. The two law professors have thought more about parental empowerment in education during the last 41 years than perhaps anyone else living today, and they have established a rare progressive voice in school choice in an enterprise that has taken root at Berkeley.

That effort is the American Center for School Choice, an advocacy group that recognizes that the power of the marketplace alone in education reform has limited political appeal. “The empowerment of ordinary families will come only as the fruit of a credible coalition of recognized centrists,” the center’s leadership states. To that end, Coons and Sugarman have invited Gloria Romero and redefinED host Doug Tuthill to join them on the board. Tuthill is the president of Step Up For Students, which administers a Florida Tax Credit Scholarship program that today serves more than 34,000 students with bipartisan backing, and he also serves as the Florida coordinator for Democrats for Education Reform. Romero is DFER's California chief and a former Democratic state senator in California.

Those moves are the latest in the center’s ambitions to elevate the national debate over school choice. It has already hosted two national conferences and has plans to assemble more gatherings in the future. It sees choice as a moral imperative and as a public policy that has profound social effects on the poor families who benefit, and it is looking for credible researchers to examine just how profoundly. It sees a role for faith-based schools in a system of public education that is continually setting new precedents of pluralism and diversity, but the center recognizes that only a broad, interfaith coalition of support can advance that discussion (the center also named to the board Robert Aguirre, the chief executive of the Catholic Association of Latino Leaders and appointed Kathy Jamil, the director of the Islamic Schools League of America, to its list of associates).

But while the center has collaborated with more free-market oriented groups who favor liberating the parent and the educator from “government” schools, it knows what is – and isn’t – needed for the school choice movement to gain political traction.

“When our political discourse proposes subjecting education to the same market forces as banks, airlines and electric power, we give aid and comfort to the enemies of school choice,” Coons wrote in a 2001 article in America. “Voters care more about the visible hand of the parent than they do about the invisible hand of Adam Smith. And they are right to do so.”

When Tuthill and Romero addressed the center’s conference in April, the assembly was exposed to two active Democratic voices that have largely been overlooked since the Reagan administration appropriated the quarterback role of school choice from the War on Poverty. But just as Coons and Sugarman framed the idea of choice as equity in 1970, the American Center for School Choice is trying to guide us away from the political extremes and look with clarity and reason on the value of parental empowerment. Look to it as an emerging centrist voice in a conversation accustomed to simple ideological divisions.