This is the latest post in our series on the center-left roots of school choice.

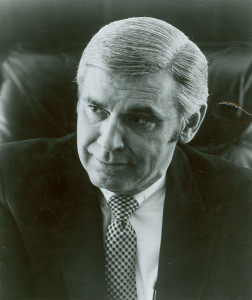

U.S. Congressman Leo Ryan was a popular Democrat who favored school choice. In 1978, he started working with Berkeley law professors Jack Coons and Stephen Sugarman on a plan to put school choice on the statewide ballot in California. An early poll showed 59 percent of voters were in support.

All of us know Lincoln was assassinated. But not many know the twist of fate that left historians asking: What if? Had it not been for a clown of a cop named John Frederick Parker – who was supposed to be protecting the president at Ford’s Theatre, but instead slipped next door to the Star Saloon – America after the Civil War may have coursed in dramatically different directions.

The history of school choice has its own forgotten twist of fate.

It involves Berkeley law professors, a murderous cult, and U.S. Rep. Leo Ryan, a school choice Democrat. Given relentless attempts by choice critics and the press, in this age of Trump and hyper-tribalism, to portray choice as right-wing madness, it’s worth revisiting Ryan and what happened 40 years ago. Would white progressives still view choice as a Red Tribe plot had white progressives been the first to plant the flag? And in big, blue California to boot?

In 1978, Berkeley law professors Jack Coons and Steve Sugarman laid out a social justice case for school choice in “Education by Choice,” a book that also offered a detailed policy blueprint. The prevailing system of assigning students to schools by zip code, they argued, was elitist and dehumanizing to low-income families. Their sweeping alternative included private school vouchers and independent public schools (which we now call charter schools). It also included visions of a system that would allow parents to build their kid’s educational programs a la carte, like today’s education savings accounts.

In 1978, Berkeley law professors Jack Coons and Steve Sugarman laid out a social justice case for school choice in “Education by Choice,” a book that also offered a detailed policy blueprint. The prevailing system of assigning students to schools by zip code, they argued, was elitist and dehumanizing to low-income families. Their sweeping alternative included private school vouchers and independent public schools (which we now call charter schools). It also included visions of a system that would allow parents to build their kid’s educational programs a la carte, like today’s education savings accounts.

Coons and Sugarman wanted to plant seeds, not spark an instant revolution.

But then, serendipity.

Congressman Ryan, enjoying his third term representing the San Francisco Bay area, was a former public-school teacher and a product of Catholic schools. “Education by Choice” moved him. As fate would have it, his cousin went to church with Coons. So he had her invite Coons to dinner.

Ultimately, the professor and the congressman decided they’d try to get the California Initiative for Family Choice on the statewide ballot. All they needed was enough signatures. Ryan agreed to be the face of the campaign.

Choice couldn’t have found a better spokesman. Before Ryan was elected to Congress, he was a state lawmaker who practiced what one newspaper called “investigative politics,” and his aide Jackie Speier – now U.S. Rep. Jackie Speier – called "experiential legislating."

Ryan worked as a substitute teacher to immerse himself in high-poverty schools. He went undercover to experience Death Row at Folsom Prison. As a Congressman, Ryan trekked to Newfoundland to investigate the slaughter of baby seals, and even laid down on the ice to save a seal pup from a hunter.

It’s not a stretch to think Ryan’s popularity would have rubbed off on the ballot initiative.

This is the second post in our series on the Voucher Left.

Way back in 1978, when Bee Gees ruled the radio and kids dumped pinball for Space Invaders, a couple of liberal Berkeley law professors were promoting a variation on “universal” school vouchers that they believed would ensure equity for the poor. Along the way, they foreshadowed a revolutionary twist on parental choice that would make national headlines nearly four decades later.

John E. “Jack” Coons and Stephen Sugarman didn’t use the term “education savings accounts” in their book, “Education by Choice.” But they described a sweeping plan for publicly funded scholarships in terms familiar to those keeping tabs on ESAs. They envisioned parents, including low-income parents, having the power to create “personally tailored education” for their children, using “divisible educational experiences.”

John E. “Jack” Coons and Stephen Sugarman didn’t use the term “education savings accounts” in their book, “Education by Choice.” But they described a sweeping plan for publicly funded scholarships in terms familiar to those keeping tabs on ESAs. They envisioned parents, including low-income parents, having the power to create “personally tailored education” for their children, using “divisible educational experiences.”

To us, a more attractive idea is matching up a child and a series of individual instructors who operate independently from one another. Studying reading in the morning at Ms. Kay’s house, spending two afternoons a week learning a foreign language in Mr. Buxbaum’s electronic laboratory, and going on nature walks and playing tennis the other afternoons under the direction of Mr. Phillips could be a rich package for a ten-year-old. Aside from the educational broker or clearing house which, for a small fee (payable out of the grant to the family), would link these teachers and children, Kay, Buxbaum, and Phillips need have no organizational ties with one another. Nor would all children studying with Kay need to spend time with Buxbaum and Phillips; instead some would do math with Mr. Feller or animal care with Mr. Vetter.

Coons and Sugarman were talking about education, not just schools, in a way that makes more sense every day. They wanted parents in the driver’s seat. They expected a less restricted market to spawn new models. In “Education by Choice,” they suggest “living-room schools,” “minischools” and “schools without buildings at all.” They describe “educational parks” where small providers could congregate and “have the advantage of some economies of scale without the disadvantages of organizational hierarchy.” They even float the idea of a “mobile school.” Their prescience is remarkable, given that these are among the models ESA supporters envision today.

It's also noteworthy given a rush to portray education savings accounts as right-wing.

In June, for example, the Washington Post described the creation of the near-universal ESA in Nevada as a “breakthrough for conservatives.” School choice would likely be a top issue in the 2016 presidential campaign, the story continued, with leading Republicans like Jeb Bush, Scott Walker and Marco Rubio all big voucher supporters and Democratic front-runner Hillary Clinton opposed. The story pointed out Milton Friedman’s conceptualizing of vouchers in 1955, then added, “The idea was long thought to be moribund but came roaring back to life in 2010 in states where Republicans took legislative control.”

It’s true that in Nevada, Republicans took control of the legislative and executive branches in 2014, and then went on to create ESAs. But it’s also true that across the country, expansion of educational choice has been steadily growing for years, and becoming increasingly bipartisan in a back-to-the-future kind of way. Nearly half the Democrats in the Florida Legislature voted for a massive expansion of that state’s tax credit scholarship program in 2010. About a fourth of the Democrats in the Louisiana Legislature voted for creation of that state’s voucher program in 2012. New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo has been fighting for a tax credit scholarship in that bluest of blue states – an effort in which he’s joined not only by many other elected Democrats, but by a long list of labor unions.

These Democrats are sometimes accused of being sellouts – often by teachers unions and their supporters, who have been especially critical of Cuomo. But the truth is, they can draw on a rich history of support for educational choice grounded in the principles of the American left.

The recent history of ESAs isn’t quite as polarizing as the Post suggests, either. (more…)