Isaac Wilbanks, left, and Joshua Akabosu are two of the original seven students who still attend Dickens Sanomi Academy in Plantation, Florida.

Joshua Akabosu was nearly hit by a truck when he was 10. He had run from school that day, as he often did. Announced to the class he was going home, then bolted through a door and into the neighboring streets.

School officials told Joshua’s mom, Juliet Sanomi, what she already knew: that they could no longer accommodate her son. He was a flight risk and posed a danger to himself and others.

Joshua, now 20, is on the autism spectrum. He has attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. At the time of his accident, he was just learning to speak in complete sentences.

“I took him to (his district) school, they couldn’t handle him. I took him to private schools, same thing,” Juliet said. “And no fault to the schools. These children don’t come with manuals.”

But where does a single mother turn when she has nowhere else to go? When homeschooling is not an option because she is pregnant, and because she wants her son to interact with other children?

In Juliet’s case, she turned to herself. She started her own school.

Dickens Sanomi Academy in Plantation is celebrating its 10th year. It has 170 students, most of whom receive the Family Empowerment Scholarship for Students with Unique Abilities (FES-UA), which is managed by Step Up For Students.

Joshua graduates this spring. He was one of the original seven students during the school’s first year.

“I am very grateful for the (FES-UA) because it was difficult. He wasn’t asked to be born with autism and it’s been a difficult road,” Juliet said. “I thank God for the scholarship because he’s done very well, the best he’s able to do, and that’s because we had the funds to do that.”

Joshua was the school’s first student. The second student came through a chance meeting with the mother of an autistic child. The mother was standing in the parking lot outside of a school. She was crying because school officials just told her the same thing Juliet had recently been told about Joshua.

To continue reading, click here.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Colleen Hroncich, a policy analyst with Cato's Center for Educational Freedom, appeared Sunday on the center's website.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Colleen Hroncich, a policy analyst with Cato's Center for Educational Freedom, appeared Sunday on the center's website.

My oldest child is graduating from college tomorrow, so it has me thinking about our educational journey—which could best be described as eclectic. At various times, we used private school, district school, and cyber charter school. But we ultimately landed on homeschooling.

That doesn’t mean they were literally learning at home every day. My kids participated in co‐ops, hybrid classes, dual enrollment, athletics, and more. This gave them access to experts and plenty of social time.

It can be scary taking charge of your children’s education—I remember feeling very relieved when my oldest received her first college acceptance. But today there are more resources than you can imagine to help you create the best education plan for your children’s individual needs and interests. And with the growth of education entrepreneurship, the situation is getting even better.

For starters, you don’t have to go it alone. The growth of microschools and hybrid schools means there are flexible learning options in many areas that previously had none. One goal of the Friday Feature is to help parents see the diversity of educational options that exist. To see what’s available in your area, you can search online, check with friends and neighbors, or connect with a local homeschool group.

If you don’t find what you’re looking for, the good news is that there’s also more support for people looking to start new learning entities.

The National Microschooling Center is a great starting place if you’re considering creating your own microschool. The National Hybrid Schools Project at Kennesaw State University is also a tremendous resource. There are businesses—like Microschool Builders and Teacher, Let Your Light Shine—whose focus is helping people navigate the path to education entrepreneurship. And grant opportunities, like VELA and Yass Prize, can help with funding.

We were fortunate to be in an area with a strong homeschool community and therefore had plenty of activities to choose from. But I’m still a bit jealous when I speak to parents and teachers each week and hear about the amazing educational environments they’ve created.

There’s also an abundance of online resources available, from full online schools to à la carte classes in every subject imaginable. If you like online classes but want an in‐person component, KaiPod Learning might be just the ticket. These are flexible learning centers where kids can bring whatever curriculum they’re using and work with support from a KaiPod learning coach. There are daily enrichment activities, like art, music, and coding, as well as social time.

One of the best parts of taking charge of your children’s education is that it puts you in the driver’s seat. If your children are advanced in particular subjects, they can push forward at their own pace. In areas where they struggle, they can take their time and be sure they understand before moving ahead. (One potential downside is that this takes extra discipline and can be challenging. But it’s tremendously beneficial overall.)

These nonconventional learning paths can be great for kids who don’t want to go to college, too. Flexible schedules free up time to pursue a trade, music, performing arts, sports, agriculture, and more. As kids get older, they can increasingly take charge of their own education. This lends itself to developing an entrepreneurial outlook, which is vitally important in a world where technology and public policy are constantly changing the workforce and economic landscapes.

“One size doesn’t fit all” is a common saying among school choice supporters. But this is more than just a slogan. It’s an acknowledgement that children are unique and should have access to learning environments that work for them. Public policy is catching up to this understanding—six states have passed some version of a universal education savings account that will let parents fund multiple education options.

If you’ve considered taking the reins when it comes to your children’s education, it’s a great time to act on it. Whether you choose a full‐time, in‐person option, a hybrid schedule, or full homeschooling, you’ll be able to customize a learning plan that works best for your kids and your family.

And you may even become an education entrepreneur yourself and end up with a fulfilling career that you never expected.

An athletics coach at Noble High School in Noble, Oklahoma, wants kayaks for his students so they can learn to navigate on the school’s pond. One option for making the project a reality would be DonorsChoose, a foundation that already has funded 61 projects at the school.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Mike Goldstein, a former Boston charter school administrator, appeared last week on the Thomas B. Fordham Institute’s website.

“Chicken Coops, Trampolines and Tickets to SeaWorld: What Some Parents are Buying with Education Savings Accounts.” That’s the title of a news story from The 74, cross-posted to the The Guardian, about states like Arizona that are passing laws giving parents money to use for private or homeschooling.

The emailed version is titled “ESA Boondoggle.” The charge? “Some find the rules, as one former state chief put it, ‘incredibly permissive.’”

Under the excitable headline is a balanced article. These Arizona parents aren’t just buying books and tutoring with their education accounts; they’re also buying kayaks, skating lessons, and roping lessons. One poor vendor gets the raised-eyebrow treatment: “The sword casting instructor, for example, said he would teach students ‘archaeology, physics, history and metallurgy.’”

I’m not here to debate the usual stuff: Who decides, parents or educators, on the last 1 percent of dollars spent? Who decides what is a reasonable expenditure?

Instead, my contrarian take is four-part:

A Boston elementary school teacher has twenty kids at $25,000 per student per year of government spending. Why is her discretionary share of that $500,000 just a few bucks? Why couldn’t she control $10,000 per year (2%) to spend directly on her students? Why does a school administrator get to control all 100%?

To continue reading, click here.

Students at Casa Ranch Montessori Homeschool Cooperative, a program that encourages children to be divergent, independent, and self-directed learners, work on a project with Eye of a Scientist founder and teacher Neymi Mignocchi. Photo courtesy of Casa Ranch founder Priscilla Yuill.

MIRAMAR, Fla. – Broward County isn’t one of the locales featured in “The Geography of Genius: Lessons from the World’s Most Creative Places.” But if author Eric Weiner is game for a follow-up, he might want to visit this suburb where Johnny Depp grew up to see what’s happening in the big back yard with the palm-thatched chickee, the garden rows covered with iguana-proof mesh, and the giant, white yurt.

This is Casa Ranch Montessori, a new but already thriving homeschool co-op.

Inside the yurt is a woman with a Ph.D. in neuroscience. She’s showing six students ages 9 to 11 how to make LED Christmas trees, with diodes and copper wire and button batteries.

This is Neymi Mignocchi, owner of Eye of a Scientist, a new but already thriving enrichment program.

With Mignocchi’s guidance, the students use pliers to bend wire around each arm of a diode, then wrap the segment with electrical tape. Along the way, they learn the difference between open and closed circuits, and insulators and conductors.

One by one, tiny light bulbs turn on.

At growing numbers of innovative little schools in Broward County, this is how education is happening – with a burgeoning ecosystem of schools and specialists working in synch.

This is the “Broward County Renaissance.”

“I just love the collaborative feel with all these wonderfully talented people,” said Priscilla Yuill, a 12-year Montessori teacher who started Casa Ranch in 2020. “Each and every one of these super humans share a common goal, and that is the will to revolutionize education. When educators are given the opportunity to connect, collaborate, and create, that’s when magic happens.”

Broward is home to 2 million people and America’s sixth-biggest school district. It’s also a hotspot for a mushrooming cluster of cutting-edge little schools.

That would be extraordinary enough; in fact, it’s drawing national attention.

But what makes Broward even more fascinating is that it’s not just the schools.

Whatever Miracle-Gro is in the soil is also yielding high-quality specialists like Eye of a Scientist. Instead of starting their own schools, these other entrepreneurs are focusing their talents on a single subject – and filling the niches the schools either can’t fill themselves, or now no longer need to.

Shiren Rattigan, the daughter of a truck driver and a public-school teacher, started Colossal Academy in 2020 after a decade of teaching in public and private schools in models that in her view did not work for students or teachers.

Education entrepreneur Shiren Rattigan put it this way: “We’re the soup. They’re the spice.”

Rattigan is the founder of one of those cutting-edge schools, Colossal Academy, and in the thick of the Renaissance. She’s the one who came up with the name, which sounds audacious until you see how many distinctive, interrelated providers have cropped up in this palmy sprawl north of Miami.

Casa Ranch and Colossal Academy both tap into multiple specialists, who in turn work with many other little schools. Specialists like …

Toni Frallicciardi, who co-founded Surf Skate Science with her husband Uli, majored in ocean engineering at the Florida Institute of Technology. Their nonprofit started off with six students in 2018. Last year, it served more than 2,000.

Other specialists in Broward focus on art, music, photography, PE. Some are more traditional providers, like the YWCA that offers classes on entrepreneurship. Others are unique, like the outfit that offered flying lessons to low-income students.

Even more are coming.

A former science teacher who works with Rattigan is creating a business that will customize field trips to nature parks and the Everglades. She expects her new venture to be more fulfilling than her teaching gig – and better paying.

All of this will rev into even higher gear if more families gain access to more flexible choice scholarships.

More than 70 percent of Florida families are eligible for traditional school choice scholarships, which can be used for private school tuition. But most cannot access state-funded education savings accounts (ESAs) that would allow them to access a richer variety of services and providers a la carte. If more families had that power, clusters like the one in Broward would become even more dynamic. And lower-income families in particular would benefit.

“That would level the playing field for a lot of people,” Rattigan said.

The schools and specialists tied to the Renaissance are also emerging in Miami-Dade County to the south and Palm Beach County to the north. But Broward is its heart. And the vibe is infectious.

“We’re all learning from each other, we’re all getting energy from each other,” said Mignocchi, who worked as a neuroscientist for six years before starting Eye of a Scientist.

Broward is no stranger to learning options.

Of the 14 big urban districts in Florida, Broward ranks No. 3 in the percentage of students enrolled in charter schools (at 19 percent) and No. 4 in the percentage of students in private schools (at 15 percent).

Over the past five years, no big district has seen a bigger jump in home schoolers. Last year, Broward had 10,412 of them, a 151 percent increase from 2017.

The county is home to one of America’s most successful charter school networks, Charter Schools USA; to stellar faith-based schools like Abundant Life Christian Academy; to highly regarded Black-owned schools like Piney Grove Academy. “Alternative” private schools also have roots here, with exemplars like BB International, aka “The Renaissance School.”

The thing about Broward, though, is the innovation just keeps rolling.

The latest wave includes Kind Academy, Compass Outreach, Take Root Forest School and so many others.

Many of these newer entities were founded by former public school teachers. Several have earned big-time accolades:

To be sure, challenges remain.

Some schools, like Colossal, participate in Florida’s school choice programs. But others, like Casa Ranch, cannot, given current limitations with scholarship flexibility.

A student at Casa Ranch Montessori Homeschool Cooperative crafts a Christmas tree from diodes, copper wire and button batteries, learning the difference between open and closed circuits, insulators and conductors.

Yuill started Casa Ranch when schools closed during the pandemic. She wanted her children outside and learning, so she and some friends started a pod. As word of mouth spread, the pod grew.

Casa Ranch chooses to work with outside specialists in some areas to build a stronger, more vibrant, more hands-on curriculum. The co-op does Montessori-based science lessons, for example, but works with Mignocchi to enrich them and infuse them with real-world application.

“She’s the missing link because she’s an expert scientist who can really tap into students’ curiosities,” Yuill said. “She does all the hands-on learning after we do the subject learning.”

Mignocchi’s family fled to the U.S. from Venezuela when she was eight years old. She started Eye of a Scientist after deciding to homeschool her son.

She said she knows from experience with public schools, as a student and a tutor, where the gaps are with science instruction. Her goal is fill those gaps, and to inspire students to think like scientists.

She said she most wants to help low-income students, so they avoid the hurdles she faced.

“I was a straight-A student in the best classes in high school, but I went to college and almost flunked out,” Mignocchi said. “They did not prepare me at all.”

That’s another reason ESAs are promising, she said.

Lower-income families are less able to access alternative learning systems, even though those models may be ideal for their kids.

A little flexibility with funding would mean a renaissance for all.

When “edupreneur” Amy Marotz, second from right, decided to launch Awakening Spirit Homeschool Collaborative on a 15-acre single-family home site outside of Stillwater, Minn., she looked beyond traditional teacher training colleges for guidance, turning instead to an organization in Pennsylvania that helps teachers build the schools of their dreams.

Editor’s note: This article is the third in a series that explores how today’s teachers are being prepared – or not – for the classroom now that education choice has become normalized. You can read the first two articles here and here.

When Amy Marotz wanted to start a private homeschool collaborative for children with sensory issues, she didn’t rely on a traditional college of education for training, even though she had a master’s degree from one.

Instead, the former English teacher turned to Microschool Builders, a startup based in Pennsylvania. The firm, founded in 2019 by veteran educator and administrator Mara Linaberger, offers an array of services to prepare those seeking to become school founders. Most of the clients are teachers who want to trade their jobs in traditional classrooms for more fulfilling work in education.

Marotz, who leads Awakening Spirt School in the Minnesota Twin Cities area, is not alone in her desire for better opportunities. A 2022 survey commissioned by the National Education Association revealed that 55% of educators who responded said they were more likely to leave or retire sooner than planned. Reasons cited were burnout, general stress from the pandemic, student absences, and unfilled job openings leading to heavier workloads.

A recent special report from Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog, and EdChoice, highlighted 10 Florida educators who left the traditional classroom to start alternative education models. Top reasons included frustration with public schools, a desire to create options that better served their own children, a desire to create options that better serve teachers.

As more state legislatures approve education choice scholarships that can fuel growth in this segment, traditional four-year universities have yet to develop training options for teachers who see the benefit of bypassing traditional schools in favor of establishing alterative models.

Though some have embraced innovation, it has been mainly within the framework of traditional school systems. Most notable among these are Arizona State University’s Next Education Workforce initiative, which seeks to recruit and retain traditional school teachers by redesigning the workplace.

In Tennessee, Austin Peay State University created a three-year program in partnership with school districts and community colleges to attract and retain non-traditional students to the profession. The program, which was adopted statewide, became the first federal apprenticeship model of its kind and a model for the nation.

Still, when it comes to equipping these “eduprenuers,” resources are limited to companies that cater to established teachers who are burned out on traditional schools and seeking the opportunities to reconnect them with the love for teaching that drew them to education in the first place.

“Any attention to education innovation or alternative learning models that exist outside of traditional schooling are typically marginalized in these programs, if they are addressed at all,” said Kerry McDonald, a senior education fellow at the Foundation for Economic Education and author of the 2019 book “Unschooled: Raising Curious, Well-Educated Children Outside the Conventional Classroom.”

“This has long been true, but is perhaps more apparent today as microschools, homeschooling, learning pods, and similar models become increasingly popular,” she said.

Why have traditional colleges of education ignored this group in favor of the public school system? No one knows for sure, but experts offered some ideas.

First, the old way is simpler and scalable. It’s easy to plug in, and most education professors were trained in the traditional school model.

“They’re not entrepreneurs for the most part. It’s just not part of their DNA,” said Eric Wearne, an associate professor in the Education Economics Center at Kennesaw State University in Georgia and the director of the university’s National Hybrid Schools Project. The initiative seeks to document and analyze the variety of independent actors who are creating new forms of K-12 schooling outside of the conventional education system.

Wearne called most programs “thinly veiled arms of the HR department of the school district,” which they depend on to provide internships for their majors. States also have certification rules for teachers and working with public school districts allow for easier compliance.

“They’ve got to place a ton of students every semester,” Wearne said. “They have incentives to work with the school system.”

Also, the variety and complexity of all the different non-traditional methods make training a challenge. If colleges wanted to offer such training, it would be best to let majors choose to specialize in a certain model and follow a track rather than create new programs that address all non-traditional forms together as all are unique.

For example, requiring training in classical education, which emphasizes memorization, would be a poor fit for someone who considers such memorization pointless, he explained. A school also could add certifications in certain specialties or offer courses in business entrepreneurship for those who want them.

He said the private companies may be best equipped to train those who feel called to leave the beaten path because “most of those (graduates) are going to working for public school systems or private schools that look functionally similar.”

Another challenge to traditional universities is that as states continue to approve education choice policies that allow innovation to increase and flourish, the role of the teacher is also quickly changing. The idea of who counts as a teacher has also been expanded, with some companies that specialize in self-directed learning using guides instead of certified educators.

In a recent report on the transformative effects of the pandemic on learning, the Center on Reinventing Public Education recommends that the traditional schools themselves should be the ones to change the way they have done education for decades to capitalize on the innovation that sprang up during the pandemic and incorporate a more bottom-up approach.

It recommends new models in which teams of teachers take on different responsibilities based on their strengths and interests rather than have one teacher in charge of 20 to 30 students all day. Such innovations might keep teachers in the profession and provide better learning opportunities for all students regardless of where they get their education, said Travis Pillow, innovation fellow and senior writer at the center.

“We have to start treating teachers as knowledge workers the same way we do doctors and lawyers,” he said.

Wearne said that should extend to teachers’ colleges. If they don’t find ways to adapt as demand for non-traditional options increase among students and teachers, enrollments could decline as startups fill the void.

“If you have a natural decline in enrollment and huge market demand, then choosing not to meet that need does bode well for long-term prospects,” he said.

The Early Learning Residency Program at Austin Peay University proved to be exactly what recent graduate Malachi Johnson was looking for when he graduated from high school: a college education and a guaranteed job. The day he received his diploma, he began his career as a teacher in Tennessee’s Clarkesville-Montgomery County School System.

In her 20s, Heather Fracker set her sights on becoming a respiratory therapist. But as John Lennon observed, “Life is what happens when you’re busy making other plans.”

Fast forward two decades, and Fracker, a 43-year-old single mom to two middle schoolers, is pursuing a new dream. In two years, she will be a fully credentialed elementary school teacher thanks to an accelerated program that began in her hometown.

“Never in a million years did I think I’d want to be a teacher,” Fracker said.

Heather Fracker, left, is working on a bachelor’s degree in education through Tennessee’s Early Learning Residency Program with help from her mentor, Belinda Cornell.

But subbing and volunteering in schools in her area changed her mind. She began working toward a childhood development associate credential to teach pre-kindergarten. Fracker did so well that the Tennessee Early Childhood Training Alliance, a statewide organization with locations at multiple colleges and universities, nominated her for the Early Learning Teacher Residency Program at Austin Peay State University, then in its third year.

“At first, I said no,” she said, “because my plan was already in place.”

But alliance leaders won her over by telling her it was a terrific opportunity, that she easily could add a pre-K endorsement by taking an exam. Now, Fracker is at the head of a third-grade classroom three days a week and working toward a bachelor’s degree in the evenings.

Going back to college in mid-life to pursue a new career can be prohibitive due to the cost and time commitment involved. But the Clarkesville-Montgomery County School System, and more recently, the state of Tennessee, are banking on individuals like Fracker who offer a solution to the teacher shortage and retention issues that have plagued the profession for years – a challenge that has become more severe as teachers leave traditional classrooms to start their own schools or choose not to teach in the first place.

In Tennessee, the “Grow Your Own” program started in 2018 as a partnership between the school system and Austin Peay, a public institution with 8,418 undergraduates.

Located about 12 miles south of the Kentucky state line and about an hour’s drive from Nashville, U.S. News & World Report ranked the university 41st out of 135 among regional colleges in the South.

The Clarksville-Montgomery County School System employs 2,550 teachers who are charged with delivering instruction to 37,900 students, half of whom are classified as economically disadvantaged. Almost 16% have disabilities, and 5% have a first language other than English.

Leaders at both organizations came up with the idea in response to shared concerns discovered during meetings aimed at improving their partnership. Chief among them: the critical teacher shortage.

“We both wanted to address the issue of the teacher shortage, of not having enough graduates in high needs areas, especially STEM, and we both wanted to add diverse students to our programs,” said Lisa Barron, associate dean of the Eriksson College of Education at Austin Peay.

The commiserating quickly turned to brainstorming.

“Once we really started getting serious about how we impact this, we realized that if we were to completely redesign teacher education, it probably would not look like what it does today,” Barron said.

For the program to be successful, the groups decided, several factors had to come together. It would have to attract individuals who were settled in their hometowns, preferably those already connected to schools, including volunteers, aides, custodians or bus drivers or others without college degrees.

They agreed the program needed to be free to students and that it must be flexible enough for them to work and support their families while they trained. Additionally, they agreed, the program had to move faster than the traditional four-year university route, and it had to provide support in the form of wrap-around services to help students navigate challenges.

Prentice Chandler

“We sometimes have made becoming a teacher harder than it has to be,” said Ericksson College dean Prentice Chandler. “I know a university is not the easiest place to navigate, and that’s our fault.”

Chandler dismisses the notion that no one wants to be a teacher these days, advancing the idea that the teacher shortage can be solved by removing barriers to well-designed programs. Chief among those barriers, Chandler believes, is what he sees as a lack of cooperation between teacher prep programs and school districts.

“We train teachers and we let them loose, and you hire them, and that’s it, we’re done,” he said. “The responsibility of preparation of teachers belongs to colleges of education working in tandem with their school partners. Without that sort of paradigm shift, I don’t think any of this work happens.”

In its first year, the Early Learning Teacher Residency Program accepted 20 recent high school graduates and 20 Clarksville-Montgomery County teachers’ aides. The model in place at that time is basically the same today.

Participants are employed throughout the program as teachers’ aides in classrooms led by the school system’s most experienced and highly effective teachers at elementary schools in lower-income areas. As employees, they receive a salary and benefits. The supervising teachers receive a stipend for each participant they mentor.

During their three-year residency, candidates must master all state-required competencies. They also must pass all state-required certification exams. After the final school bell rings each day, participants take classes toward a bachelor’s degree in education. They study year round with no summer break. All costs, including tuition, fees, textbooks, and anything else associated with the program, are covered.

Initially, participants were split between the university and the school system. That changed in 2021, when the state took notice of the program and expanded it by awarding $100,000 grants among 13 higher education providers across the state.

“It’s accelerated, but it’s not easy,” said Sean Impeartrice, chief academic officer for the Clarksville-Montgomery County School System. He stressed that graduates get the same quality of training as traditional education majors.

Since the program’s inception, Austin Peay has forged partnerships with community colleges, which offer two-year education degrees at no cost to students. After earning a two-year degree, the students take their remaining classes from the university.

Once program participants graduate, they must spend at least three years teaching in the school districts where they did their residency.

Program administrators say the wraparound support participants receive is key to ensuring they successfully complete their training.

“We work really hard to get rid of the many barriers that residents may have,” said Lavetta Radford, the education pipeline facilitator for the Clarksville-Montgomery County School System. “They may be academic, financial, or related to mental health. Sometimes life happens. We have residents who have lost children, who are taking care of aging parents, had surgery, or they may just need a space to come and work.”

For Fracker, the biggest challenge has been trying to spend time with her children. Now, most of her evenings are reserved for study. The course terms have been condensed from 12 weeks to seven weeks, so the workload is heavier.

“I have had to have many heart-to-heart talks,” she said. “They ask for a lot of time I can’t give. I have to keep reminding them that mommy is doing this to give them a better life.”

Her mentor, Belinda Cornell, is always there to offer Fracker everything from tutoring to a word of encouragement.

“She brings great classroom management skills,” said Cornell, a 38-year teacher who supervises two residents in addition to Fracker. “She has really knocked it out of the park … I’m there supporting her, but she’s taking the lead now.”

Soon after it began, the program began garnering state and national attention. The state of Tennessee has expanded it to 13 universities that partner with 65 school districts.

In January, Tennessee became the first state in the nation to be approved by the U.S. Department of Labor to establish a permanent Grow Your Own apprenticeship program, with the Teacher Residency program established by Austin Peay and Clarksville-Montgomery County as the first registered apprenticeship program.

“Tennessee’s leadership in expanding its Grow Your Own program is a model for states across the country that are working to address shortages in the educator workforce and expand the pipeline into the teaching profession,” U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona said in a news release.

Cardona pointed out that the program could not be more urgent or necessary as educators attempt to recoup COVID-19 learning loss.

Malachi Johnson toyed with the idea of becoming a teacher while a senior in high school but was nervous about paying college tuition for four years. In August, he was among the first class to graduate from the “Grow Your Own” teacher training program at Austin Peay State University.

More recently, the Tennessee Department of Education and the University of Tennessee System, comprised of university campuses throughout the state, announced plans to establish a $20 million Grow Your Own center to bolster the pipeline programs. The state also is working with the Council of Chief State School Officers to launch similar programs in other states.

Impeartrice, the school system’s chief academic officer, acknowledged that the program has not completely solved the teacher scarcity problem but said it has helped shrink the shortage. About 160 residents are now enrolled in the program.

“If we didn’t have the program, we’d be 150 teachers short rather than 50 teachers short,” he said. “We can close that gap. That’s doable.”

In August, the school system was able to at least narrow the gap as Austin Peay State University graduated its first class of newly minted residents, ready to serve as full-time teachers in the Clarksville-Montgomery County School System.

“It’s crazy because the night of graduation, I go to work for an open house so I can meet my students,” said Malachi Johnson, who was hired at a local elementary school. “I am jumping right into it and can’t wait.”

Fracker agrees. She expects she’ll feel more like a veteran than a newbie when she graduates with three years of teaching experience on which to draw, fully prepared to embark upon her new dream.

Tranquil Teachings Learning Center began during the COVID-19 pandemic as a “pandemic pod” and has evolved into a microschool serving 45 students.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Kerry McDonald, an education policy fellow at State Policy Network and senior education fellow at the Foundation for Economic Education, appeared Friday on washingtonexaminer.com. Check back for a feature story about Tranquil Teachings Learning Center from reimaginED reporter Tom Jackson.

When it comes to the current state of education, there is a lot to be upset about. Widespread education disruption over the past 30 months has led to significant learning loss among K-12 students and a growing youth mental health crisis.

But there are some bright spots. The education turmoil since 2020 has prompted more parents to pay attention to what is happening in their children’s classrooms. Many of them feel a renewed sense of ownership over their children’s education and are increasingly seeking or starting microschools, learning pods, hybrid schools, homeschooling collaboratives, and other innovative educational models.

Teachers have been similarly empowered to exit the classroom and create small co-learning communities or schooling alternatives.

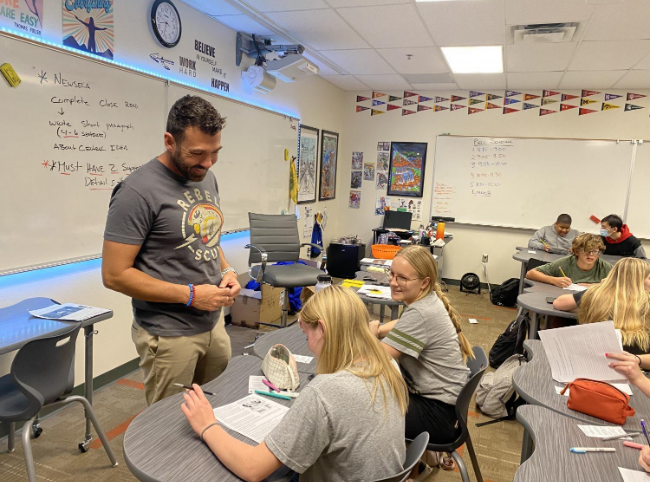

That’s what Jill Perez did. A mother of four children who began her career as a public school teacher in New Jersey more than 20 years ago, Perez pulled her children out of school in 2020 and formed a "pandemic pod" with other local families to maintain social and academic enrichment. Her pod was so successful that she evolved it into a microschool, a small, multi-age learning community, in leased commercial space last fall, opening with 45 students.

Students in her program, called Tranquil Teachings Learning Center , are legally recognized as homeschoolers and can attend the drop-off program part-time or full-time, depending on their family’s needs and preferences.

She also recruited several teachers from New York City public schools to work in her microschool. These educators were burnt out from two years of classroom commotion and were happy to trade a higher salary for more flexibility, autonomy, and creative expression.

"Often in the public school setting, students and teachers feel like second-class citizens because education is becoming less and less human," said Perez. "At Tranquil Teachings, we have a culture where everyone feels valued, and this mutual respect also drives a desire for high performance."

To continue reading, click here.

Shaun Reedy, a member of a teaching team at Westwood High School in Mesa, Arizona, says the Next Education Workforce program allows him to collaborate with other teachers, learning from their teaching styles. The model, born at Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College at Arizona State University, aims to better prepare teachers for the classroom and boost teacher retention.

Editor’s note: Today, reimaginED brings you the first in a three-part series on how the nation’s most innovative teaching colleges are preparing education majors to enter, and more important, stay in the field. We begin with the Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College at Arizona State University, ranked as the nation’s 12th overall best teachers’ college in U.S. News & World Report’s 2023 survey. The university has 4,833 students, the largest among all universities ranked, and reported $73.5 million in funded education research.

Teachers are expected to assume many roles. In a single day, a teacher must be an expert on content as well as pedagogy – also known as the practice of teaching – a social worker, a bus loop monitor, a role model, a data analyst, a trauma interventionist, and the sole classroom manager for 30 students.

In other words, all things to all students, all the time.

It’s no wonder teachers are retiring early or transitioning to other professions. According to the U.S. Department of Education, 35% fewer college students chose to major in education between 2011 and 2016. A Center for American Progress analysis of data collected by the Department discerned a 28% decline in students completing teacher preparation programs from 2010 through 2018.

Carole Brasile, dean of the Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College at Arizona State University and co-author of an article about the mounting teacher crisis published in the newsletter of the American Association of School Administrators, has a specific concern.

“More disturbingly,” Brasile wrote, “for some time we have seen that most new teachers leave the profession within three years.”

At the same time, schools continue to produce the same, often disappointing outcomes.

The Next Education Workforce initiative, developed by Arizona State University’s Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College, addresses the challenge of teacher retention by transforming a one-teacher, one-classroom environment into a collaborative and more creative team-based model at locations such as Stevenson Elementary School in Mesa, Arizona.

Leaders of teacher preparation programs at Arizona State believe those two situations are linked. Recruiting more teachers and training them better will not solve the problem, they say. Only a redesign of the profession, the workplace, and how education majors are prepared for both will improve outcomes for students and teachers.

That’s the purpose behind Next Education Workforce, an ASU initiative launched five years ago that aims to craft a better future for educators, many of whom are graduates of ASU, and more personalized learning for students. The models are now in place at 27 of the state’s schools.

“Education, in general, is broken,” said Randy Mahlwein, assistant superintendent for secondary education at Mesa Public Schools and the district’s liaison to Next Generation Workforce, which involves 19 of the district’s schools, many of which are Title 1 eligible based on high numbers of low-income students. “The archaic way we designed education and implemented it over the last hundred years was designed and created for a different workforce than exists today.”

Mahlwein added that putting unrealistic expectations on a teacher and then measuring progress by annual high-stakes testing, where scores are driven by economics, is inherently unfair.

“If they had put a time frame on Thomas Edison to invent the light bulb, and then measured all his failures and discredited him to a point where he would have been washed out of the industry, he would have never invented the light bulb,” he said.

Arizona State’s Next Education Workforce program has replaced the traditional “one-teacher-one-classroom” model in Mesa schools with a teams-based model. While team teaching isn’t new, Mahlwein said, the ASU program’s models are different.

“Those (earlier) teams were working in isolation from students,” he said. “This is more wrapping teams that distribute expertise around teams of students without the limitation of time.”

At Westwood High School, for example, about 900 ninth graders are distributed across six teams. Each team shares about 150 students and is comprised of at least three certified teachers and a lead teacher, who both instructs and manages the classroom.

Other educators join the core depending on students’ needs. Their roles include special educators, teachers of English language learners, teacher candidates who are completing residencies, and paraeducators.

The models, which vary from school to school, entail “collaborative and interdisciplinary work during instructional time, as well as before and after it,” according to Basile and Brent Maddin, the program’s executive director. Planning periods are also collaborative, with daily common planning time that allows teachers to create cross-curricular lessons, discuss student work and design personalized experiences for each learner.

Instruction incorporates project- and inquiry-based learning to allow students to learn more deeply. Teachers are joined by community partners who also serve as team members. Gone is the traditional bell schedule.

Sometimes, large groups of students meet with all four core teachers for instruction, and other times they break out into small project-based groups based on student interest and teacher expertise.

In a project on the United Nations, for example, teachers work with students as they survey the globe brainstorming for ways to improve challenges.

Those challenges could touch on food or clean water, Mahlwein said. The teachers weave the standards of science, history and English into the lessons and present a bell-free three hours of instruction.

“Kids can be seen moving through the doors from classroom to classroom,” he said. “The learning is very much student-based, and everyone’s working at their own pace, with a little bit of voice and choice.”

Yet it’s no free-for-all, Mahlwein said. Teachers work within boundaries, and their students do, too.

Mary Lou Futon Teachers College, headquartered on Arizona State University’s Tempe campus, offers programs on all four of ASU’s campuses, online and in school districts throughout the state. Named for ASU education alumna and businesswoman Mary Lou Fulton, the college has two divisions: teacher preparation and educational leadership and innovation.

While teachers at participating Mesa schools are at various stages of introducing the Next Generation Workforce program, they all are honing their skills in specific areas as determined by leaders at Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College. Those areas, as studied in order, are:

So, how is this transformational way of training teachers working?

Arizona State leaders say early results from the pilots are showing fewer student referrals, suspensions and failed classes in secondary schools and better reading and math scores and attendance rates at elementary schools. Parents are asking for the new models to be schoolwide, and teachers are asking to be assigned to teams.

Meanwhile, the university is working with its school partners to develop a research agenda to generate evidence-based knowledge about the relationships between the models and outcomes for teachers and students. Leaders have contracted with Johns Hopkins University to serve as an external evaluator and research early implementation and impact of Next Education Workforce models.

“Ultimately, we need to prove we’re right about this,” said Maddin, the program’s executive director. “Are the models we’re building better for learners and teachers? If so, in what ways? How can we make them work better? We think that is a research agenda worth investing in.”

But Mahlwein of Mesa Public Schools already sees evidence of positive outcomes in the smiles on students’ and teachers’ faces and in workforce surveys. A team of teachers at a school in Tempe recently gave the program high marks in a promotional video.

"A job that once felt really isolating to me just does not have that feeling any more," said Mary Brown, a teacher at SPARK School at Kyrene de las Manitas. "When the day is trying, difficult, you have five other people to lean into and bounce ideas off of, and we’re always talking about students; we're always talking about achievement, and we’re always giving each other ideas and feedback on how we can do better."

Zoe Glover, a teacher candidate at Arizona State University who is on Brown's team, said the program benefits teachers and students.

"It's very enjoyable to come to work every day," she said. "And it's such a positive experience to be in the classroom. Not every student is going to connect with every single teacher, but when there're six teachers, there's no students getting lost in the cracks."

Mahlwein said their comments echo what he has observed at the participating schools in district.

“What we’re seeing at the schools that have done this at a pretty good clip are some statistically significant positive results coming from teachers working on teams,” he said. “They are across the board reporting more job satisfaction and more happiness in the workplace.”

Mahlwein added: “For so long in education, we’ve been stuck in a system of trying to do things better. It hasn’t worked for 20 to 50 years. Why would it work now? So, we’ve got to do better things.”

Patrice Harding, a Head Start teacher in the Polk County school district, is one at least 2,600 public school district employees in Florida who are sending their children to private schools this year using school choice scholarships. Harding said she secured a choice scholarship for her daughter, Janelle, because she wanted a Christian education for Janelle and a school that would challenge her academically.

Many public school districts oppose private school choice, but in Florida, one of the most choice-rich states in America, many of their employees embrace it.

This school year, at least 2,600 public school district employees in Florida are sending their children to private schools using the state’s two main private school choice programs.

We know this because parents who apply for the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship and Family Empowerment Scholarship for low- and middle-income families list employers on scholarship applications. This year, the two programs are serving roughly 155,000 students.

(The programs are administered by Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog. And huge thanks to Benjamin Pax in the Step Up information technology department for compiling the spread sheets that allowed me to sort by employer.)

Enrollment alone doesn’t capture the full extent of demand.

By my count, 3,866 district employees applied for the scholarships. Some were ineligible. Others chose not to use them. But the fact that they applied shows an appreciation for these options.

Employer information isn’t available for parents using Florida’s other K-12 scholarships. If it was, we’d see even higher numbers. At last count, the McKay Scholarship for students with disabilities was serving 25,832 students this year. Meanwhile, the Family Empowerment Scholarship for students with unique abilities – formerly known as the Gardiner Scholarship – is serving 23,720 students.

(This year, the McKay Scholarship will be merged into the Family Empowerment Scholarship.)

We don’t have information about job titles. The means-tested scholarships historically were limited to low-income families, and for many years the average scholarship family’s income hovered around $25,000 a year.

With higher income thresholds now in place, it’s likely higher-paid district employees, including teachers, are a bigger part of the scholarship parent mix. (Average annual income for scholarship families this year is $37,939.)

Several surveys and analyses over the years have found public school teachers are more likely than the general public to enroll their children in private schools. (See here, here, here.)

In Florida, public school teachers who use private school choice are not hard to find. One of the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship parents who intervened in the 2014 lawsuit that sought to kill that scholarship program was a district teacher and union member. Last summer, a district teacher/scholarship parent joined Gov. Ron DeSantis when he signed legislation expanding the scholarship programs.

The fact that public school employees use private school choice is not necessarily a knock on districts. There are endless reasons why parents want options for their children.

Some district employees using scholarships are critical of public schools in general and/or their employers specifically. Others are complimentary.

Marie Echevarria and her son, Eddie Joe, at the 2021 signing ceremony for HB 7045, which expanded scholarship eligibility to more Florida families.

One teacher, a 22-year veteran in one of Florida’s biggest districts, said her district has “an excellent school system.” But she secured choice scholarships for her children because she wanted a Christian education for them. It’s “best for them, and best for us as a family,” she said. “It teaches them the values they need to live on an everyday basis.”

Marie Echevarria, the Orange County teacher who spoke at DeSantis’s bill signing, had similar reasons for securing a scholarship. She said in a reimaginED podcast that she chose a school for her son that was “very welcoming, very life-involving, very family-caring” and that reflected her and her son’s faith.

“As both a public school teacher and a parent,” she said at the bill signing, “I know that even the best schools may not be the right fit for every child.”

Patrice Harding, a Head Start teacher in the Polk County district, said she got a choice scholarship for her second grader, Janelle, because she wanted a Christian education and then some. “I need her to be in a school that’s going to challenge her,” she said.

Harding said many teachers in her district use choice scholarships. The only push back she got, she said, was from a fellow teacher whose child attends a charter school.

Interestingly, nearly 300 parents using means-tested scholarships this year work for public schools other than district schools. That includes 240 who work for charter schools and 38 who work for Florida Virtual School.

That’s not necessarily a knock on those schools, either.

It’s just more evidence that just about everybody wants options for their kids.

Students at Hadassah John’s school on the San Carlos Apache Reservation in Arizona participate in hands-on activities to spark curiosity. John opened the school to give families an alternative to their F-graded district public school.

I had the opportunity recently to visit a new, small private school on the San Carlos Apache Reservation in Arizona. The school illustrates an education trend that is providing a new avenue for addressing America’s largest achievement gap.

The United States has done very poorly by Native Americans, including but hardly limited to K-12 education. Starting in the late 19th century, a group of “Indian Schools” was established. Authorities forcibly separated families and attempted to forcibly assimilate students, even beating them for speaking their native language. In addition to being barbaric and illiberal, these and other federal efforts have left Native American students with the largest achievement gap in the country.

The opposite of foreigners creating schools and forcing children to attend them is to have the community create its own schools and give families the opportunity to enroll. Arizona’s suite of charter and private choice policies has been expanding these opportunities over the years, and there has been progress.

As the chart above shows, Arizona has been making greater academic progress across all student subgroups than the national average, including with Native American students. The challenges, however, remain daunting. Many reservation areas are rural and remote, making it difficult to launch and maintain charter schools. All Arizona racial/ethnic subgroups scored equal to or above the national average on eighth-grade math and reading in 2017 except Native American students. Despite the gains, these students have yet to catch up to their peers nationally, much less to those peers’ Anglo averages.

A new school on the Apache Nation, however, points to a new hope. A Democratic senator from Arizona’s Navajo Nation pushed legislation through years ago making residents of Arizona reservations eligible to receive an Empowerment Scholarship. In January 2019, a small group of these students began participating and created a new private school.

Hadassah John, the school’s teacher, attended Apache reservation schools. She became inspired to start a new school because public schools in the area were low-performing, and her students experienced bullying and a lack of academic challenge. The local school district spends well above the Arizona state average but earned a letter grade of F from the state. Parent reviews, and even a teacher review, on the Great Schools site are scathing. John felt the community needed an alternative.

“I believe a child cannot learn if, one, they do not feel safe; and two, if they are not understood. This alternative offers each child (a chance) to learn at their own pace. They do not have to feel insecure or inferior to the student sitting next to them,” John noted.

Students at John’s schools focus on hands-on projects. On the day of my tour, a visiting Stanford graduate student was assisting them with designing and printing 3-D objects. They obviously were having fun.

John, who runs the school from a church campus, has raised $5,000 to purchase supplies and technology. She hopes to add a second class of students in the fall, and despite many obstacles, may be on the forefront of a new teacher-led model of education.

In her words: “If there is no joy in what you do or believe, it is harder to carry with you. There are a lot of challenges I have faced since Day 1. I have used each challenge thrown at us as a brick to help build a bridge for students to cross from hopelessness over to success and education.”

When I shared with John that I recently heard a 44-year veteran teacher relate on a radio program that “the joy has been strangled out of the profession,” and that the problem in education is not a lack of money, she responded with a quote from Albert Einstein: “It is the supreme art of the teacher to awaken joy in creative expression and knowledge.”

From what I saw during my visit, it looks like joy is fully awake at this new school.