When “edupreneur” Amy Marotz, second from right, decided to launch Awakening Spirit Homeschool Collaborative on a 15-acre single-family home site outside of Stillwater, Minn., she looked beyond traditional teacher training colleges for guidance, turning instead to an organization in Pennsylvania that helps teachers build the schools of their dreams.

Editor’s note: This article is the third in a series that explores how today’s teachers are being prepared – or not – for the classroom now that education choice has become normalized. You can read the first two articles here and here.

When Amy Marotz wanted to start a private homeschool collaborative for children with sensory issues, she didn’t rely on a traditional college of education for training, even though she had a master’s degree from one.

Instead, the former English teacher turned to Microschool Builders, a startup based in Pennsylvania. The firm, founded in 2019 by veteran educator and administrator Mara Linaberger, offers an array of services to prepare those seeking to become school founders. Most of the clients are teachers who want to trade their jobs in traditional classrooms for more fulfilling work in education.

Marotz, who leads Awakening Spirt School in the Minnesota Twin Cities area, is not alone in her desire for better opportunities. A 2022 survey commissioned by the National Education Association revealed that 55% of educators who responded said they were more likely to leave or retire sooner than planned. Reasons cited were burnout, general stress from the pandemic, student absences, and unfilled job openings leading to heavier workloads.

A recent special report from Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog, and EdChoice, highlighted 10 Florida educators who left the traditional classroom to start alternative education models. Top reasons included frustration with public schools, a desire to create options that better served their own children, a desire to create options that better serve teachers.

As more state legislatures approve education choice scholarships that can fuel growth in this segment, traditional four-year universities have yet to develop training options for teachers who see the benefit of bypassing traditional schools in favor of establishing alterative models.

Though some have embraced innovation, it has been mainly within the framework of traditional school systems. Most notable among these are Arizona State University’s Next Education Workforce initiative, which seeks to recruit and retain traditional school teachers by redesigning the workplace.

In Tennessee, Austin Peay State University created a three-year program in partnership with school districts and community colleges to attract and retain non-traditional students to the profession. The program, which was adopted statewide, became the first federal apprenticeship model of its kind and a model for the nation.

Still, when it comes to equipping these “eduprenuers,” resources are limited to companies that cater to established teachers who are burned out on traditional schools and seeking the opportunities to reconnect them with the love for teaching that drew them to education in the first place.

“Any attention to education innovation or alternative learning models that exist outside of traditional schooling are typically marginalized in these programs, if they are addressed at all,” said Kerry McDonald, a senior education fellow at the Foundation for Economic Education and author of the 2019 book “Unschooled: Raising Curious, Well-Educated Children Outside the Conventional Classroom.”

“This has long been true, but is perhaps more apparent today as microschools, homeschooling, learning pods, and similar models become increasingly popular,” she said.

Why have traditional colleges of education ignored this group in favor of the public school system? No one knows for sure, but experts offered some ideas.

First, the old way is simpler and scalable. It’s easy to plug in, and most education professors were trained in the traditional school model.

“They’re not entrepreneurs for the most part. It’s just not part of their DNA,” said Eric Wearne, an associate professor in the Education Economics Center at Kennesaw State University in Georgia and the director of the university’s National Hybrid Schools Project. The initiative seeks to document and analyze the variety of independent actors who are creating new forms of K-12 schooling outside of the conventional education system.

Wearne called most programs “thinly veiled arms of the HR department of the school district,” which they depend on to provide internships for their majors. States also have certification rules for teachers and working with public school districts allow for easier compliance.

“They’ve got to place a ton of students every semester,” Wearne said. “They have incentives to work with the school system.”

Also, the variety and complexity of all the different non-traditional methods make training a challenge. If colleges wanted to offer such training, it would be best to let majors choose to specialize in a certain model and follow a track rather than create new programs that address all non-traditional forms together as all are unique.

For example, requiring training in classical education, which emphasizes memorization, would be a poor fit for someone who considers such memorization pointless, he explained. A school also could add certifications in certain specialties or offer courses in business entrepreneurship for those who want them.

He said the private companies may be best equipped to train those who feel called to leave the beaten path because “most of those (graduates) are going to working for public school systems or private schools that look functionally similar.”

Another challenge to traditional universities is that as states continue to approve education choice policies that allow innovation to increase and flourish, the role of the teacher is also quickly changing. The idea of who counts as a teacher has also been expanded, with some companies that specialize in self-directed learning using guides instead of certified educators.

In a recent report on the transformative effects of the pandemic on learning, the Center on Reinventing Public Education recommends that the traditional schools themselves should be the ones to change the way they have done education for decades to capitalize on the innovation that sprang up during the pandemic and incorporate a more bottom-up approach.

It recommends new models in which teams of teachers take on different responsibilities based on their strengths and interests rather than have one teacher in charge of 20 to 30 students all day. Such innovations might keep teachers in the profession and provide better learning opportunities for all students regardless of where they get their education, said Travis Pillow, innovation fellow and senior writer at the center.

“We have to start treating teachers as knowledge workers the same way we do doctors and lawyers,” he said.

Wearne said that should extend to teachers’ colleges. If they don’t find ways to adapt as demand for non-traditional options increase among students and teachers, enrollments could decline as startups fill the void.

“If you have a natural decline in enrollment and huge market demand, then choosing not to meet that need does bode well for long-term prospects,” he said.

The Early Learning Residency Program at Austin Peay University proved to be exactly what recent graduate Malachi Johnson was looking for when he graduated from high school: a college education and a guaranteed job. The day he received his diploma, he began his career as a teacher in Tennessee’s Clarkesville-Montgomery County School System.

In her 20s, Heather Fracker set her sights on becoming a respiratory therapist. But as John Lennon observed, “Life is what happens when you’re busy making other plans.”

Fast forward two decades, and Fracker, a 43-year-old single mom to two middle schoolers, is pursuing a new dream. In two years, she will be a fully credentialed elementary school teacher thanks to an accelerated program that began in her hometown.

“Never in a million years did I think I’d want to be a teacher,” Fracker said.

Heather Fracker, left, is working on a bachelor’s degree in education through Tennessee’s Early Learning Residency Program with help from her mentor, Belinda Cornell.

But subbing and volunteering in schools in her area changed her mind. She began working toward a childhood development associate credential to teach pre-kindergarten. Fracker did so well that the Tennessee Early Childhood Training Alliance, a statewide organization with locations at multiple colleges and universities, nominated her for the Early Learning Teacher Residency Program at Austin Peay State University, then in its third year.

“At first, I said no,” she said, “because my plan was already in place.”

But alliance leaders won her over by telling her it was a terrific opportunity, that she easily could add a pre-K endorsement by taking an exam. Now, Fracker is at the head of a third-grade classroom three days a week and working toward a bachelor’s degree in the evenings.

Going back to college in mid-life to pursue a new career can be prohibitive due to the cost and time commitment involved. But the Clarkesville-Montgomery County School System, and more recently, the state of Tennessee, are banking on individuals like Fracker who offer a solution to the teacher shortage and retention issues that have plagued the profession for years – a challenge that has become more severe as teachers leave traditional classrooms to start their own schools or choose not to teach in the first place.

In Tennessee, the “Grow Your Own” program started in 2018 as a partnership between the school system and Austin Peay, a public institution with 8,418 undergraduates.

Located about 12 miles south of the Kentucky state line and about an hour’s drive from Nashville, U.S. News & World Report ranked the university 41st out of 135 among regional colleges in the South.

The Clarksville-Montgomery County School System employs 2,550 teachers who are charged with delivering instruction to 37,900 students, half of whom are classified as economically disadvantaged. Almost 16% have disabilities, and 5% have a first language other than English.

Leaders at both organizations came up with the idea in response to shared concerns discovered during meetings aimed at improving their partnership. Chief among them: the critical teacher shortage.

“We both wanted to address the issue of the teacher shortage, of not having enough graduates in high needs areas, especially STEM, and we both wanted to add diverse students to our programs,” said Lisa Barron, associate dean of the Eriksson College of Education at Austin Peay.

The commiserating quickly turned to brainstorming.

“Once we really started getting serious about how we impact this, we realized that if we were to completely redesign teacher education, it probably would not look like what it does today,” Barron said.

For the program to be successful, the groups decided, several factors had to come together. It would have to attract individuals who were settled in their hometowns, preferably those already connected to schools, including volunteers, aides, custodians or bus drivers or others without college degrees.

They agreed the program needed to be free to students and that it must be flexible enough for them to work and support their families while they trained. Additionally, they agreed, the program had to move faster than the traditional four-year university route, and it had to provide support in the form of wrap-around services to help students navigate challenges.

Prentice Chandler

“We sometimes have made becoming a teacher harder than it has to be,” said Ericksson College dean Prentice Chandler. “I know a university is not the easiest place to navigate, and that’s our fault.”

Chandler dismisses the notion that no one wants to be a teacher these days, advancing the idea that the teacher shortage can be solved by removing barriers to well-designed programs. Chief among those barriers, Chandler believes, is what he sees as a lack of cooperation between teacher prep programs and school districts.

“We train teachers and we let them loose, and you hire them, and that’s it, we’re done,” he said. “The responsibility of preparation of teachers belongs to colleges of education working in tandem with their school partners. Without that sort of paradigm shift, I don’t think any of this work happens.”

In its first year, the Early Learning Teacher Residency Program accepted 20 recent high school graduates and 20 Clarksville-Montgomery County teachers’ aides. The model in place at that time is basically the same today.

Participants are employed throughout the program as teachers’ aides in classrooms led by the school system’s most experienced and highly effective teachers at elementary schools in lower-income areas. As employees, they receive a salary and benefits. The supervising teachers receive a stipend for each participant they mentor.

During their three-year residency, candidates must master all state-required competencies. They also must pass all state-required certification exams. After the final school bell rings each day, participants take classes toward a bachelor’s degree in education. They study year round with no summer break. All costs, including tuition, fees, textbooks, and anything else associated with the program, are covered.

Initially, participants were split between the university and the school system. That changed in 2021, when the state took notice of the program and expanded it by awarding $100,000 grants among 13 higher education providers across the state.

“It’s accelerated, but it’s not easy,” said Sean Impeartrice, chief academic officer for the Clarksville-Montgomery County School System. He stressed that graduates get the same quality of training as traditional education majors.

Since the program’s inception, Austin Peay has forged partnerships with community colleges, which offer two-year education degrees at no cost to students. After earning a two-year degree, the students take their remaining classes from the university.

Once program participants graduate, they must spend at least three years teaching in the school districts where they did their residency.

Program administrators say the wraparound support participants receive is key to ensuring they successfully complete their training.

“We work really hard to get rid of the many barriers that residents may have,” said Lavetta Radford, the education pipeline facilitator for the Clarksville-Montgomery County School System. “They may be academic, financial, or related to mental health. Sometimes life happens. We have residents who have lost children, who are taking care of aging parents, had surgery, or they may just need a space to come and work.”

For Fracker, the biggest challenge has been trying to spend time with her children. Now, most of her evenings are reserved for study. The course terms have been condensed from 12 weeks to seven weeks, so the workload is heavier.

“I have had to have many heart-to-heart talks,” she said. “They ask for a lot of time I can’t give. I have to keep reminding them that mommy is doing this to give them a better life.”

Her mentor, Belinda Cornell, is always there to offer Fracker everything from tutoring to a word of encouragement.

“She brings great classroom management skills,” said Cornell, a 38-year teacher who supervises two residents in addition to Fracker. “She has really knocked it out of the park … I’m there supporting her, but she’s taking the lead now.”

Soon after it began, the program began garnering state and national attention. The state of Tennessee has expanded it to 13 universities that partner with 65 school districts.

In January, Tennessee became the first state in the nation to be approved by the U.S. Department of Labor to establish a permanent Grow Your Own apprenticeship program, with the Teacher Residency program established by Austin Peay and Clarksville-Montgomery County as the first registered apprenticeship program.

“Tennessee’s leadership in expanding its Grow Your Own program is a model for states across the country that are working to address shortages in the educator workforce and expand the pipeline into the teaching profession,” U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona said in a news release.

Cardona pointed out that the program could not be more urgent or necessary as educators attempt to recoup COVID-19 learning loss.

Malachi Johnson toyed with the idea of becoming a teacher while a senior in high school but was nervous about paying college tuition for four years. In August, he was among the first class to graduate from the “Grow Your Own” teacher training program at Austin Peay State University.

More recently, the Tennessee Department of Education and the University of Tennessee System, comprised of university campuses throughout the state, announced plans to establish a $20 million Grow Your Own center to bolster the pipeline programs. The state also is working with the Council of Chief State School Officers to launch similar programs in other states.

Impeartrice, the school system’s chief academic officer, acknowledged that the program has not completely solved the teacher scarcity problem but said it has helped shrink the shortage. About 160 residents are now enrolled in the program.

“If we didn’t have the program, we’d be 150 teachers short rather than 50 teachers short,” he said. “We can close that gap. That’s doable.”

In August, the school system was able to at least narrow the gap as Austin Peay State University graduated its first class of newly minted residents, ready to serve as full-time teachers in the Clarksville-Montgomery County School System.

“It’s crazy because the night of graduation, I go to work for an open house so I can meet my students,” said Malachi Johnson, who was hired at a local elementary school. “I am jumping right into it and can’t wait.”

Fracker agrees. She expects she’ll feel more like a veteran than a newbie when she graduates with three years of teaching experience on which to draw, fully prepared to embark upon her new dream.

In the classic Krisis at Kamp Krusty episode of “The Simpsons,” Bart discovers that the summer camp he and Lisa attend is a de-facto child slave labor camp, prompting him to lead a rebellion and camp take over. Decades later, your author still laughs uncontrollably when recalling the “Lord of the Flies” reference in this clip from the episode.

In the classic Krisis at Kamp Krusty episode of “The Simpsons,” Bart discovers that the summer camp he and Lisa attend is a de-facto child slave labor camp, prompting him to lead a rebellion and camp take over. Decades later, your author still laughs uncontrollably when recalling the “Lord of the Flies” reference in this clip from the episode.

Far less laughable is the emergence of reports from teachers concerning post-pandemic-return student behavior. A recent survey of public-school teachers conducted by The 74, a nonpartisan education news group, related:

From regular f-bombs and bullying to difficulty finishing assignments, raising hands or buttoning pants, young people across the country are struggling to adjust to classrooms after lengthy pandemic isolation.

One hundred twenty-two teachers from 37 states and Washington, D.C., painted a picture of a generation emotionally anxious, academically confused and addicted to technology, in a survey created by The 74 … Educators from coast to coast noted students had difficulty with common classroom routines — writing down homework, raising their hands to speak, meeting deadlines. And for the youngest learners, underdeveloped motor skills made it difficult to use scissors, color, paint, and print letters.

Kathleen Casey-Kirschling

Kathleen Casey-Kirschling, pictured here, was born at midnight on January 1, 1946, making her the first American Baby Boomer. She worked as a public-school teacher and retired (ahem) 15 years ago. All of America’s massive cohort of Baby Boomers will have reached the age of 65 by 2030.

No problem. We’ll just recruit Millennials to replace them, right? Wrong.

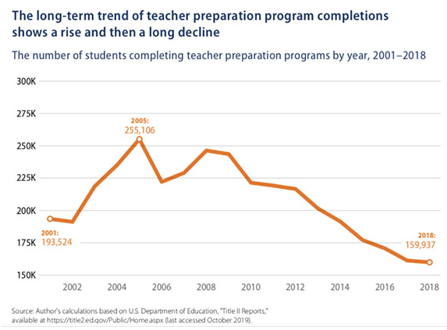

We saw declining success in the effort to replace Kathleen and her cohorts even before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Ante-pandemic, the percentage of college students enrolling in colleges of education began to fall. During and after, the absolute numbers of college students began to fall, so let’s call that a shrinking percentage of a shrinking pool.

Ante-pandemic, the percentage of college students enrolling in colleges of education began to fall. During and after, the absolute numbers of college students began to fall, so let’s call that a shrinking percentage of a shrinking pool.

Lord of the Flies seems likely to simply reinforce the desire of college students to major in something other than education. With this context in mind, your author got a good, long chuckle from the absurd hysterics of Arizona passing a law to allow public schools to pay student teachers.

Said Jacqueline Rodriguez, vice president of research, policy and advocacy at the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education:

“We have now allowed K-12 students to be placed in harm’s way with an unprepared person at the helm of the classroom by putting them in a position where they’re not only set up for failure, but it is very unlikely that they are retained in that same position, because they were not set up with the skills, knowledge, and dispositions to be successful.”

It is a tradition of long-standing to force student teachers to pay thousands of dollars and/or go further into debt while providing free labor to schools. This, however, strikes me as a tradition rather ill-suited to our current circumstances.

If districts could pay student teachers, it just might get more people to teach. Student teachers were going to be in schools whether this bill passed or not, but color me all in favor of not exploiting them.

In the end, such proposals work at the margins. The entire teaching profession must be reimagined to attract the talent necessary to allow teachers to teach and to provide the structure necessary for students to thrive.

Some states are moving forward with this, but for the rest, the beatings will continue until morale improves.

Editor’s note: Former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush advocates for teacher education reform to better improve the talent pipeline and encourage new educators in this opinion piece circulated by ExcelinEd, the organization for which he is founder and chairman. The commentary published originally in the Miami Herald.

Editor’s note: Former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush advocates for teacher education reform to better improve the talent pipeline and encourage new educators in this opinion piece circulated by ExcelinEd, the organization for which he is founder and chairman. The commentary published originally in the Miami Herald.

Across the country, schools are struggling to hire enough teachers, and long-term trends suggest the problem could get worse. A number of factors contribute to this shortage, and even prior to the pandemic, the number of young people enrolling in traditional teacher preparation programs has been in decline since 2010.

We owe it to our nation’s 61 million students to reimagine how we support our hardworking, professional educators.

Here in Florida, Gov. Ron DeSantis and the Legislature included $800 million for teacher pay raises, and while teacher pay is one important component to attracting and retaining talent, elected officials and education leaders nationwide need to do more. Another critical barrier is the teacher preparedness and licensing process.

Today’s model is largely outdated, and it’s costly. Those interested in being teachers are required to spend years in college classes, then take their certification exams, before entering the classroom with maybe a semester’s worth of on-the-job training.

This system is not setting up these educators or the students they’re expected to serve for success. It forces new teachers to start their careers with tens of thousands of dollars in debt and little hands-on experience. The system prioritizes seat time with a professor in a college classroom over hands-on training alongside an experienced educator in an actual classroom.

Burdensome teacher preparation also keeps the diversity of our teacher workforce from keeping pace with the growing diversity of the country’s population. Research has shown that teacher preparation programs are less likely to attract aspiring Black and Hispanic teachers, who are more likely to follow non-traditional paths into the profession.

In Florida, 36% of public-school students, but just 17% of teachers, are Hispanic. And more than 21% of students, but just 14% of teachers, are Black — and other states see similar disparities. Thankfully, some states are building a better way.

Last Tuesday, I had the privilege of talking with Penny Schwinn, the state education commissioner of Tennessee, which earlier this year became the first state in the nation with a federally approved teacher apprenticeship program. Tennessee’s innovative approach allows future teachers to work with students in a classroom, receive coaching from experienced mentor teachers and be paid along the way.

The program is designed to allow the future teachers to obtain a bachelor’s degree in three years, debt-free, while being paid, and enter the teaching profession with at least three years’ classroom experience under their belt. All of which is paid for by leveraging federal funding for apprenticeships.

Schwinn designed the program by taking into account the barriers that often keep new and talented educators from entering the field: Graduating college with debt and entering the field feeling unprepared. The program is even attracting career-switchers like Nahil Andujar, who left her job at a healthcare company after discovering she loved working with kids. As she told an education-focused media outlet: “I wasn’t planning to become a teacher, but I noticed how a teacher could transform a student’s life.”

School districts that participate in the apprenticeship program partner with a local college or university — with the goal to recruit future educators from within the community they’ll serve. Each resident teacher, while paired with a mentor, receives at least 6,000 on-the-job learning hours in the program.

Upon graduation, the resident teacher becomes fully state certified teacher and receives full-time employment, with the requirement that the new teacher provide at least three years of teaching services. Other states, like Texas, are designing similar “grow-your-own” teacher preparation programs. It’s easy to see why.

This new approach to attracting talented professionals to the teaching profession is vital to the success of students. Florida reports critical teacher shortages in core subjects like English, math and science, as well as critical specialty areas, like English as a second language and special education.

Teacher apprenticeships can be one part of an effort to address these gaps, and part of a broader and bolder strategy to reimagine America’s teaching profession — to build a sustainable, long-term solution to recruiting the highest qualified professionals into the teaching field. States should create as many diverse pathways into the teaching field as possible, investing in alternative certification programs that attract more diverse pool of talent than traditional preparation programs.

But they should also explore proven policies that redefine who can teach and what teaching looks like. Professionals in other fields, doctors, lawyers and accountants have a choice: They can work for large public institutions, like hospitals. Or they can go into private practice, serving clients or patients on their own terms.

Indiana is working on a first-in-the-nation policy that would allow teachers to do the same, while retaining their pay and benefits through the state. The new law, which is in its initial phase, would allow teachers to contract with parents to design learning environments around an individual student’s needs.

Another new law in Indiana is similar to a policy offered here in Florida and would allow districts to hire adjunct teachers — professionals from outside education who want to share their skills with students. A retired engineer could teach an algebra class. A professional builder could spend an hour a day helping high school students earn industry credentials in their trade.

As school systems grapple with teacher shortages, communities across this country are full of talented people who would love to make a career helping students learn. Just as the future of education rests on reimagining education around individual students, the future also relies on reforming the teaching profession to better improve the talent pipeline and empower new educators with diverse pathways to the classroom.

In this episode, Tuthill talks with the head of the leading platform for enabling educator advancement via micro-credentials, a form of micro-certification that supports, scales and grows effective teachers. Sanford Kenyon joined BloomBoard as chief revenue officer in 2015 after 25 years in software and technology-based businesses and assumed the role of chief executive officer in February 2017.

In this episode, Tuthill talks with the head of the leading platform for enabling educator advancement via micro-credentials, a form of micro-certification that supports, scales and grows effective teachers. Sanford Kenyon joined BloomBoard as chief revenue officer in 2015 after 25 years in software and technology-based businesses and assumed the role of chief executive officer in February 2017.

Unlike a traditional course or workshop where the learning process is linear and time-based, the micro-credential learning process is a unique online experience whereby educators gain an understanding at the outset of their specific goals, and then personalize their learning to achieve the specific requirements for achieving competence. BloomBoard, based in Palo Alto, California, offers competency-based professional learning programs to state and district leaders.

Kenyon’s discusses with Tuthill his view that COVID-19 has made every student in America a “blended modality” learner because they’ve been freed from the confines of a brick-and-mortar classroom. They also discuss the concept of micro-credentialing and how it allows teachers to improve student outcomes and increase equity. Both agree that a student-centered approach is the way to move public education out of the factory, one-size-fits-all model and into the future.

"COVID-19 has kicked open that door and shoved us through ... We have to have a set of practical skills and tools to help educators right now."

EPISODE DETAILS:

· The nuts and bolts of micro-credentialing

· The exponential change COVID-19 has wrought on public education

· How technology is critical for scaling a blended model for each individual student

· BloomBoard’s turnkey program for school districts to deploy to teachers

· The changing role of the teacher in a broader definition of public education

FCAT. FCAT writing scores up. FCAT reading and math scores flat. Miami Herald. South Florida Sun-Sentinel. Palm Beach Post. Orlando Sentinel. Florida Times Union. StateImpact Florida. Gainesville Sun. Ocala Star Banner. Associated Press. Naples Daily News. Bradenton Herald. Sarasota Herald Tribune. Pensacola News Journal. Tallahassee Democrat. Panama City News Herald. StateImpact has more from Education Commissioner Tony Bennett.

FCAT success. How a Tampa elementary magnet school got traction. Gradebook.

FCAT success. How a Tampa elementary magnet school got traction. Gradebook.

FCAT retakes. Daytona Beach News Journal.

Vals and sals. Backlash is growing to Hernando's decision to ban vals and sals. Gradebook.

Nerds. Spelling bee champ Nupur Lala of Tampa helped make nerdy cool. Associated Press.

Turnaround schools. Hillsborough is proactive about trying to spark them. Tampa Bay Times.

Teacher training. The Hechinger Report uses Florida to base a story about reformers' aims with teacher training and recruitment. (more…)