Editor’s note: redefinED is supporting National Autism Awareness Month each Saturday in April by reposting articles from our archives that celebrate those who champion the educational rights of children with autism. Today’s post, which originally appeared in June 2018, features a dedicated teacher who refused to give up on a child with profound autism.

By Livi Stanford

Abigail Maass never spoke. It was hard for her to connect with others. She grew impatient easily.

Her struggles mirrored those of children everywhere who grow up with profound autism.

This all changed when she met Trina Middleton, a teacher with Duval County Public Schools.

Middleton said she consistently encouraged Abigail and gave her many opportunities to do different activities. She also enrolled her in intensive Applied Behavioral Analysis therapy. ABA is a therapeutic approach that helps people with autism improve their communication, social and academic skills.

“It is just believing in her abilities and supporting her and celebrating with her,” she said.

Priscilla Maass, Abigail’s mother, said Middleton’s belief in her daughter made all the difference.

“She is patient but is firm and the kids react to that,” she said. “She can think outside the box. She can come up with different techniques.”

According to Maass, Abigail has grown substantially in the 10 years that she has worked with Middleton, who now serves as the education director of the Jacksonville School for Autism.

According to Maass, Abigail has grown substantially in the 10 years that she has worked with Middleton, who now serves as the education director of the Jacksonville School for Autism.

Now, Abigail, 12, can use some sign language to communicate, especially about her feelings. She uses her iPad more frequently as a communication device. She finds productive activities at her school, such as helping in the lunchroom. She is also now able to feed herself.

Maass said that in Middleton, Abigail has found an educator she trusts.

“She gets her out of her shell,” she said. “She does not get offended when Abigail will tell her to go. When she needs someone to rely on, Abigail tends to go toward Trina.”

Parents and administrators describe Middleton as dedicating her life to children with special needs. At the Jacksonville School for Autism, Middleton has been credited with expanding classroom programs and for developing a bridge program with the goal of helping transition students from JSA into typical learning environments.

“She is the voice of calm in the storm of Autism for our families and staff, and her presence simply makes everyone in our school program more confident in their capabilities,” said Michelle Dunham, JSA’s executive director. “A true testament to her strength as a leader can be seen in the relationships she maintains today with so many teachers she worked within both public school and JSA.”

Middleton began her career in 1993, teaching emotionally disturbed children in St. Johns County.

She took some time away from teaching to raise her own children. In 2003, she began teaching at Duval County Schools. After four years, she became a site coach for schools that have self-contained classes for students with autism.

That lasted until 2012, when massive budget cuts were made to the school budget.

Middleton said she could not look her parents in the eyes and tell them their children were getting all they needed. She felt the budget cuts fell disproportionately on special needs programs.

The cuts, implemented in 2011, affected classroom curriculum and supplies as well as direct services in speech/language and occupational therapies. They also affected training for staff who worked with children with autism in the classroom.

Student-to-teacher ratios rose, sometimes 5 to 1 in self-contained classrooms, Middleton said.

And she had other ideas about how to change education for students with special needs. She wanted more instructional flexibility than the public school allowed.

“Students’ self-regulation and communication needs to be the focus prior to the focus being on academic areas,” Middleton said.

After learning of the budget cuts, Middleton decided to change course. She took a job at the Jacksonville School of Autism, a nonprofit K-12 educational center for children ages 2-22 with Autism Spectrum Disorder — a neurological condition characterized by a wide range of symptoms that often include challenges with social skills, repetitive behavior, speech and communication.

Founded by Dunham and her husband, the school continues to thrive with 51 students and 50 therapists and classroom teachers. The school also implemented a vocational training program for older students to help them acquire skills to become gainfully employed.

Serving as educational director, Middleton said she is most proud of her ability to establish a strong collaborative relationship between the school’s classroom and clinical staff, tailoring instruction to overcome each student’s individual challenges.

She frequently brings the entire clinical and classroom teams together to discuss students’ needs and progress.

Asked what is the most important thing that educators must do when they teach those with autism, Middleton said it is essential to respect them as human beings with intellectual capacities that far exceed their ability to communicate.

Students like Abigail Maas can attest.

Each of Ana Garcia’s home education students has a personalized education plan, which she’s aligned with the state of Florida’s education standards. Garcia worked in public schools for 12 years as a middle school English teacher, curriculum specialist and school-level director for accountability and instruction.

The American film classic Aliens features a group of futuristic Marines who bite off more than they can chew when a distant colony they’re exploring turns out to be a lair of deadly space monsters. Private Hudson, played by the late, great Bill Paxton, melts down in a panic. Sigourney Weaver’s Ripley reminds him that a young girl they had rescued, Newt, had survived for weeks on the space station with no weapons and no training, prompting Hudson’s memorable question: “Why don’t you put her in charge?”

Well, why not indeed? As the film continues, it becomes increasingly clear that Newt was far savvier than any of the Marines, Hudson in particular.

redefinED author Ron Matus recently reported from Miami, a K-12 education frontier, on former public schoolteacher Ana Garcia. “Miss Ana” rediscovered her calling by providing a group of special needs students with the education they need – in her home. An educator with a special needs son, she realized the system wasn’t working well for her as a teacher or as a mother.

redefinED author Ron Matus recently reported from Miami, a K-12 education frontier, on former public schoolteacher Ana Garcia. “Miss Ana” rediscovered her calling by providing a group of special needs students with the education they need – in her home. An educator with a special needs son, she realized the system wasn’t working well for her as a teacher or as a mother.

Garcia is far from alone on either front.

She loved teaching in district schools. But over the course of a decade, her passion ebbed. Too many mandates. Too much violence. Too little help, in her view, for students with disabilities.

Her experience resounds throughout the research on public school teacher retention.

For years, teachers have cited working conditions as the primary reason for leaving the profession, outpacing compensation. Garcia didn’t lose her ability to serve children with disabilities, but she lost her willingness to operate in a broken and frustrating system. Her experience also is consistent with teacher shortage research. A universe of veteran teachers who love to teach have lost their willingness to function as a cog in a bureaucratic machine.

Garcia’s experience as the parent of a special needs child, sadly, also is not unique. Matus writes:

Frustrations began to mount for Garcia the mom, too.

In Pre-K, Kevin was happy and learning in his neighborhood school, in a class with five kids and two teachers. But for kindergarten, he was assigned to an inclusion class with 25 kids, one teacher and one “floating” teacher who toggled between multiple classrooms. Garcia said Kevin’s clothes weren’t being changed when he soiled himself. He wasn’t being fed.

Then Kevin began escaping from class and, somehow, running all the way to a parking lot before being stopped. The first time, Garcia was frightened. The second time, shocked. The third time, angry.

In 2014, after 12 years as a middle school English teacher, curriculum specialist and school-level director for accountability and instruction, Garcia called it quits.

An old expression holds that if you want something done right, you do it yourself. The Gardiner Scholarship has empowered Ana Garcia to educate not only her son, but other students as well.

Miss Ana is back, and this time, she’s the one in charge. Matus continues:

Off the grid, homeschoolers are DIYing into increasingly sophisticated co-ops and enrichment programs. Micro-schools, whether mini-chains or one-offs, are pushing the limits of what’s possible. In Florida, choice scholarships are giving a more diverse mix of parents the opportunity to go small or go home.

Garcia envisions a micro-school that can also serve home education students who want part-time services, combined with a center for Applied Behavioral Analysis. In the meantime, she’s the mutineer at the heart of her cluster, connected to a blooming constellation of other clusters.

A few months ago, I posed the question: How are Florida policymakers planning to provide the human and physical capital to deal with a large projected increase in the student population, Baby Boom teacher retirement and increased facility needs, and increased Medicaid and pension demands all at the same time. Is the plan to somehow money-whip potential public schoolteachers into actual public schoolteachers when the state lacks the money for whipping, and teacher exit surveys show other issues, some listed above, loom even larger than pay? If so, the state might need a new plan.

Florida, like every other state, can’t hire enough special education teachers for public schools, even as it spends $400 million on space for 14,500 children – which looks like about $27,500 per space by my Texas public school math. Garcia sounds like a fantastic special education teacher, and she teaches in her own home. Right about now, I’m hearing a psychic scream from a frightened person with somewhat reactionary K-12 policy preferences: “How are we going to hold her accountable?” Answer: Families will rate her online and other families with have access to the ratings. Elegant and delightfully lacking in bureaucracy.

Ana Garcia offers a solution that families need. Florida has many more potential solutions in the form of teachers who got fed up like Miss Ana. Why don’t you put her in charge by giving more families the ability to lure her back into education – this time as the leader of her own school?

Ana Garcia’s home education cluster includes a total of seven students, including five with autism who use the Gardiner Scholarship, an education savings account in Florida for students with special needs. Joining Garcia (at front left) on a field trip to Zoo Miami last month was, from left to right, her husband Daniel; her son Kevin, 9; her daughter Khloe, 7; Angelo, 6; and Briana, a paraprofessional.

MIAMI – “Guys! Choo-choo formation!” At Ana Garcia’s command, a loose knot of people near the turnstiles at Zoo Miami – three adults, five kids – lined up, put their hands on the back shoulders of the person in front of them, and merged into something less locomotive than caterpillar. Sixteen feet proceeded on a motley ramble. Crocodiles awaited in the Everglades section, along with plenty of carefully guided learning.

So it goes on the education frontier.

Over the next few hours, Garcia, a public-school teacher turned pioneer, subtly steered her students toward goals in their personalized education plans. Project-based learning for one. Ecology for another. Speech therapy for another. She put special focus on the three with autism, including her 9-year-old son, Kevin.

Those students, and two others not in attendance, benefit from a learning option that is revolutionary but under the radar: a state-funded education savings account. It’s ESAs that make Garcia’s home education cluster – and perhaps, someday, a never-ending array of other clusters – possible. Without them, the landscapers, Uber drivers and Dollar Tree clerks who’ve entrusted Garcia with the education of their children would be limited to schools that don’t work for their children.

Garcia knows what that’s like. She endured a nightmare school experience with Kevin before getting an ESA for students with special needs. She says it changed his life – and hers.

“Parents don’t have to fear any more that they only have one choice,” Garcia said.

Neither do teachers.

* * *

Ana Garcia has a little Mary Poppins about her, no-nonsense but upbeat, with a drive to stoke curiosity that borders on fantastic. Walt Disney is her hero. Some saw swamp; he saw magic kingdom. Garcia feels that about the landscape in education. Her great-grandmother was a teacher in Cuba. Her aunts were teachers. As a kid, her playroom was furnished with a blackboard and old textbooks, and her dolls were her class. Now when she switches into teacher mode, she decelerates her … rapid … fire … speech … until she’s sure her student is catching on.

Ana Garcia has a little Mary Poppins about her, no-nonsense but upbeat, with a drive to stoke curiosity that borders on fantastic. Walt Disney is her hero. Some saw swamp; he saw magic kingdom. Garcia feels that about the landscape in education. Her great-grandmother was a teacher in Cuba. Her aunts were teachers. As a kid, her playroom was furnished with a blackboard and old textbooks, and her dolls were her class. Now when she switches into teacher mode, she decelerates her … rapid … fire … speech … until she’s sure her student is catching on.

“My favorite thing to hear,” she said, “is, ‘Wow miss, no one has ever taught me the way you have, or explained things the way you do.’ “

Garcia loved teaching in district schools. But over the course of a decade, the passion ebbed. Too many mandates. Too much violence. Too little help, in her view, for students with disabilities.

Frustrations began to mount for Garcia the mom, too.

In Pre-K, Kevin was happy and learning in his neighborhood school, in a class with five kids and two teachers. But for kindergarten, he was assigned to an inclusion class with 25 kids, one teacher and one “floating” teacher who toggled between multiple classrooms. Garcia said Kevin’s clothes weren’t being changed when he soiled himself. He wasn’t being fed.

Then Kevin began escaping from class and, somehow, running all the way to a parking lot before being stopped. The first time, Garcia was frightened. The second time, shocked. The third time, angry.

In 2014, after 12 years as a middle school English teacher, curriculum specialist and school-level director for accountability and instruction, Garcia called it quits.

* * *

But this is a story about education in Florida. So that’s not where it ends.

Each of Ana Garcia’s home education students has a personalized education plan, which she’s aligned with the state of Florida’s education standards. Garcia worked in public schools for 12 years as a middle school English teacher, curriculum specialist and school-level director for accountability and instruction.

At the zoo, Garcia’s 11-year-old, Gabriella, took photos of black bears and gopher tortoises so she could create a brochure. Her 7-year-old, Khloe, immersed herself in geography. Kevin collected data from exhibit signs, focusing on adaptive traits like bioluminescence.

Garcia knows where each student stands with their learning plans, which she has aligned with Florida education standards. She nudged each towards their targets.

At the Gator Hole, she shifted attention to Angelo, who is 6 and mostly non-verbal. She pointed to a blue crayfish. “What is that Angelo?” she said.

“A crab,” he said.

Not quite, but close enough. And another step for a boy whose gentle face belies a kid once prone to fighting and biting.

Garcia left the district, but she didn’t leave teaching. She just joined the mutiny.

Her cluster isn’t quite sustainable yet, but education savings accounts gives her hope it can be. The main one in Florida (and biggest in the country) is the Gardiner Scholarship. Created by the Florida Legislature in 2014, it now serves 11,276 students with special needs such as autism and Down syndrome, with nearly 1,900 more on a waiting list. (It’s administered by nonprofits like Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog.) Each scholarship is worth about $10,000 a year, and parents can use it for a wide variety of programs and services, including tuition, therapies, tutors, technology, curriculum – whatever a la carte combination they think best.

Angelo’s mom, Vilma Moran, considered several schools. But all wanted to place him in self-contained special education classes where she didn’t think he’d learn. When Angelo started with Miss Ana, he wasn’t talking, didn’t seem to recognize his mom and dad, and showed no emotion.

Now, Angelo loves dinosaurs and laughs at funny videos. Now he greets people by name.

“When we go somewhere, like the zoo, he’ll say, ‘Let’s go see the elephants,’ ” said Moran, who installs fences for a living. “He wasn’t like that two years ago.”

* * *

Kevin is terrified of thunder.

But as Garcia described in The 74, she used the ESA to ease his anxiety – and learn science in the process.

She worked with Kevin’s therapists and tutor to develop lesson plans around the subject of thunder and lightning. The therapists showed him pictures and videos of lightning, taught him calming techniques, and worked with him on articulating why he was scared. The tutor taught him how clouds form and what causes thunder. Knowledge reduced his fear.

“Sometimes, things need to be micro,” Garcia said. In a school district, “you can’t possibly tailor everything to every child. There needs to be a middle ground somewhere. There needs to be a hybrid.”

Or lots of hybrids.

Off the grid, homeschoolers are DIYing into increasingly sophisticated co-ops and enrichment programs. Micro-schools, whether mini-chains or one-offs, are pushing the limits of what’s possible. In Florida, choice scholarships are giving a more diverse mix of parents the opportunity to go small or go home.

Garcia envisions a micro-school that can also serve home education students who want part-time services, combined with a center for Applied Behavioral Analysis. In the meantime, she’s the mutineer at the heart of her cluster, connected to a blooming constellation of other clusters.

For example, a paraprofessional, training to becoming a registered behavioral therapist, joined Garcia and Garcia’s husband on the zoo trip. The five autistic students in Garcia’s orbit all go to the same ABA center, but each is served by different speech, occupational and physical therapists. Kevin has his own tutor, a certified teacher who executes a plan Garcia designed. But the tutor also works with other students in other settings. Once education is de-coupled from school, the potential matches of students and teachers becomes infinite.

Garcia arranged swimming lessons at the Y for some of her students, biscuit-making at Red Lobster for others. Music and martial arts classes are on tap, along with lessons in table manners at Cracker Barrel.

So it goes on the frontier.

* * *

The Miami-Dade school district has 350,456 students, counting 68,487 in charter schools. Throw in private schools, and Miami-Dade has 425,000 students. Competition between sectors may be the most intense in America. And if test scores and grad rates are any indication, students are benefitting.

But none of those schools, so good for so many, were good for Kevin and Angelo. Garcia’s micro-cluster is.

Will it last? Garcia thinks it can work financially with a few more students. But it’s complicated on the edge, and there is no trail. She said she’ll keep pressing to figure it out, and more pioneers every day will do the same.

“If it’s not me,” she said, “it’ll be somebody else.”

BBI International micro school is another example of what's possible with expansion of private school choice. Sixteen of its 50 students in K-5 use state-supported school choice scholarships. Here, first- and second-graders in Alexa Altamura's cooking class learn how to make bucatini with amatriciana -- and so much more.

POMPANO BEACH, Fla. – With a little help from their culinary instructor, the multi-ethnic group of first- and second-graders at BB International School chop, grate, dice, squeeze, season, stir and serve. They tong noodles into bubbling red sauce. They sprinkle in chili flakes. And along the way, they learn far more than how to rock an impressive bucatini with amatriciana.

The instructor, Alexa Altamura, adds a dash of math (slice the onion into cubes), a drop of geography (the pink salt is from the Himalayas), a pinch of global trade (tomatoes are originally from Mexico). She folds in a smidgen of anatomy (the role of muscles in chopping), a morsel of chemistry (steam, reduction, the Maillard reaction), a hint of marketing (that stamp in the cheese wax isn’t there by accident). There’s a little history scattered in (the recipe calls for pancetta because ancient Italians used cows for work, not food). And, incredibly, a lick of biology (a pivot into pasta varieties yields mention of black pasta, colored by the ink that squid disperse to escape predators.)

“There are more than 100 types of pasta,” Altamura tells her students, noses inhaling hot-plate heaven. “In America, we’re stifled.”

The cooking lesson at BBI is so fun, it’s easy to miss something even more fantastic: a peek into the future of public education.

BBI is a micro-school. In K-5, it has 50 students. (Its pre-school has another 80). The public school district around it has 271,000 students.

It’s wild to think of BBI as representative of tiny, new species emerging where Big and Standard have ruled for so long. But expansion of educational choice is shifting the terrain. The little ones, in all their nimble glory – from micro schools, to home school co-ops, to in between things that don’t even have names yet – have more ability than ever to adapt, evolve, expand. More educators can create options. More parents can choose them. And the potential niches where the twain shall meet are infinitely diverse.

“We could be a tony private school,” said Julia Musella, BBI’s founder and head of school. “But we make a deliberate effort to keep it affordable. This is a community school.”

Julia Musella wanted a high-quality, intentionally diverse school that emphasized how to learn, not what. BBI is the result of more than two decades of picking and choosing the best from a wide range of educational approaches. (Photo courtesy of Musella family.)

The child of a grocery store executive is enrolled here. So is the child of a cashier at Lester’s Diner. Trying to further describe BBI is like trying to describe a new color. Julia Musella and her son Luciano don’t have traditional educator backgrounds. Their vision, though, is an intentional blend of educational approaches they combined to spur curiosity and creativity. BBI, Julia Musella says, is “a world school with a Renaissance curriculum.”

School choice is key.

Sixteen of BBI’s K-5 students use educational choice scholarships. Ten use the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship for lower-income students. Five use McKay Scholarships for students with exceptionalities. One uses a Gardiner Scholarship, an education savings account for students with special needs such as autism. (Step Up For Students, which publishes this blog, administers the tax credit and Gardiner programs.) For some students, the Musella family foundation helps bridge the gap between scholarship and tuition.

The Musellas see choice as vital to advancing equity and diversity. Without it, BBI could not be the Renaissance-for-all they want it to be.

“In my area, there isn’t enough representation of what America is in our schools,” Julia Musella said, referring to diversity in schools, public and private. “You have to learn as a human being to work with everybody who lives on our planet. You have to understand them, and understand cultural differences, and find out what you have in common, and work from there.”

***

As fate would have it, BBI’s one-acre campus bloomed in the iguana-happy sprawl of Broward County. The centerpiece is the restored home of Pompano Beach’s founding family. Yellow brick, lush vegetation, rows of tricycles. The first impression, elegant and whimsical, is not by accident. (more…)

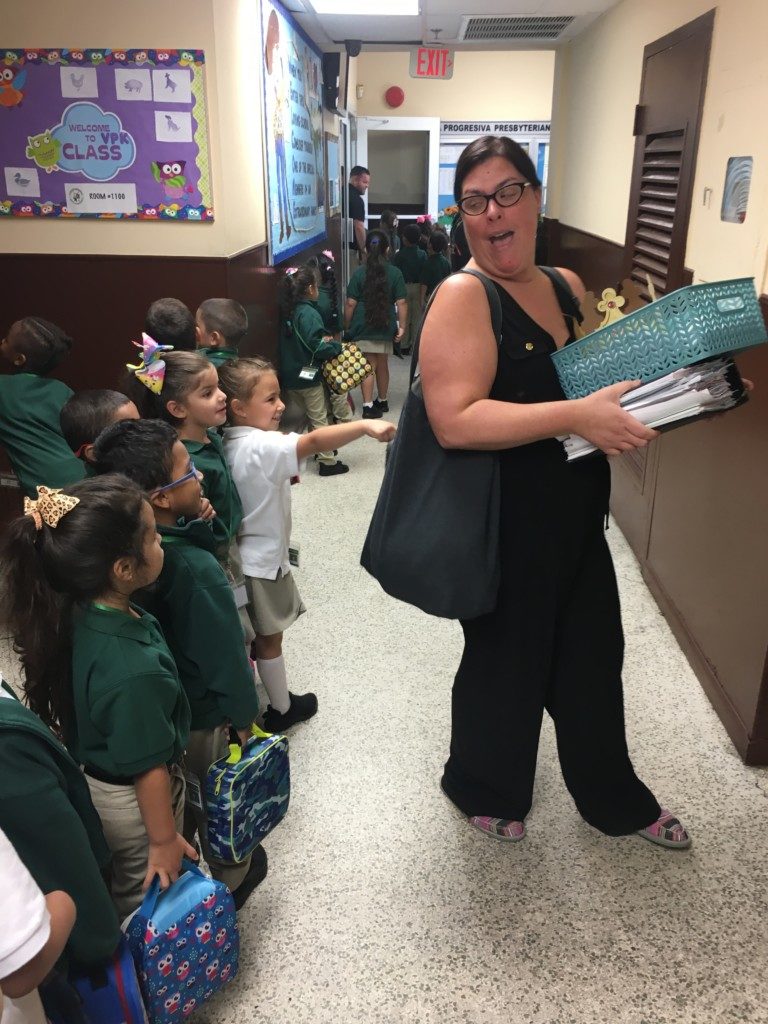

Melissa Rego, principal of La Progresiva Presbyterian School in Miami, has 18 years of experience in district, charter and private schools. When she assumed the helm of La Progresiva a decade ago, it had 162 students in K-12. Now it has 673-- all of them with school choice scholarships.

MIAMI – Little Havana is in a hurry. Long before dawn bathes the palms in soft light, thousands of workers stream from neighborhoods where modest homes are tucked in tight as pastelitos in a Cuban bakery. Ignition. Traction. Acceleration. Past the store fronts with the proud Latin names. Past used car lots studded with American flags. Past the restaurant walk-up windows where smooth, sweet cortaditos pump fuel into true believers.

In the thick of this working-class hum is a faith-based school once harassed by Fidel Castro. He couldn’t kill La Progresiva Presybterian. Neither could the teachers union. Now it’s thriving more than ever.

How fitting that it’s led by a former public school teacher who’s the daughter of exiles.

How fitting that it’s led by a former public school teacher who’s the daughter of exiles.

Melissa Rego grew up four blocks from La Progresiva, the second child of a bank teller and a car mechanic. When she became principal a decade ago, the school with vanilla paint and Cuban roots had 162 students in K-12. Now it has 673 – all with state-backed school choice scholarships for lower-income students.*

The director who hired Rego told her to do whatever it takes to propel the school to its potential. So the woman with 1,000 facial gestures behind horn-rimmed glasses became Inspirer-in-Chief. Over and over, she reminds the sons and daughters of cooks and waitresses and gas station attendants what Little Havana teaches them every day. They know it in their bones, but still can’t hear it enough from somebody who’s been-there-done-that.

“More than anything, it was speaking life into these kids,” Rego said. “Battling with these kids about the thoughts they have, that they can’t accomplish anything. We told them, ‘You have the ability to do this. We’re going to equip you. You have a future. But you have to grind. You have to work like a dog. Things are not going to fall out of the sky for you.’ ”

Florida is home to arguably the most diverse array of school choice in America. The pluses for students and parents are well established. But choice is helping educators, too. More and more (see here, here, here, here) are able to work in, lead, and even create educational options that are in line with their talents, visions and values. In a world where choice is still “controversial,” they are trail blazers.

Rego, 42, didn’t set out to be one. She graduated from public school in Miami, got a full ride to Miami-Dade College, earned a bachelor’s in health science from the University of Miami. (Later, she earned a master’s in educational leadership from Nova Southeastern.) Her teaching career began 18 years ago. She started as a sub in the Miami-Dade district, working with emotionally disturbed students, then taught four years at a career academy high school. At the invitation of a friend who had become a principal, she headed to a new charter school.

The charter was serving 600 middle school students … in a movie theater. Its intended building wasn’t completed on time, so the school had to wing it.

That it did, successfully, helped Rego understand the power of school choice. (more…)

Kim Kuruzovich, an educator with more than 20 years experience in public, private and home schools, is executive director of LiFT Academy, a private school for students with special needs. Of 130 students, 124 attend with help from state-supported school choice scholarships.

SEMINOLE, Fla. – Kim Kuruzovich’s daughter Gina has moderate autism, speech apraxia and dyslexic tendencies. She began a suite of therapies at age 2, then, at age 4, saw a psychologist for an educational evaluation.

The expert wasn’t encouraging.

“He told us, ‘You can look forward to Gina putting pencils in a box,’ ” recalled Kuruzovich, who has more than 20 years of experience teaching students with disabilities.

She and husband Mike drove home in stunned silence. It took a couple of months, but they snapped out of the haze and chose to ignore that doctor. It was the start of Kuruzovich learning to trust her instincts as a parent as much as she trusted her instincts as an educator.

Now, 19 years later, Kuruzovich is executive director of a private school built on those instincts.

LiFT, which stands for Learning Independence for Tomorrow, opened in 2013 with 17 students and five unpaid teachers who wore every hat imaginable. Today, it operates on two spacious, tree-lined church campuses. They serve more than 130 students with special needs, 124 of whom attend thanks to state-supported school choice scholarships.

“I never, ever wanted to go into administration. Ever,” Kuruzovich said. “I only ever wanted to be a teacher. I love teaching. I love seeing the kid get it and feel good about themselves.”

“What I found is I still get it as an administrator, but I get it in a bigger way. Now it’s not just my classroom, it’s every kid in this school.”

Before LiFT, Kuruzovich had taught in public, private and home schools. Her passion and talents helped make LiFT possible.

So did school choice.

Three state-supported scholarships - the McKay Scholarship, a voucher for students with disabilities; the Gardiner Scholarship, an education savings account for students with special needs such as autism; and the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship for low-income and working-class students - allow many LiFT parents to access a school they wouldn’t have been able to afford otherwise. (The Gardiner and FTC scholarships are administered by nonprofits such as Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog.) But those scholarships also opened doors for Kuruzovich and her colleagues. It gave them power to create a school that could best serve those parents – and sync with their own visions of what a school should be.

In Florida, where school choice is becoming mainstream, more and more educators like Kuruzovich are walking through those doors.

***

It’s the first week of the school year, and Kuruzovich is in peak form – gliding through hallways and classrooms, a fast-talking, wise-cracking, blond blur of smiles and warmth.

The sheer number of inside jokes she shares with her students highlights how deep her connection runs with each of them. (more…)

MCINTOSH, Fla. - In the summer of 2014, Joelene Vining took the leap to become a charter school principal.

It may have been a risky move. She left a position as an assistant principal in neighboring Levy County to become head of the McIntosh Area School, a small elementary that's the pride of a hamlet northwest of Ocala.

The school was rated an F by the state. If it didn't raise its grade quickly, it would have been forced to close.

Vining started recruiting teachers to make the jump with her.

When the call came, Cindy Roach was sitting on the beach. She was a 30-year veteran educator, enjoying retirement. There was a chance she might return to the profession, but only under the right conditions. She would help all her students meet the state's academic standards, but she wouldn't be a slave to lesson scripts or mandatory pacing calendars. She would welcome support from administrators, but she didn't want them looking over her shoulder, questioning her every decision.

In exchange, Roach offered a guarantee: "By the end of the year [my students] would pass every assessment, and if they didn't, she could let me go." (more…)When the government no longer assigns every child to a school, and multiple options are available, how do parents choose among them? It's an under-explored question. Researchers are only beginning to understand what parents' preferences really are in choice-heavy states like Florida, or what the school choice experience looks like in cities like New Orleans where charter schools predominate and vouchers are also available.

For that reason, it's worth learning more about how sophisticated parents — specifically, those who happen to be teachers — vet school options for their own kids. The Association of American Educators recently posed that question to its members, and the results are one of the more interesting nuggets in the annual member survey it recently released.

AAE is a professional service organization for teachers, and an alternative to unions. Its members tend to be more supportive of school choice, with 38 percent saying they personally benefit from it and 79 percent saying they back charter schools — stronger support than Education Next found among teachers in its most recent poll.

Editor's note: This article originally ran in Education Week. Tuthill is the president of Step Up For Students, which co-hosts this blog.

With her recent passing, Marva Collins is being remembered for her glorious educational crusade to turn around the lives of low-income black children in Chicago. It's also worth remembering how she chose to do this. She cashed in her teacher-pension savings in the 1970s to start her own private school. With it, she combined a no-excuses attitude with high standards, strict discipline, and love—and got amazing results with limited resources.

In other words, Collins was empowered by school choice.

Twenty-five years after Milwaukee put private school vouchers on the map, a majority of states now have some form of private school choice. Just this year, Arkansas created its first voucher program, and Indiana expanded its voucher and tax-credit-scholarship programs. Five states either created or expanded education savings accounts, including Florida, which tripled funding for its program; and Nevada, which spawned the nation's most inclusive program, available to more than 90 percent of its students.

Twenty-five years after Milwaukee put private school vouchers on the map, a majority of states now have some form of private school choice. Just this year, Arkansas created its first voucher program, and Indiana expanded its voucher and tax-credit-scholarship programs. Five states either created or expanded education savings accounts, including Florida, which tripled funding for its program; and Nevada, which spawned the nation's most inclusive program, available to more than 90 percent of its students.

These opportunities are created, first and foremost, to give parents the power to choose the educational options that are best for their children. But teachers benefit as well, even if the story lines seldom mention them.

As choice expands, teachers will see more opportunities to create and/or work in educational models that hew to their vision and values, maximize their expertise, and result in better outcomes for students. Increasingly, they'll be able to bypass the red tape and micromanagement that plague too many district schools and serve students who are not finding success. In short, they'll be able to better shape their destinies, and the destinies of their students. (more…)

School choice. School choice can empower educators, Doug Tuthill writes in Education Week. He is the president of Step Up For Students, which co-hosts this blog and employs the author of this post.

School choice. School choice can empower educators, Doug Tuthill writes in Education Week. He is the president of Step Up For Students, which co-hosts this blog and employs the author of this post.

Charter schools. A new debate will track who runs charters. StateImpact.

Testing. The St. Johns school district cuts back on district assessments. St. Augustine Record.

Budgets. The Hillsborough school district has been plugging its budget with reserves, drawing concerns from credit ratings agencies. Tampa Bay Times. Tampa Tribune. The Sarasota Herald-Tribune highlights recent funding cuts to a program for adults with disabilities.

Teacher pay. The Santa Rosa school district and its union remain deadlocked over raises. Pensacola News-Journal.

Campaigns. Leon County Schools Superintendent Jackie Pons kicks off a contest re-election bid. Tallahassee Democrat.

Entrepreneurship. Collier high schools will offer business classes. Naples Daily News.

Technology. Comcast offers low-cost broadband service to low-income students. Palm Beach Post. (more…)