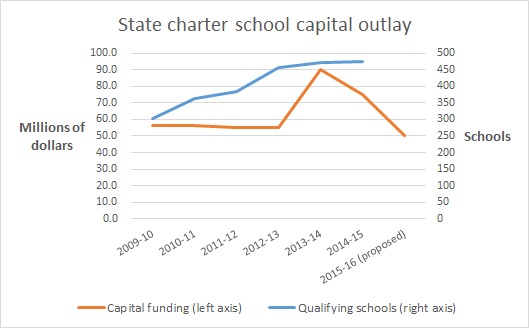

Florida’s charter schools are growing, but state funding that supports their facilities continues to shrink. The budget signed this morning by Gov. Rick Scott will reduce the state’s charter school capital outlay by a third, adding financial strain for hundreds of schools that rely on state funding to pay for buildings.

During the 2014-15 school year, school districts raised more than $2 billion in property tax revenue to cover capital costs. Since charters do not share that money in the vast majority of school districts, they rely on the state’s school construction fund, which provided $75 million to about three-fourths of the state’s nearly 650 charter schools during the fiscal year that ends next week.

Next year’s budget, which takes effect July 1, reduces that funding to $50 million.

Tim Kitts, who helped found the Bay Haven charter schools in North Florida, said the reduction leaves the network’s schools with less funding to pay their mortgages. The bills still need to be paid, so charters would likely need to dip into their operating budgets, he said.

As a result, in the coming year, the funding gap between charter schools and district schools will continue to widen.

In recent years, the state fund that helps pay for educational facilities has dwindled. Charters compete for scarce funds with colleges, universities and rural school districts. Other school districts also receive money through the state’s Public Education Capital Outlay, but unlike most charters, they have other revenue at their disposal.

This year, property taxes alone provided school districts an average of more than $860 per student in revenue. That figure includes students in charter schools, which generally don’t receive those funds. State funding, optional sales taxes, impact fees charged to developers, and other local funding sources provided some districts with tens of millions more.

In contrast, the nearly 480 charters that qualified for state facilities funding received about $312 per elementary school student and $466 per high school student, on average. Factor in the charters that don’t receive any facilities funding, and the numbers get even lower.

With charters’ funding reduced and property values expected to rise, the gap will almost certainly grow in the coming year.

“You have a significant inequity between between public school students,” said state Sen. John Legg, R-Trinity, who chairs the education committee. “The school districts and the charter schools need to come up with a model for equity.”

State lawmakers tried to address the gap this year, pursuing ideas that would have allowed charter schools to share districts’ property tax revenues. Those proposals ultimately faltered amid stiff opposition from school districts, which are starting to grow again, and are facing new construction costs.

Legg said that to break the deadlock, charter schools are going to have to make concessions of their own.

If school districts are going to share local facilities revenue with charter schools, they should have assurances that the buildings they fund will remain in public hands, Legg said. Charters shouldn’t be able to turn around and sell buildings that have been paid for with public money.

He helped found a Pasco County charter school that is subject to such a stipulation. If the school ever closed, its building would remain a public asset, which could house another school.

Charter schools should also be willing to communicate with districts about their growth plans, he said.

There are other debates to be had about what true equity would look like. For example, charters have more flexibility under the state’s building code, which means they might have lower construction costs than districts.

The fight for facilities for charter schools has led to pitched battled in other states. A group of parents and charter supporters in New York last month got the go-ahead to proceed with a lawsuit that claims it’s unfair to deny them equitable funding for facilities.

If charter school facilities funding continues to erode, the issue could come to a head in Florida.