Every so often, someone active in the curriculum reform movement will get frustrated and take time out of his or her schedule to denounce the school choice movement.

These folks tend to make obscure statements about “governance” or “structural” reform along the way to building a case that they have the one true faith that can improve education for all children. And they can produce a tremendous amount of evidence to support their curricular preferences.

Curriculum does matter. This reform tribe, however, apparently lacks a broad appreciation for politics and the mechanisms by which their preferences were largely driven out of the K-12 system.

John Chubb and Terry Moe explained back in 1990, and it bears frequent repeating, that the main problem with American K-12 is politics. Chubb and Moe did not use this exact terminology, but the American system of district schooling is very prone to the phenomenon of regulatory capture. This is the same phenomenon that leads state regulatory boards on banking, cosmetology, chiropractors or (fill in the blank here) to be quickly dominated by bankers, hair stylists and chiropractors or (fill in the blank here again).

The diffuse public interest is not organized. Your interest in state chiropractor policy is not something you think about, but it is something of intense interest to practitioners in the industry. Thus, through the normal and predictable workings of politics, such boards, intended to regulate industries they oversee, tend to be “captured” by special interests.

American school boards are elected. A certain brand of K-12 traditionalist will even sing the praises of local democracy in schooling. School board elections, however, are very vulnerable to regulatory capture. Single-digit turnout rates in school board elections happen routinely. Elections typically are non-partisan and low-profile. Highly motivated special interests such as unionized employees and major private contractors don’t find it dauntingly difficult to field working majorities on school boards.

Contractors make money building things and providing goods and services for districts. They aren’t likely to have strong preferences on curriculum. The same can’t be said for the unions. Their preferences, along with a large majority of college of education faculty, seem either actively or passively opposed to the preferences of curriculum reformers. Evidence has piled up that some forms of teaching reading and other subjects are more effective than others, and that disadvantaged children have been the primary victims of poor pedagogy for decades.

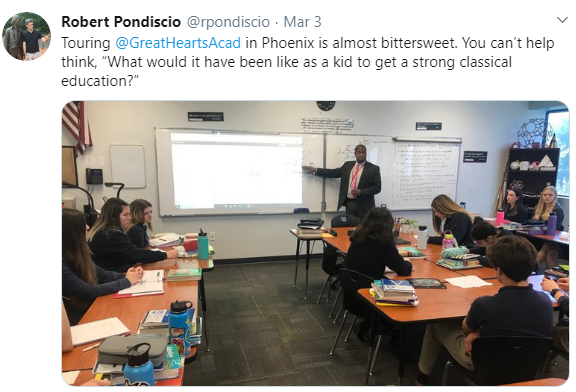

Curriculum reformers should support choice mechanisms such as charter schools and private choice programs because they create the opportunity for educators with minority viewpoints (think Core Knowledge fans) to create schools fulfilling their education vision. For instance, when Robert Pondiscio toured a Phoenix charter school recently, he tweeted:

Sometimes at this point in the conversation, curriculum reformers will raise the objection that focusing on choice means ignoring the district schools where most students attend. Nothing could be further from the truth. Back in 2013, this same classical education-focused charter group announced that it planned to open a school in my neighborhood. The image that introduces this post is a photo I took of my zoned district middle school’s response.

Giving educators and families the power to create a demand-driven system of schooling isn’t just a path to improving curriculum; so far as I can tell, it is the most effective path. Classical education is flourishing in Arizona and elsewhere because parents want it for their children and educators are willing to move heaven and earth to provide it to them.

Choice creates an incentive for districts to give parents the education they want. So curriculum reformers can either continue to bang their heads against the wall waiting for a future when they get to be the ones in control of curriculum, or they can go about the hard work of creating schools, revealing demand and making progress.

One of these strategies has a future; the other does not.