When it comes to education, expectations matter.

Not only will high expectations result in more students earning college degrees; expectations also make students less likely to experience teen pregnancies and to rely on public assistance programs, according to a recent study commissioned by the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, a national think tank committed to education choice and academic rigor.

According to the study, charter and private schools do the best job at conveying the message that high achievement should be the norm rather than the exception.

“High expectations are a good thing,” Seth Gershenson, a professor of public policy at American University and the author of the report, told Education Week. “Not only are they a good thing, but charter schools have more of a good thing.”

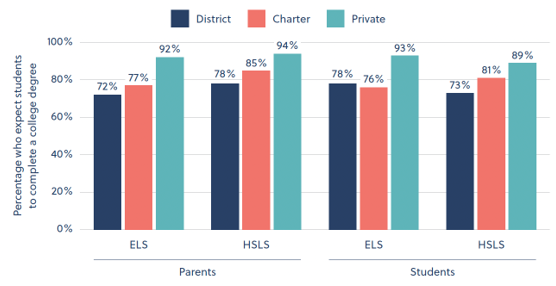

Gershenson, who is well known for his work on teacher expectations, used federal data from two nationally representative surveys to explore the links between high school teachers’ expectations of their students, specifically whether they would earn college degrees, students’ perceptions of their teachers’ expectations, and students’ long-term outcomes.

Among the findings:

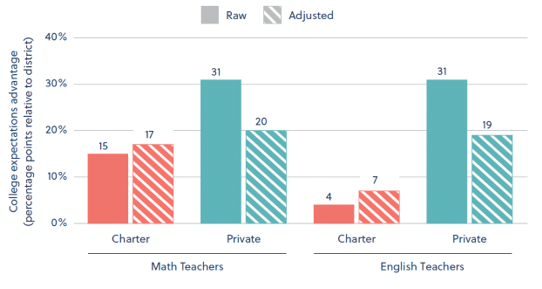

- In general, teachers in charter and private high schools are more likely to believe that their students will complete four-year college degrees.

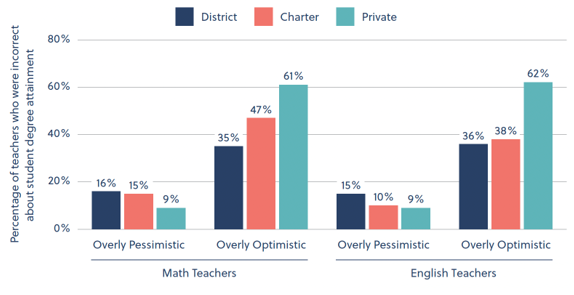

- In hindsight, teachers in charter and private schools were also more likely to overestimate students’ actual degree attainment.

- In general, students in charter and private schools are more likely to believe that their teachers think “all students can be successful.”

- Regardless of sector, teacher expectations have a positive impact on long-run outcomes, including boosting the odds of college completion and reducing the chances of teen pregnancy and receiving public assistance.

The data Gershenson used for his study came from the federal 2002 Educational Longitudinal Study and the 2009 High School Longitudinal Study. Both studies followed groups of 10th graders over time. The Educational Longitudinal Study followed up the students four and 10 years after the initial survey and had two teachers assess each student to answer the question, “How far do you think this student will get?”

The other study included a question about students’ assessments of their teachers’ general expectations for students in the school. Specifically, ninth graders were asked to what extent they agreed with the statement, “Your math teacher thinks all students can be successful.”

The two studies included 15,000 students. However, only 500 charter school students were included, which the author cites as a limitation of the study. The study controlled for a host of factors, including student race and sex, whether they received special education services, family income, the mother’s educational attainment, language spoken at home and standardized math scores at the end of ninth grade.

After adjusting for characteristics of students and schools, the study found that the private school advantage over traditional public schools had decreased by about a third, which the author attributed to household income disparities. However, the gap between charter school and traditional public school teachers’ expectations increased after those adjustments.

However, the findings showed that charter and private school teachers were also more likely than traditional public-school teachers to be overly optimistic about their students’ likelihood of success.

However, the findings showed that charter and private school teachers were also more likely than traditional public-school teachers to be overly optimistic about their students’ likelihood of success.

Still, Fordham analysts Amber Northern and David Griffith said that high expectations don’t harm students while low expectations do. All students need teachers who expect great things from then, and behave accordingly, they said.

They said this study takes on extra significance following the pandemic, which resulted in some schools lowering standards such as the requirement that students must be proficient in reading by the end of third grade to be promoted to fourth grade as well as softening grading policies. Even some colleges have lowered standards and are forgoing grades for first-year students, the report said.

Their recommendations included the following:

More families should have the option of enrolling their children in charter and private schools where high expectations are a core principle.

“Imagine, for a moment, that the teachers of a child you cared for didn’t believe in their gut that he or she was ‘college material’ or were otherwise skeptical of his or her potential,” Northern and Griffith wrote. “Wouldn’t you be looking for an alternative? Shouldn’t it be your right to demand one?”

Schools should not use students’ continuing challenges as justification for lowering expectations in the wake of the pandemic.

“Perhaps it’s unfair to second-guess those pandemic-induced changes,” Northern and Griffith continue. “But if we’re serious about getting our students back on track, we must be even more serious about getting our expectations for them back on track. Muttering the phrase ‘high expectations for all students’ just doesn’t cut it.”