Enter Central Florida’s Brighton Indian Reservation, past cattle fields and citrus groves, and it doesn’t take long to understand the priorities of this Florida Seminole Indian Tribe.

There’s a casino, but there’s also a new elder affairs building and a star-shaped veterans center ringed with giant bronze statues. And there’s a charter school that’s become the community’s heartbeat.

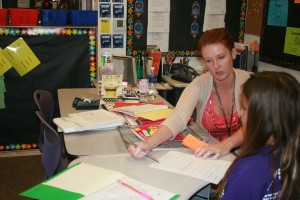

Inside Pemayetv Emahakv, which means “Our Way,’’ students in kindergarten through eighth grade straddle two worlds – one rooted in their rich, proud heritage; the other in the wider space where they must compete and succeed like their counterparts across the planet.

So they study Creek, the tribe’s native tongue, along with the state’s new science standards. They string Indian beads into necklaces and read books on Kindles. They cook fry bread in chickees and take standardized tests in state-of-the art classrooms.

“We wanted a native curriculum,’’ said Michele Thomas, a parent and administrative assistant at the school and a Florida Seminole Indian. “That was the sole purpose. This school was built to save our language.’’

It’s no accident the school is a charter. That’s what gave it the flexibility to offer deep immersion in Seminole culture. It’s no surprise, either, that it’s part of a growing trend of charter schools opening on American Indian reservations across the country.

There are now 31 of them, according to a recent report by the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools. Twelve opened on Bureau of Indian Affairs lands between 2005 and 2010.

Some of the increase is due to a decades-old Congressional moratorium on new schools operated by the federal Bureau of Indian Education, which oversees public schools on American Indian reservations. That meant tribes couldn’t expand existing ones, either.

Charters offered an option.

But much of the growth can be attributed to a desire by American Indians to preserve their fading culture.

“When we were growing up, our grandmas were around,’’ said Cecelia Thomas, a Seminole tribal member and bookkeeper at the school where two of her children attended. “Our uncles were around. Our mom and dad were around. We all lived on the same street or in the same little house. We just seemed to be a tighter-knit family.’’

Customs and language were passed down, from generation to generation. But even Thomas, 45, has lost some of those connections. Like a lot of parents her age on the reservation, she can’t speak her native tongue fluently so she can’t teach it to her children.

Before the charter school, she said, “our language was dying.”

Pemayetv Emahakv (pronounced Pema-yetta Emma-ha-ga) has become a critical and spiritual link between the community’s past and the future.

Here, 250 students starting in kindergarten study the ACE (Ah-Chee), the Creek alphabet, for at least an hour a day, as they learn to speak the language of their forefathers. Most of the children (205) are Seminole Indians. The rest are a mix from other tribes, step-children of tribal members and children of school staff.

Culture lessons include boys and girls learning the art of sewing, where they craft beaded jewelry and colorful Indian dolls. Another class focuses on Florida Seminoles and their part in state history.

Outside, chickees dot the lush 10-acre campus. A super-sized hut at the back of the school has holes in its thatched roof, made of palm fronds, for cooking. Tribal custom allows only girls to cook. Boys do wood carving. Smaller chickees front a large garden where students grow squash, tomatoes, beans, pumpkins and other vegetables just as their ancestors did.

Before the school opened in 2006, most of the tribe’s students, like their parents, went to traditional public schools in nearby Okeechobee County. They got a good education, said Principal Brian Greseth, but their parents started to worry about the future. “Modern life was changing things,’’ he said.

At first, tribal leaders tried to augment the district curriculum. The state allowed the Seminole students to stay on the reservation once a week to learn the Indian language in what became known as “Indian School.’’ There also was a push to include other cultural lessons in the district schools.

But the weekly effort wasn’t enough, said Michele Thomas. That’s when the idea for a charter school took root. The community opted for a public elementary school rather than a private one. The tribe has one BIE school in nearby Hendry County.

“We knew we were going to send kids off the reservation (for middle and high school), so we wanted them to be exposed to all the same curriculum and testing,’’ Thomas said. “We wanted the FCAT (the standardized test given to public school students).’’

Charter schools are public schools, but they have their own administrators – not the district – overseeing finances and curriculum. The five-member Seminole tribal council, which represents Florida’s five reservations, serves as the Pemayetv Emahkv school board. The tribe also provides two-thirds of the school’s $5 million annual budget, Greseth said.

When the school opened, organizers expected 80 students; 120 showed up. “We’ve been building ever since,’’ the principal said.

Academic success followed. The elementary school received its first A grade from the state this year, after three consecutive Bs. Three years ago, the community added a middle school, which received its third B this year. And there is talk of a high school, Greseth said.

Despite the continued growth, class sizes have remained small, with about 10 students per teacher and a teacher’s aide.

A good number of the 78-member school staff was hand-picked by Greseth, a former assistant principal and 28-year Okeechobee district employee. He has worked at Pemayetv Emahakv for three years. This year, he hired five teachers’ aides from a pool of 75 applications and five teachers from a pool of 30.

Salaries that average 15 percent more than what nearby districts pay helped attract them. But, like Greseth, they also relished the idea of working in a school that provides laptops for every student and spends $16,000 to $18,000 per pupil.

Parents like the extras, too. And the opportunity to learn Creek from their kids.

“To be recognized as a tribe, you have to have the language,’’ said Rita McCabe, a 41-year-old mother whose two sons attended Pemayetv Emahakv before going on to Okeechobee High School.

Like their mom, they couldn’t wait to leave the reservation and go to the big district school. “But now,” McCabe said, “they see they had it much better here.’’

Dear Ms. Ackermann, Having known Brian Greseth since birth and knowing his folks and family, I am not at all surprised at his being so completely involoved and so very dedicated to this WONDERFUL school. In his so capable hands I know that they will continue to excel. Also, very happy to learn that our American Indians are now able to keep their heritage alive and are teaching their children about how so important family-heritage is being passed along to these precious children. Thank you for your outstanding coverage of this school. Sincerely, Connie McKone

Hi Connie, thanks so much for reading our story and taking the time to respond. Principal Greseth does seem to be in his element. The school staff and the children seem quite content in their surroundings. I’ll look forward to hearing good things about this school.

Sherri

[…] allow kids to interact with peers who are succeeding academically, is also why tribes such as the Florida Seminole have begun embracing charter […]

[…] allow kids to interact with peers who are succeeding academically, is also why tribes such as the Florida Seminole have begun embracing charter […]