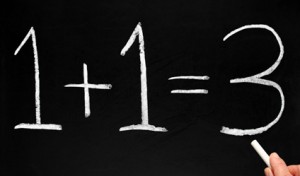

As a stalwart defender of funding for public schools, the Florida Education Association (FEA) brings special expertise to the complex, sometimes arcane ways the state produces its education budget. So its oft-repeated claim this year that scholarships for low-income students increase the total cost of education is presumably a political, not fiscal, calculation.

As a stalwart defender of funding for public schools, the Florida Education Association (FEA) brings special expertise to the complex, sometimes arcane ways the state produces its education budget. So its oft-repeated claim this year that scholarships for low-income students increase the total cost of education is presumably a political, not fiscal, calculation.

Joanne McCall, the vice president for FEA, used a recent op-ed to press the case. “Vouchers,” she wrote, “do not reduce public education costs. Actually, they increase costs, by requiring taxpayers to fund two school systems: one public and one private.”

Two school systems? That description conveniently tracks the union’s combative narrative of public vs. private. But in a state that pays for 1.5 million preK-12 students to attend schools outside their neighborhood public schools, treating all these students as though divide neatly into two separately funded school systems is form of educational sophistry.

First, a little financial history is in order. In 1973, the Legislature created the Florida Education Finance Program (FEFP) in an attempt to remove disparities in funding from one county to another. As the Department of Education describes it, “A key feature of the FEFP is that it bases financial support for education upon the individual student participating in a particular educational program rather than upon the number of teachers or classrooms.”

In other words, the state funds students, not systems. More to the current point, it funds the education option the student chooses even if that conflicts with the district school to which the student is assigned.

If a student chooses a traditional neighborhood school, charter school, magnet program, career academy, virtual school or private school on a McKay scholarship for disabled students, the transaction is direct. The state appropriates funds for that student through the FEFP formula. However, if a student chooses a private school at family expense, stays at home for education, or chooses a tax credit scholarship for low-income students, the state provides no money for that student through the FEFP.

FEA budget analysts understand this formula, which represents basic financial common sense: schools don’t receive money for students they don’t teach. The analysts also know that the options funded directly through the FEFP, such as the International Baccalaureate or charter school or McKay Scholarship, get higher amounts per student. The tax credit scholarship, which has been singled out as increasing the cost of education, actually receives the least.

The scholarship is paid in a different manner than these other options, so its impact on the budget requires two computations rather than one. That complexity has sometimes been used to obfuscate. The scholarships are funded with corporate contributions that receive a dollar-for-dollar tax credit, which means the first computation is the amount of money that is lost to the treasury through this credits. The second computation is the one that puts those losses in perspective, because it involves tracking the dollars that were saved for those scholarship students who otherwise would be attending a traditional public school.

In that computation, the most important factor is the scholarship cost. This year, it is 72 percent of the FEFP average. That translates to $4,880, this year, or about $2,000 less than the state’s per-pupil operational allocation. What’s more, the FEFP represents only about 74 percent of the total local and state money spent on each public school student. So the scholarship this year comes to roughly 53 cents on the public school dollar.

If simple arithmetic isn’t good enough, fear not, five independent research organizations – Florida Tax Watch, Collins Center for Public Policy, the state Office of Program Policy Analysis and Government Accountability, the Office of Economic and Demographic Research and the State Revenue Estimating Conference – have all concluded that the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship saves the state money. The most recent estimate by the Florida Consensus Revenue Estimating Conference projected savings of $57.9 million for the 2012-13 school year.

The two-system line sounds costly, to be sure, but the FEA knows better.