A study released Tuesday finds charter schools as a whole are more cost-effective than district schools.

The study by researchers at the University of Arkansas has produced the first national comparison of the “relative productivity” of the two sectors, drawing on school budgets and student performance data from 27 states and the District of Columbia. The study concludes “charter schools are consistently more productive than traditional public schools” for all of the states it covered.

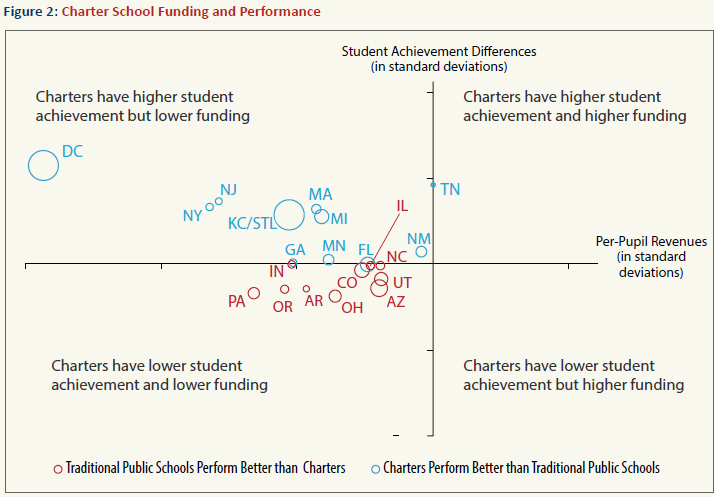

The researchers gauged school productivity by two measures: Cost-effectiveness, based on student scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress per $1,000 in per-pupil revenue, and return on investment, which is based on predictions of students’ future earnings. To score better in either analysis, charters would have to either produce better results for students, receive less funding, or both.

The results may not come as a total surprise to many who follow education policy in Florida, where charter schools generally perform comparably to district-run schools, but do so on smaller budgets.

An earlier study, also by the University of Arkansas’s Department of Education Reform, found charters typically operate on substantially fewer funds than their district-run counterparts.

The newest findings could lend more fuel to the debate over equitable funding for charter schools. The researchers sound a note of caution on that point, pointing out that while more funding per student is associated with better results, the effect of additional funding tends to be small. They do note that “much of the basis for the higher productivity of public charter schools rests on the fact that they receive less funding and therefore are highly disciplined in their use of those education dollars.”

Although an argument can be made that students in public charter schools should be funded at a level that is more equal to the student funding levels in (traditional public schools), and we make that very argument in our revenue study, that argument is grounded in the issue of fairness more so than any empirical certainty that charter schools would continue to be more productive than traditional public schools were all public schools funded equally.

On the measures examined in the study, charters in Washington, D.C. stand out: They outpace traditional public schools by a wider margin on both measures of productivity than those in any of the states. The researchers rank Florida fourth of 22 jurisdictions for cost-effectiveness, and 14 of 21 areas examined for return on investment.

Albert Cheng, a University of Arkansas doctoral fellow and one of the study’s authors, said there are strengths and weaknesses in both measures, one of which is closely tied to student NAEP scores and one that projects further into students’ futures.

“We felt that both would be valuable pieces to include in debates,” he said. “The bottom line is that both have the same result” — a greater bang for the buck in charter schools.

In nearly half the states included in the study, charters serve greater proportions of students who qualify for the federal school lunch program, which indicates they serve more disadvantaged populations. That is not the case in Florida.

Still, the researchers took steps to control for student characteristics. They also note that many of the states where charters do serve disproportionate numbers of students who qualify for free and reduced-price lunches perform relatively well on their productivity measures. As a result, they write: “Any claim that the higher productivity of charters relative to (traditional public schools) is because charters serve a more advantaged population would be undermined.”

And how many charters serve students with special educational needs? Not many. How many provide a bus for students to ride? Again, not many. Those things require money.I could go on and on with examples of how this study is flawed. Oh yeah, how many charters have CEOs who own a yacht and live in a water front mansion (at least one I know of)? They don’t need more money if they have overpaid CEOs, provide few services, and don’t teach students with costly special needs.

Charter schools aren’t provided money for busing. Frankly, I don’t think it should even be centrally run anyway but turned into a voucher parents can use to buy transportation services to any school they want (public, charter or private). But that is another story.

As for special needs, the difference in enrollment between charters and public schools is about 3 points. Basically not that much. Most of the difference seems to come from SD designation (with public schools enrolling far more). SD also happens to be the cheapest to educate.

In a related study, weak, greedy, selfish mountain climbers race to the top of a mountain at the same rate as generous, caring, well trained, athletic mountain climbers. Of course the weak climbers put rocks in the backpacks of the strong climbers. The weak climbers also had the strong climbers carry their backpacks for them, and had the strong climbers push them from behind or pull them up from above. But since the weak climbers put so little effort or care into climbing and still got to the top at the same time, technically, they were more productive than the strong climbers.

Arkansas’s Department of Education Reform was created with money from the Walton Foundation. Since its mission is to advocate for the expansion of charter schools, this research is highly suspect. Has it been peer-reviewed?

Judging schools on a test that is not designed to align with any school’s curriculum, given on one of the 180 or so days a school is in session, is really not a very accurate way of evaluating student learning. The NAEP was not designed to do that, and is, therefore, invalid in association with the conclusion of this biased study.

Oh, and how does the researcher correlate NAEP scores with future earnings? I haven’t read the original study, but this seems to be a giant leap in thinking.

Lisa –

The study has been submitted to a peer-reviewed journal but review and publication take time.

The earnings calculations are not tied to NAEP scores and the projections are based on a method that has been published in other respectable studies such as the one I linked to in the article: https://hanushek.stanford.edu/publications/valuing-teachers-how-much-good-teacher-worth.

The issues you raise are exactly why the researchers used two different measures to gauge productivity.

[…] Patrick Wolf and Albert Cheng’s study on charter school productivity featured in RedefinED […]