Editor’s note: This is the second post in our school choice wish series. See the rest of the line-up here.

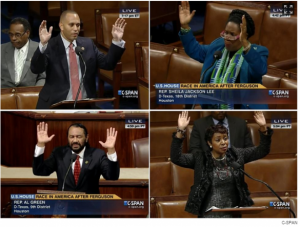

I wish those who are outraged and protesting that “black lives matter” over the two-tiered policing and criminal justice system would connect the dots and express similar outrage over our two-tiered, state-operated, feudal education system. Why do so few similar demonstrations occur, and never with a statewide or national scope, about the outcomes American education provides to families generally, but particularly for African-Americans, when the effects on lives are at least equally devastating?

At the surface, America has these two exemplary 21st Century societal systems that represent the very core of its founding beliefs – equality, justice, and fairness. Criminal law is not race- or class-based as written in statute. Everyone is equal before the law and no one is above it. Public education is free and, since the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education U.S. Supreme Court decision, universally open and equal for all. The double standards that in fact exist are neither explicit nor openly condoned. We have reams of data to document the injustices at the hearts of both systems.

From speeding tickets to drug arrests through convictions to imprisonment, African-Americans (as well as Latinos and poor people of all colors) are disproportionately represented, often grossly so. In the 2011 U.S. Department of Justice’s report, Contacts Between Police and the Public, the Bureau of Justice Statistics found that while white, black, and Hispanic drivers were stopped at similar rates nationwide, black drivers were three times as likely to be searched during a stop as white drivers, and twice as likely as Hispanic drivers. During a more than 20-year period, white secondary students were slightly more likely to have abused an illegal substance within a month than a black student, yet black youths were arrested at twice the rate. Although black Americans make up only 12.7 percent of the U.S. population, they make up 48.2 percent of adults in federal, state, or local prisons and jails.

All Americans accused of a crime have an absolute right to an attorney, but the quality of that defense is inconsistent at best. More than 70 percent of American public defenders’ offices reported extreme or very challenging funding issues in 2012. On average, each public defender handled more than one new case for every day of the year at a rate of $414.55 per case. Given that the poverty rate for both African-Americans and Latinos is about 25 percent compared with 9 percent for whites, many more minorities are affected by this overburdened system.

If convicted, Supreme Court decisions that have made an “inadequate defense” argument nearly impossible to win on appeal only further weaken efforts that advocates make for increasing funding for public defenders. Courts have upheld convictions even when defense counsels have slept during trials, used cocaine and heroin throughout trials, and admitted they had not been prepared on the facts or law of the case.

These “dots” that have stirred outrage connect easily into an education system that falls far short of its promise for equality and justice. As the Alliance for School Choice recently noted, 75 percent of state prison inmates are high school dropouts. This failure feeds the criminal justice system.

We are making slow progress to increase parental choice, but most students remain assigned to schools via ZIP code.

The result is that the typical city-based, African-American student attends a school that has, on average, less than half the community’s proportion of white students (20 percent and 31 percent, respectively, for mid-size and small metros). Black suburban students are on average in schools that are 70 percent nonwhite; in central urban areas, 90 percent nonwhite. In schools that are 81-100 percent black (and Latino), at least 70 percent also live in poverty.

The result is that the typical city-based, African-American student attends a school that has, on average, less than half the community’s proportion of white students (20 percent and 31 percent, respectively, for mid-size and small metros). Black suburban students are on average in schools that are 70 percent nonwhite; in central urban areas, 90 percent nonwhite. In schools that are 81-100 percent black (and Latino), at least 70 percent also live in poverty.

Our union-driven seniority system means that frequently the newest, least experienced teachers are placed in these schools, and rotate out of them quickly. The Black Alliance for Educational Options (BAEO) notes 42 percent of blacks attend under-resourced schools.

Parallel with the inadequate public defense system is the student’s right to a high-quality teacher under the federal No Child Left Behind Act. But with public school teacher tenure and dismissal laws, parents and students have virtually no redress against incompetent or lazy teachers who do not do their jobs. The Vergara ruling in California this summer found that state’s tenure and dismissal law unconstitutional based on evidence that the process was so unwieldy and expensive, only two teachers annually out of 300,000 had been removed for ineffectiveness. Repeated testimony identified many districts that continued to employ ineffective teachers, including Los Angeles Unified that alone had 350 at time of trial. The court found high-minority population schools are disproportionately adversely affected, as often these teachers end up pushed into these schools when other district schools refuse to take them and no other assignment is available.

With these inputs, the academic outputs are not surprising:

- Fewer than one in five black fourth-graders and eighth-graders scored “proficient” or above in either math or English Language arts in 2013

- Blacks rank last among the main racial subgroups for the percentage of students graduating high school in four years; in urban areas, the rate is less than 50 percent

The “dots” are particularly alarming for black males:

- Black males are three times more likely to be suspended or expelled from school than their white peers

- Black males not eligible for free or reduced-price lunch had reading and math scores similar to or lower than those of white males in national public schools who were eligible for free or reduced-price lunch. Furthermore, black males in urban areas without disabilities had reading and math scores, on average, that were lower than those of white males with disabilities.

This data lacks the immediate shock value of a black teen left lying dead in a Midwest street for four hours on a hot summer day. But for all of us who believe “black lives matter,” indeed, all lives matter, we nevertheless ought to be shocked. As a society, we need to be shocked. We need to protest this. We need to demonstrate against this continuing. Perhaps most of all, we need to ask: Why aren’t we?

We have the plentiful evidence, from Washington, D.C., Milwaukee, and elsewhere that parental choice makes a positive difference, especially for blacks, but also for others. When does societal outrage over the damage our ZIP code education system is inflicting rise to the tipping point? While many black groups have come to support parental choice, others like the NAACP still frustratingly do not. In some states, this is making the difference between enacting, expanding, or even saving choice programs from court challenges.

In 2015, I wish that we recommit to judicial and education systems that live up to the founding principles of America, realizing that justice for all families means restoring their ability to access a safe, high-quality education for their children from the broadest possible array of options. With a better education system, we can significantly reduce the numbers of American youth who now seem destined for prison time. Taking meaningful steps to increase parental choice and access to quality educational opportunities, along with fixing the broken structures in our systems, would demonstrate that we truly believe all lives matter.

Peter Hanley is executive director of the American Center for School Choice.

Coming Tuesday: Sharhonda Bossier, vice president, advocacy and engagement, at Education Cities.

What do you want anyone to do? These black students are from middle class families, probably in middle class zip codes. (you don’t provided data on this, a significant omission.)

If the kids are doing poorly, how do we know it’s the teachers’ fault? Do you accuse teachers of discriminating within their classrooms? Maybe those black kids, on average, just aren’t studying hard enough to do better, or there’s some other explanation that’s down to the student’s responsibility for his or her own performance, rather than everyone else.