Editor’s note: This article draws on a symposium hosted by Education Next, which has become the subject of controversy over the journal’s latest cover. Here, we focus on its contents and their implications. –TP

Despite Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s warnings fifty years ago, the number of children born to single family homes increased while the associated disadvantages have grown even stronger.

The connection between single-parent households and poverty has been well known for decades. It was documented in a report by the late Senator on the hardships facing African-American families in the 1960s.

Yet, in the decades that followed, when looking at children’s educational outcomes, “the predictive power of single-parent family structure appears to have increased over time,” according to Kathleen Ziol-Guest, Greg Duncan and Ariel Kalil, co-authors of an article in the latest issue of Education Next.

The authors find that students in single-parent homes receive, on average, nearly two fewer years of schooling. Furthermore, 40 percent of students in two-parent households go on to complete college, but the figure drops to less than 15 percent for students in single-parent households.

The Moynihan Report, released in 1965 during a time of racial segregation and tension, may have focused its attention on the African-American family, but researchers Sara McLanahan and Christopher Jencks find no evidence that single motherhood has different effects on black or white children.

Single parents can still have a positive impact on their children’s education. Zoil-Guest, Duncan and Kalil discovered that, among single mothers, for every 2 years of education of the mother there was a corresponding rise in educational attainment of the children by nearly one additional year. Other studies show that fathers active with their children’s lives decrease childhood delinquency and drug use and can raise their academic achievement.

Combined, mothers and fathers living together with their children leads to “stronger cognitive and non-cognitive skills” for the children as well as an increased likelihood to going to college, earning more money and forming “stable marriages themselves,” according to a study by the left-of-center Brookings Institute.

What can be done to mitigate the academic disadvantages of poverty and single-parent households?

Conservatives want to address the issue by promoting marriage, while liberals advocate for more preschool and childcare services.

Regardless of those proposals, family structure and parental involvement remain strong predictors of a child’s educational future. The fact that this predictive power is growing stronger should be a wake-up call for education reformers and others who believe educational institutions need to help children succeed, regardless of circumstance. Reformers and educators simply can’t wait for the problems associated with poverty and single-parent households to resolve themselves.

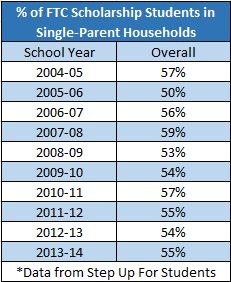

In Florida, 54 percent of students on the tax-credit scholarship program – which offers scholarships for low-income students to attend private schools – come from single-parent households. This figure has remained relatively stable over time, despite the growth of the program and increases in household income eligibility. The program is administered by Step Up For Students, which co-hosts this blog and employs the author of this post.

For a decade now, Florida has centered education policy on improving the quality of education with disadvantaged children in mind. Florida’s tax-credit scholarship program specifically targets low-income children. The correlation between single parenthood and poverty may help explain the high levels of scholarship participation among children of single parents. David Figlio and Cassandra Hart even identified the rise of school choice programs may be spurring improvements in Florida’s public schools.

Florida’s school accountability system also targets disadvantaged students by ensuring the achievement gains for those who struggle academically receive additional weight in A-F school grades. This grading scale has also been attributed as a factor in Florida’s rising student performance.

Nationally, there is evidence that school choice helps students academically. There is also evidence for positive non-cognitive impacts from school choice. The D.C. voucher program boosted high school graduation rates for low-income students. A private voucher program for low-income students in New York City resulted in higher college enrollment rates among African Americans. Additionally, the CREDO charter school study finds strong performance among charter schools serving low-income students, while high-performing charter schools also significantly boost college attedance rates.

Public school choice even improves non-cognitive impacts. A program in the Charlotte-Mecklenburg school district in North Carolina allowed public school students to apply to non-neighborhood schools and researchers discovered the program reduced the risk for criminal activity among male students.

What’s concerning is that many of these improvements have been fairly modest, and gaps clearly remain. It’s still unclear if existing school choice and reform programs are sufficient to resolve the accumulated disadvantages of poverty and living in a single-parent household.

The staggering data accumulated since the Moynihan Report was released 50 years ago reminds us that nationally, these disadvantages appear to have grown stronger with each passing decade. Perhaps more freedom and choices can move us closer to a system in which all children can achieve their potential. Recent evidence suggests we are not there yet.

Education Next will be hosting an event, Single-Parent Families: Revisiting the Moynihan Report 50 Years Later, at 12:15 p.m. Thursday at the Hoover Institution in Washington D.C. The event will be live streamed here and tweeted from the hashtag #MoynihanEN.