One state enrolls 80 percent of its four-year-olds in publicly supported preschool programs, while spending less than $2,300 per student on average. Another spends more than $4,000 per student, but only serves 30 percent of its prekindergarten-aged children.

Which state has made a greater commitment to early learning?

The first would be Florida, where a nearly $400 million Voluntary Prekindergarten program is one of the most widely used forms of school choice, and serves a larger proportion of four-year-olds than its counterparts in any other state but Vermont.

The second is an imaginary state representing the national average in 2014, according to the annual State of Preschool report released earlier this month by the National Institute for Early Education Research.

The scope of Florida’s investment in preschool, mandated by a state constitutional amendment passed in 2002, would exceed the national average since it serves a larger proportion of youngsters. That point isn’t exactly emphasized in the report’s accompanying press release lamenting the level of funding in early learning programs, though it does note a funding increase approved last year is “encouraging.”

The VPK program funds scholarships, which help parents send their children to preschools of their choice. The vast majority of providers are private early learning centers.

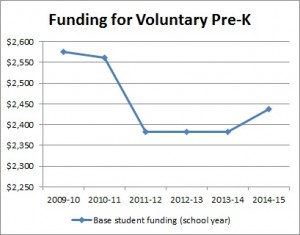

The scholarships are considerably less than per-student funding for K-12 schools, or for other private scholarship programs. While the state mandates fewer hours of instruction for pre-k than it does in elementary schools, some advocates say increased funding could encourage more schools to participate, or to improve their existing programs.

The national report also decries the “quality” of Florida’s preschool offerings. Chester Finn of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute has criticized the report, and its choice of quality measures. He does so again this year.

Aside from the question of whether Uncle Sam should be paying for this, my biggest issue continues to be NIEER’s woeful definition of preschool “quality.” At least eight of their ten “national quality standards” are input-centered, based on credentials, ratios, and such. Yes, they also want states to have “early learning standards,” but these are so nebulous that all fifty-three state programs are said to have “comprehensive” ones in place—the only category among the ten for which every state gets a checkmark. And while the NIEER standards call for site visits at least every five years, they seem to settle for the mere act of visiting, not for rigorous monitoring of whether these programs actually accomplish anything. More like bean counting and box checking.

Florida is trying to implement quality measures that focus on results, rather than “input.” It’s possible to imagine a virtuous cycle where student readiness measures and other increased standards help providers justify requests for more funding, which in turn encourages more, and better, schools to participate. Next year’s funding levels will be decided during the upcoming special legislative session.

Private schools already have one incentive to offer pre-k programs. They can attract younger students who might eventually sign up for kindergarten.

As for public schools, this week during the state Board of Education meeting, Flagler County school superintendent Jacob Oliva said his district expanded pre-K programs at all of its elementary schools for another reason. It wanted to make sure students were ready for elementary school.

“When students are coming in behind, in kindergarten, it’s so hard to catch them up,” he said, “so we’ve made a conscious effort to expand VPK opportunities.”