Students in virtual charter schools fare significantly worse than their peers in traditional schools, and the picture in Florida looks especially bleak, according to a new study by Stanford University’s Center for Research on Education Outcomes (CREDO).

Virtual charters provide flexibility that might benefit some students, the report concludes, but right now, “Academic benefits from online charter schools are currently the exception rather than the rule.”

CREDO is known for its widely cited studies on charter schools. They use a signature method that compares students in one kind of school to “virtual twins” in another, allowing researchers to control for factors like demographics that might influence academic outcomes.

The latest study, released Tuesday, looks at the learning gains of students attending 158 virtual charter schools in 17 states and the District of Columbia over four years.

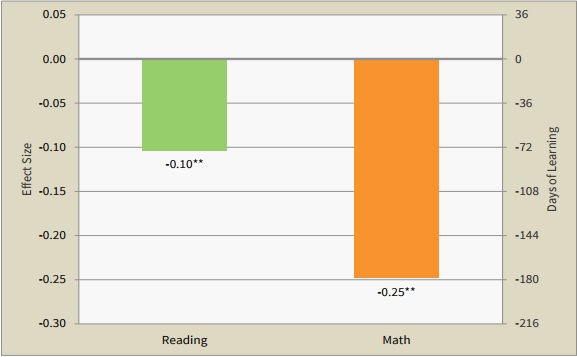

It finds virtual charter school students make significantly slower progress than their peers in traditional, brick-and-mortar schools, losing the statistical equivalent of 72 days’ worth of learning in reading in a typical school, and 180 days in math.

These results, the report says, “leave little doubt attending an online charter school leads to lessened academic growth for the average student.”

The negative effects of virtual charter schools in Florida appear to be almost twice as large as for the overall group in both reading and math. It may be worth noting, however, that the sample of Florida students was the smallest in the study, growing from just six in 2009-10 to 68 in 2012-13. Other states had hundreds, or in some cases thousands, of students included.

The study looked only at full-time virtual charters. It did not include students who took virtual courses part-time, or at charter schools that used blended learning, or at virtual charters that were directly affiliated with bricks-and-mortar campuses.

The virtual-twin statistical approach has limitations. Some online education providers have long contended they attract students who struggle in the schools they leave, the kind of factor that can be hard to fully capture in a statistical model.

The 74 reports at least one well known operator of virtual charter schools has raised this issue in response to the report.

K12 Inc — the nation’s largest operator of online schools — said the study relied on old data from 2012 and that the methodology does not allow for fair comparisons, saying it “cannot accurately match or ‘twin’ students who transfer to online charter schools with those who stay in traditional schools.”

“We understand the academic challenges that face online charter schools, and we have taken vigorous actions over the past two years to meet these challenges with results not reflected in this study,” K12 said in a statement.

K12, which operates multiple virtual charters in Florida, has released a lengthier response here.

The study probes the data in other ways. Another method, which compares the results for students who opted for an online school at some point in their educational career, still finds weak results for virtual charter schools, leading to a grim conclusion:

Current online charter schools may be a good fit for some students, but the evidence suggests that online charters don’t serve very well the relatively atypical set of students that currently attend these schools, much less the general population. Academic benefits from online charter schools are currently the exception rather than the rule. Online charter schools provide a maximum of flexibility for students with schedules which do not fit the TPS setting. This can be a benefit or a liability as flexibility requires discipline and maturity to maintain high standards. Not all families may be equipped to provide the direction needed for online schooling. Online charter schools should ensure their programs are a good fit for their potential students’ particular needs.

The report also suggests state policies matter. Groups like the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools quickly seized on the report to call for policy changes aimed at promoting better quality among online charters. State policies are the subject of an accompanying analysis by the Center on Reinventing Public Education.

Past CREDO studies have looked at the performance of charter schools in general. The differences between its 2009 study and its 2013 follow-up suggest charter schools as a whole are getting better over time.

Therein lies a potential silver lining noted by the researchers: “Taking into consideration the newness of the online sector, it is possible such a pattern might appear here as well given sufficient time.”