On Martin Luther King Day, it is worth remembering the sacrifices people made to advance equity and desegregate public life in America, including our schools. Unfortunately, some activists have begun exploiting the occasion to retell history.

On Martin Luther King Day, it is worth remembering the sacrifices people made to advance equity and desegregate public life in America, including our schools. Unfortunately, some activists have begun exploiting the occasion to retell history.

In the new revisionist stories, modern school choice supporters are close ancestors to the villainous segregationists of the past.

History, of course, is far more complicated. And that’s why it’s worth taking a closer look at some of the scholarship that underpins the misleading narratives about school choice.

Segregationists, it turns out, supported public and private schools alike. And meanwhile, teacher unions in the South ramped up their fights against school vouchers after discovering large numbers of parents used them for reasons other than racial discrimination.

Last year, Duke University historian Nancy MacLean claimed to have uncovered a shocking connection between James Buchanan, a school voucher supporter, and Sen. Harry Byrd’s anti-integration political machine. According to MacLean, Buchanan, a Nobel-winning economist, planted the racist roots of school vouchers by allying with segregationists to pass school vouchers into Virginia law.

A month after MacLean’s book Democracy in Chains was published, the American Federation of Teachers president Randy Weingarten claimed vouchers were the “polite cousin to racial segregation.” Numerous articles began to circulate arguing that school choice and racial segregation were inseparably linked.

But Phil Magness, an economic historian teaching at Berry College, uncovered evidence that McLean and Weingarten’s simple “good vs. evil” narrative is far more complicated.

Magness began digging into MacLean’s scholarship on his blog. He now argues MacLean’s shocking connection between James Buchanan and Sen. Byrd’s segregationist allies was not only based on a typo, but that some segregationists opposed vouchers, too, and teacher unions made them allies.

Magness began digging into MacLean’s scholarship on his blog. He now argues MacLean’s shocking connection between James Buchanan and Sen. Byrd’s segregationist allies was not only based on a typo, but that some segregationists opposed vouchers, too, and teacher unions made them allies.

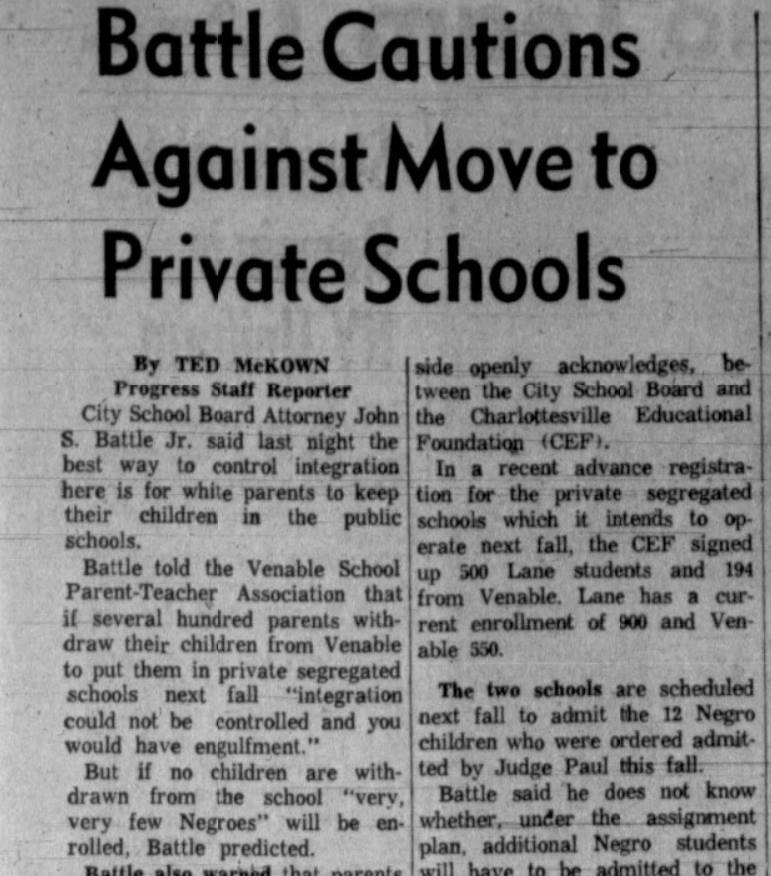

John S. Battle Jr., (whose father was a member of Sen. Byrd’s anti-integration organization) was the attorney for Charlottesville Public Schools and a vocal opponent of vouchers. In March 1959 he argued against school vouchers before the local PTA:

No Negro child is going to force any white child out of his desk at Venable [Elementary School]…But for every white child who vacates his desk there is a great risk that a Negro child will occupy it.

According to Magness’ discovery from the Charlottesville Daily Progress, Battle believed school vouchers would cream the most vocal and involved parents from public schools. With fewer of these parents, school districts wouldn’t be able to effectively resist racial integration.

But as the years passed, parents began using vouchers in unexpected ways. By 1962, the Richmond Times-Dispatch reported many parents were using the vouchers for reasons other than race. The VEA called these non-racial choices “abuses” of the program.

Magness has discovered Virginia Education Association (VEA) decried these choices in a 1964 newsletter:

Certainly the intent was not to subsidize private education generally. The Pupil Scholarship Program is being so greatly abused as to increasingly defeat its original purpose. Of the 12,181 scholarships granted in 1963-64, 10,776 were used in private schools, many of which were integrated, and 1,415 were used in public schools, many of which were integrated. Thus parents are using the grants to send their children to integrated schools which the entire purpose of the legislation was to avoid.

Virginia’s tuition voucher law, as written in 1959, did not explicitly mention race or preference for racial segregation. While some supporters had segregationist intentions, James Buchanan noted in a response to the VEA:

The Virginia Education Association, the organization of public school officials and teachers, early denounced “abuse” of the tuition grant plan. It meant by this expression any use of scholarships except to avoid racial intermixing. Neither the present law nor the regulations of the State Board of Education contain such limitation, although the 1956 law limited the payment of grants to parents who objected to sending their children to integrated public schools.

Buchanan further argued the state Assembly appeared to have little interest in using the vouchers to enforce racial segregation. Legislators did nothing between 1959 and 1964 as more and more families, including more than 400 black students in 1964, used vouchers to enroll in integrated schools.

Magness writes that the VEA went on to lobby the Virginia General Assembly to restrict vouchers to racially segregated schools. In other words, restricting alternatives to unionized public schools trumped the drive to integrate the education system for all children.

Slavery, and its legacies of segregation and right supremacy, were America’s original sin. They defiled all its institutions, including schools. This ugly history might just backfire on those who seek to weaponize it in today’s political battles — especially when they’re fighting against efforts to expand equal opportunity in education.