CLEWISTON, Fla. – It’s hard to think of anywhere in Florida more off the beaten path than the string of blue-collar towns on the rim of Lake Okeechobee. They’re snugged between the grassy, 30-foot-high dike that corrals America’s second-biggest lake, and a 450,000-acre sea of sugar cane that rolls south towards the Everglades. This is not palmy, beachy Florida. This is burning fields and smoking-sugar-mills Florida.

This is also school choice Florida.

The half-dozen towns that ring Lake Okeechobee are home to 10 private schools that serve more than 600 students using school choice scholarships. Four charter schools in the area serve another 600.

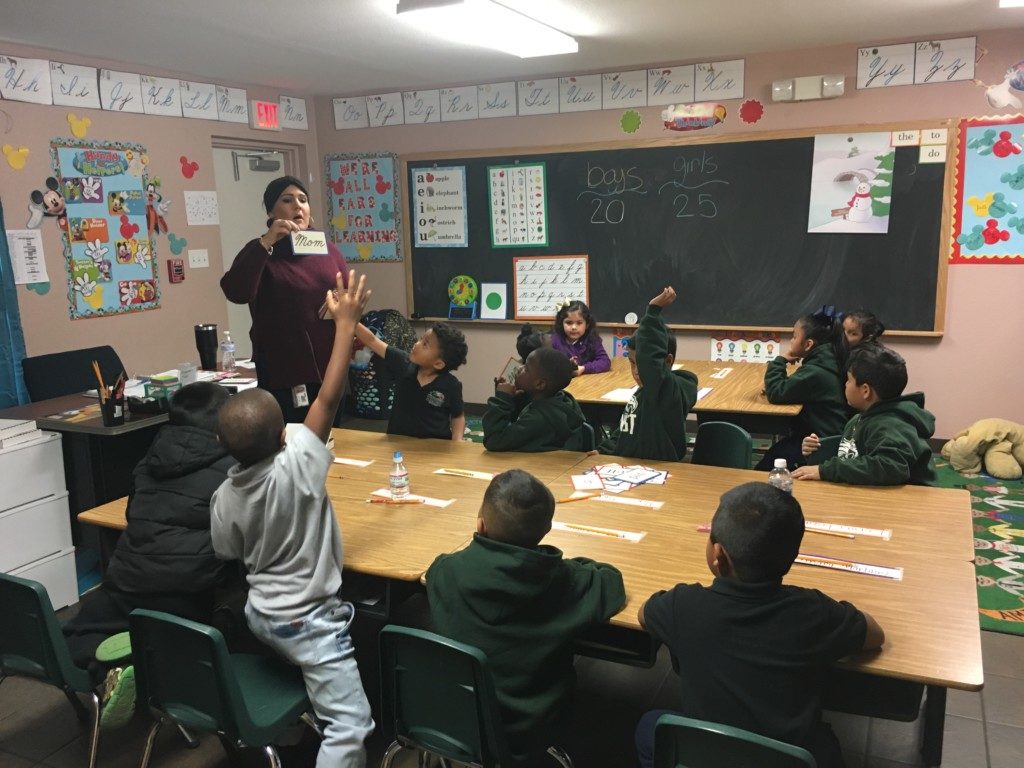

Harvest Academy Christian School in Clewiston, a town too small for a Starbucks, is one of these schools. It opened nine years ago with 12 students. Now it has 120. About 90 use the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship for lower-income students.* Five use McKay Scholarships for students with disabilities.

“I think it’s the best thing that could have happened,” said Sanjuanita Morales, 29, a stay-at-home mom whose three children attend Harvest Academy with tax credit scholarships. “There’s a lot of people that ask about the school and the scholarships and they say, ‘Oh that’s really cool you have options.’ “

The choice schools here are myth chippers. There’s the myth that school choice can’t work in rural areas because there are too many hurdles – including too few students – to make non-district schools viable. Then there’s the myth that rural school districts, often their area’s biggest employers, are especially hostile to choice because they need to keep themselves viable.

Both myths solidified during last year’s confirmation hearings for Betsy DeVos. Both continue to endure in stories like this, this and this. Yet both seem at odds with what’s happening in Florida, which has one of America’s most diverse educational ecosystems.

School choice war? Not here.

Thirty Florida counties are defined as rural, and this year they’re home to more than 80 scholarship-accepting private schools (like this one). Together, those schools are serving 3,828 tax credit students, 999 McKay students and 287 students using Gardiner Scholarships, an education savings account for students with special needs.* Many also serve students using Florida’s pre-K voucher.

Three of those counties abut Lake Okeechobee.

Hendry County, home to Clewiston, has 39,000 residents scattered over 1,190 square miles. If Hendry were a state, its population density would rank near Nevada’s. Okeechobee County on the north end of the lake is a tad less remote (on par with Colorado); Glades County on the west, two tads more (think New Mexico). The east end of the lake rests in Palm Beach County, but Pahokee and Belle Glade are 40 miles, and a galaxy, from the glitz of West Palm Beach.

As for the other myth: Listen to Jesse Windham, principal of Harvest Academy.

“Everyone thinks it’s a war,” he said about school choice. “It’s not here.”

Windham is a former teacher and coach at Clewiston High School, a public school, and carries the solid build of a former college linebacker. The relationship between his school and the Hendry County School District, he said, is cordial and complementary. Two Harvest Academy students play for the Clewiston High football team. The high school hosts its baccalaureate at the church affiliated with the private school. In years past, the district asked Harvest Academy to participate in its spelling bee.

About half the students at Harvest Academy are Hispanic. About a quarter are black. Some of them struggled in district schools. But fully half will enroll or re-enroll in the district when it’s time to go to high school, where the academic programs include 10 Advanced Placement classes. “If you’re about choice and empowering,” Windham said, “how can I get mad at that?”

“You have to realize the dynamics of this community,” he continued. “Everybody’s from here. Everybody knows the child is what’s important here.”

“I needed something different”

Clewiston, “America’s Sweetest Town” (pop. 7,155), is headquarters for U.S. Sugar. The mill smoke billowing over roof tops is a constant reminder of what fuels the local economy. So is the Sweet Town Café, the Blu Cane Ale House and the tractor store next to Goodwill. The town has a McDonald’s, a Dunkin’ Donuts and six district schools (including a pre-school). It also has two private schools that accept school choice scholarships.

It’s undeniable that rural schools, district-run or not, face special challenges. But it’s also true that parents, even in rural areas, want options.

Harvest Academy is growing so fast, it’s had to convert church space into classrooms. The cane harvesters, combine drivers and nursery growers who send their kids here appreciate options for the same reasons parents in the city do. They like the small classes and family vibe. They like the faith-based atmosphere (even if the vast majority do not attend the affiliated church). They like Windham’s vision: “Get your foundation here, Scripture wise and academically. Pursue your passion. Then bring it back home.”

Morales, the mother of three, said she had a bad experience in public school when she was a child. She dropped out in 10th grade; her husband, in 11th. Now he cuts cane in 12-hour shifts. When her first-born, Samantha, began struggling with reading in kindergarten, the teacher seemed too overwhelmed to help, Morales said. She feared a repeat.

Harvest Academy teachers offer more 1-on-1 attention, she said. The principal is fully engaged in helping to pinpoint problems and find remedies. For Morales, the result is confidence her kids will do what she and her husband did not: Go to college.

“For my son, I don’t want him to work as much as my husband works,” she said. “Whenever he grows up and gets married, I want him to have time for his kids and his family.”

Patty Meniz has two children at Harvest Academy: Samuel, in kindergarten; and Israel, in second grade. She considered public school, but feared the district might isolate Israel in special-needs classes because he has ADHD. She had more confidence that Harvest Time would be more accommodating.

“I know a couple other parents that kind of were in the same situation, and they felt the same,” said Meniz, who works in a parts warehouse for the sugar industry. “Having a child like mine, I needed something different.”

“A lot of believers here”

Beyond parental demand, publicly available information about the quality of choice schools around Lake Okeechobee is, for now, fairly limited.

Florida law requires students using tax credit scholarships take state-approved standardized tests. It also requires the average annual learning gains of participating schools with at least 30 students tested in consecutive years be reported. Of the 10 participating private schools around Lake Okeechobee, only one has so far met that threshold, and the most recent results shows its students have been losing ground.

As for charter schools in the area, one recently closed after the state deemed it an F school for a third straight year. Of the four remaining, one, an alternative school, did not get a rating, while two earned C’s and one earned a B.

At Harvest Academy, Windham is confident the school has found its niche. It will thrive if it’s successful, he said, and in turn, so will the community.

“That’s what we believe,” he said, “and we have a lot of believers here.”

*The Florida Tax Credit Scholarship and Gardiner Scholarship are administered by nonprofits such as Step Up For Students, which publishes this blog.

Please don’t let anyone mess up the “choice school” that scholarship helps a lot of family like mine that struggle in the public school system, they don’t help the kids as they are suppose to.