Bellwether Education Partners, a national nonprofit focused on changing education and life outcomes for underserved children, has published an interesting new presentation on education in the American South.

Although I now live in a distant and pleasant patch of western cactus, I grew up in the South (Texas). My parents and siblings attended a Southeastern Conference university – Ole Miss, which may not win every game, but has never lost a party. My parents, in fact, were students at Ole Miss when President John F. Kennedy sent in the National Guard to allow for the enrollment of the first African American student.

Color me interested in how things are going in the American South, and nerdy enough to read all 114 slides of the Bellwether presentation.

To this day, people have very different readings on southern history. Mine goes like this: The American South’s pervasive practice of slavery in the antebellum period, followed by a reckless and destructive decision to go to war against the United States followed by a largely botched Reconstruction, left the South as a poor backwater by the mid-20th century.

The industrial revolution took deeper hold in states open to the waves of 19th century immigrants who did not flock to the South at the prospect of becoming sharecroppers. White Southerners held too tenaciously to the past, replacing slavery with sharecropping and Jim Crow. In the process, the world passed them by as they desperately held on to the past.

The South continued to grow more cotton but found itself increasingly being left behind as the economy advanced. A brilliant strategy of non-violent resistance to Jim Crow during the 1950s and 1960s, however, set the stage for social and economic progress in the region.

Obviously, the scars of this difficult history run deep, and the legacy of slavery and racial discrimination remain, including in the K-12 results, as many of the Bellwether slides demonstrate. But the news is not all bad. By the early 1990s, the South as a region had pulled into rough income parity with the rest of the country once controlling for the cost of living.

Education results, however, have yet to catch up.

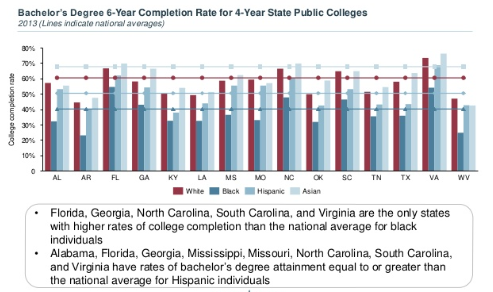

College completion rates for black and Hispanic students in the South are lower overall than national averages. Source: Chronicle of Higher Education

All of which leads to the above chart on six-year college competition rates. It’s difficult to read, but the chart shows college completion rates by ethnic subgroup (white, black, Hispanic and Asian) in the columns and compares those respective rates to the national average (the lines).

To keep from causing squint damage to your eyes, all four Florida subgroups exceed the national average for each subgroup in college completion. Stare long and hard at the chart and you’ll see some other interesting details: the six-year college graduation rate for Florida Hispanic students is higher than the national average for Anglo students. Florida’s black student graduation rate is not only above the national average for black students, it also is above the higher national average for Hispanic students. Florida’s black students have higher graduation rates than white students in Kentucky, Louisiana, Oklahoma, Tennessee and West Virginia.

More progress is needed, but …

Bellwether rightly gives credit to a “first wave” of K-12 reform-minded Democrat governors like Mark White, Bill Clinton and Jim Hunt. This, of course, also is the case with Florida. Shifting partisan allegiances brought in a Republican K-12 reform wave during the 1990s featuring George W. and Jeb Bush.

A new wave is needed, as the region remains a long way from providing globally competitive education.