Editor’s note: Throughout August, redefinED is revisiting stories that shine a light on extraordinary educators. Today’s post, first published in September 2018, features a veteran educator who shares her own life lessons to help the students at her school.

MIAMI – Little Havana is in a hurry.

Long before dawn bathes the palms in soft light, thousands of workers stream from neighborhoods where modest homes are tucked in tight as pastelitos in a Cuban bakery. Ignition. Traction. Acceleration. Past the store fronts with the proud Latin names. Past used car lots studded with American flags. Past the restaurant walk-up windows where smooth, sweet cortaditos pump fuel into true believers.

In the thick of this working-class hum is a faith-based school once harassed by Fidel Castro. He couldn’t kill La Progresiva Presybterian. Neither could the teachers union. Now it’s thriving more than ever.

How fitting that it’s led by a former public school teacher who’s the daughter of exiles.

Melissa Rego grew up four blocks from La Progresiva, the second child of a bank teller and a car mechanic. When she became principal a decade ago, the school with vanilla paint and Cuban roots had 162 students in K-12. Now it has 673 – all with state-backed school choice scholarships for lower-income students.*

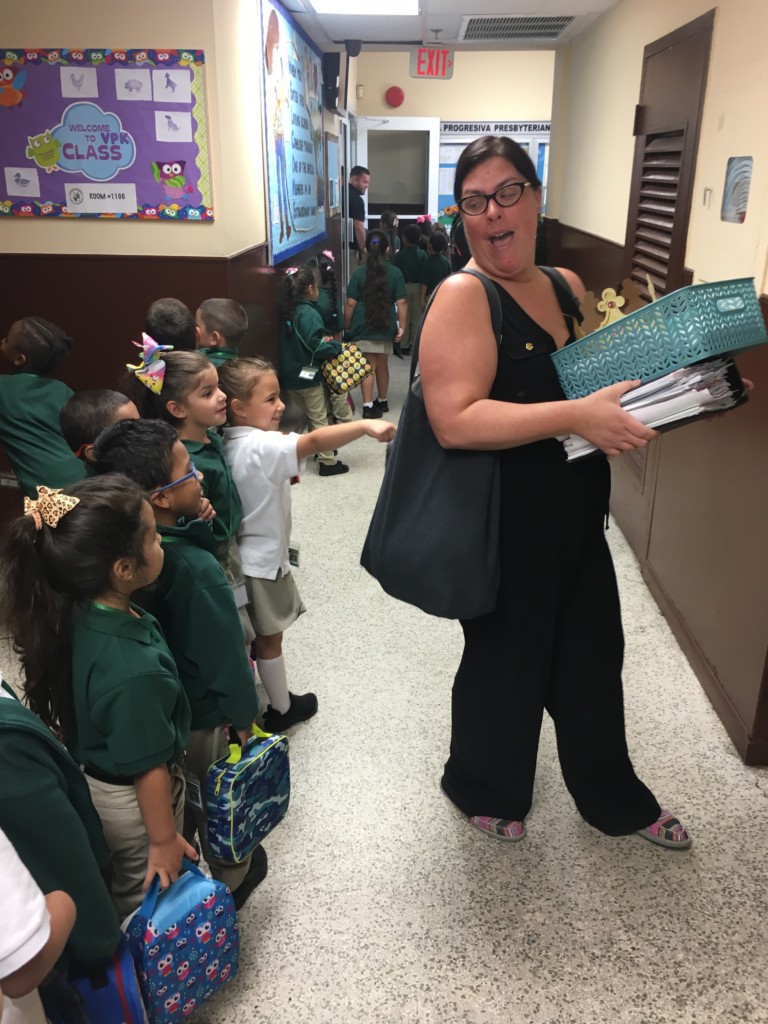

The director who hired Rego told her to do whatever it takes to propel the school to its potential. So the woman with 1,000 facial gestures behind horn-rimmed glasses became Inspirer-in-Chief. Over and over, she reminds the sons and daughters of cooks and waitresses and gas station attendants what Little Havana teaches them every day. They know it in their bones, but still can’t hear it enough from somebody who’s been-there-done-that.

“More than anything, it was speaking life into these kids,” Rego said. “Battling with these kids about the thoughts they have, that they can’t accomplish anything. We told them, ‘You have the ability to do this. We’re going to equip you. You have a future. But you have to grind. You have to work like a dog. Things are not going to fall out of the sky for you.’ ”

Florida is home to arguably the most diverse array of school choice in America. The pluses for students and parents are well established. But choice is helping educators, too. More and more (see here, here, here, here) are able to work in, lead, and even create educational options that are in line with their talents, visions and values. In a world where choice is still “controversial,” they are trail blazers.

Rego, 42, didn’t set out to be one. She graduated from public school in Miami, got a full ride to Miami-Dade College, earned a bachelor’s in health science from the University of Miami. (Later, she earned a master’s in educational leadership from Nova Southeastern.) Her teaching career began 18 years ago. She started as a sub in the Miami-Dade district, working with emotionally disturbed students, then taught four years at a career academy high school. At the invitation of a friend who had become a principal, she headed to a new charter school.

The charter was serving 600 middle school students … in a movie theater. Its intended building wasn’t completed on time, so the school had to wing it.

That it did, successfully, helped Rego understand the power of school choice.

Students, parents and teachers all chose to be there. All worked harder to make their choice work. They were, Rego said, “invested.”

An American missionary founded La Progresiva in Cardenas, Cuba in 1900. It excelled for generations, but the Communist government assumed control of the property in 1961. Ten years later, exiles resurrected the school in Miami.

Rego raised expectations, making college a fundamental goal. The students looking sharp in green, white and khaki uniforms are descendants of Cubans, Nicaraguans, Salvadorans, Dominicans. Seventy percent don’t have parents who attended college. But Rego uses her life as an example of what’s possible. Her students know her mom died of leukemia when she was 13. They know she dug deep to go and grind.

“She’s an amazing human being,” said Solange Robles, a senior who wants to be a doctor. “If you have to talk to her, she’ll talk to you, no matter what. In other schools, you don’t have as much access to teachers and administrators as you do here. In other schools, teachers forget who you are.”

“She’s been a mom to me. I’ve been in her office, crying,” said Leidiana Candelario, a 2018 grad now attending Miami-Dade College. “She said it’s ok to cry, it’s ok to let it out and be vulnerable. Conversations like that I’ll never forget.”

Rego is confidant one minute, goofball the next, commander the next. The school’s Instagram shows her sinking a free throw, granny style, then raising her arms in victory. In class (Rego still teaches Introduction to Government) she’s warm but no-nonsense. As she gooses a discussion about elitism and pluralism, she pumps her fist, scrunches her nose, cocks her head. “Bro,” she says during the follow-up quiz, “it drives me crazy when someone talks during a test.” Snickers fade fast into silence.

It’s easy to find students at La Progresiva who didn’t fare well in public schools. It’s easy to find some who say language barriers slowed them academically and made them prey for bullies. But at La Progresiva, something allows them to rise.

“It goes back to the nurturing,” Rego said. “The kids feel like, ‘There’s somebody in my corner that actually cares about me. I’m not just another face.’ “

What else makes it work? Maybe it’s because it’s smaller. Maybe there’s something about common culture and language that fosters trust. Maybe it’s because La Progresiva can deviate from the script on curriculum, discipline, what’s for lunch. Maybe it’s the emphasis on character. Maybe it’s the constant reminders, from the placards in the front office to weekly chapel, that there’s a shared moral code.

Rego dodges many of the tangles that snare her district counterparts, too. When she took the helm, she hired teachers who shared her vision. Today, La Progresiva has 38 teachers, 40 percent with experience in public schools. Many, like Rego, would make more money in the district.

“But you know what?” she said. “I’m happier here.”

It’s easier to grind when you’re free.

* La Progresiva students use the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship, a school choice scholarship administered by nonprofits like Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog.