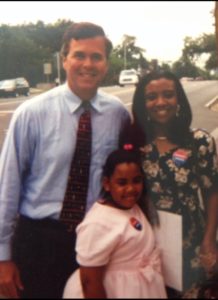

participated in Florida’s Opportunity Scholarship program in early 2000. PHOTO: Michael Spooneybarger

Editor’s note: During this holiday season, redefinED is republishing our best articles of 2019 – those features and commentaries that deserve a second look. This article from Step Up For Students’ director of policy and public affairs Ron Matus was part of our “Education Revolution” series marking the 20th anniversary of the far-reaching K-12 changes Gov. Jeb Bush launched in Florida. Originally published May 30, it spotlights a mom and daughter who participated in Florida’s historic Opportunity Scholarship.

PENSACOLA, Fla. – Tracy James finished the graveyard shift to find her car a casualty of the “voucher wars” – and her 8-year-old, Khaliah, needing another ride to school.

This was 20 years ago, when this Deep South Navy town became the front in the national battle over school choice. In June 1999, Florida’s new governor, Jeb Bush, had signed into law the Opportunity Scholarship, the first, modern, statewide, K-12 private school voucher in America. Khaliah and 56 other students in Pensacola were the first recipients, and now enmeshed in a political clash drawing global attention.

CNN came. A Japanese film crew showed up. So did a member of British Parliament. All wanted to see the “experiment” a Canadian newspaper said “will shape the future of public education in this state and perhaps across the United States.” Tracy and Khaliah were in the thick of it, with Tracy among the most outspoken of an unconventional cast of characters. The single mom with the self-described rebel streak wouldn’t hide her joy at this opportunity for her only child – and refused to cave to anybody who suggested she was being “bamboozled.”

“If you want something better for your children,” she told one paper, “you would do the same thing.”

Not everybody appreciated her resolve.

Tracy walked out of her shift as a phlebotomist to find her car sabotaged, three tires flat as week-old Coke. She called her dad, who said he could take Khaliah to her new school, one Tracy could not afford without the scholarship. The flats left Tracy shocked and ticked – and more determined.

I guess I need tougher skin, she thought. Because we ain’t going back.

Lots of folks know Ruby Bridges. But Khaliah Clanton-Williams? Maybe one day.

The original Opportunity Scholarship students, their parents, and the five private schools that welcomed them have never gotten their due. After an epic legal battle, the Florida Supreme Court ruled the school choice program unconstitutional in 2006, and the decision in Bush v. Holmes seemed to close the chapter. But it didn’t. Many of those whose lives were touched by the scholarship have untold stories, with some still unfolding in ways that attest to the power of that experience.

In one sense, the Opportunity Scholarship was as small-scale as it was short-lived. Students were eligible if their zoned public schools earned two F grades in a 4-year span, and in 1999 only two schools – both in Pensacola – fell into that category. At the same time, most private schools sat it out. Among other restrictions, the law barred them from charging tuition beyond the scholarship amount of $3,400 to $3,800. At its height, the Opportunity Scholarship served 788 students.

And yet, it loomed so large. Florida’s “first voucher” stirred the imagination about what could be with a more pluralistic, parent-driven system of public education. It exposed the festering dissatisfaction many parents had with assigned schools. It enabled and amplified voices that still aren’t heard enough.

Pensacola may be best known for its Blue Angels and sugar-sand beaches. But most of the parents who applied for the school choice scholarships were working-class black women – nursing assistants and bank tellers, cooks and clerks, Head Start workers and homemakers. They had a lot to say about schools in Pensacola’s low-income neighborhoods, and for a few months in 1999, they had the mic.

***

Khaliah’s assigned school was modest red brick, five blocks from her home, named for the district’s first “supervisor of colored schools.” Khaliah would be starting kindergarten, so Tracy stopped to visit. She never got past the front office. “It was a zoo,” she said. “Kids were running around. They were screaming. There was no discipline. There was no structure.”

Nobody with the school acknowledged her, so after a few minutes, Tracy left … for good. She turned to her only option: another district school near her mother’s house, two miles away. Tracy said her mom, a former custodian for the school district, became Khaliah’s guardian so Khaliah could attend. But that school didn’t pan out either.

One day, Tracy watched through a window as kids in Khaliah’s class danced to music blaring from a boom box. She found the teacher in a side office and asked what was going on: “ ‘She said, ‘It’s reading time.’ I said, ‘They’re not reading.’ “ Tracy opened her eyes wide for emphasis.

Khaliah, meanwhile, shy and soft-spoken, was falling behind. “I had a hard time concentrating because it was so loud,” she said. “I’d ask for help and it was like, ‘just a moment.’ But the moment never came.”

Tracy heard about Opportunity Scholarships while working another job as a hotel desk supervisor. Some guests asked her in passing about local schools, and as fate would have it, they were lawyers with the Institute for Justice, the firm that would later help defend the scholarship in court.

Ninety-two students applied for the scholarships, including Khaliah, who had come back to live with Tracy. That exceeded the available seats in the four Catholic schools and one Montessori that opted to participate, so a lottery was held.

Khaliah emerged with a golden ticket.

***

Tracy took her time before deciding on a school. She read up on Catholic schools, talked to friends and co-workers who attended Catholic schools, learned everything she could about Montessori. She was intrigued by the latter – by the mixed-age classrooms, the cultivation of creativity, the curriculum that was so different. In the end, the rebel and her daughter decided they wanted different.

Khaliah attended Montessori School of Pensacola from second through seventh grade, and, in Tracy’s words, “blossomed” in confidence and knowledge. She returned to public school in eighth grade (Tracy wanted her re-acclimated to public school before high school) and graduated from Pensacola High in 2010. For most of the next few years, she worked as a mortgage loan officer. She earned her associate degree in business administration from Pensacola State College in 2018. She’s on track to earn a bachelor’s in human resources management (with honors) in 2020.

Without the Montessori, Khaliah said, much of that would not have happened.

“It made me better,” she said. “I don’t think I would have gone to college. I don’t think I would have gotten my degree. (Montessori) made education more important. It was a higher standard.”

The upside wasn’t just academic. Tracy and Khaliah said nearly everyone in the school embraced Khaliah as family. There were only a few black students before a few more enrolled with the scholarships, but race was not a divide, they said. Khaliah made fast friends. They invited her to sleepovers, to ride horses, to U-pick blueberries. “These things were normal to them, but not to me,” she said.

Montessori co-owner (and head of elementary and middle school) Maria Mitkevicius said increasing diversity was a big reason the school opted into the scholarship program. So was the belief the school shouldn’t be limited to parents of means.

The staff knew the stakes, even if they didn’t know how much things might change. Twenty years after five private schools and 57 kids cracked the door, at least 26 private schools in Escambia County (Pensacola is the county seat) participate in Florida’s K-12 school choice scholarship programs, serving at least 2,163 students. Statewide, 2,000 private schools serve more than 140,000 scholarship students, with thousands more on the way.

“We thought this might change the face of education,” Mitkevicius said. “I guess it did.”

***

The news on Pensacola TV showed 10,000 sign-waving students and parents, marching at a 2016 school choice rally in Tallahassee with Martin Luther King III. As Khaliah watched it again last week, tears fell.

It hurt, she said, to see so many who still don’t have choice or fear their choices could be taken from them. At the same time, how nice to see strength in numbers.

“Back then,” she said, meaning 1999, “it was just us.”

Remembering back then is tough for Tracy too. Some in Pensacola’s black community could not understand why black parents would support anything connected to Jeb Bush. “We were looked on as kind of those people who are being arm twisted by the governor, like you’re letting the Republicans bamboozle you,” said Tracy, now a clinical recruiter for a Pensacola hospital.

It got ugly. Dirty looks. Heated words. The tires. Tracy said some friends and family stopped speaking to her, and she switched jobs because she felt she was being harassed for taking a stand.

But the rebel has no regrets.

“I wanted to try something different, I wanted to be different, I wanted a different opportunity for my daughter,” Tracy said. “From what I saw happening, I wanted to be able to make the choice, myself, of where she’d end up as an adult.”

“I had no idea that it’d turn out to be such a controversial issue,” she continued. “To be thrown into sort of the limelight of a political battle, I had no idea. I had absolutely no idea how important it would be.”

Or how much of a struggle.

“When we went through that program, I was thinking that was kind of the end of an era,” Tracy said. “But it was actually the beginning.”

***

The shy girl who helped pioneer school choice is now a tough-minded mom who needs more.

Khaliah is married to a paper mill machine operator, and their oldest, Kyrian, will begin kindergarten this fall. His zoned school is one of 11 D-rated schools in the district, so like her mom before her, Khaliah looked for alternatives. She applied to three higher-performing district schools through an open enrollment program, but all were full. On a second go-round, Kyrian got into a new elementary north of Pensacola. It’s not ideal. The drive will be up to 45 minutes each way, and Khaliah switched jobs – to drive for Shipt, Lyft and Uber – so she can have flexibility.

Still, she’s worried. Kyrian has special needs – he’s hyperactive, averse to change in routine and undergoing speech therapy – but has not been formally diagnosed with anything. At this time, he wouldn’t qualify for any of Florida’s private school scholarships.

The irony isn’t lost on Tracy and Khaliah. School choice helped them. They helped pave the way for more. Yet 20 years later, there still isn’t enough choice for Kyrian.

The rebel’s daughter said that just means the work isn’t done.

“I’ll continue to fight for my children as my mom fought for me,” Khaliah said. “I’m not taking no as an option.”