Editor’s note: Scroll to the end of this post to watch a portion of Dayspring Academy’s virtual morning assembly, in which assistant principal Jennifer Smith encourages students to “finish this year strong.”

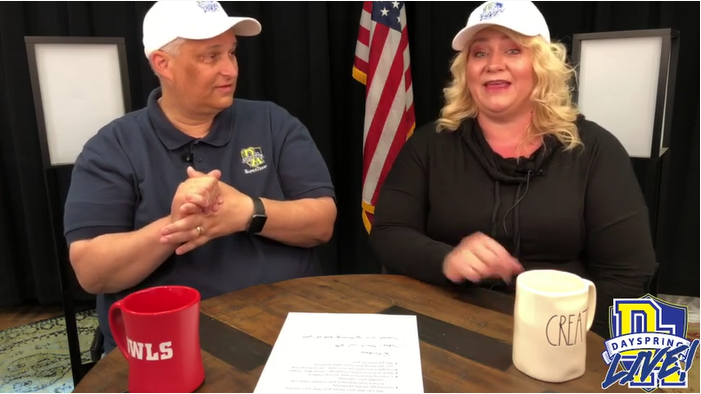

PORT RICHEY, Fla. – The new, online, morning assembly at Dayspring Academy began one day last week with a montage of smiling teachers, set to theme music from “Saturday Night Live.” The secondary school principal and assistant principal kept it laid-back, with their ball caps and coffee mugs. But a few minutes in, they had a serious message for 350 middle and high school students watching on screens at home.

“School” is different now, but it’s still school. Course work needs to be done. Tests are coming up. We need to finish the year strong.

“I want everybody to know this,” principal Tim Greenier said, clasping his hands for emphasis. “We’re not changing the rigor.”

“You need to have this education to be prepared for next year,” he continued. “If we were to just stop now, none of you would be ready for next year. And it would create a challenge. We’re just not prepared to do that.”

Across America, schools are scrambling to figure out what’s doable and appropriate as tens of millions of students switch at a snap to distance learning. Many have decided to go light on academics.

But not all of them.

Dayspring is a PreK-12 charter school with 935 students, 50 miles north of Tampa. When the closures happened, it already had a good bit of digital tech in its tool belt. It quickly filled gaps with devices and connections, then sought to construct an online environment that could approximate the style of learning, built around the Core Knowledge curriculum, that existed on its four brick-and-mortar campuses.

The result: Class is still in session. Dayspring elementary students alone have four, 30-minute core classes every morning, using Schoology and Google Classroom platforms with teachers and classmates. After lunch, they do about two hours of art, dance and other electives. Time for group projects is worked in. So is one-on-one time with teachers. From 3 to 4 p.m., most of them cluster for school clubs, from Legos to ukuleles.

Dayspring students are still being graded and tested. They will still have final exams and report cards. And if attendance is an indicator of engagement, the school is locked in. It averaged 35-45 absences a day before the crisis. It’s averaging six a day now.

“We don’t expect to skip a beat,” said John Legg, a former state senator who co-founded Dayspring 20 years ago with his wife, Suzanne Legg. “We think we’re going to use muscles we haven’t used before and strengthen them. We’re going to be sore. But it’s because we’re developing new muscles.”

At this point in America’s big experiment, Dayspring doesn’t appear to be the norm. State officials in Michigan decided online learning won’t count towards seat-time requirements this year. State officials in Oregon initially told virtual charter schools they had to shut down. It’s not hard, via this database from the Center for Reinventing Public Education, to find districts that have deemed online learning “optional,” or determined their schools won’t be grading students.

On the flip side, there are districts pushing hard (like this one), and charter schools and other schools of choice doing likewise (like these, these, and these). In Rhode Island, Gov. Gina Raimondo told students: “This isn’t vacation. This isn’t time to chill out at home. This is school. Work as hard and as serious as you would as if you were in real school.”

In the 16 years Dayspring has been graded by the state, it’s earned 15 A’s. Forty-eight percent of its students are low-income; 27 percent are students of color. That’s compared to 56 percent and 39 percent for the district it resides in.

Legg is a rare bird. A former chairman of the Senate Education Committee, he was regarded by members of both parties as knowledgeable, thoughtful, even-keeled. He recently earned his doctorate in education, with his dissertation on early college high schools. (Legg is also a member of the board of directors for Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog.)

It doesn’t seem right to hold up any school as a model right now. The challenges are so huge and varied. Nobody has all the answers. But it also doesn’t make sense to ignore schools, like Dayspring, that continue to aim for learning gains.

In Ms. Speer’s third-grade class this week, 25 students dove into colonial America. Ms. Speer had them post their questions about colonists into a program called Nearpod. Within a minute, what looked like Post-it notes mushroomed across the screen. How did the Pilgrims survive on the Mayflower? Why were they only in North America and not any other country? Did people celebrate any holidays such as Christmas, Halloween, Easter, or even their birthdays?

“Guys,” Ms. Speer said through the screen, “your questions are amazing.”

In Ms. Manczak’s class, 20 fourth-graders learned soil types, contrasted physical and chemical weathering, and were reminded “humous” isn’t “hummus.” Ms. Manczak put on a master class in multi-tasking. She deftly called on students, fed them bite-sized bits of knowledge and navigated a new learning platform without breaking a sweat. Some of her students were still adjusting to mics and mutes and chat functions, but disruptions were minimal.

In sixth-grade history, Mr. Marecki used a unit on the Industrial Revolution as fodder for debate about whether teachers, lawyers, military officers or the CEO of Apple should make the most money. One student argued for military officers: they’re willing to give up their lives to protect others. True, said another, but teachers trained them for success. Ah, but “anybody can grow up to be a teacher,” said a third. “Only certain people can, like, become a CEO.”

Mr. Marecki smiled without raising an eyebrow.

Dayspring is making changes as teachers learn what works and what doesn’t. There’s consensus the middle school classes should be longer than 30 minutes. There’s worry the more advanced students aren’t being challenged. There’s a desire to provide more social engagement, but a realization they just don’t know how yet.

“We’re building this plane as we’re flying it,” Legg said.

Not easy for any school right now. But at Dayspring, sitting on the runway wasn’t an option.

My Grandsons attend Dayspring Academy and my wife and I are very impressed with the education they are receiving. Thanks for all you do.

Hi Mr. Savino, thanks so much for taking time out to comment. We’ve heard the same from other parents with children and grandchildren at Dayspring. It was a privilege to have the opportunity to learn a little more about the school, and to tell our readers about it. There are many good lessons for all of us there.