Editor’s note: This commentary was written expressly for redefinED by Matthew H. Lee, a graduate student in education policy at the University of Arkansas; Angela R. Watson, senior research fellow at the Johns Hopkins Institute for Education Policy; and redefinED guest blogger Patrick J. Wolf, distinguished professor of education policy and endowed chair at the University of Arkansas.

“Of all tyrannies, a tyranny sincerely exercised for the good of its victims may be the most oppressive.” — C.S. Lewis

What prompted Cevin Soling, Freedman-Martin fellow in journalism at Harvard’s Kennedy School, to choose this warning as he introduced an event at Harvard earlier this month?

The “tyranny sincerely exercised” is the presumptive ban against homeschooling that Harvard Law professor Elizabeth Bartholet recommends in her recent Arizona Law Review article, “Homeschooling: Parent Rights Absolutism vs. Child Rights to Education & Protection.”

Her proposed ban puts parents “ideologically committed to isolating their children” on trial and assumes their guilt for denying “their children any meaningful education” and subjecting their children to “terrifying physical and emotional abuse.” It shifts the burden of proof to the accused to “demonstrate they would provide a significantly superior education.”

What happened to a presumption of innocence before the law?

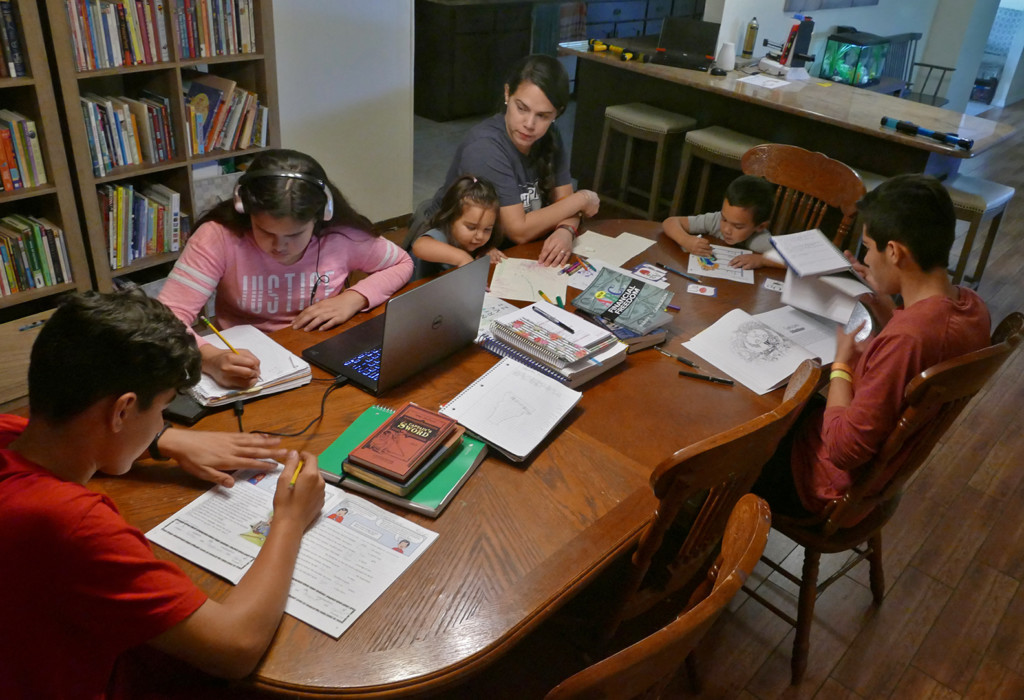

Far from Bartholet’s accusations, homeschooling is not a small, monolithic practice dominated “overwhelmingly” by conservative Christians. At any given time, homeschoolers make up roughly 3 percent of the school-age population, and one study published in the Peabody Journal of Education estimates that as many as 10 percent of all American students are homeschooled at some point during their academic careers.

A 2019 Center for Reinventing Public Education report finds the most rapidly growing homeschooling subgroups are people of color. Another report published in the Peabody Journal of Education noted that “The phenomenon of increasing black home education represents a radical transformative act of self-determination, the likes of which have not been witnessed since the 1960s and ‘70s.”

Meanwhile, National Center for Education Statistics data show that homeschool respondents are more concerned with the “environment of other schools” and “academic instruction” than they “desire to provide religious instruction.”

A presumptive ban against homeschooling denies at least two rights. First, it denies parents the right to govern the education of their child, proclaimed by the US Supreme Court to be their fundamental right in 1923 (Meyer v. Nebraska), 1925 (Pierce v. Society of Sisters), and 2000 (Troxel v. Granville). Second, by giving public officials the authority to conduct home visitations in homeschooling households and to forcibly enroll children in public schools against their parents’ wishes, it denies both parents and children the right to be secure in their persons and homes against unreasonable searches and seizures.

Let’s shift the burden of proof back to homeschooling’s accusers. Can they prove that public schooling delivers better academic results, strengthens democratic values and provides a surer guarantee against abuse than homeschooling?

Homeschooled children demonstrate academic outcomes equal to or better than their public-school counterparts. While we don’t know about academic outcomes for all homeschooled students, a 2010 report by Brian Ray finds that homeschoolers on average score between 15 to 30 percentage points above the national average. As for those who pursue a college education, a review by Gene Gloeckner and Paul Jones indicates that when differences are detected, homeschooled students have higher standardized test scores and college GPAs relative to their public school peers.

Homeschoolers also compare favorably to publicly schooled students on civic and democratic values. Research by Albert Cheng of the University of Arkansas finds homeschooling is associated with more political tolerance relative to public schooling. Indiana University’s Robert Kunzman reports a similar advantage in his 2009 book, “Write These Laws on Your Children: Inside the World of Conservative Christian Homeschooling.”

As for public school students, according to the 2018 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) Civics Assessment, only 24 percent of U.S. eighth-graders perform at or above NAEP “Proficient” on civics.

Finally, even public schools cannot provide an absolute guarantee against abuse. In 2004, the US Department of Education estimated that one in 10 public school students will be sexually assaulted by a public school employee by the time they graduate. While abuse anywhere is unacceptable, a presumptive ban against homeschooling assumes parents are guilty of abusing their children until proven innocent while unrealistically assuming public school personnel are always innocent of such horrible transgressions. Unfortunately, they are not.

In delivering the opinion of the Supreme Court in the 1925 case Pierce v. Society of Sisters, Justice James McReynolds wrote, “The child is not the mere creature of the State; those who nurture him and direct his destiny have the right, coupled with the high duty, to recognize and prepare him for additional obligations.” Homeschooling may be the purest expression of families exercising this right and rising up to meet this high duty.

As courts have ruled repeatedly, when homeschooling is put on trial and given due process, a fair reading of the evidence gives us no choice but to emphatically declare, “Not guilty!”