Nearly five years after taking over operations of Jefferson County’s struggling school system, Somerset Academy, Inc. is preparing to return control to the local school board.

“I’m super proud of how far we’ve come,” said Cory Oliver, who has served as principal of the combined K-12 campus since two district schools were turned over to the South Florida based charter school network. “It’s a completely different school.”

Oliver, whose office sports a Superman theme, has a lot to feel good about.

The percentage of students receiving passing scores on state standardized tests, which once were in single digits, are now between 35 and 45% in most subjects. Disciplinary referrals are down by 80% since the start of the 2020-21 school year. The district, which earned D’s in the two years prior to Somerset’s arrival, has improved a letter grade.

The high school graduation rate rose by almost 20 percentage points this year, though state officials caution that may not be accurate as many students were not required to retake graduation tests due to the coronavirus pandemic. Meanwhile, enrollment, which was a little less than 700 in 2017 and represented only about half of all eligible students who lived in the district, has increased to about 779.

The improvements go beyond academics. Somerset installed a new kitchen and added a culinary arts program and built a recording studio. It renovated the gym and refurbished the weight room. Band members got new instruments and football players no longer had to share shoulder pads.

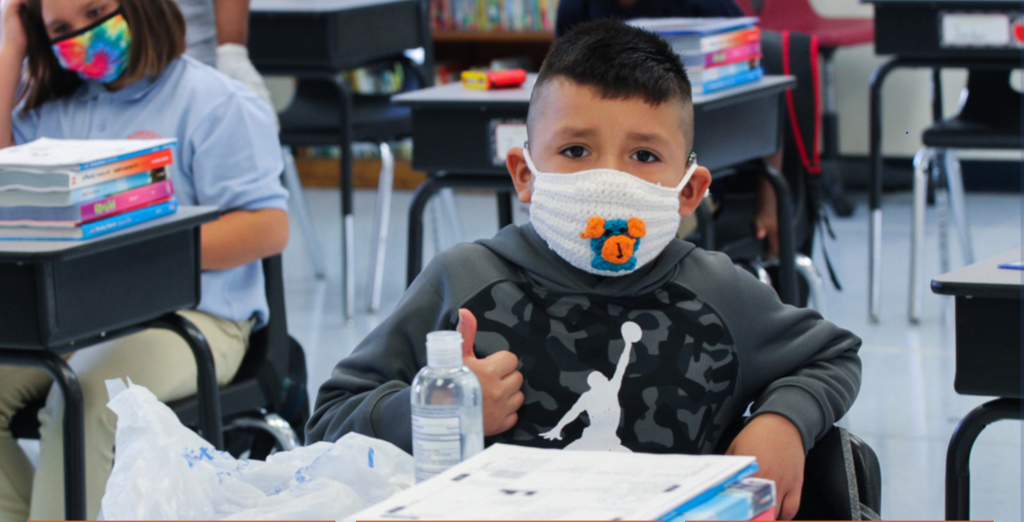

The JROTC program, impressive before Somerset took over, continues to be a shining star. Trophies hidden away in closets are now displayed in trophy cases. Classrooms got technology upgrades. Students got new uniforms.

“It’s like night and day. These kids have been in poverty and living without for so long,” Oliver said. “We want them to see what’s possible and feel like this is home and that they deserve to be here.”

Oliver’s philosophy was reflected in the school’s motto for 2019-20: “Whatever It Takes!” to Somerset officials, it took everything they had to improve what had been the lowest performing schools in the state.

“When we got here, the staff was exhausted and overwhelmed,” Oliver said. “The staff is still exhausted and overwhelmed, but they’re seeing results. They’re seeing what’s possible when they work as a team and know they are going to be supported.”

Residents of Jefferson County, a 637-square-mile area with a population of about 15,000, once were proud of their schools, which were a model for other districts, according to comments Jefferson County School Board member Shirley Washington made at a State Board of Education meeting in 2016.

“We used to be the flying Tigers,” Washington said, referring to the school’s Tiger mascot. “We had other schools come to our county and see what we were doing. We’re going to get it back there. There’s no doubt in my mind.”

But to state officials, the Jefferson County schools looked more like the crash-and-burn Tigers. Florida Department of Education officials came to visit and did not like what they saw.

More than half of the students at Jefferson Middle-High School had been held back two or more times. Just 7% of middle schoolers scored at grade level on 2016 state math assessment. To put that in perspective, 26% of students were performing at grade level in the state’s second-lowest performing district. Enrollment had dwindled for years as more families sent their students to private schools or district schools in neighboring counties. Finances also were a mess.

After rejecting the three turnaround plans that district officials submitted, the Board of Education took an historic vote to make Jefferson County schools the state’s first district run by a charter school provider. The solution mirrored education reform in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina decimated the schools.

Somerset Academy, Inc. won the bid to assume control.

Somerset staff arrived to discover complete disarray: crumbling buildings, graffiti-covered walls, old equipment stacked against classroom walls and no enforcement of discipline.

“It was way worse than we ever imagined,” said Todd German, chairman and treasure of Somerset’s board of directors. “These did not look like places anyone would want to come to learn or come to work.”

School board members pledged to cooperate with Somerset but later said they were “coerced” into accepting the arrangement. The superintendent at the time told WLRN Public Radio that the Department of Education “played in places they shouldn’t have.” Education Commissioner Pam Stewart countered, stating it was “very clear that the Department acted within their authority.”

The charter network fired about half the staff and recruited new teachers. Teacher salaries were raised to $43,800, compared to $36,160 teachers in neighboring Leon County earned. The network hired additional security officers at the schools, where fights had broken out almost daily. One brawl, which occurred just a few months after Somerset came on board, resulted in 15 arrests.

“It was like the wild West,” German recalled, while acknowledging the problems were caused by a small percentage of students. “Cory improved security and put in some zero tolerance policies.”

Oliver said staff from Somerset arrived to find a culture of apathy. Students were allowed to loiter in the halls or outside when they should have been in class.

After the takeover, he said, even the maintenance staff pitched in, alerting administrators when they saw anyone who didn’t belong on campus. Custodians engaged students who looked stressed to make sure they were okay.

“We were de-escalators, not enforcers,” said Oliver, who also hired mental health specialists and started a mentoring program for younger students.

Slowly, the culture began to change. Community members, including the Rev. Pedro McKelvin of Welaunee Missionary Baptist Church, began to support the new leadership. Before the takeover, he said, the district “was on the brink of collapse.”

Christian Steen, a senior, credited Oliver with boosting morale and observed that things had improved significantly.

“The students are more focused in class and now there’s not much skipping,” said Steen when he spoke before a House Education Committee three months after the takeover.

As they enter the last year of their contract, Somerset officials want to prepare to hand the district back to local officials. They already have begun working with a newly elected superintendent to meet that goal. Somerset has offered to let a new principal hired by the school district shadow Oliver before he leaves.

“I have a lot of feelings about leaving Jefferson,” said German, Somerset’s chairman. “I hope we can set (the schools) up to succeed.”