The Educational Opportunity Project at Stanford University released new data recently, covering the years 2007 to 2018. Opportunity Project scholars linked state achievement exams in grades 3-8 across the country to allow comparisons.

Arizona – the state with the nation’s largest charter school sector, a very active open-enrollment market and private choice programs to boot – demonstrated the highest overall level of academic growth among states, for students overall as well as for low-income students.

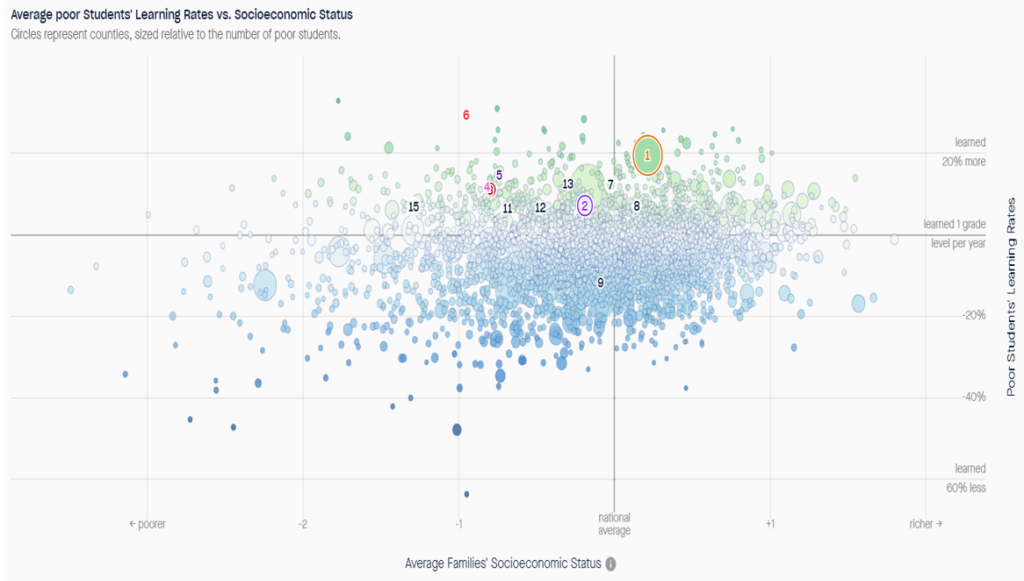

The Opportunity Project’s data explorer has a nifty visualization tool that makes charts like the one above. This one shows the rate of academic growth by county for poor children in counties nationwide.

Each dot is a county. The horizontal dividing line is “learned 1 grade level per year.” As you can see, counties teaching poor children less than one grade level per year (blue dots) easily outnumber those teaching more that one grade level per year (green dots).

Arizona counties are numbered. Maricopa County (1) has the highest rate of academic growth for poor children among large urban counties nationwide, 19.3% above one grade level per year. Mighty Maricopa, however, did not rank first in Arizona. That honor goes to Santa Cruz County (6), on the border of Mexico with a rate 29.3% above the dividing line.

Only one Arizona county, Greenlee (9), has a blue rather than a green shade to its dot. Greenlee, a small rural county in eastern Arizona, has no charter or private schools. The reader can decide for him or herself whether this is coincidental.

Arizona has 15 counties, but Navajo County has missing data for low-income students, so it does not appear in the chart; it does, however, have a healthy green dot for all students. County 15 is not technically a county and is not in Arizona. It’s in Orleans Parish, Louisiana, home of the original portfolio school district.

When Hurricane Katrina destroyed New Orleans, authorities found themselves with no students and little to offer but empty school buildings. Louisiana authorities, wisely, offered the use of those buildings to charter school operators in a request for proposal type fashion.

Most, and then all the schools, became charter schools. Students returned and academic results improved. The rate of academic growth for poor children in the Stanford data, averaging 6.8% above learned one grade level per year, shows admirable progress.

It remains an open question whether anyone will ever meaningfully replicate the New Orleans experiment in a sustained fashion. School boards are easy prey to regulatory capture by incumbent interests such as employee unions and major contractors.

The Arizona experience, fortunately, shows that high levels of academic growth for disadvantaged students can be achieved at a statewide scale and without a natural disaster. Arizona has the nation’s largest charter school sector and private choice programs, which in combination seems to have unlocked a very active system of open-enrollment transfers between district schools.

Arizona districts would die on a hill before being forced to convert to charter schools. Fortunately, there doesn’t seem to be much of a need to do so.